Teaching History with Thinking Maps: A Practical Guide

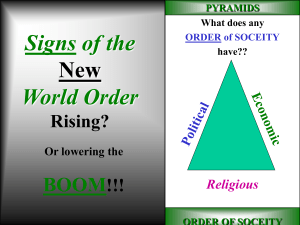

advertisement

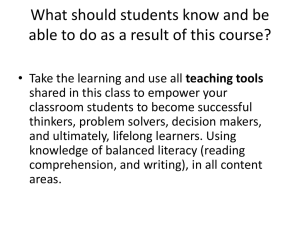

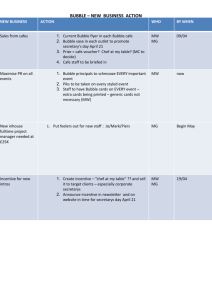

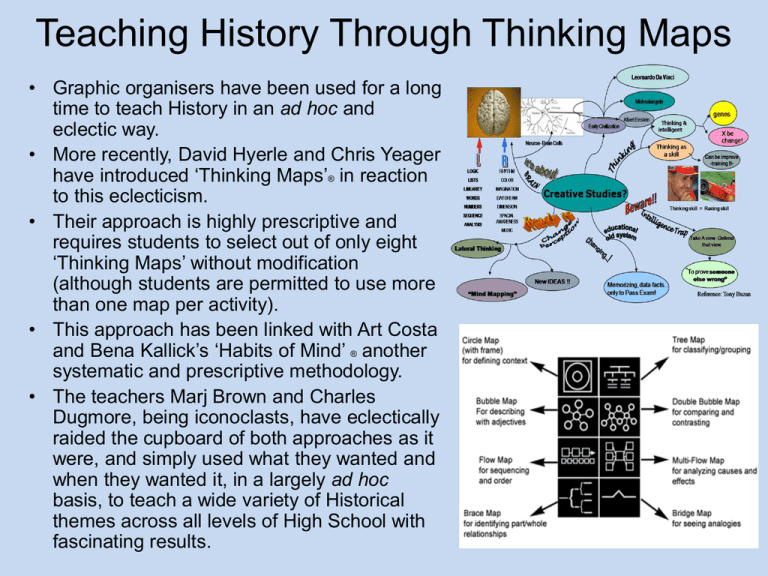

Teaching History Through Thinking Maps • Graphic organisers have been used for a long time to teach History in an ad hoc and eclectic way. • More recently, David Hyerle and Chris Yeager have introduced ‘Thinking Maps’® in reaction to this eclecticism. • Their approach is highly prescriptive and requires students to select out of only eight ‘Thinking Maps’ without modification (although students are permitted to use more than one map per activity). • This approach has been linked with Art Costa and Bena Kallick’s ‘Habits of Mind’ ® another systematic and prescriptive methodology. • The teachers Marj Brown and Charles Dugmore, being iconoclasts, have eclectically raided the cupboard of both approaches as it were, and simply used what they wanted and when they wanted it, in a largely ad hoc basis, to teach a wide variety of Historical themes across all levels of High School with fascinating results. Why use ‘Thinking Maps’ ? • • • • • • The ‘Thinking Maps’ have been used by students to prepare for essays, short tasks in class, as well as to summarise or understand concepts, political stands, cause and effect, the flow of events with examples at each stage, and to compare and contrast people, and groups, or events. This presentation is offered as a way of inspiring possibilities in students to learn by mind mapping History so that it does not become a series of facts to be learned by rote. It also enables students to access a deeper level of learning that makes use of non-textual information to make sense of historical information. Roedean School (SA) has commenced with a process of becoming a registered ‘Thinking School’ and has, over the past few years, adopted Habits of Mind and a range of cognitive approaches including the Thinking Maps as developed by Hyerle and Yeager. The students are becoming familiar with these maps and they were introduced into History lessons in 2014 in a number of lessons. Here are the 8 maps in more detail. The Circle Map – Defining in Context The Bubble Map – Describing Qualities The Double Bubble Map – compare and contrast The Tree Map - Classifying The Brace Map – Part - Whole The Flow Map - Sequencing The Multi-Flow Map – cause and effects The Bridge Map – seeing analogies Using the Circle Map and Double Bubble Map: Indians in South Africa (Grade 8) Using the Circle Map and Double Bubble Map: Indians in South Africa (Grade 8) Lesson Plan Using a ‘Multi-Bubble’ Map to teach Nazi Germany to Grade 9s Lesson Plan Using a ‘Multi-Bubble’ Map to teach Nazi Germany to Grade 9s The Multi-Bubble Map Using a ‘Double Bubble’ Map to teach Civil Society Protests – Lesson Plan Using Thinking Maps/ Graphic organisers to represent an essay: Grade 10 Essay on the ‘Mfecane’ Grade 10 students were given the task of synthesising a range of causes in a critical way. They had to respond to a topic that stated, ‘The Zulu kingdom was just one of several important African states that had an impact on the instability in Southern Africa in the period 1750 to 1835’. Most started by looking at the role of the Zulu as the sole or main factor. They then subjected it to a critique. They then began to unpack all the other factors: • Ndwandwe and Mthethwa • Environmental Factors • Trade with Portuguese at Delagoa Bay • The role of the Boers, Griqua and Kora • The ‘chain reaction’ caused by Mzilikazi’s Ndebele Example One Example Two Example Three Example Four Example Five Findings and Conclusion • Our eclectic approach had given them the confidence to experiment with their own forms of Thinking Maps that produced a better, more accurate version than Hyerle and Yeager’s versions would have produced. • The lesson we take from this experience is while prescription has its place, students are too diverse in their thinking to force them into one of eight ‘channels’ as the Thinking Maps are presented. • History is too complex to be accommodated in the straitjacket of a single Thinking Map. • If we want students to think critically and creatively about their own writing and thinking processes. To promote adaption, modification, creativity and complexity, it necessarily requires a more flexible, eclectic approach in the teaching Thinking Maps than the authors prescribe.