Claim - WCSD Curriculum and Instruction

advertisement

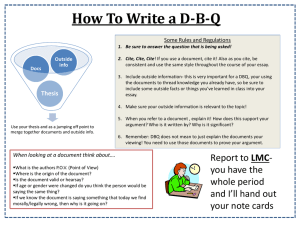

Democratizing the DBQ A System-wide Approach to Historical Thinking for Social Studies and CCSS Presented by: Angela Orr, Nicolette Smith, Katie Anderson, Kristin Campbell PLEASE FILL OUT THE PRE-SURVEY. Introductions Essential Question & Objectives How can we help all students gain important content knowledge through the analysis of primary and secondary sources in document based questions? Objectives: – Develop a shared understanding of the instructional cycle of a DBQ – Identify necessary scaffolds to support students in accessing documents in a DBQ – Evaluate the ways in which DBQs meet the goals of CCSS DBQs & Instructional Shifts Smarter Balanced Testing Claims The Consortium is committed to using evidence-centered design (ECD) in the development of an assessment system. As a part of this design, Smarter Balanced established four “claims” regarding what students should know and be able to do to demonstrate readiness for college and career in the domain of ELA and literacy. • Claim #1 – Students can read closely and analytically to a range of increasingly complex literary and informational texts. • Claim #2 – Students can produce effective and well-grounded writing for a range of purposes and audiences. • Claim #3 – Students can employ effective speaking and listening skills for a range of purposes and audiences. • Claim #4 – Students can engage in research/inquiry to investigate topics, and to analyze, integrate, and present information. Disclaimers • We are providing a “snapshot” experience today. To properly implement a DBQ, you will need at least two weeks of classroom time where the teacher and students are fully engaged in learning experiences. • Expectations: engage like a student (think deeply, write down answers, read quietly, etc.); group work to intentional listening - quiet signal • A DBQ is not: – A packet for students to work on independently. – Something to be done entirely for homework. – A time filler. Primary and Secondary Sources What are primary sources? • Original records from the past recorded by people who were: – Involved in the event – Witnessed the event, OR – Knew the persons involved in the event • They can also be objects (artifacts) or visual evidence. • They give you an idea about what people alive at the time saw or thought about the event. Examples of Primary Sources • Diaries / Letters / Journals • Speeches / Interviews • Audio and Video Recordings • Photographs • Original literary or theatrical works • Original advertisements • Magazine and Newspaper Articles (as long as they are written soon after the fact) What are secondary sources? • Secondary sources are made at a later time. • They include written information by historians or others AFTER an event has taken place. • Although they can be useful and reliable, they cannot reflect what people who lived at the time thought or felt about the event. Examples of secondary sources: • Textbooks, biographies, charts, histories, newspaper report by someone who was not present What is a DBQ? • Collection of primary and secondary sources • Often highlighting multiple perspectives • Used to answer an overarching historical question • Includes writing and discussion Structure of the Binder • Document Based Questions (11) • Teacher Toolkit • Overheads *one per school / make copies of what you will be using The DBQ Project Method Step 1: Engaging the students – The Hook Step 2: Building Context – The Background Essay Step 3: Clarifying the Questions – Defining Key Terms Step 4: Understanding the Documents – Close Analysis Step 5: Grouping the documents – Bucketing Step 6: Writing an Informational or Argumentative Essay Step 7: (optional) Discussion Anatomy of Each DBQ • • • • • • • • • Enhanced Version & Clean Version Teacher Pages and Student Pages Overarching Question Hook Background Essay with Questions Pre-bucketing* & Analysis of Question Documents (4-7) Bucketing Writing (Outline & Writing Samples) WHY HOOK? Weighing Costs & Benefits • Every choice a person (or government or organizations) results in both costs and benefits. • Both costs and benefits can include: The Issue • In 1956, the U.S. Congress passed the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act. The bill created what we now call the Interstate Highway System. (What? What the heck did people do before highways? Was that back in dinosaur time? ) • The interstate system was build over a 35-year period and cost hundreds of billions of dollars (90% of which was federal money and a gas tax). • Complete a cost-benefit analysis of this project. Sorting Activity Costs of the Project Benefits of the Project If you lived in 1956, would you have supported this government project to build interstate highways? Why is it important to look at major projects with a cost-benefit analysis? How can we use this idea to answer our DBQ question: The Great Wall of China: Did the benefits outweigh the costs? Building Background EQ: How can we help ALL students begin the DBQ with basic background knowledge? 1. Beginning, middle, end of unit 2. Necessary vocabulary 3. Maps and/or timelines to orient students to time and place 4. Textbook pages for basic background 5. Breaking down the question together 6. Teacher Pages for Docs (Read through some of these to see if there is background information you would provide to students in a lecture format.) Background Essay • Please read the background essay silently. • Follow along as I read it aloud to you. • Work with your group to answer the Background Essay Questions. Three Tiers of Academic Vocabulary Tier 3: Low frequency, content specific words Tier 2: High frequency, multiple meanings, found across academic texts Tier 1: Vocabulary of everyday language Tier 2 Vocabulary • represent the more sophisticated vocabulary of written, academic texts (used frequently in these types of texts) • the words used by students who have a mature vocabulary • students encounter them less frequently as listeners • The lack of redundancy of Tier 2 in oral language as well as the different meanings of these words depending on context, present challenges to students. Tier 2 & 3 Words • When choosing what Tier Two or Tier Three words to explicitly teach and reinforce with students, consider the following questions you might ask yourself: – Which words are most important to understanding the text we are going to read and/or the concept we are about to study? – Which words do students already have prior knowledge of? – Which words can be figured out using context clues? Vocabulary Scan • Look through the documents in this DBQ. • Make a list of the terms you will need to teach students. – Tier 2 – Tier 3 WHY MODEL? Modeling Document Analysis • • • • • Teaching Historical Thinking Skills Demonstrating the struggle Interrogating documents Wondering/thinking aloud Preparing students for small group analysis Small Group Analysis • Before answering questions: – Source the document – Talk about it (What do you notice? What sticks out to you?) • Work with group to answer questions. • For each document, determine what evidence supports costs? Which supports benefits? • What potential roadblocks would students have with this document? What did we learn from document analysis? • What would you require students to do with each document? • How much class time would building background and document analysis take? • What roadblocks did you identify? How mights we hurdle these? LUNCH WHY BUCKET? Identify the analytical categories that develop your answer to the question. Insert evidence from the documents into each category or bucket. Great Wall of China Buckets • What should we name our buckets? – 2 or 3? • Best way to take evidence from documents for buckets – Context (who, where info is coming from), – quote or paraphrase – followed by (Doc. Letter) According to a letter written by Chao Cuo in 169 BCE, “The Xiongnu live on meat and cheese, wear furs, and possess no house or field.” (Doc. B) WHY WRITE? Writing an Argument THE GREAT WALL OF ANCIENT CHINA: DID THE BENEFITS OUTWEIGH THE COSTS? Definitions for Writing Standard 1 • Argument - “Super Claim”: The overarching idea of an argumentative essay that makes more than one claim. – In some cases, an argument has a single claim, but in sophisticated writing in the secondary grades (8-12 in standards), multiple claims are made. • Claim: a statement that asserts a main point of an argument (a side) • Reasoning: 2 parts – a) the “because” part of an argument and the explanation for why a claim is made; b) the explicit links between the evidence and the claim; the explanation for why a particular piece of evidence is important to the claim and to the argument • Evidence: support for the reasoning in an argument; the “for example” aspect of an argument; the best evidence is text-based, reasonable, and reliable. What claims can you make? • Choose your argument: benefits did/did not outweigh the costs • Go to your buckets. Find related pieces of evidence. When you combine these 2 or 3 pieces of evidence, what kind of assertion/claim can you make to support your overarching argument? Adapted from UNC at Chapel Hill College of Arts and Sciences Writing Center Reasoning Matters • After you introduce evidence into your writing, you must say why and how this evidence supports your argument. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear with reasoning. • We should not assume that our readers already know what we are talking about. The audience can’t read our minds: although they may be familiar with many of the ideas we are discussing, they don’t know what we are trying to do with those ideas unless we indicate it through reasoning. Questions to Develop Reasoning • O.k., I’ve just stated this point, but so what? Why is it interesting? Why should anyone care about this evidence? • What does this information imply? • What are the consequences of thinking this way or looking at a problem this way? (for evidence of a counterclaim) • I’ve just described what something is like or how I see it, but why is it like that? • I’ve just said that something happens-so how does it happen? How does it come to be the way it is? • Why is this information important? Why does it matter? • How is this idea related to my claim? What connections exist between them? Does it support my claim? If so, how does it do that? • Can I give an example to illustrate this point? Adapted from Indiana University Writing Center Reasoning Matters (Example) Weak use of evidence Stronger use of reasoned evidence Today, we are too self-centered. Most families no longer sit down to eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want. Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much anymore as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence. In fact, the evidence shows that most American families no longer eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting selfcenteredness over group identity. Why is this a weak use of evidence? Discuss with the people next to you. Write a Paragraph • For each piece of evidence used in your writing, clearly state your reasoning. • Over-Arching Argument: The benefits of building the Great Wall of China outweighed the costs. • Claim 1: The Great Wall of China was of extreme benefit to the Chinese people living in the border areas. – Evidence: According to a letter written by Chao Cuo in 169 BCE, people living in border areas lived in walled cities “well protected by high walls, deep moats, catapults, and thorns” (Doc. B). – Reasoning: Without walled cities, the Chinese people might have been easily attacked by barbarians like the Xiongnu. Questions to Ask About Writing Assignments • How much? – Always a full essay? – Paragraph? – Outline? • For what purpose? – Culminating assessment of understanding? – Preparation for a discussion? – Formative assessment of writing? Of gathering evidence? Chicken Foot Writing Outline • Introduction – Basic background – Argument with 2 primary claims • Claim Paragraph 1 – Restate claim – 2 pieces of evidence with reasoning linking to the claim • Claim Paragraph 2 – Restate claim – 2 pieces of evidence with reasoning linking to the claim • Conclusion – Although statement/counterclaim (note a piece of evidence from other side), then restate your argument. – Wrap it all up. Elements of a Proficient DBQ Essay Introduction Body Paragraphs Conclusion • • • • • Grabber Background (time, place, story) Restatement of the Questions Definition of Key Terms Super Claim and Roadmap • Claim • Evidence with Citation • Reasoning Linking Evidence to the Claim • Restatement of Super Claim • “Although” Statement (acknowledgement of counterclaim) • Main Evidence & Reasoning that Trumps “Although” Statement • Explanation of why the question is important DBQ Writing Rubric to Modify Writing Samples • Use it to model • Have students assess the sample items • Adding/modifying evidence and reasoning to examples DBQs for Discussion • Consider using DBQs as a jumping off point for great discuss strategies: – Structured Academic Controversy – Socratic Seminar – Philosophical Chairs • Accountable Talk Assessment Alternatives Related Resources • Basil Alignment Project: The Great Wall – Describes the construction of the Great Wall – Includes text-dependent questions – Includes vocabulary ideas – Includes a writing prompt (based on textual evidence) • These two resources together could allow students to use the Great Wall of China as a case study in Chinese culture. Debrief • How do DBQs help students build a coherent body of knowledge on a subject? • How do DBQs help us to slow down and go deep? • How do DBQs help us to shift instruction? • How do DBQs promote historical thinking? • How are we going to implement DBQs into our own classrooms? Professional learning for 6th grade teachers http://www.washoe.k12.nv.us/staff/office-of-staff-development/professional_learning_cafe CCSS: Research Based Discussion Methods (starts January 27 – four Monday afternoons) OR sub day on 2/4 or 3/4 6th grade Social Studies: A Primer (starts February 3 – four Monday afternoons) CCSS: Argumentative Writing (March 11 – sub day) DBQ Follow-Up Course (1/2 day sub on 4/25, morning or afternoon) code: 6DBQApril NNCSS Conference, March 1 POST SURVEY & EVALUATION Please contact us with any questions: Angela: aorr@washoeschools.net Katie: kmanderson@washoeschools.net Nicolette: nsmith@washoeschools.net Kristin: kcampbell@washoeschools.net THANK YOU!