Community-Driven Health Assessment and Improvement

advertisement

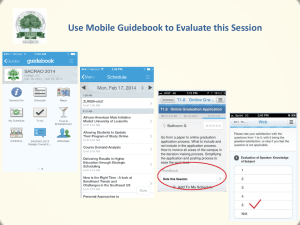

Community-driven health assessment & improvement: A unique model of tribal collaboration in Michigan Shannon Laing, MSWa Kathy Mayo, RNb Open Forum for QI in Public Health November 2013 Memphis, TN aMichigan Public Health Institute bKeweenaw Bay Indian Community Department of Health and Human Services 1 Acknowledgements • Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan (ITCM) • American Indian Health and Family Services • Bay Mills Indian Community • Hannahville Indian Community • Keweenaw Bay Indian Community • Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians • Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa • Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe This work was supported by Cooperative Agreement 5U58DP003004-02 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and an award from the National Network of Public Health Institutes. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC or NNPHI. 2 About the Partnership ITCM Healthy Start 1993: Started receiving HRSA Healthy Start funds and began delivering coordinated tribal maternal-child health services Partnership with MPHI 2005: MPHI began Capacity building working closely with ITCM and Michigan 2008: MPHI Enhancement tribes on health promotion projects partnered with ITCM Healthy Start on 2010: MPHI applied program and staff for CDC Racial and capacity building Ethnic Approaches to Community Health: Communities Organized to Respond & Evaluate (REACH CORE) 3 Healthy Native Communities, Healthy Native Babies (HNCHNB) • CDC REACH CORE grant Sept 2010-Sept 2012 • Required a community health assessment and community action plan • MPHI subcontracted with 7 ITCM Healthy Start sites • Multi-level structure and process – Statewide Consortium – 7 Local consortia 4 MPHI ITCM Communities • Grant management • Reporting • Training • MAPP • Action Planning • Evidence-based strategies • Technical Assistance • Data • Facilitation • Action Planning • Evaluation • Training and technical assistance • Lead the Statewide consortium • Align HNCHNB with other efforts with shared goals • Represent SC on state-level initiatives • Statewide health system action plan • Liaison • Coordinate local consortium • Participate in Statewide Consortium • Engage community members in state and local process • Complete community health assessment • Develop focused Community Action Plans 5 Capacity Building CIRCLE: Community Involvement to Renew Commitment, Leadership, and Effectiveness2 A model of program design and community development for indigenous people 2Chino, M. & DeBruyn, L. (2006) Promoting Commitment Building Relationships Working Together Building Skills 6 Community Capacity & Ownership Building Relationships: • Compensated costs of participating in consortia • Cultural sensitivity and tailoring • Being present in the community • Shared vision Building Skills: • Training community members through all phases • Roles defined by communities • Shared decision-making • Providing tailored, site-specific technical assistance Working Together • Partnership Principles • Plans reviewed and approved by consortium • Using consensus Promoting Commitment • Performance measures • Sharing results and being accountable • Continued relationship and commitment to ITCM Healthy Start and tribal health more broadly 7 …And the Creator gave humans the ability to have visions, to find their purpose or reasons for being here, knowing all along that people sometimes lose their way…We all stray from the Good Path. Then we dream of better times and of a better life, for ourselves and for all who are important to us. And we live to make it real. That is what makes us human...” Thomas Peacock1 Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa 8 Completing MAPP Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP)3 1. Organize for Success 2. Visioning 3. Four Assessments 4. Identify Strategic Issues 5. Formulate Goals and Strategies 6. Action Cycle 3 • Coordinator in each local site to lead MAPP • Training of coordinators and local consortium members • Provided resource materials and TA throughout the process National Association of County & City Health Officials 9 Adapting MAPP • Each site defined “community” and their tribal public health system • Modified or replaced templates and tools • Modified or replaced language, terms, images, and concepts • Adapted phases and components of MAPP to each site’s needs • Applied a maternalchild health lens to the process • Honored experience, cultural values, wisdom 10 Organizing for Success • Formed local consortium with existing groups • Defined own community by geography, population, or characteristics • Tribes decided who to engage and how best to engage them • Focus on only tribal versus including nontribal partners decided by site 11 Visioning • Defined their own community, timeframe, and focus • Large group discussion: brainstorm, check-in, dialogue, and consensus • Facilitated group process to create an asset map Our community will support balance of physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual wellbeing through: • Available healthy, whole, and traditional foods; • Access to safe, clean, drug-free, green space to promote physical activity; • A nurturing and respectful social environment, rooted in tradition, that empowers individuals to fulfill their hopes and dreams; • Providing quality, comprehensive health care that is available to all. 12 MAPP Assessments Grant Year Year 1 Year 2 4Public Assessments Completed Tailoring Community Health Status Assessment (CHSA) Assessed, discussed, and selected short list of indicators for use Community Themes and Strengths Assessment (CTSA) Used a variety of formal and informal methods to gather qualitative information Forces of Change (FOC) Most adaptable and accessible to community members Local Public Health System Assessment (LPHSA) Replaced NPHPSP instrument with tribal-specific tool (PHAB Standards & Measures v. 1.0)4 Health Accreditation Board (2011) 13 Strategic Issues • Evolving discussion about root causes • Compiled and reviewed assessment information in multiple phases • Synthesized and organized all results into diagrams for key topic areas • Facilitated consortia meetings to prioritize issues using ToP Consensus Workshop method 14 15 Goals and Strategies • Relational Worldview Model3 • Training on evidence-based and best practice strategies • Local consortia brainstorm, discuss, and select strategies 3Cross, T. L., Earle, K. A., Echo-Hawk Solie, H., & Manness, K. (2000) 16 Planning for Action Each local community consortium: – Prioritized their strategic issues – Selected 1 - 4 issues to develop a detailed action plan – Completed an action plan with timelines, responsibilities, and outcome measures MPHI supported their efforts by: – Providing templates and resources – Reviewing or drafting SMART objectives – Conducting lit review on strategies and examples – Reviewing plans and providing feedback – Providing site-specific TA as requested 17 Overall Challenges Keeping realistic and feasible timelines Dedicated staff—services came before assessment Presenting technical public health concepts in a way that engages community members Balancing capacity building and empowerment with TA Tailoring TA to each unique community 18 Overall Lessons Learned Priorities of the community must come first Flexibility, adaptability of process, timelines, and methods Communicating key messages continuously, using different words, approaches, and modalities Engaging community members, practitioners, and decision makers 19 Overall Successes Enhanced partnerships at multiple levels Community ownership Increased staff capacity Improved understanding of health issues Increased buy-in for importance of public health strategies Mutual learning: non-Native partners increased understanding of tribal sovereignty and tribal perspectives Good public health practice Sustainability 20 Sustaining Momentum 21 About KBIC • PHAB Beta Test site • Working toward PHAB accreditation • Worked with Tribal Epi Center to strengthen their Community Health Assessment • Worked with MPHI with funding from NNPHI ‘Community Guide’ grant • Continue working to complete a comprehensive Community Health Improvement Plan 22 Our Story 23 Preparing for CHIP • Planning calls to assess capacity and decide on process • Recruitment to enhance the consortium and form an advisory group • Orienting advisory group to key concepts and process • Staff training on evidence based strategies and The Community Guide 24 Review CHA results Identify underlying factors Select priorities 25 Consensus Workshop: Action areas for the CHIP 26 27 • Meeting to review the workbook and steps • Formed action planning teams for each strategic issue • More recruitment of key people • Team meetings to select goals, objectives, strategies • Drafting action plans using workbook 28 Reflections What went well What we will do better • We developed a unified vision of what we wanted to accomplish • Gathered input from different sectors of the community • Collaboration and communication with existing tribal programs and external agencies • Allow staff more time to devote to coordinating this process • Recruit more people to participate in the advisory group 29 Learnings Before you get started… • You need champions • Be inclusive • Plan enough time for staff to participate Keep in mind… • It doesn’t have to be perfect • You can always make changes • Keep it realistic and manageable • Keep moving forward 30 “It is slow and difficult work. Good work is never easy. And it will take the efforts of many more courageous people until the work is complete. Patience is the key...” Thomas Peacock5 Fond du Lac band of Lake Superior Chippewa 31 References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Peacock, T. & Wisuri, M. (2002) The Good Path: Ojibwe learning and activity book for kids. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. National Association of County & City Health Officials. Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships: Achieving Healthier Communities through MAPP. A User’s Handbook. Washington, D.C. Cross, T. L., Earle, K. A., Echo-Hawk Solie, H., & Manness, K. (2000) Promising practices: Cultural strengths and challenges in implementing a system of care model in American Indian communities. Washington, DC: Child, Adolescent and Family Branch/Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Public Health Accreditation Board (2011). Standards and Measures: Version 1.0. Available online: http://www.phaboard.org/accreditation-process/public-healthdepartment-standards-and-measures/ Peacock, T. & Wisuri, M. (2002) The Good Path: Ojibwe learning and activity book for kids. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. 32 Contact Information Shannon Laing, MSW Program Coordinator Center for Healthy Communities Michigan Public Health Institute 2342 Woodlake Drive Okemos, MI 48864 slaing@mphi.org 517.324.7344 www.mphi.org Kathy Mayo, RB Community Health Director Keweenaw Bay Indian Community 33