A new learning theory derived from a phenomenological exploration

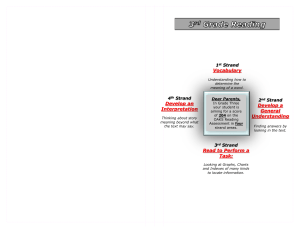

advertisement

A new learning theory derived from a phenomenological exploration of feelings, thinking and learning through practitioner action research. An argument for an additional theory of learning to include emotional and subconscious thought. Dr. Jennifer Anne Hawkins - PhD by research, Manchester Metropolitan University September 2010 Every Child Matters Department for Education and Skills (DfES) 2006 WHO ARE YOU? In d iv id u a l W o rld s 'T h e re e x is ts s u c h g re a t v a ria tio n in th e w a y re a lity is c o n s titu te d , in te rp re te d , a n d e x p la in e d , a n d fo r s o m e it m a y e v e n im p ly th a t th e s p e c ific w a y s w e d o s o a re fu n d a m e n ta lly a rb itra ry : d iffe re n t fic tio n s fo r d iffe re n t fo lk s . B u t th e re is n o th in g a rb itra ry a b o u t th is s itu a tio n a t a ll. A ll th a t is b e in g s a id is th a t w e in te rp re t a n d e x p la in in w a y s th a t a re m o re o r le s s c o n s o n a n t w ith th e p a rtic u la r re a lity w e in h a b it.' (F re e m a n 1 9 9 3 p .1 3 8 ) Why is there a need for an ‘emotional’ learning theory in addition to existing theories? 1. Teachers need to justify ‘emotional’ research with learners in teaching i.e. preparation, curriculum adaptation and assessment of acquisition, motivation and results. 2. Teachers need to justify engendering and allowing for learners’ emotional responses as they teach. 3. In order to promote learning with emotional wellbeing teachers need a theoretical understanding of why learners’ feelings (both physical and mental) are important. Aims of my research • To discover some reasons why students’ labelled as school refusers are disaffected with education and consider their comments and points of view from data gained through home-tutoring them (Inquiry Strand 1: Tutoring twelve school refusers). • To evaluate my own learning and teaching experiences in helping students reengage in education using a reflexive, ethnographic qualitative research method (Inquiry Strand 2: The author’s learning process). • To investigate and compare other teachers’ experiences of learning and teaching through mentoring them (Inquiry Strand 3: Mentoring eight teachers as learners). • To explore the potential to inform and illustrate significant strategies/interventions regarding professional practice and theory without being prescriptive (Inquiry Strand 4: Evaluating a primary school Arts festival: observations of feeling based learning in action). • To disseminate findings, relating material from psychology, education, and counselling literature to teachers and teacher trainers through mentoring, presentation and educational publication (All four inquiry strands). Strand 1 • Participants: 12 school-refusers aged 15 –16 • Question: “Emotional blocks: what do they tell us about the learning process?” (Given that emotional blocks are defined as barriers to learning, which are ‘apparently’ inexplicable.) • Methods: Narrative - phenomenography - participatory action-research - mentoring skills - psychosocial interpretation • Data: Speech transcription, work records with written feeling responses, teaching notes, observations, letters and forms from and reports to the Local Education Authority, reflective summaries, critical points lists and models • Analysis: Thematic GUIDING QUESTION: What is the relationship between feelings, thinking and learning? Graph of tutoring hours per pupil Significant causes of environmental significance were identified from all twelve cases. Themes such as embarrassment, depression (including attempted suicide) and low self-esteem caused by learning difficulties, bullying, confusion caused by inadequate parenting, traumatic events such as illness, bereavement and family break-up. Strand 2 • Participant: The researcher and her learning process • Question: “How do feelings affect my learning and teaching?” • Methods: Narrative – phenomenology - auto-ethnography action research – self-counselling - symbolic models using pictorial symbols • Data: Autobiography from the perspective of a child; an autoethnography from the perspective of an adult based on autobiographical notes and memories, biography and psychological analysis of significant others, reviews and observations on literature, lists of significant and critical points, symbolic modelling using pictorial symbols, researchers reflexive, retrospective and summarised diary • Analysis: Thematic GUIDING QUESTION: What is the relationship between feelings, thinking and learning? Strand 3 • Strand 3 - Mentoring 8 teachers aged 25 – 55 • Question: “How do feelings affect other teachers’ learning and teaching?” • Methods: Narrative - participatory action research mentoring skills - symbolic models using pictorial symbols • Data: Mentoring records, symbolic models, autobiographical writing, participants’ and researcher summaries, and on the spot speech transcription • Analysis: thematic GUIDING QUESTION: What is the relationship between feelings, thinking and learning? Strand 4 • Strand 4 - Evaluating a school arts festival • Question: “How might feeling-responsive environments facilitate the learning of professionals and pupils alike?” • Methods: Narrative - ethnographic- participatory action research - communities of practice - mentoring skills project modelling • Data: Questionnaires, interview notes, project models, evaluation summaries by researcher and participants, observational notes and summaries • Analysis: Thematic in relation to conducive, learning contexts, learning through feelings. GUIDING QUESTION: What is the relationship between feelings, thinking and learning? Thematic Analysis Resilience associated with: absorption (interest, curiosity and fascination), managing distractions (self-knowledge and emotional self-management), noticing (awareness and sensitivity) and perseverance (patience and persistence) Resourcefulness connected with questioning (guessing and sensitivity), making links (open mindedness), imagining (creative construction and awareness) and reasoning (self-confidence, deconstructive and constructive thinking); Reflectiveness linked to planning (self-confidence and awareness of cause and effect), revising (thoughtfulness, patience and determination), distilling (dreaminess, contemplation and meditation) and metalearning (confidence, communication skills, decision making and analysing Reciprocity in relation to interdependence (caring for others and cooperating), collaboration (friendliness, leading and complying), empathy (personal identity, supporting, loving and caring) and listening (including physiognomic perception) and imitation (enthusiasm, admiration and copying). Claxton, G. (2002) Building learning power: helping young people become better learners. Bristol: TLO ‘Meta-learning’ (understanding learning and yourself as a learner) (Claxton, 2002) “An important aspect in developing meta-learning is being given an element of choice. Gilbert points out that teachers should ensure young people have some control, give opportunities for choice and offer young people responsibility. He advises teachers that it is possible, paradoxically, to gain control by giving it (Gilbert, 2002, pp. 94-102). Choice was a key element in much of The Festival work. In Primary School 4’s project, pupils decided on their own project titles. The teacher wrote that the pupils produced “…30 individual creative directions – they decided and developed their own directions for each painting and sculpture”. Emma, a pupil in Primary School 3, explained on her evaluation sheet how the pupils were helped to use their own imaginations. She stated that, “Chloe was very kind and let us have our own choices and not have her choosing everything we do and say. We chose the things we wanted to happen in each scene.”” Hawkins 2010 Findings • Some effects, both physical and mental, of ‘inappropriate’ and ‘appropriate’ emotional learning environments, which either restricted or enabled ‘freedom to learn’, affecting different learners, in different ways (Rogers & Freiberg, 1983). • Discounting emotional and subjective learning contributed towards serious longterm costs to society. In the areas under investigation this tended towards the wastage of school-refusers and teachers as a human resource • There were implications within the research for unacknowledged general educational underachievement and inefficiency due to a lack of knowledge and training. • Learning could be triggered and was influenced through a positive change in environment e.g. Learners benefited from opportunity and encouragement to think in a ‘feeling’ way, exposure to new challenges through ‘feelings’ stimulation, satisfaction in achievement of physical and mental skills and a forgiving ‘positive regard’ teaching approach (Rogers, 1951). • It was clearly evident that ‘successful’ environments might be engineered through the ‘emotional’ skills and understandings of professionals. CONCLUSION: If affective aspects of cognition were theorised, officially recognised, researched, considered and worked with at all levels in the current education system, learning might be more efficiently enabled. “To put it simply – human feelings matter in learning processes, whether we understand and /or agree with them or not. Feelings expressed in this research revealed ‘the remarkable potential of human beings to respond constructively to an ecologically compatible milieu once it is made available’ (Bronfenbrenner, 1979: 7).” Hawkins 2010