Reclaiming Heritage:

Cases of Adult Korean Heritage Language Learners (Pilot Study)

Siwon Lee, Educational Linguistics, University of Pennsylvania (siwlee@gse.upenn.edu)

Background of the Study

Participants

Korean community is one of the most salient ethnic groups in the

United States in terms of collective effort to maintain their

language and culture. There are approximately 1,200 Korean

community language schools in the U.S., most of which are

operated by Korean Christian churches in the form of weekend

schools (Zhou & Kim, 2006). Despite the active community

involvement, these schools have shown low success rates due to

the lack of trained teachers, outdated teaching materials, and

unmotivated students (Lee & Shin, 2008). Even though the ideal

way of maintaining the language is to bring it into the regular

school curriculum, there are currently only five Korean-English

two-way immersion schools in the U.S. (Center for Applied

Linguistics, n.d.). Thus, many Korean immigrants choose to

relearn their mother tongue as adults. The current research is a

multiple case study about two adult 2nd generation Korean

Americans who lost their mother tongue through the course of their

lives but chose to redevelop Korean.

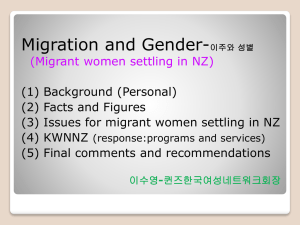

<Student enrollment at Korean community language schools in US>

25000

Name

Angela

Peter

Childhood: Unexplored Ethnicity

Note

Angela is a 33-year-old, 2nd generation Korean

American living in Philadelphia. After she

graduated from university, she started working as

a freelance interior designer and got married. She

has been learning Korean at a non-profit

institution in Philadelphia for almost two years.

Peter is a 30-year-old, 2nd generation Korean

American living in a small Korea town in

Pennsylvania. After graduating from college, he

started working for his family real-estate

business in the town. He has been learning

Korean at the same institution for about three

months.

Theoretical Framework

(1) Ethnic identity as a part of social identity:

“Part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his

knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups)

together with the value and emotional significance attached to that

membership” (Tajfel, 1981, p. 255)

20000

15000

10000

5000

K1-5

K6-8

K9-12

Adults

Research Questions

By following each participant’s path of learning Korean throughout

their lives, the current research aims to address the following

questions:

(1) What factors have affected these Korean Americans’ language

shift toward English?

(2) Why do they strive to relearn Korean as adults?

↓

(3) How does their language use and motivation relate to their

ethnic identity?

Research Methods

The current multiple case study defines a case, or the unit of

analysis, as each individual situated in different learning settings,

and the differences and similarities across cases will shed light on

the overarching theme of the relationship between heritage

language and ethnic identities of Korean Americans.

The study adopted a range of qualitative research methods

including semi-structured interviews and research journals.

Besides informal interaction with the researcher, the participants

were interviewed twice during the two months of data collection

period. The first round of interviews followed the chronological

order of participants’ experiences of learning or using Korean

language throughout their lifetime, and the second interviews were

the follow-ups of the first interviews.

RESEARCH POSTER PRESENTATION DESIGN © 2012

www.PosterPresentations.com

(2) Ethnic identity development models

Marcia Identity

(1980) diffusion

Identity

Moratorium

foreclosure

Phinney Unexamined ethnic

(1989) identity*

teacher actually said to them he have to speak more English in the house,

because he couldn't keep up. So then, they took it (.) very literally, and

then just stopped using Korean. . . My family is a little bit of a rare case of

we just never learned it

Peter: My parents are very educated, and they learned English quickly,

so they um: (.) spoke to us [in English]. . . Actually, I guess it was out of

habit they spoke (.) Korean. >I mean they spoke English.<

Adolescence to Young Adulthood: Identity Conflict

Angela: I didn't wanna know [Korean language] (.) at that time because

I (1.2) when you are in junior high, you don't care about that, or you are

too busy doing something else.

(About her visit to South Korea after graduating from high school) If they

[older Koreans] saw me, and I couldn't speak, and knew that I came from

America, they got really upset. like (.) why don't you know your own,

your own native language. . . And so for a most, a long, a long time, my

life felt like that, if I was (.) around older Koreans, and I tried to speak

Korean, or I didn't understand, there was a lot of negative emotions with

it.

Peter: Dichotomies. It's like I didn't, why are they speaking in Korean. I

didn't really understand them, and I distanced myself from them, and then

(.) but then I wanted to fit in with them because (1.0) um: I am Korean. I

am also Korean, I am not only American.

0

Pre-K

Angela: When my oldest brother was a baby, he spoke Korean. . . he has

Identity

Achievement

Involvement in

Clear sense of

exploring meaning

own ethnicity

of ethnicity**

*One’s identity is either diffuse, which means that he/she has not

given much thought about issues of own ethnicity; or foreclosed,

which means that he/she shows commitment to either one’s own

ethnic group or the dominant group under the influence of parents,

community members, and peers.

**Before the exploring stage, identity crisis stage may be added

when one may become aware of the issues of one’s own ethnicity

due to significant experience but still rejects to explore his/her own

ethnicity (Cross, 1978).

(3) Ethnic identity and language choice

The current study will be based on this postmodernist

understanding of ethnic identity and language (Gilroy, 2000; Hall

1992). Postmodernist epistemologists assert that social identities

are hybrid, dynamic, and complex and that language is a

contingent—not the only essential—feature of one’s ethnicity.

Here, contingency does not mean insignificance. While language

may not be a determining factor of one’s identity, a number of

communities form strong solidarity around their ethnicity and

language regardless of the perceived status of language within the

society, which may account for language maintenance as well as

language shift of minority language speakers.

Adulthood: Exploring Stage

Angela’s Changing Point: I remember feeling regretful after she [my

grandmother] passed away that I didn't I understood generally what she

was saying [during my last visit to her house]. I could tell that she was

saying you know like oh you know good things, but I couldn't, I didn't

know what exactly she was saying. So I regretted (.) not understanding,

and not being able to communicate with her.

Peter’s Changing Point: (About his ten-month stay in South Korea)

Studying [Korean] with all Yonsei students [in Korea], I felt the love for (.)

the country and love for um: you know, just being able to communicate

(.) with native Koreans. And um, it was just: um, yeah, being in that

environment with people from every country. And like (.) it just made

me think of my roots as a Korean American.

Angela’s Motivation and Goals: Definitely learning Korean helps me

understand the culture, and sort of (1.0) like subtleties of culture that

otherwise you wouldn't learn, just from looking at it maybe? Um: (.) but I

think that helps me to identify to also with me and how I think

differently↑. Because (1.0) I think, especially being in a marriage with

somebody that is not of Korean background↑, you see the differences

much more and especially when you start thinking about a family, or even

interacting with each other's families?

. . . I want to at least be able to understand when somebody is talking to

me, even if I can’t say back.

Peter’s Motivation and Goals: My goals (.) are to be, to be fluent in

Korean . . .um: to be a translator for (.) the Korean people so that (.)

they can understand, and other Americans can understand what a Korean

person's saying, and: and to, to be a like a Korean teacher. I want to uh

teach Korean (.) so that they [“other Americans”] can (.) learn how to

communicate.

Conclusions

Ethnic Identity as a Developmental and Social Concept

Ethnic identity is largely influenced by one’s changing

positionality of self within different social contexts , which, in both

cases, ranged from family and school to the macro contexts of

United States and South Korea.

Ethnic Identity in Relation to Language

Language is closely related to how one identifies with his or her

ethnic group.

Angela: Personal level

Angela relates learning Korean

to the process of learning about

Korean culture, i.e. how

Koreans think or how she thinks,

which is also learned through

her personal relationship with

family.

Peter: Community level

Peter relates learning Korean as

a means to learn about Korean

pop culture and to contribute to

the Korean community. He takes

pride in his ethnicity, seeing

many foreigners learning

Korean language.

Acknowledgements and Works Cited

Special thanks to: Professor Sharon Ravitch, Professor Nancy

Hornberger, Professor Yuko Butler, and my great students.

Center for Applied Linguistics. (n.d.). Directory of Two-Way Bilingual

Immersion Programs in the U.S. Retrieved from

http://www.cal.org/jsp/TWI/SchoolListings.jsp

Cross, W (1978). The Thomas and Cross models of psychological

nigrescence: A literature review. Journal of Black Psychology, 4, 13-31.

Gilroy, P. (2000). Between camps. London, UK: Penguin.

Hall, S. (1992). The questions of cultural identity. In S. Hall, D. Held, &

T. McGrew (Eds.), Modernity and its futures (pp. 274-325). Cambridge,

UK: Polity Press.

Lee, J. S., & Shin, S. (2008). Korean heritage language education in the

United States: The current state, opportunities and possibilities.

Heritage Language Journal, 6(2), 1-20.

Marcia, J. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook

of adolescent psychology (pp. 159-187). New York: Wiley.

Phinney, J. (1989). Stages of ethnic identity in minority group adolescents.

Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 34-49

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

Zhou, M., & Kim. S. S. (2006). Community forces, social capital, and

educational achievement: The case of supplementary education in the

Chinese and Korean immigrant communities. Harvard Educational

Review, 76(1), 1-29.

Presenter Information

I am a doctoral student studying Educational Linguistics at

University of Pennsylvania. My research interest is in bilingual

education in the United States as well as in East Asia, the identity

formation of 2nd generation Asian Americans, and curriculum

development for Korean heritage language learners. Currently, I

am teaching Korean at the Society of Young Korean Americans in

Philadelphia. I am also involved in Asia-Pacific Education,

Language Minorities, and Migration (ELMM) network at Penn.