German Hyperinflation of 1923: Causes & Effects

advertisement

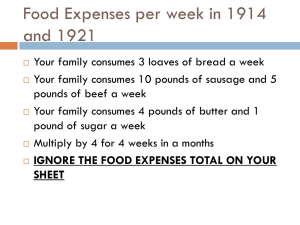

The German Hyperinflation of 1923 Hyperinflation •The drop in confidence caused by the invasion of the Ruhr caused a crisis in Weimar Germany. The government printed money but this which caused inflation. Prices started to rise to match inflation. Very quickly, things got out of control and what is known as hyperinflation set in. •Prices went up quicker than people could spend their money. In 1922, a loaf of bread cost By September 1923, this figure had reached At the peak of hyperinflation, November 1923, a loaf of bread cost 163 marks. 1,500,000 marks. 200,000,000,000 marks. 1914 10 Pfennig, Copper-Nickel This would buy ½ dozen eggs or 2 ½ pounds of potatoes. Bread is 13 Pfennig for a 1 pound loaf. WORLD WAR I STARTS. GERMANY INVADES BELGIUM AND FRANCE 1916 10 Pfennig, Iron Would buy 2 Eggs or 1 ½ Pounds of Potatoes. Bread is 19 Pfennig a loaf. HEAVY FIGHTING ALONG THE WESTERN FRONT RESULTS IN TREMENDOUS CASUALTIES ON BOTH SIDES WITH FEW TERRITORIAL CHANGES. THE BRITISH USE TANKS IN BATTLE FOR THE FIRST TIME. 1918 ½ Mark, Silver Would buy 1 Dozen Eggs, 5 Pounds of Potatoes or a ¼ pound of Meat Bread is 22 Pfennig a loaf. KAISER WILLIAM II ABDICATES. ARMISTICE IS SIGNED. HOSTILITIES CEASE ON NOVEMBER 11, 1918 1919 50 Pfennig, Iron, issued by the City of Sinzig Would buy a pound of Sugar or 4 Pounds of Potatoes Bread is 26 Pfennig a loaf. A HARSH PEACE TREATY THAT INCLUDES HEAVY DEMANDS FOR REPARATIONS IS IMPOSED ON GERMANY 1920 1 Mark, Paper Money Would buy ½ Dozen Eggs or a pound of flour. Bread is 1.20 Mark a loaf. The 1 Mark note, called a "State Loan Currency Note" was not backed by reserves or hard assets. RIOTS TAKE PLACE IN BERLIN AND THE RUHR. 1921 50 Pfennig, aluminum. Would buy 2 Eggs, 1/8 Pound of sugar or ¼ Pound of potatoes. Bread is 1.35 Mark a loaf THE ALLIES OCCUPY DUSSELDORF AND OTHER CITIES BECAUSE OF ALLEGED DEFAULTS IN REPARATION PAYMENTS. 1922 10,000 Mark January 19, 1922 Reichsbanknote In early 1922 10,000 Mark would buy over 250 Pounds of Meat. By the end of the year it would buy only 5 pounds of Meat. In June bread is 3.50 Mark a loaf. When first issued in January of 1922 this note was the highest denomination of circulating currency ever issued by the German government. It would soon become small change. The note is sometimes called the "Vampire Note" . If you look carefully, and have a good imagination, you will see a vampire on the neck of the German worker. This was said to represent the French sucking the blood from Germany through the war reparations. BY AUGUST THE MARK BEGINS A COMPLETE COLLAPSE DUE TO HEAVY REPARATION PAYMENTS. JANUARY 1923 500 Mark, Aluminum Would buy 1 dozen eggs or a pound of flour. Bread is 700 Mark a loaf. This 500 Mark coin was the highest denomination issued for circulation by the German Government. Due to its rapidly decreasing value it rarely circulated. FRENCH AND BELGIAN FORCES OCCUPY THE RUHR AND TAKE OVER MINES AND RAILROADS. MAY 1923 500,000 Mark May 1, 1923 Reichsbanknote Would buy about 40 pounds of meat. Bread is 1200 Mark a loaf. Suitcases, rather than wallets, were used to carry money. JULY 1923 10 Million Mark July 25, 1923 Reichsbanknote Would buy 12 Pounds of Meat or 7 pounds of butter. Bread is 100,000 Mark a loaf. To save printing cost and produce currency faster, the note was printed only on one side. SEPTEMBER 1923 10 Million Mark September 2, 1923, German Railroad Note Would buy about ½ Pound of Meat, 4 eggs or 2 pounds of potatoes. Bread is 2 Million Mark a loaf. The German National Railroad, along with many companies and towns issued their own inflationary currency as the German Government was unable to print money fast enough to keep up with the roaring inflation. As might be expected, these additional issues only further fueled inflation by increasing the money supply. OCTOBER 1923 1 Billion Mark, October 20, 1923 Reichsbanknote Would buy ¾ Pound of Meat, 3 eggs or 1/6 Pound of Butter Bread is 670 Million Mark a loaf. Upon being paid, workers would rush to stores to buy anything they could get, as they knew the prices would be higher in a matter of hours. UPRISINGS, CAUSED IN PART BY THE CONTINUING INFLATION, BREAK OUT THROUGHOUT GERMANY. NOVEMBER 1923 100 Billion Mark, Nov. 3 1923 City of Freital On November 1 100 Billion Mark would buy 3 pounds of meat. Bread is 3 Billion Mark a loaf. On November 15 100 Billion Mark would buy 2 glasses of beer Bread is 80 Billion Mark a loaf. NOVEMBER 1923 • On November 15 a new currency, the Retenmark was introduced. The Retenmark was theoretically backed by all land and industry owned by the government. •One new Retenmark was worth a Trillion of the old Marks. •Prices stabilized under the new currency, however the wealth of most of the nation's citizens had been destroyed. 1924 10 Retenpfennig, aluminum-bronze Would buy 3 Eggs or 2 pounds of Potatoes. Bread is 35 Pfennig a loaf. ADOLF HITLER WRITE "MEIN KAMPF". Effects This table shows what happened to the price of bread in Berlin (prices in marks): December 1918 December 1921 December 1922 January 1923 March 1923 June 1923 July 1923 August 1923 September 1923 October 1923 November 1923 0.5 4 163 250 463 1,465 3,465 69,000 1,512,000 1,743,000,000 201,000,000,000 This is what happened to the price of some other goods: Item 1913 1 egg 0.08 5,000 80,000,000,000 1 kg butter 2.70 26,000 6,000,000,000,000 1 kg beef 1.75 18,800 5,600,000,000,000 12.00 1,000,000 32,000,000,000,000 Pair shoes Summer 1923 November 1923 “Bartering became more and more widespread . . . A haircut cost a couple of eggs . . . A student I knew . . . had sold his gallery ticket . . . at the State Opera for one dollar to an American; he could live on that money quite well for a whole week. The most dramatic changes in Berlin's outward appearance were the masses of beggars in the streets . . . The hard core of the street markets were the petty blackmarketeers ... “ Egon Larsen, a German journalist, remembering in 1976 “In the summer of that inflation year nay grandmother found herself unable to cope. So she asked one of her sons to sell her house. He did so for I don't know how many thousands of millions of marks, The old woman decided to keep the money under her mattress and buy food with it as the need arose - with the result that nothing was left except a pile of worthless paper when she died a few months later.” Egon Larsen, a German journalist, remembering in 1976 “As soon as the factory gates opened and the workers streamed out, pay packets (often in old cigar boxes) in their hands, a kind of relay race began: the wives grabbed the money, rushed to the nearest shops, and bought food before prices went up again. Salaries always lagged behind, the employees on monthly pay were worse off than workers on weekly. People living on fixed incomes sank into deeper and deeper poverty.” Egon Larsen, a German journalist, remembering in 1976 “A familiar sight in the streets were handcarts and laundry baskets full of paper money, being pushed or carried to or from the banks. It sometimes happened that thieves stole the baskets but tipped out the money and left it on the spot. There was dry joke that spread through Germany: papering one's WC with banknotes. Some people made kites for their kids out them.” Egon Larsen, a German journalist, remembering in 1976 “At eleven in the morning a siren sounded. Everybody gathered in the factory yard where a five-ton lorry was drawn up, loaded with paper money. The chief cashier and his assistants climbed up on top. They read out names and just threw out bundles of notes. As soon as you caught one you made a dash for the nearest shop and bought anything that was going.... You very often bought things you did not need. But with those things you could start to barter. You went round and exchanged a pair of shoes for a shirt, or a pair of socks for a sack of potatoes; some cutlery or crockery, for instance, for tea or coffee or butter. And this process was repeated until you eventually ended up with the thing you actually wanted.” Willy Derkow, who was a student at the time, remembering in 1975 “My father began to pay wages largely in goods, mostly foodstuffs. My mother stacked these in the flat where we lived. Livestock, such as chickens, was kept in the bathroom and on the balcony. Flour, fats etc. were bought in bulk as soon as money became available. My mother had to parcel all this food out in rough proportion to the employee's entitlement. Come pay-day the workforce assembled in. the flat in groups for their handouts.” A man whose father owned a small business Some of the experiences are almost amusing: “One fine day I dropped into a cafe to have a coffee. As I went in 1 noticed the price was 5000 marks - just about what I had in my pocket. I sat down, read my paper, drank my coffee, and spent altogether about one hour in the cafe, and then asked for the bill. The waiter duly presented me with a bill for 8000 marks. 'Why 8000 marks?' I asked. The mark had dropped in the meantime, I was told. So I gave the waiter all the money I had, and he was generous enough to leave it at that. “ The memories of a German writer “Two women were carrying a laundry basket filled to the brim with banknotes. Seeing a crowd standing round a shop window, they put down the basket, for a moment to see if there was anything they could buy. When they turned round a few moments later, they found the money there untouched. But the basket was gone. “ The memories of a German writer “A friend of mine was in charge of the office that had to deal with the giving out of ... pensions ...in the district around Frankfurt.... One case which came her way was the widow of a policeman who had died early, leaving four children. She had been awarded three months of her husband's salary (as a pension). My friend worked out the sum with great care ...and sent the papers on as required to Wiesbaden. There they were checked, rubber stamped and sent back to Frankfurt. By the time all this was done, and the money finally paid to the widow, the amount she received would only have paid for three boxes of matches.” A German woman who ran a Christian relief centre for the poor One writer remembers a specific example of the rich getting richer: “A German landowner bought, on credit, a whole herd of valuable cattle. After a certain time he sold one cow from the herd. Because of the depreciation of the mark, the price he got for it was enough to pay off the whole cost of the herd” The memories of a German writer Certain things about the inflation roused people to anger, and this anger led to outbreaks of violence: “At Cologne yesterday outbreaks of looting were a frequent occurrence in spite of the activity of all the available police. Many shops remain unopened and others are barricaded ... Many lorries were held up on their way to market and were looted of potatoes, meat and bread as well as of tobacco and boots.” Evening Standard (a British newspaper) for 13 October 1923 “This financial disaster had profound effects on German society: the working classes were badly hit; wages failed to keep pace with inflation and trade union funds were wiped out. The middle classes and small capitalists lost their savings and many began to look towards the Nazis for improvement. On the other hand landowners and industrialists came out of the crisis well, because they still owned their material wealth - rich farming land, mines and factories. This strengthened the control of big business over the German economy. Some historians have even suggested that the inflation was deliberately engineered by wealthy industrialists with this aim in mind. However, this accusation is impossible to prove one way or the other, though the currency and the economy recovered remarkably quickly.” Norman Lowe, Mastering Modern World History (1982) “We were deceived, too. We used to say, "All of Germany is suffering from inflation." It was not true. There is no game in the whole world in which everyone loses. Someone has to be the winner. The winners in our inflation were big business men in the cities and the "Green Front", -from peasants to the Junkers, in the country. The great losers were the working class and above all the middle class, who had most to lose. How did big business win? Well, from the very beginning they figured their prices in gold value, selling their goods at gold value prices and paying their workers in inflated marks. ... . . You could go to the baker in the morning and buy two rolls for 20 marks; but go there in the afternoon, and the same rolls were 25 marks. The baker didn't know how it happened that the rolls were more expensive in the afternoon. His customers didn't know how it happened. It had somehow to do with the dollar, somehow to do with the stock exchange - and somehow, maybe to do with the Jews.” Erna von Pustau remembering life in Hamburg at the time The impact of hyperinflation was huge : •People were paid by the hour and rushed to pass money to loved ones so that it could be spent before its value meant it was worthless. •People had to shop with wheel barrows full of money •Bartering became common - exchanging something for something else but not accepting money for it. Bartering had been common in Medieval times! •Pensioners on fixed incomes suffered as pensions became worthless. •Restaurants did not print menus as by the time food arrive…the price had gone up! •The poor became even poorer and the winter of 1923 meant that many lived in freezing conditions burning furniture to get some heat. •The very rich suffered least because they had sufficient contacts to get food etc. Most of the very rich were land owners and could produce food on their own estates. •The group that suffered a great deal - proportional to their income - was the middle class. Their hard earned savings disappeared overnight. They did not have the wealth or land to fall back on as the rich had. Many middle class families had to sell family heirlooms to survive. It is not surprising that many of those middle class who suffered in 1923, were to turn to Hitler and the Nazi Party. •Hyperinflation proved to many that the old mark was of no use. Germany needed a new currency. •In September 1923, Germany had a new chancellor, the very able Gustav Stresemann. •He immediately called off passive resistance and ordered the workers in the Ruhr to go back to work. He knew that this was the only common sense approach to a crisis. •The mark was replaced with the Rentenmark which was backed with American gold. •In 1924, the Dawes Plan was announced. This plan, created by Charles Dawes, an American, set realistic targets for German reparation payments. For example, in 1924, the figure was set at £50 million as opposed to the £2 billion of 1922. The American government also loaned Germany $200 million. •This one action stabilised Weimar Germany and over the next five years, 25 million gold marks was invested in Germany. •The economy quickly got back to strength, new factories were built, employment returned and things appeared to be returning to normal. •Stresemann gave Germany a sense of purpose and the problems associated with hyperinflation seemed to disappear. •1924 to 1929 is known as the Golden Age of Weimar. Berlin became the city to go to if you had money, the Nazis were a small, noisy but unimportant party. •Above all, Stresemann gave Germany strong leadership.