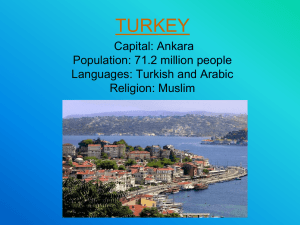

Presentation from Turkey Team

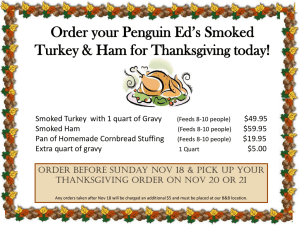

advertisement

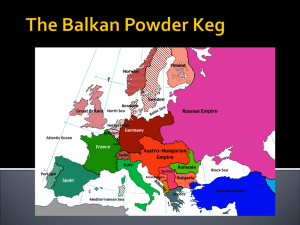

Turkey’s Immigration Policy Profile and Its Reforms. When one thinks of Turkey as a country of immigration, one often sees Turkey as a “new” country of immigration, devoid of any real immigration policy, and one which needs to catch up with Europe and adopt appropriate policies. This is only partly correct. Turkey is historically a country that has received important inflows of immigration, especially from the Balkans, all throughout the 20th century. But, this fact was overshadowed by the large influx of Turkish migrants into Europe starting in the 1960s, which, on the international migration scene, characterized Turkey as a country of emigration.7 Similarly, Turkey had an immigration policy, articulated principally in the Law on Settlement of 1934, foreseeing the immigration of migrants of “Turkish culture or origin”, and the rights to which they would have access as they ettled on Turkish territory.8 Turkey was also among the drafters and first signatories of the Geneva Convention in 1951, practically granting Turkey with an asylum policy.9 However, these existing policies came to a serious crisis by the end of the Cold War, when the sudden qualitative and quantitative change in migration flows in the region rendered existing regulations largely irrelevant and archaic. By the 1990s, a large majority of newcomers coming from Eastern Europe and the Middle East to Turkey were “foreigners”(i. e., “non-Turkish”), and could not be accepted in Turkey under the Law on Settlement. Likewise, most of the asylum seekers were coming from non-European countries (mainly Iran and Iraq) and therefore would not qualify as Convention refugees under the geographical limitation of the Geneva Convention that Turkey maintained.10 Turkey’s Asylum Policy and Practice In the West, Turkey is traditionally known as a country of emigration. Yet, Turkey, like its predecessor the Ottoman Empire, has long been a country of immigration especially for Muslim ethnic groups, ranging from Bosnians to Pomaks and Tatars, as well as Turks from the Balkans and to a lesser extent from the Caucasus and Central Asia. Between 1923 and 1997, more than 1.6 million immigrants came and settled in Turkey.3 Furthermore, after the Nazi takeover in Germany and then during the Second World War, there were many Jews who fled to Turkey and then resettled in Palestine. There were also many who fled the German-occupied Balkans for Turkey and returned to their homelands after the war had ended. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Turkey has also become a country receiving an increasing number of irregular workers and immigrants from Balkan countries and former Soviet Republics as well as Iran, Northern Iraq and Africa. These often include people that overstay their visa and work illegally. Turkey has also been a country of asylum, and is among the original signatories of the 1951 Geneva Convention. However, Turkey is today among a very small number of countries that still maintains a geographical limitation to the agreement’s applicability as defined in Article 1, b(1)(a) of the Convention.4 Accordingly, Turkey does not grant refugee status to asylum seekers coming from outside Europe but has to extend temporary protection, and hence maintains a two-tiered asylum policy. For the first time in 2010, fifty years past the beginning of extensive migration from Turkey to Europe, the number of migrants to Turkey exceeds that of the number of migrants from Turkey. Added to this is an increase in the number of returnees.11 Içduygu, A. 2010. International Migration and Turkey, 2010 OECD SOPEMI Report, Istanbul. Turkey’s former role as a “migrant-sending country” is now supplemented with the role of a “migrant-receiving country”. International migratory movements to Turkey since the end of 1970s have included the migration of transit migrants, irregular migrant workers (mostly from the former USSR and Eastern European countries), asylum-seekers and refugees (from Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq and various other Asian and African countries). The migration of professionals and retirees are also taking place. In sum, a migratory transition has taken place in Turkey in the last decades. Outward migration In 2005, an estimated 3 million Turkish citizens were living in Europe, approximately 105,000 Turkish workers in the Middle East countries and 75,000 workers in the CIS states.Turkish Migrant Stock Abroad in 1995, 2005 and 2010 Some 350,000 Turkish citizens were reported in other countries such as Australia, Canada and the USA. The total number of expatriates equalled 3.3 million (which excludes the number of emigrants from Turkey who were naturalized in receiving countries). This number implies 5% of the nation’s total population living outside of Turkey. By 2010, the number has increased to 3.7 million, while the migrant stock in Germany has decreased over the years. Inward migration The most recent reliable data on the foreign-born population in Turkey is taken from the 2000 Census; data was disseminated by the State Institute of Statistics in 2002. According to the Census, 1,278,671 foreign-born persons were in Turkey in 2000 which is less than 2% of the Turkish population. First five foreign-born groups were Bulgarian-, German-, Greek-, Macedonian- and Romanian-born. Until recently, immigration to Turkey was constituted exclusively by an ethnically Turkish population. In recent decades, however, Turkey has experienced the immigration of transit migrants, clandestine labourers, asylum-seekers and refugees. The influx of foreign nationals mostly from bordering and neighbouring countries has continued to increase. Added to this are the more recent legal migrations of professionals and skilled migrants and the ongoing immigration of foreign-national ethnic-Turks living in other countries. Total Number of Arrivals and Departures of Non-nationals by Year Arrival and departure statistics provide a basis for estimating people’s mobility in and out of Turkey. From 2006 to 2011, the number of non-nationals arriving in Turkey (one third from neighbouring regions, the Middle East, EU and CIS countries) increased to over 52%. Arrivals from CIS countries were markedly higher in 2010 and 2011. Main types of inflows are the migration of ethnic-Turks in the form of asylum, transit migration flows, illegal labour migration and registered migration of non-nationals (first three types often overlap). Turkey has become a major country of asylum since the 1980s. From late 1990s to the early 2000s, Turkey received approximately 5000-6000 asylum applications a year. The number reached 16,000 in 2011 leading UNHCR to announce Turkey as among the top five asylumreceiving countries in the world. Mass migration from Syria triggered by the uprisings and the civil war, started in spring 2011, has made of Turkey the third largest receiver of Syrian refugees after Lebanon and Jordan. The Socio-Political Framework of Migration Located at the junction of Europe, Asia and MENA (Middle East and North Africa), with Mediterranean and Black sea coasts, Turkey has always been one of the most important paths for large migration movements. Due to its geopolitical significance, Turkey became the nexus of emigration, immigration and transit migration. Closeness both to the EU Area and MENA made Turkey a crucial player in terms of migratory regimes. Turkey’s role became even more important in the aftermath of the Arab Spring which led to Syrian migration to Turkey. Turkey’s migration policy has changed considerably since the early 2000s in attempts to satisfy EU membership criteria. Among the reforms harmonizing Turkey’s legislation in the justice, freedom and security area with the EU acquis, the most important step was the Law on Foreigners and International Protection which has recently been approved by the Grand National Assembly. It will introduce a new legal and institutional framework for migration and asylum and was welcomed by the EU as a clear sign of Turkey’s efforts to establish an effective migration management system in line with EU standards. Despite the steps undertaken, there are three unresolved critical issues. First, Turkey applies a geographical limitation to refugees and does not recognize the status of refugees to persons from nonEuropean countries. To solve this dilemma, UNHCR intervenes to identify third country resettlement opportunities for non-European asylum seekers whose applications are approved. Without the guarantee of full-membership, Turkey is reluctant to lift the geographical limitation because of the fear of becoming a buffer zone. Second, due to her stable political atmosphere and Steady economic growth, Turkey became a magnet country pulling migrants from neighboring regions. The EU’s fear is not for Turkish nationals who may migrate to Europe following accession, but, instead, the irregular flow of third-country nationals who use Turkey as a transit country. Turkey’s visa-free policy with some of its neighbors (Syria, Lebanon, Iran, Egypt etc.) have caused serious concerns in the EU with respect to border management, especially since the crisis in Syria. According to the 2012 Progress Report39, the number of third-country nationals detected in 2011 by EU Member States when entering or attempting to enter the EU illegally and coming directly from or transiting through Turkish territory stood at 55,630. A readmission Agreement and a Visa Facilitation agreements scheme are under discussion. In June 2012, Turkey and the EU finalized the Readmission Agreement; however, it has yet to be signed due to Turkey’s understandable concerns at unfair burden sharing. The agreement’s ratification implies Turkey’s and the EU’s agreement to readmit illegal aliens within their borders. The EU, in turn, promises to lighten visa requirements for Turkish nationals. In addition to these constraints, Turkey faces a major challenge in the field of migration. Since the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, migration policy has been designed within the context of nation building with the intention of establishing a homogeneous identity. Hence, immigrants without Turkish descent and culture are seen as a threat to Turkish and Muslim identity. Turkey’s current ambition to become an EU member and the accompanying political liberalization is straining the state’s traditional concept of national identity.