Origins of ag - Nuffield College

advertisement

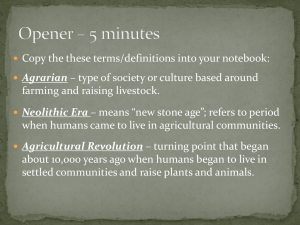

Origins of Agriculture and Private Property Bob Allen Nuffield College 2008 The emergence of agriculture is usually seen as progressive— a great step forward • • • • V Gordon Child called it the neolithic revolution Permitted permanent settlements Increased the food supply Ushered in civilisation – – – – – Writing and numbers Monumental architecture Private property The state A non-working elite With this view, it is obvious that agriculture was adopted as soon as it was thought of. The problem is explaining the great idea. But that’s not how it was: the standard of living fell when farming was adopted. • In many cultures, people became shorter. • Dental cavities and anaemia increased; other indicators deteriorated. • Farmers worked more hours per year than foragers. – Study of modern foragers. According to Larsen, “Biological Changes in Human Populations with Agriculture” (1995, p. 204), “The shift from foraging to farming led to a reduction in health status and well-being, an increase in physiological stress, a decline in nutrition, an increase in birthrate and population growth, and an alteration of activity types and [increased] work loads. Taken as a whole, then, the popular and scholarly perception that quality of life improved with the acquisition of agriculture is incorrect.” Steckel-Rose (2002) index of health declined from foraging at left thru agrarian civilizations. How can this paradox be explained? • Why did people take up farming if their standard of living declined? • Why didn’t agriculture improve human well being? • A test for any theory of the origins of agriculture is to reconcile farming with falling living standards. To answer these questions, we must develop a model • that distinguishes exogenous from endogenous variables • includes production and demography • incorporates feed back between the two • is based on the important ‘stylized facts’ of archaeology. Before developing this model, we will review the history of the ‘invention’ of agriculture. Agriculture appeared in seven regions between 4K and 10K years ago: I concentrate on the Near East where wheat, barley, lentils, flax, sheep, goats, pigs, cattle were domesticated. Habitats of wild progenitors of wheat & barley and area (in brown) where domestication occurred. Original habitat of wild sheep and area of domestication (% sheep bones in bone assemblages, 9000-8200 BP). The Natufians (14500-11500 BP) were the people who domesticated cereals. • They typically lived where hills met plains. • Gazelle lived on the plains and were hunted. • The hills contained oaks and pistachios which gave nuts as food. • Also on the hillsides were stands of wild wheat and barley, which they harvested. • They lived in semi-subterranean houses with stone foundations and probably wood superstructures. Natufian landscape Wild barley growing on a hillside Natufian tools included: • • • • Flat bladed sickles Mortars Grinding stones Storage pits • Abundance of tools for harvesting and preparing grain shows its importance in their diet. Sickle and grinding stones Modern foragers know a lot about the plants and animals they harvest. • How they reproduce. • How the environment affects their growth (they even garden them). • The realization that planting seeds yielded crops was not an intellectual breakthrough that precipitated farming since it was probably known for a long time. Domestication was inadvertent • Farmers began by planting wild seed and keeping wild animals. • Domestication implies biological changes that made wild varieties easier for human beings to manage. • Evidence of domesticated barley as early as 11000 BP. • Wheat domesticated by 9800 BP. • Sheep and goats about the same time. With animals, domestication meant that the animal got smaller. • Animals were tethered, and not fed very much. • They were smaller as a result. • Females, in particular, were smaller and had smaller birth canals. • They could no longer give birth to large offspring. • Inadvertent selection for genetically smaller animals. Wild sheep had bigger bones: Morphology of plants also changed • In the wild, seed cases were flimsy. • As a result, wild seed dispersed easily. • When humans harvested wild seed, it dispersed, and much of it was lost as it was harvested and taken to houses. • Domestication meant harder seed cases, which reduced losses. • Threshing was necessary to break seed cases. Brittle rachis and tough rachis How did this change happen? And without anybody knowing about it? • About one wild plant in 2 – 4 million had a tough racchis. • Humans could have inadvertently produced predominantly hard racchis seed (ie domesticate wheat) in 200 years, if they – Didn’t begin the harvest of wild seed until the grain was ripe and the soft racchis seed was falling to the ground. – Harvested wild wheat with a sickle and left grain that fell off on the ground. – Planted seed where it could not interbreed with wild seed. • Evidently, cultivation preceded domestication. • Domestication required a shift in the location of cultivation. Changes in temperature since end of ice age 15000 BP played a key role. (Younger Dryas) End of Ice Age The story goes like this: • Rise in temperature and rainfall 15K BP increased fertility of the environment and made it possible for the Natufians to harvest wild cereals. • The ‘younger dryas’ was colder and drier and made existing settlements unsustainable. • People moved and began cultivating wheat and barley near rivers. • This triggered domestication. • When climate improved, agriculture was more productive than foraging and displaced it. There may be some truth to this theory, but it is not the whole story. • The theory predicts a temporary fall in income as the climate deteriorated. • Then the standard of living is predicted to rebound. • That is not what happened. • To model this, we must include demographic model. We use a Malthusian positive check demographic model: Birth & Death rates BR=birth rate DR=death rate w = equilibrium income Income per person = food consumption/ head We need a production model with diminishing returns to labour: Food/ head w L labour The yellow productivity line could be either: • average product of labour – If the land is an open access common – If ‘residents’ have rights to use specific tracts of land so long as they live in the village and if those rights cannot be let or sold (like Russian mir). • marginal product of labour – If people have rights to specific tracts of land that they can use, sell, or lease as they like. For the moment, I assume that yellow line is the average product of labour. We can place the demographic and productivity graphs side by side and show the equilibrium: BR DR Food/ head w* L* 0 < = birth & death rates labour = > Any other wage and population levels generate population changes that move population towards w* and L* BR DR Food/ head w* w D>B (so L=>L*) 0 < = birth & death rates L* labour = > L We need to allocate labour between two activities, farming and foraging: food/ head food/ head w w 0 foraging labour = > < = farming labour 0 In this version of the diagram, there are only foragers, because foraging is always more productive: food/ head food/ head w w 0 foraging labour = > < = farming labour 0 Natufian foraging equilibrium Food/head BR DR foraging productivity on hill sides farming productivity by rivers foraging population Dry conditions led to farming and a fall in income Food/head BR DR lower foraging productivity on hill sides short run equilibrium with lower income & declining population farming productivity with wild seed by rivers foraging population farming population Note: The long run equilibrium is one in which there is no population! inadvertent seed selection makes farming competitive but income remains at foraging level Food/head BR DR foraging productivity forager = farming income farming productivity with domesticates foraging population productivity with wild seed farming population There are other themes that point to a more satisfactory theory: • Cohen (1977) advanced ‘population pressure’ as an explanation. – An objection is: why did the population grow without a food supply? • Hayden (1990)—competitive feasting • Weisdorf (2003)—manufactures – This may work in China where pottery was invented before grain was domesticated. Another important point of departure is that permanent settlements preceded farming • Inversion of the Child paradigm where agriculture leads to permanent settlements. • Established for the Natufians by Ofer bar Yosef who studied the noses of mice. • Explanation: rising temperature after last ice age increased fertility of the natural environment, reducing the distance people needed to wander to find food. Eventually, they could stay in one place and make day trips. Permanent settlement affected many aspects of human life: • Since people did not have to carry their babies, they could have more of them, and the fertility rate rose. – Ethnographic evidence – Expectation of life decreased • In some places, manufactures (eg pottery) were invented before farming • Communal activities like feasting The rise in fertility was probably the operative factor among the Natufians. • On its own, it was sufficient to lead to agriculture. • ‘Population pressure’ is involved, but why it occurred is clarified. • People avoided planting wild seed by rivers since that involved more work (removing other plants that were dominant). • They only planted seed by rivers when they became poor enough. • This analysis explains why the invention of agriculture was accompanied by a permanent fall in the standard of living. Natufian foraging equilibrium Food/head BR DR foraging productivity foraging income farming productivity foraging population sedentism leads to farming Food/head BR Higher Birth Rate DR foraging productivity forager income farming income farming productivity with wild seed foraging population Farming population inadvertent seed selection makes farming competitive Food/head BR Higher Birth Rate DR foraging productivity higher farming productivity with domesticates productivity with wild seed foraging population Farming population Notice that the sedentism theory: • Means that the adoption of agriculture is associated with population growth • The adoption of agriculture was accompanied by a permanent decline in the standard of living. • This theory can apply anywhere and may explain why agriculture was ‘discovered’ in so many places. The Younger Dryas theory can explain domestication, but it does not imply a permanent decline in the standard of living. • In the long run, income depends on birth and death rate functions. and they do not change under this scenario. • Dry conditions may have ‘nudged’ the Natufians towards planting seeds by rivers, but that would have happened anyway. The analysis assumes communal ownership of property with temporary individual use rights. • This was Marx’s primitive communism. • Are there any forces that would generate private property? • If there is enough heterogeneity in the land and people, then private property has efficiency advantages. Private property means that land can be leased or sold. • There can be non-working land lords (exploitation). • Labour is allocated across the land to equate the marginal product of labour rather than its average product. – With some simple functions, the allocation is the same. • If the allocation is different, then total output increases. • In that case, there are efficiency gains from private property, so winners can compensate losers. If land is homogeneous, so every plot has the same production function, then there is no advantage to private property. average products Marginal products OA OB Average product and marginal product curves intersect at the same labour value. If land is heterogeneous, then there is an advantage to private property. This triangle is the dead weight loss from communal property average products Marginal products OA A M OB If land is homogeneous, so every plot has the same production function, then there is no advantage to private property. • Q/LA = 1 – ¼ LA and Q/LB = 1 – ¼ LB and LA+LB=2 • Average product equalization => LA= LB=1 • Total product is Q = LA – ¼ LA2 • Marginal product is dQ/dLA = 1 – ½ LA • Equating marginal prod’s 1 – ½ LA = 1 – ½ LB • Implies that LA= LB=1 If land is heterogeneous, then there is an advantage to private property. • Q/LA = 1 – ¼ LA and Q/LB = 5/4 – ¼ LB and LA+LB=2 • Average product equalization LA= ½, LB=3/2 • Total product is Q = LA – ¼ LA2 • Q = 5/4 LB – ¼ LB2 • total product is 1.75. Marginal product equalization gives more output • • • • • • Marginal product is dQ/dLA = 1 – ½ LA Marginal product is dQ/dLB = 5/4 – ½ LB Equating marginal products: 1 – ½ LA = 5/4 – ½ LB Implies that LA= ¾ and LB= 5/4 Total product is 1.78125 With heterogeneous land, the invention of private property was socially progressive. Of course, the standard of living would not rise— only the population!