PowerPoint

advertisement

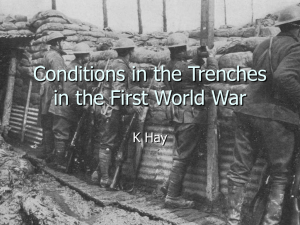

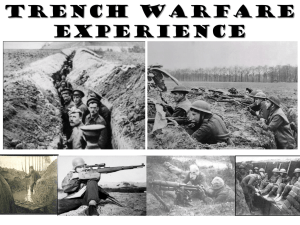

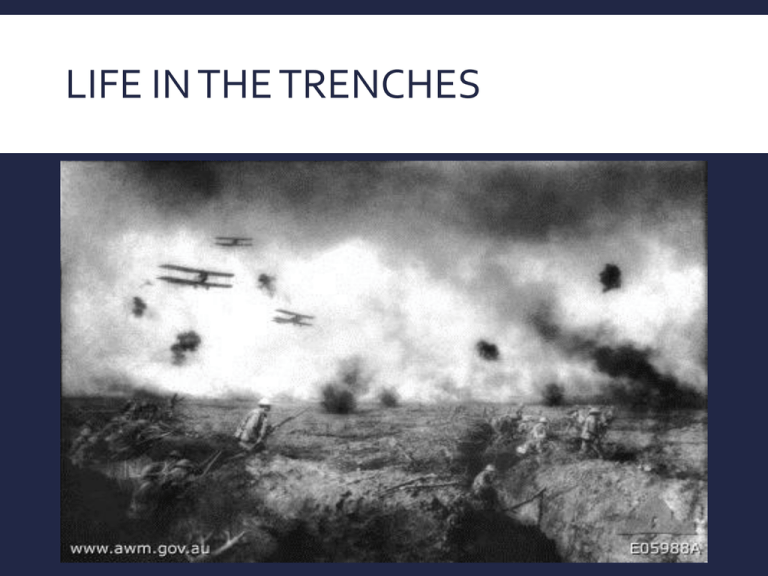

LIFE IN THE TRENCHES MUD Mud affected every aspect of a soldier’s life: what they ate, what they drank, how they breathed, what they wore, how they walked, their health. SOURCE 1 Mud... enveloped men of the front line. As a farm labourer at 'Akenfield', Davie was man used to hardship, but he was in no doubt about the importance of mud. 'Did you kill men, Davie?' 'I got several.' 'What was the worst, Davie?' 'Why, the wet, of course.' Where rain met bare earth or shelled earth, it spawned feet of mud. Boyd Orr reckoned that forty Englishmen a night were drowned in it. Nicholson on the Somme saw a man stuck fast for sixtyfive hours, with two men pulling on ropes finally freeing him though with his clothing sucked down by the mud. Winter, D, Oeath's Men, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1978, p. 96 SOURCE 2 Mud is the chief enemy and chief misery of the soldier. Mud soft and deep, that you sink into, vainly seeking a foothold on something solid: or stiff and clinging, gripping boots so firmly as sometimes to drag them off. Mud, that coats men, horses, guns, rifles, and all in a thick camouflage, so that they become almost indistinguishable from the ground. It clings to men's bodies and cracks their skins, and the slimy horror of it soaks their souls and sucks their courage. I have known those who can face an enemy barrage without flinching, who still shiver at the memory of their experiences in the mud of Flanders. Boyd, Sergeant P, Salvage, Australian War Memorial Facsimile Editions, Canberra [1918] 1983, in McAndrew, M, Thomas, D and Cummins, P, The Great War and Its Aftermath, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2001, p. 173 SICKNESS AND DISEASE It was not uncommon for the men in the trenches to have to stand for days at a stretch in knee-deep water. The lack of drainage and the constant rain meant that trenches were often full of water. This led to the condition called trench foot. This was a painful swelling of the feet caused by constant immersion in water. In some cases the toes could rot off and the condition advanced to gangrene which would frequently lead to amputation. SOURCE 3 Your feet swell to two or three times their normal size and go completely dead. You could stick a bayonet into them and not feel a thing. If you are fortunate enough not to lose your feet and the swelling begins to go down, it is then that the intolerable, indescribable agony begins. I have heard men cry with the pain and many had to have their feet and legs amputated. I was one of the lucky ones, but one more day in that trench and it may have been too late. Quoted in Brown, Tommy Goes to War SICKNESS AND DISEASE It was not only water that filled the trenches. The water at the bottom of a trench soon developed into a mixture of human and military waste. The stench of the trench, the smell of cordite (an explosive) and gas often caused vomiting. At the height of the battle men had no choice but to urinate and excrete where they stood. Diarrhoea, and, even worse, dysentery, were common illnesses. Decomposing bodies were allowed to float on the surface of the water until a safe time could be found to deal with them. SOURCE 4 On the next floor below are the abdominal and spine cases, head wounds and double amputations. On the right side of the wing are the jaw wounds, gas cases, nose, ear, and neck wounds. On the left the blind and the lung wounds, pelvis wounds, wounds in the joints, wounds in the testicles, wounds in the intestines. Here a man realizes for the first time in how many places a man can get hit. Two fellows die of tetanus. Their skin turns pale, their limbs stiffen, at last only their eyes live stubbornly. Many of the wounded have their shattered limbs hanging free in the air from a gallows; underneath the wound a basin is placed into which the pus drips. Every two or three hours the vessel is emptied. Other men lie in stretching bandages with heavy weights hanging from the end of the bed. I see intestine wounds that are constantly full of excreta. The surgeon's clerk shows me X-ray photographs of completely smashed hip-bones, knees, and shoulders. A man cannot realize that above such shattered bodies there are still human faces in which life goes its daily round. And this is only one hospital, one single station; there are hundreds of thousands in Germany, hundreds of thousands in France, hundreds of thousands in Russia. Remarque, EM, All Quiet on the Western Front, Little Brown, Boston, 1929, pp. 265-6 LICE – SOURCE 5 Jack, like most of the men, scratched almost all the time, unconsciously, and gradually, less aware that he did so. Not all of them were resigned. Tyson had once been driven so frantic that the medical officer ordered him to have fifteen days' rest. The constant irritation had proved more wearing to him even than the sound of heavy guns or the fear of dying ... By the time they had reached their billets Jack felt the first irritation on his skin. Within three hours the heat on his body as he marched had hatched the eggs of hundreds of lice that had lain dormant in the seams of the shirt. By the time h reached the front his skin was alive with them. Faulks, S, Birdsong, Vintage, London, 1994, pp. 346, 347. RATS The rats that infected the Western Front were unlike anything the men had seen before. Known as ‘trench rats’ they were sometimes the size of small dogs. Rats did not limit their interests to the dead. A sleeping soldier was an equally good target. However, the horror of the rats often brought out the humour of the men in the trenches. There are many accounts of soldiers describing their competitions to kill rats. Some soldiers even developed some affection for ‘their rats’ and gave them names. SOURCE 6 The outstanding feature of the Armentieres sector was the extraordinary number of rats. The area was infested with them ... It was impossible to keep them out of the dugouts even. They grew fat on the food that they pilfered from us, and anything they could pick up in or around the trenches; they were bloated and loathsome to look at ... One night a rat ran across my face. Unfortunately my mouth happened to be open and the hind legs of the filthy little beast went right in. Dolden, AS, Cannon Fodder, Blandford Press, 1980, in Fewster, S, The First World War, Longman, Harlow, 1990, p. 25 GAS GANGRENE The soil in northern France contains manure that had a bacterium in it that produces germ cells when exposed to oxygen. If this came into contact with a wound, which was quite easy given the constant mud, it caused a condition called gas gangrene. This condition has nothing to do with gas. SOURCE 7 After forty-eight hours the edges of the wound begin to swell up ... The cut surface takes on a curious half-jellied, half-mummifed look; then the whole wounded limb begins to swell up and distend in the most extraordinary fashion, turning, as it does, first an ashy white and then a greenish colour. This is because the tissues are being literally blown out with gas. Ringer, RE, 2 Unit Modern History Outlines, Core Study, Pergamon, Sydney, 1989, p. 73 THE COLD In the trenches winter temperatures were known to fall to -15oC. For the soldier forced to spend weeks on end in a trench, the cold caused unbelievable hardship. It was impossible to escape the cold and no amount of extra clothing was able to keep it out. The combination of cold and wet made life unbearable. The cold also brought frostbite which often led to infection, gangrene and later amputation. The cold made sleep almost impossible. THE PSYCHOLOGICAL ANGLE The suffering of the men in the trenches was not only physical. It also had psychological effects which is hardly surprising. Most of the men who fought in the war were not used to the violence of battle and they suddenly found themselves having to cope with the constant artillery barrage, the sight of human flesh torn apart and the stench of the trenches. Many were unable to cope and cracked under the strain. SOURCE 8 Although this source is taken from a fictional book the author researched extensively. The wall of the trench had caved in and barbed wire had been blown back and was hanging over the churned earth. There was a sound of groaning. Stretcher-bearers were trying to clear the debris to get to the wounded men. Stephen took a trenching tool and began to dig. They pulled out a man by his shoulders. It was Reeves. His expression was more vacant than usual. His rib cage was missing on one side where a large piece of shell casing stuck out from under his breastbone ... A few yards further on they disinterred Wilkinson ... He prepared words of encouragement as he came alongside. But as the stretcher-bearers lifted him, they turned his body and Stephen saw that his head was cut away in section, so that the smooth skin and the handsome face remained on one side, but on the other were the ragged edges of skull from which the remains of his brain were dropping on to his scorched uniform. Faulks, S, Birdsong, Vintage, London, 1994, pp. 154-5 SOURCE 9 Companies of Royal Engineers, composed of specially selected British coal miners, worked in shifts around the clock digging tunnels towards the German line. When a tunnel was completed after several days of sweating labour, tons of explosive charges were stacked at the end and primed ready for firing ... At the moment of the explosion the ground trembled violently in a miniature earthquake. Then like an enormous pie crust rising up, slowly at first, the bulging mass of earth crackled in thousands of fissures as it erupted ... Hundreds of tons of earth hurled skywards to a height of three hundred feet or more, many of the lumps of great size. A state of acute alarm prevailed as the deadly weight commenced to drop ... Coppard, G, With a Machine Gun to Cambrai, HMSO, London, 1969, in Fewster, S, The First World War, Longman, Harlow, 1990, p. 55 SHELL SHOCK Shell shock was caused by the stresses of war at the front. Different people displayed this in varying ways: - some men became violent and angry and had to be physically held back - some men turned inwards and totally refused to communicate - some would look as if they were in another world - others might shake and mumble SOURCE 10 ... the 'shell-shocks' sat about, dumb, or making queer, foolish noises, or staring with look of animal fear in their eyes. From a padded room came a sound of singing. idiot of war was singing between bursts of laughter. It all seemed so funny to that war, so mad! ... The nervous cases were the worst and in greatest number. Many went raving mad. The shell-shock victims clawed at their mouths unceasingly, or lay motionless like corpses with staring eyes, or trembled in every limb, moaning miserably and afflicted with great terror. Gibbs, P, Now It Can Be Told, Harper & Brothers, London, 1920, pp. 350, 438 SOURCE 11 When men did crack, they often showed the most diverse responses to identical pressures. Myers noted one incident in which a shell had hit a dugout. Only two men survived. One wandered in the open with his clothes off, believing that he was going to bed. After just four days at a field ambulance station he was back in service. The other man was in a coma for a fortnight with rigid limbs. On the seventeenth day he sat up and said, 'Did you see that one, Jim?' then relapsed, remaining deaf and mute. In a final hysterical seizure he shouted battlefield orders, then came round to his normal condition. Another man who came under Myers was a soldier who had seen his closest friend killed at his side. He went into a tearful semi-stupor, showed no reflexes and took no notice of pinpricks. After two days, however, he got out of ed and talked to his orderly quietly about his old civilian life but retained no memory whatsoever of anything in his war hitherto. Winter, D. Death’s Men, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1978, p. 136 AFTER EFFECTS For some men the trauma of the war left them once they returned home but it stayed with others forever. The rat-a-tat-tat sound of a 1920s motorcycle was often enough to lead an ex-soldier to throw himself onto the ground in order to seek cover from what he thought was enemy fire. As late as 1938, there were 32, 000 World War I veterans being treated in psychiatric hospitals. BIBLIOGRAPHY World War I: From Sarajevo to Versailles 2nd edition, Ken Webb. 2006 Evidence of War 2nd edition, Anne McCallum. 2000