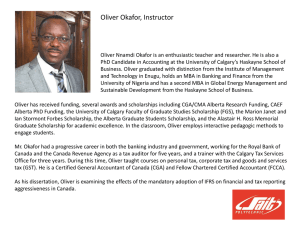

Oliver Twist Power Point

advertisement