Honors Project - How Long Does A Sterile Field

advertisement

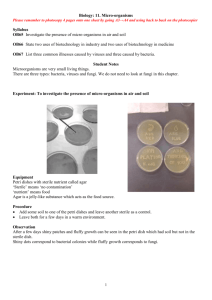

How Long Does A Sterile Field Remain Sterile? by Rebecca A. Burns, SUNY Canton, Canton New York ABSTRACT This experiment was conducted to show the likelihood of contamination of a petri dish by bacteria when left exposed. The number of bacterial colonies that grew on exposed petri dishes were counted to determine the amount of contamination over a period of 1, 15, and 30 minutes. The number of bacterial colonies and molds that grew on each dish increased generally with the amount of time exposed. Therefore, it was clear that microbes are present in the air and can contaminate materials in as little as one minute. DISCUSSION Figure 2: Solidified agar exposed to the environment Figure 1: Pouring melted nutrient agar into a petri dish PROCEDURE The following procedure was carried out by students in Biology 209: Introduction to Microbiology this spring 2014 semester. Each student in five laboratory sections was randomly assigned to a different time treatment. INTRODUCTION 1. Melt and temper enough nutrient agar to pour all plates from the same sample of agar. 2. Pour agar into petri dishes and allow dishes to solidify. (See figure 1). Keep lids on to prevent contamination, but leave space for excess moisture to escape. 3. Remove the lids from the first set of petri dishes, and leave exposed to the air for one minute. (See figure 2). 4. Expose the second set of plates for 15 minutes. 5. Expose the third set of plates for 30 minutes. 6. Replace all petri dish lids after appropriate amount of time. 7. Label petri dishes and incubate inverted at room temperature (22°C) for 7 days. 8. Count the number of colonies grown on each plate. When conducting experiments, it is important to maintain a sterile field to prevent undesirable contamination. “Sterile field” has different meanings in different situations, however. In medical situations, a sterile field is established and strictly maintained for operations and procedures. Individuals must face the operating table at all times, as their back is not sterile, and only certain areas, such as disinfected, gloved hands, on that person are considered sterile. In the experimental lab, the “sterile field” is maintained by disinfecting the countertop, working with clean instruments and materials, and always having unsoiled hands. To reduce contamination when using petri dishes, the lid is left on unless material is being placed in the dish. When agar is poured or a lawn culture of microorganisms prepared, the lid is only lifted slightly to prevent contaminants from entering the culture. Are these precautions necessary? Would material really be contaminated in a short space of time? Where would the microorganisms come from? Figure 5: 30 minutes of exposure to the environment and 7 days of incubation Number of Colonies of Bacteria Average Number of Microbial Colonies Per Plate for Trials 1 & 2 Figure 4:15 minutes of exposure to the environment and 7 days of incubation Where did the contaminants come from, though? There are microbes, including bacteria, viruses, molds, and other microorganisms in the outdoor air all the time. Out-of-doors, microbes are blown around by the wind, carried by dust particles, and are present on every organism and on nonliving material. There are more than 1,800 different kinds of bacteria present in the air at any one time (Krotz) and over a 1,000 species of bacteria living on our skin alone (Grice et al.). The majority of these are harmless or beneficial, but many bacteria and other microbes are pathogenic. Airborne microbes enter indoor environments by blowing in through a window, carried by human clothing and skin, and even by breathing. The dust in a room has been found to contain the greatest amount of bacteria, in comparison with indoor air, outdoor air, and dust from ventilation ducts (Gould). Humans are the greatest culprits for microbial contamination. We bring microbes into a room by entering, and in moving around, we stir up the dust and cause more microbes to fly through the air. Crowded conditions increase the spread of bacteria and viruses and the chance of contamination (Bact.). A full lab could potentially increase the risk of contamination because there are more people moving dust and air around and contributing to the amount of microbes in the air. RESULTS The petri dishes exposed for 1 minute grew an average of two colonies (see figure 3). The samples exposed for 15 minutes grew an average of 10 colonies on each plate (see figure 4). The plates exposed for 30 minutes grew an average of 21 colonies of assorted bacteria and molds (see figure 5). Figure 3: After 1 minute of exposure to the environment and 7 days of incubation The results strongly suggest that the longer petri dishes are exposed to the air, the more bacteria and mold spores fall on the dishes and grow colonies. Clearly, more time exposed results in more contamination, although it was noted that the amount of variation within each treatment is large. 25 20 21 15 10 10 5 0 It is necessary, therefore, when conducting experiments, to follow proper procedures for reducing contamination. The microbes flying throughout the air must be kept out of mediums for accurate results of many experiments and tests. W\hen working in the lab, avoid moving quickly and turning your back to the lab bench. This could help reduce the amount of air flow in the room and, consequently, decrease the chances of contamination. In addition, it would be best to decrease the number of people in a lab at one time. In any situation that requires the absolute maintenance of a sterile field (e.g. a surgical room) it is necessary to wear sterile gloves, gowns, face masks, head coverings, and shoes coverings in order to minimize the likelihood of microbes from our hair, skin, or clothing from entering the air and the sterile field. Works Cited: “Bacteria and Viruses.” American Lung Association. http://www.lung.org/healthy-air/home/resources/bacteria-and-viruses.html. 2013. Web. 12 Apr. 2014. 2 Time of exposure to air (minutes) 1 minute 15 minutes 30 minutes Gould, S.E. “How Bacteria Get into Your Home.” Scientific American. July 15, 2013. Web. 12 Apr. 2014. Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S. (2009). Topographical and Temporal Diversity of the Human Skin Microbiome, Science, 324: 1190 - 1192. Krotz, Dan. “Study Finds the Air Rich with Bacteria.” Berkeley Lab. 2006. Web. 12 Apr. 2014. April 14, 2014