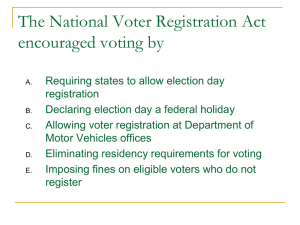

Regulation of employee political activity

advertisement

Regulation of employee political activity Leon J. Page Deputy County Counsel (714) 834-6238 Overview -- Four lines of cases TYPE ONE: Public employer enacts a policy regulating employee political activity that is then challenged by employees or labor organization on First Amendment grounds. Overview -- Four lines of cases TYPE TWO: Public employer takes an adverse employment action against employee and the employee sues, alleging unlawful retaliation in violation of employee’s First Amendment speech rights. Overview -- Four lines of cases TYPE THREE: Public employee uses County or public resources to expressly advocate for the election or defeat of a candidate or ballot measure. Overview -- Four lines of cases TYPE FOUR: Local government employee holding a position funded by federal loans or grants becomes a candidate in a partisan election. Employer policy regulating political activity – Type One Example: Local city council adopts a policy prohibiting city employees from making political contributions, circulating a signature petition, wearing campaign buttons, serving as a delegate, and actively participating in fundraising for a partisan candidate. Employee or union sues and challenges policy on First Amendment grounds. Employer policy regulating political activity – Type One The Courts will balance the employee’s interest in commenting upon matters of public concern against (1) the need to have fair and effective government, and (2) the need to ensure that employees are free from pressure to perform “political chores.” Employer policy regulating political activity – Type One Generally, the Courts have been fairly deferential to public employer efforts to adopt policies regulating or limiting public employee political activity, even political activity outside of work and away from the workplace. Employer policy regulating political activity – Type One See also recent California Supreme Court decision, San Leandro Teachers Association v. Governing Bd. Of San Leandro Unified School District, 46 Cal.4th 822 (2009) (School district could lawfully prohibit teachers’ union from distributing campaign literature regarding school board candidates in school mailboxes.) Employee speech retaliation cases – Type Two Example: Employee of a local city government openly opposes the election of a city mayoral candidate by writing a letter to the editor of a local newspaper. Mayoral candidate wins. Employee is discharged and then sues, claiming retaliation. Employee speech retaliation cases – Type Two The government may not force its employees to relinquish their First Amendment rights to free speech and free association. However, in the interest of an efficient workplace, the government may regulate free speech within certain guidelines. “Four plus one” analysis is required. Employee speech retaliation cases – Type Two Four elements to prove a First Amendment retaliation claim: 1) Employee suffered an adverse employment action; 2) Employee’s speech was about a matter of public concern; 3) The interest of the employee in speaking must outweigh the employer’s interest in an efficient workplace (see below.) 4) The speech must have motivated the adverse employment decision. Employee speech retaliation cases – Type Two However, even if the plaintiff can demonstrate all four elements, a public employer may still escape liability if it can show “that it would have taken the same action even in the absence of the protected conduct.” Mt. Healthy City Sch. Dist. Bd. of Educ. V. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274, 287 (1977). Factor No. 3: When does the employee’s interest in speaking ever outweigh the employer’s interest in an efficient workplace? 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Whether the employee’s actions involve public concerns; Whether close working relationship are essential to fulfilling the employee’s public responsibilities (i.e. did the speech affect working relationships necessary to the Dept.’s proper functioning?”); The time, place, and manner of the employee’s activity; Whether the activity can be considered hostile, abusive, or insubordinate; and Whether the activity impairs discipline by superiors or harmony among co-workers. Employee speech retaliation cases – Type Two Example: Police officer discharged for having campaign sign (supporting another candidate) in the trunk of the officer’s patrol vehicle. No real impact on efficiency of the police department. Case ordered to trial. Employee speech retaliation cases – Type Two Employees who had participated in fund raisers, worn their candidates paraphernalia, gone door to door canvassing, put yard signs in their yards and bumper stickers on their personal vehicles had minimal impact on the efficiency of police department. Brady v. Fort Bend County, 145 F.3d 69 (5th Cir. 1998). Employee speech retaliation cases – Type Two But compare Connealy v. Walsh, 412 F. Supp. 146 (1976). Plaintiff social worker displayed “McGovern” political bumper sticker on car parked in employer’s parking lot, in violation of employer’s policy. Court held that employer’s interests outweighed employee’s First Amendment rights. Employee speech retaliation cases – Type Two And compare Smith v. United States, 502 F.2d 512 (5th Cir. 1974). Clinical psychologist employed by Veteran’s Administration wore a “peace pin” on his lapel, in violation of policy. Discharge upheld; wearing of pin not protected by First Amendment. Employee speech retaliation cases – Type Two • • • So what about the city employee who writes the letter opposing the ultimately successfully mayoral candidate and is then discharged? It depends. Let’s review the factors – slides 11-13. What position does the employee hold? Employee speech retaliation cases – Type Two “Policymaker” exception: High level officials can fire certain types of governmental employees for purely political reasons without offending the Constitution. “The ultimate inquiry is not whether the label policymaker' or 'confidential' fits a particular position; rather, the question is whether the hiring authority can demonstrate that party affiliation is an appropriate requirement for the effective performance of the public office involved.” Branti v. Finkel 445 U.S. 507 (1980). Misuse of Public Funds – Type Three The starting point for any analysis concerning the misuse of public funds begins with the principle that public funds must be expended for an authorized public purpose. An expenditure is made for a public purpose when its purpose is to benefit the public interest rather than private individuals or private purposes. Misuse of Public Funds – Type Three In People v. Battin, a county supervisor used his county compensated staff to work on his political campaign for Lieutenant Governor. In Stanson v. Mott, a private citizen sued the Director of the California Department of Parks and Recreation, challenging the director’s expenditure of Department funds to support passage of a bond act appearing on a statewide ballot. The Supreme Court unanimously found that the director had acted unlawfully, concluding that “in the absence of clear and explicit legislative authorization, a public agency may not expend public funds to promote a partisan position in an election campaign.” Misuse of Public Funds – Type Three The Supreme Court wrote in Stanson: “A fundamental precept of this nation’s democratic electoral process is that the government may not ‘take sides’ in election contests or bestow an unfair advantage on one of several competing factions. A principal danger feared by our country’s founders lay in the possibility that the holders of governmental authority would use official power improperly to perpetuate themselves, or their allies, in office....” Hatch Act – Type Four Generally, the Hatch Act regulates individual employees, not federal, state or local agencies. Under the federal Hatch Act, 5. U.S.C. §§ 1501 – 1508, certain state and local employees are prohibited from being candidates in a partisan election, i.e., an election in which any candidate represents, for example, the Republican or Democrat Party. Hatch Act – Type Four Notably, the Hatch Act’s prohibition against candidacy “extends not merely to the formal announcement of candidacy but also to the preliminaries leading to such announcement and to canvassing or soliciting support or doing or permitting to be done any act in furtherance of candidacy.” See June 17, 2009, U.S. Office of Special Counsel advice letter, available at http://www.osc.gov/documents/hatchact/fe deral/Adams%20AO%20redacted.pdf.) Hatch Act – Type Four Under 5 U.S.C. § 1504, when a federal agency that awards federal funds has reason to believe that a state or local officer or employee holding a position financed by federal funding has violated a provision of the Hatch Act (by, for example, becoming a candidate in a partisan election), that federal agency is required to report the matter to the U.S. Office of the Special Counsel, the agency that is responsible for Hatch Act enforcement. Hatch Act – Type Four • • If the Special Counsel determines that the federal agency’s report warrants an investigation, the Special Counsel is required to investigate the matter and present its findings and charges to the Merit Systems Protection Board (“MPSB”). The MSPB is required to conduct an evidentiary hearing on the alleged violation. Hatch Act – Type Four After hearing the evidence, the MSPB is required to (1) determine whether the employee violated the Hatch Act; (2) determine whether the violation warrants the removal of the officer or employee from his or her state or local office or employment; and (3) notify the employee and the employing state or local agency of its decision. Hatch Act – Type Four Under 5 U.S.C. § 1506, if the state or local employee has not been removed from his or her office or employment within 30 days of the MSPB’s directive, or if the employee has been removed, but is then reappointed to another position at the state or local agency within 18 months after his removal, the MSPB shall certify an order requiring that the appropriate federal agency withhold from its loans or grants to the state or local agency an amount equal to 2 years’ pay at the rate the officer or employee was receiving at the time of the violation. Conclusions… • • • • Courts are generally deferential to public employer regulations of employee political activity, even away from the workplace. First Amendment retaliation claims extremely fact-intensive; Public resources may not be used to promote candidates or ballot measures; Federal Hatch Act regulates certain local employees holding positions funded by federal loans or grants. Conclusions… • • • The balancing of the public employer’s interest in efficiency against the employee’s First Amendment speech right is extremely difficult. In First Amendment retaliation cases, courts have reached seemingly contradictory results. Please consult with County Counsel before taking adverse action against employee because of his or her political activity.