From Prehistory to the First River

advertisement

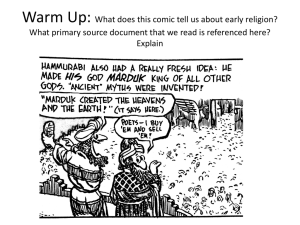

First River Valley Civilizations Tracy Rosselle, M.A.T. Newsome High School, Lithia, FL Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Indus River Valley Four to five thousand years after the Neolithic Revolution, the first full-blown civilizations arose in the Middle East and on the subcontinent of India. Mesopotamia (“land between the [Tigris & Euphrates] rivers”) Egypt Indus Fertile Crescent Mesopotamia Part of larger area known as Fertile Crescent A series of ancient civilizations – Sumer, Babylon, Persia – thrived here. Written record begins with Sumer, in southern part of Mesopotamia, where by 3000 BCE perhaps 100,000 people lived. Sumerian civilization Sumer developed as a collection of city-states, surrounded by fields of barley and wheat. Water from the rivers – which flooded often and unpredictably – was central to the civilization. Shared culture but separate governments: each citystate (Ur, Uruk, Kish, etc.) had own ruler, own god. Sumerians were polytheistic (worshipped more than one god), believing natural events were caused by the gods harsh life, frequent flooding and invasions transmitted to a religion of “rough” gods. To the temple Scholars still debate the function and symbolic meaning of ziggurats, which were made of mud-brick and approached by ramps and stairs. Sumerians built centrally located, pyramid-like temples called ziggurats to appease their angry gods. Earliest governments controlled by temple priests … but by third millennium BCE there emerged a lugal, or “big man.” From the top down The “big man” was what we would call a king. The idea of royalty emerged, and kings soon assumed many responsibilities: upkeep and building of temples and proper performance of religious ritual (Sumerians believed in magic); maintaining city walls and defenses, and warding off foreign attacks; extending and repairing irrigation channels; guarding property rights; and establishing justice. The Sumerian social order Some kings claimed divinity but they usually portrayed themselves as the deity’s earthly representative. Practice of hereditary succession emerged. Below the kings were priests and priestesses (often related to the king). Lower down the social order were free commoners (peasants, builders, craftsmen) and then dependent clients (owned no property), both of whom paid taxes with surplus or labor. Slavery from the very beginning At the very bottom of the Sumerian social pyramid were the slaves, who worked as agricultural laborers or domestic servants. Note that from the earliest civilization on record, slavery has existed in one form or another. It is a significant social and economic continuity throughout most of human history. Slaves were often made of conquered enemies, and some people even sold themselves into slavery. Later on, we’ll see how the Atlantic slave trade was especially pernicious and unique. The role of women Males dominated the position of scribe, and what they wrote mostly reflects elite male activity. Scholars theorize that women lost social standing and freedom with the spread of agriculture. Bearing and raising children and maintaining the home became primary occupation of many women … but some worked in primitive textile factories and breweries, or as prostitutes, tavern keepers, bakers or fortune-tellers. Women had some rights: they could own property, maintain control of their dowry (property a woman brings to her husband at marriage) and engage in trade. Mesopotamian science and technology Historians believe Sumerians invented the wheel, the sail and the plow. Other Mesopotamian advancements: Cuneiform – a system of writing on clay tablets, using graphic symbols to represent sounds, syllables, ideas, physical objects. Math & geometry – developed a number system in base 60, from which we get modern units for measuring time and the degrees of a circle (60 seconds, 360 degrees). Metallurgy – bronze and then iron by 1000 BCE. Mesopotamian myth The Epic of Gilgamesh – (c. 2000 BCE) Mesopotamia’s greatest work of literature, it was an epic poem of about 3,000 lines that addressed Mesopotamia’s mythic answer to the most profound question of all: What is the meaning of life and death? Myth – a vehicle through which prescientific societies explain the workings of the universe and humanity’s place within it. Terrifying conditions & visions Gilgamesh, the Mesopotamian hero, is confronted with “terrifying visions of the afterlife: disembodied spirits of the dead stumbling around in the darkness of the Underworld for all eternity, eating dust and clay, and slaving for the heartless gods of that realm.” – The Earth and Its Peoples, p. 33 As you reflect on Mesopotamia and Egypt, consider how their respective environments shaped their worldviews and religious practices. How was the Mesopotamian view of the afterlife different from the Egyptian? War and trade Mesopotamian peoples quarreled often but also traded with one another – as well as other civilizations – extensively. Trade networks, in fact, extended far and wide: Donkey caravans to Anatolia (tin and textiles for silver), Lebanon (for cedar wood), Egypt (for gold) and northern India (for semiprecious stones). Watercraft sailed through the Persian Gulf and Arabian Sea: Sumerian merchants shipped woolen textiles, leather goods, sesame oil and jewelry to India in exchange for copper, ivory, pearls and semiprecious stones. After Sumer By 1700 BCE Sumerian civilization had been completely overthrown, but subsequent conquerors adopted many Sumerian traditions and technologies. Supplanting the Sumerians, in succession: Akkadians – speakers of a Semitic language (Semitic refers to a family of languages spoken in western Asia and northern Africa, including Hebrew, Aramaic, Phoenician and modern-day Arabic), who developed first known code of laws. Babylonians – Code of Hammurabi (King of Babylon) was first major step toward the idea of the “rule of law,” distinguishing between major and minor offenses and applying it to nearly everyone. After Sumer (cont.) Hittites – dominated region* by 1500 BCE, becoming a military superpower because of their use of iron in weapons. Assyrians – learned to use iron technology from the Hittites and established an empire across the Fertile Crescent; ruthlessly sent large groups into exile after uprisings (which further enhanced cultural diffusion – the process by which a product or idea spreads from one culture to another). * Remember, with the succession of Summer, Akkad, Babylon, etc., we’re still talking about Mesopotamia. After Sumer (cont.) Chaldeans – King Nebuchadnezzar rebuilt Babylon as a showplace of architecture and culture, only to see his empire fall to a new civilization called the Persian Empire – a major world force we’ll discuss later on. Egypt At roughly the same time as Mesopotamia, Egyptian civilization emerged along the Nile River, the world’s longest. Narrow region along the banks supports lush vegetation amid surrounding deserts. Upper Egypt to the south, Lower Egypt to the north. Predictable flooding = stable agriculture, surplus. The impact of natural environment The Nile River Unlike Mesopotamia, Egypt’s natural isolation fostered a unique culture with long periods of relative stability. Basic features of society and politics took shape during Early Dynastic (3100-2575 BCE) and Old Kingdom (25752134) periods. From old to new Civil war brought about First Intermediate Period (2134-2040) Middle Kingdom lasted from 2040-1640 BCE, after which the Hyksos conquered it. A century later, the New Kingdom (1532-1070 BCE) was established, during which the ancient Egyptians reached their peak, militarily conquering – especially under Ramses II (1304-1237 BCE) – vast territories in northern Africa and the Middle East, including Palestine, Syria and parts of Asia Minor. Centralized rule Even more so than the Mesopotamians, the ancient Egyptians developed centralized society, presided over by a monarch called a pharaoh and a small caste of priests. The pharaoh was considered the living incarnation of the chief deity, the sun god Re (“ray”). The benevolent rule of the pharaoh and the Egyptians’ conception of a divine king as the source of law and order may explain the absence of an impersonal law equivalent to Hammurabi’s Code. From the top down Egyptian social structure Pharaoh – owned all the land and goods produced on it. Priests Nobles Merchants and skilled artisans Peasants – expected to give over half of what they produced to the kingdom. Slaves – limited and of little economic significance; usually prisoners of war or their descendents. You can take it with you Egyptians were polytheistic, having an elaborate religion that included the idea of life after death. Egyptian Book of the Dead – the most important religious text, detailing what happens to the soul and how to reach a happy afterlife. The afterlife was central to the most famous aspects of Egyptian civilization: mummification (the art of preserving bodies after death) and the building of gigantic tombs (including the pyramids, which were meant to provide resting places for pharaohs after they died). The Pyramids of Giza These pyramids – the largest of which, the Great Pyramid, is nearly 500 feet tall – are thought to have taken more than 80,000 laborers 20 years to build. Technological progress In addition to building great pyramids, Egyptians were talented makers of bronze tools and weapons. They developed great knowledge of medicine, mathematics and astronomy … and devised the 365-day calendar that, with minor modifications, is still used today. Hieroglyphics The Egyptian writing system consisted of a series of pictures (hieroglyphs) that represented letters and words. We can read ancient Egyptian writing only because of the 19th-century CE discovery of the Rosetta Stone, a 2ndcentury BCE inscription that gave hieroglyphic and Greek versions of the same text. Paper’s precursor Papyrus, a paper-like product that could be written on with ink, was invented in Egypt and exported in large quantities for scribes throughout the ancient world. Made with the stems of papyrus reeds, which grew abundantly in the Nile marshes: laid in a grid pattern, moistened, then pounded with a soft mallet until they adhered into a sheet. Egyptian women History’s first known female ruler was Queen Hatshepsut (22-year reign during New Kingdom), who is credited with greatly expanding Egyptian trade expeditions. Women had relatively high status in ancient Egypt – they could express themselves more freely than Mesopotamian women; could buy, sell, inherit and will property as they chose; could dissolve their marriages – but were still expected to be subservient to men. Trade networks Ancient Egypt was less urban than Mesopotamia, and – because of its relatively isolated location – was at less of a trading crossroads. Nevertheless, over time they did build up cities and a sizable economic network. They needed a constant supply of timber and stone for building projects, and their culture prized luxuries such as gold and spices. Egyptian art reflects societal values “Because the Egyptians had no feeling that events of the moment were transitory, they viewed the present as eternal. The world was static; what seemed like change was only recurrence of the eternal order. Thus, Egyptian literature does not contain careful records of the deeds, or distinctive characteristics of the pharaohs. Rather they are portrayed as the divine ideal, always just, wise, bold, strong, and victorious. (continued) Egyptian art “Neither did artists depict events to be remembered for their uniqueness; instead they tried to show the typical and ideal. The aim of the artist was to portray the eternal nature of his subject, independent of time and space, and this aim eventually crystallized into a set of stylistic formulas. Each figure was painted partly in profile, partly in frontal view … not pictorially but symbolically … The static quality of Egyptian art was heightened by the absence of perspective.” From Antiquity, by Norman Cantor, p. 62. Wall painting of an Egyptian queen The Indus Valley Civilization Discovered in the early 20th century, this mysterious ancient civilization (c. 25001500 BCE) stretched for more than 900 miles along the Indus River in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, which is present-day Pakistan. Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro Archaeologists have found as many as 1,500 communities that thrived along the Indus River, which was an excellent transportation system that provided access to the Arabian Sea. Two biggest urban sites, supporting 30-40,000 inhabitants: Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, from which we get the term Harappan civilization (or society). All of what we know of this civilization comes from the archaeological record because its writing system of more than 400 signs has not been deciphered. Cities on a grid In contrast to early Mesopotamian cities, which were jumbled mazes of irregular buildings made of sundried mud bricks, Harappan cities were more sophisticated: buildings and streets laid out in precise grids. buildings constructed with oven-baked bricks cut in standard sizes. extensive and modern-looking indoor plumbing, with showers and toilets with wooden seats, and pipes connecting each house to an underground sewer system. A look at the modernday excavation of Mohenjo-Daro: a street, above, and an alley, right. Industrious people on the Indus Cities were built on mud-brick island platforms and surrounded by levees, or earthen walls, to keep floodwaters out. Consistent width of streets and length of city blocks, and uniformity of construction techniques suggest strong central authority – perhaps a theocracy housed in the citadel, an elevated, enclosed compound with large buildings. Well-ventilated structures near citadel may have stored grain for local use and export (grain also collected as taxes). Presence of barracks may point to some regimentation of skilled artisans. Metal for everyone! Unlike in other regions, tools and other useful objects were valued more so than decorative pieces like jewelry, and metal itself was more democratized in the Indus Valley – it wasn’t just an elite possession. Harappan culture Housing – with functional rather than creative architecture – suggests social divisions were not great, but there was a clear difference between rich and poor. Scarcity of weapons suggests limited conflict or threat of invasion (recall the geography of the Indian subcontinent, capped by the world’s largest mountains). Harappan artifacts such as clay and wooden children’s toys, and games, such as the chessboard above, suggest prosperity and time for leisure activities. Harappan culture (cont.) A 5-inch bronze figure of a young dancer. Relatively little has survived that reflects creativity of Harappan peoples, but their painted pottery rivals contemporary work elsewhere. Sculpture was clearly their highest artistic achievement, showing vitality of expression. Harappan religion Scholars believe the society was a theocracy (government headed by divine authority), but no temples have been found. Although it’s still speculative, some scholars see links between Harappan religious artifacts and Hinduism, which later emerged in India: Figures show what may be early representations of Shiva, a major Hindu god (“destroyer of the world”). Other figures may relate to a mother goddess, fertility images and the worship of the bull – all of which became part of subsequent Indian civilization. Harappan agriculture and trade Although Harappan society remained primarily based on agriculture (harvested wheat, barley, rice, peas; took meat from cattle, sheep and goats; first to domesticate chickens), trading contacts were widespread throughout the Indus Valley, as the river provided excellent means of transportation. Cotton may have been cultivated as early as 5000 BCE, and fragments of dyed cloth from around 2000 BCE suggest textile industry. Interregional contacts Harappans obtained gold, silver, copper, lead, gems from neighboring peoples in Persia (through the Khyber Pass in the Hindu Kush Mountains). Traded with Mesopotamians, mostly via watercraft along the Arabian Sea and through the Persian Gulf, as evidenced by Harappan seals on objects discovered in the Tigris-Euphrates region. Harappan decline (c. 1900-1500 BCE) Harappan civilization remains an enigma in part because we don’t fully understand why it died out … or to what extent its peoples were subsumed by subsequent Indian civilizations. Some evidence suggests the region was once much wetter and underwent a significant climate change. Other perhaps more persuasive evidence points to another cause: the courses of rivers shifted due to tectonic forces such as earthquakes, leaving the original communities no longer hospitable. In some places there’s also evidence of violence, which suggests it fell to invaders (Aryans were migrating down to India at about the same time). Sources The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History (Bulliet et al.) Traditions & Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past (Bentley & Ziegler) World History (Duiker & Spielvogel) Patterns of Interaction (McDougal Littell, publisher) AP World History review guides: The Princeton Review, Kaplan and Barron’s