Emily Dickinson Powerpoint

advertisement

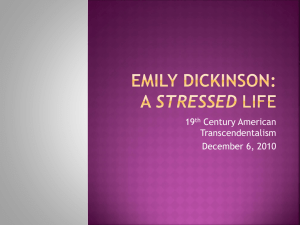

28 Emily Dickinson(1830-1886) Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Facts about Dickinson • Emily Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830 to a prominent Amherst, MA family. • Her grandfather was a leading figure in the founding of Amherst College, and her father, a lawyer, became a member of the U.S. Congress and a trustee and treasurer of the college. • Dickinson spent most of her life in Amherst in the home in which she was born. She lived with her sister Lavinia, who, like the poet, never married. • In 1847, for less than a year, Dickinson studied at South Hadley Female Seminary (Mount Holyoke). Uncomfortable with the religious orientation and severity of the institution, she returned to Amherst, leaving only for brief visits to Washington, Philadelphia, and Boston. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Facts about Dickinson • Dickinson’s father has been considered a strict, authoritarian moralist, but he was perhaps no more so than others in his time or in the conservative community of Amherst. Her mother was distant and her brother Austin could be overbearing, but ineffectively so. • Dickinson formed a friendship with Ben Newton who lived with her family as a law apprentice. • Newton, nine years older, introduced Dickinson to new literary works and new ideas concerning nature. • Newton died in 1853 from tuberculosis after having begun his law practice in another town. • In 1854, Dickinson met the Reverend Charles Wadsworth in Philadelphia while perhaps seeking spiritual guidance after Newton’s death. Wadsworth, married, visited her twice at Amherst, in 1860 and in 1880. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Facts about Dickinson • While she rarely left her home and garden and while she dressed almost exclusively in white, Dickinson had more friends than is generally acknowledged. • Dickinson was close to her brother’s wife, Susan Gilbert, and was encouraged in her writing by childhood friend and popular author Helen Hunt Jackson. She corresponded with several individuals throughout her life. • In 1862, she began a lifetime friendship and correspondence with Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a literary friend of the family. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Facts about Dickinson • Higginson advised Dickinson to write more direct and polite poetry, smoother in rhythm and rhyme. Dickinson, responding in a poem, said that although she could write like that, she chose to write poems in her own way. • Dickinson wrote the bulk of some 1775 poems between 1858 and 1864, but no more than twenty were published during her lifetime. • After Dickinson’s death in 1886, Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd edited the first three editions of Dickinson’s poetry (1890-96). • Later collections of her poetry, from 1914 on, established Dickinson’s reputation as a major poet and an important influence on American modernist poets. • Dickinson and Walt Whitman are often considered the cofounders of modern American poetry. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Issues in Dickinson’s Poetry: Dickinson’s Poetics Without reading the poem, look at “The Brain—is wider than the Sky—”: The Brain—is wider than the Sky— For—put them side by side— The one the other will contain With ease—and You—beside— The Brain is deeper than the sea For—hold them—Blue to Blue— The one the other will absorb— As Sponges—Buckets—do The Brain is just the weight of God— For—Heft them—Pound for Pound— And they will differ—if they do— As Syllable from Sound— Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 “The Brain—is wider…” continued • How does the poem look different from more conventional poems? • What do you notice about Dickinson’s punctuation? • What do you notice about her use of capitalization? • Now read the poem. • What do you notice about her rhymes? • How does she make use of the ballad stanza? Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Issues in Dickinson’s Poetry: Dickinson’s Poetics The 1890 Version versus Dickinson’s Original Well-intentioned, Higginson and Todd edited Dickinson’s poems so they would conform to standards of punctuation, capitalization, and presentation. Read the 1890 version of “The brain is wider than the sky” below and compare it to Dickinson’s version of the poem on the previous slide. Which version of the poem do you prefer? The brain is wider than the sky, For, put them side by side, The one the other will include With ease, and you beside. The brain is deeper than the sea For, hold them, blue to blue, The one the other will absorb, As sponges, buckets do. The brain is just the weight of God, For, lift them, pound for pound, And they will differ, if they do, As syllable from sound. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Issues in Dickinson’s Poetry: Dickinson’s Poetics • Most scholars find that Dickinson’s poetics reveal a unique, dramatic, authoritative, and pioneering, if not revolutionary, voice. • Most scholars believe that Dickinson’s terseness and use of irony, oxymoron, and paradox place her as much in an early modernist context as in a Romantic or realist context. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 “American poetry characteristically embodies acts of process: the Dickinsonian ‘process’ is passionate investigation. Her investigative process often implies narrative by taking speaker and reader through a sequence of rapidly changing images, even when all the action is interior. These investigations structure Dickinson’s poetry; I suspect that the flexibility of her investigative movement is the major reason why Dickinson generally was contented with common meter. She may even have enjoyed the way her condensed discoveries press against the limits of a small form.” – Helen McNeil in Emily Dickinson Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Issues in Dickinson’s Poetry: Individualism • Ralph Waldo Emerson’s influence touched almost all nineteenth-century American authors. • Dickinson’s individualism can be read as an extension of Emersonian individualism as defined in “Self-Reliance.” • Like Emerson and Thoreau in “Civil Disobedience,” Dickinson recognizes the moral authority of the individual and protests against repression of individualism. • Dickinson’s poems often concern the difficulty of maintaining individuality. A person could be declared insane or imprisoned (“Much Madness is divinest Sense”). • Consider the individualism in “The Soul selects her own Society” and the playful “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Issues in Dickinson’s Poetry: Nature • Although Dickinson’s nature poems are in the American Romantic/Transcendental tradition, her vision of nature cannot be tightly summarized. • In different poems, nature for Dickinson evokes various concepts and emotions. • Often Dickinson may use a religious imagery to express the spiritual intensity with which nature inspires her. Consider the lightly sarcastic “Some keep the Sabbath going to church.” • Other poems reflect a more secular inspiration but no less intense or life sustaining: “I taste a liquor never brewed” and “I started Early—Took my dog.” • Nature, for Dickinson, can also be complex and ambiguous. Consider “A narrow Fellow in the Grass.” Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Issues in Dickinson’s Poetry: Religion & Spirituality • Dickinson’s poetry is informed by a Christian perspective, but she rejects any church dogma or membership. In a letter to T.W. Higginson, 25 April 1962, she says that her entire family is “religious – except me.” • Her poetry suggests that Dickinson finds God in nature rather than the church. See “Some keep the Sabbath going to Church” and “I taste a liquor never brewed—.” • Dickinson’s poems about death reveal strong Christian beliefs: “I heard a Fly buzz—when I died—,” “Because I could not stop for Death—,” and “The Bustle in a House.” • Dickinson’s faith in the immortality of the soul and references to the Last Judgment are, of course, Christian. See “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers—.” Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Issues in Dickinson’s Poetry: The Search for Truth Many of Dickinson’s poems consider the search for truth from a cynical perspective. Dickinson seems to find very little truth, honesty, and integrity in human activity. Consider the following poems: • “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant” • “I died for Beauty–but was scarce” • “I like a look of Agony” • “Much Madness is divinest Sense” Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Issues in Dickinson’s Poetry: Emotional & Psychic Suffering Many of Dickinson’s poems reveal anguished and tormented speakers. Often the tone is calm, which makes the poem more chilling, and frequently the speakers imply recurring pain. Consider the following poems: • “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain” • “After great pain, a formal feeling comes—” • “One need not be a Chamber—to be Haunted—” In After Great Pain: The Inner Life of Emily Dickinson, a psychoanalytic biography, John Cody argues that Dickinson was psychologically disturbed and tormented to the point of collapse. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Issues in Dickinson’s Poetry: Marriage Dickinson never expressed personal disappointment over not marrying. She seems not only content to have not married, but also relieved. Consider “The Soul selects her own Society.” Other poems not in the text include “Of Bronze – and Blaze – ” (#290), “I cannot live with You” (#640), “She rose to His Requirement – dropt” (#732), and “I’m ‘wife’ – I’ve finished that” (#199). Dickinson’s poems can express physical passion: “Wild Nights—Wild Nights” and “I started early, took my dog,” for instance. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Key Issues in Dickinson’s Poetry: Death and Dying Many of Dickinson’s poems can be read as meditations on death and dying. Her poems seem to work out and relieve her own fears about death and dying. Death in Dickinson is often presented as a transitional state leading to a contented afterlife. Consider the following poems: • “Because I could not stop for Death—” • “The Bustle in a House” • “The last Night that She lived” • “I died for Beauty—but was scarce” Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 Reading Dickinson These key issues might suggest a narrow reading of a rather complex range of poetry, but this approach allows for – indeed, almost requires – flexibility, overlap, meanderings, and contradictions. To read Dickinson is to be engaged with an active mind, one contemplating the complexities of life. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28 For Further Consideration 1. Consider several poems of Dickinson that concern the afterlife. Do the poems express a consistent vision of the afterlife? How are they inconsistent? Among other poems, you might consider “I Heard a Fly Buzz – When I Died,” “Because I could not stop for Death,” “The Bustle in a House,” and “I died for Beauty – but was scarce.” 2. Several of Dickinson’s poems express emotional and/or psychic torment. Discuss the similarities and differences in the conditions of the speaker in several such poems. Among others, you might consider “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,” “After great pain, a formal feeling comes,” and “One Need Not Be a Chamber – To Be Haunted.” You may refer to other Dickinson poems not in the text, perhaps “There is a pain – so utter,” “We grow accustomed to the Dark,” and “Pain – has an Element of Blank.” 3. Discuss Dickinson’s use of wildlife in poems such as “Some keep the Sabbath going to Church,” “A Narrow Fellow in the Grass,” and others. What function does wildlife serve Dickinson? You may refer to Dickinson poems not in the text – perhaps “I dreaded that first Robin, so,” “A Route of Evanescence,” “Further in Summer than the Birds,” among others. Literature: Craft & Voice | Delbanco and Cheuse | Chapter 28