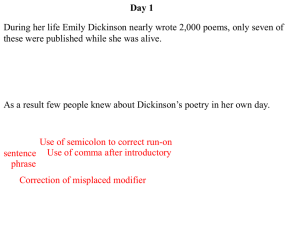

File

advertisement

BIOGRAPHY born in Amherst, Massachusetts, USA, December 10, 1830. Her quiet life was infused with a creative energy that produced almost 1800 poems and a profusion of vibrant letters. Amherst, a strict Calvinist community, 50 miles from Boston, well known as a center for Education, based around Amherst College. Her family were pillars of the local community; their house known as “The Homestead” or “Mansion” was often used as a meeting place for distinguished visitors. Emily’s father was strict and keen to bring up his children in the proper way. Emily said of her father. “his heart was pure and terrible”. At a young age, she said she wished to be the “best little girl”. However despite her attempts to please and be well thought of, she was also at the same time independently minded, and quite willing to refuse the prevailing orthodoxy’s on certain issues. EMILY AS A YOUNG WOMAN Her lively Childhood and Youth were filled with schooling, reading, explorations of nature, religious activities, significant friendships, and several key encounters with poetry. Her most intense writing years consumed the decade of her late 20s and early 30s; during that time she composed almost 1100 poems. She made few attempts to publish her work, choosing instead to share them privately with family and friends. Among her peers, Dickinson's closest friend and adviser was a woman named Susan Gilbert. In 1856, Gilbert married Dickinson's brother, William Austin Dickinson. All of the Dickinson siblings, as well as Gilbert, lived on the large Dickinson Homestead in Amherst. EMILY AND HER SECLUSION In her later Years Dickinson increasingly withdrew from public life. Her garden, her family (especially her brother’s family at The Evergreens), close friends, and health concerns occupied her. Dickinson's seclusion from 1885 onwards was probably partly due to her responsibilities as guardian of her sick mother. Scholars have also speculated that she suffered from conditions such as agoraphobia, depression and/or anxiety. It was also during this time that Dickinson was most productive as a poet, filling notebooks with verse without any awareness on the part of her family members. In her spare time, Dickinson studied botany and compiled a vast herbarium. She also maintained correspondence with a variety of contacts. One of her friendships, with Judge Otis Phillips Lord, seems to have developed into a romance before Lord's death in 1884. EMILY’S DEATH Dickinson died of kidney disease in Amherst, Massachusetts, on May 15, 1886. She is buried on the family Homestead, which is now a museum. She left precise instructions for her funeral such as the route to be taken from her house to the churchyard and the white dress she was to be laid out in. After her sister's death, Lavinia Dickinson discovered hundreds of her poems in notebooks that Emily had filled over the years. The first volume of these poems was published in 1890, with additional volumes following. A full compilation, The Poems of Emily Dickinson, wasn't published until 1955. HOWEVER… Dickinson was very eccentric in her use of punctuation and capital letters. Generally her odd use has the purpose of emphasis. After her death, Thomas Wentworth Higginson an editor, whom did not fully understand the nature of Dickinson’s talent when she was alive, had edited her poems and made some “corrections”. As a result much of her power in this unusual style was lost in the alteration. Emily Dickinson's stature as a writer soared from the first publication of her poems in their intended form. She is known for her poignant and compressed verse, which profoundly influenced the direction of 20th century poetry. The strength of her literary voice, as well as her reclusive and eccentric life, contributes to the sense of Dickinson as an indelible American character. WHAT’S SO SPECIAL ABOUT DICKINSON? 1. Explores death, morality and immortality. 2. Endings of her poems are often left open 3. Sets herself a task of definition (hope, despair, pain, joy) 4. Mixes abstract concepts and concrete details. 5. Words and issues given attention by unconventional use of capital letters and the dash. I FELT A FUNERAL IN MY BRAIN An account of the progress of a funeral from the perspective of the person in the coffin Probably written in 1861- difficult period for Dickinson as she had both religious and artistic doubts. Had a complicated and disappointed feelings for Samuel Boules (Editor of Springfield Republican Newspaper). Suggests physical and intense experience I felt a Funeral, in my Brain, And Mourners to and fro Abolishes barrier between sickness of the mind and the body. Repetition- impacts her physically Kept treading - treading - till it seemed That Sense was breaking through - And when they all were seated, A Service, like a Drum Kept beating - beating - till I thought My mind was going numb From Brain (1) to mind (8)- physical intensity lessened, becomes more psychological. However, it is thought Dickinson found no clear distinction between mind and body Repetition of “And” suggests sense of forward motion, powerless to stop The “I” becomes disorientated, boundary between internal and external collapses. The last two stanzas maybe seen as if the speaker is entering death. And then I heard them lift a Box And creak across my Soul With those same Boots of Lead, again, Then Space - began to toll, Marks time- decisive moment As all the Heavens were a Bell, Reduced to just hearing as sound fills the room And Being, but an Ear, And I, and Silence, some strange Race, Wrecked, solitary, here - Sense of Isolation- shipwrecked from life. Cut-off alon with silence and left “here”. Startling immediacy to thi moment Poem is moving And then a Plank in Reason, broke, again And I dropped down, and down And hit a World, at every plunge, “Plank” (image of grave) in “Reason” did not hold up- cannot make sense And Finished knowing - then - “I”, a new experience- new levels, new worlds, to finish “knowing”. What does Dickinson “know”? “KNOWING” oPoets knowledge is beyond finished oSpeaker has finished imagined funeral with the knowledge of something she cannot express oKnowledge itself is finished oDickinson's desire to experience death- beyond the imaginations capacity to do so oOr…. Is this poem just a narrative of a nightmarish, terrifying experience? I HEARD A FLY BUZZWHEN I DIEDThis poem can be compared to “I felt a funeral in my brain” as it also explores the transition between life and death. Written in the past tense, in the voice of the dying person, and describes the moment of death. It is important to note that in the Calvinist’s tradition, the moment of death is the moment when the soul faces God’s judgment. I heard a Fly buzz - when I died The Stillness in the Room Was like the Stillness in the Air Between the Heaves of Storm The Eyes around - had wrung them dry And Breaths were gathering firm For that last Onset - when the King Be witnessed - in the Room I willed my Keepsakes - Signed away What portion of me be Assignable - and then it was There interposed a Fly With Blue - uncertain - stumbling Buzz Between the light - and me And then the Windows failed - and then I could not see to see - The startling perspective is announced- the speaker is the person dying. The moment is dominated by the buzzing of a fly in the death-room. I heard a Fly buzz - when I died Use of dashes and run on lines take away from the sing-song effect of the hymn form. Instead they get the reader to slow down, providing emphasis. The Stillness in the Room Was like the Stillness in the Air Between the Heaves of Storm - The Eyes around - had wrung them dry And Breaths were gathering firm For that last Onset - when the King Be witnessed - in the Room - As death approaches, the mourners gather and wait for the moment when their “King” or God gives judgment. “Be witness”- they are filled with expectancy. Speaker has tidied up her legal affairs and waits for the moment of death I willed my Keepsakes - Signed away What portion of me be Assignable - and then it was There interposed a Fly Arrival of a fly might suggest human decay and corruption- is Dickinson trying to tell us that death cannot be managed, arranged or ordered. With Blue - uncertain - stumbling Buzz Between the light - and me And then the Windows failed - and then I could not see to see - The stumbling, buzzing fly comes between the dying person’s sight and source of light. The buzzing fly suggest life is a comedy rather than a tragedy. The buzzing is unexpected, like a drunkard disturbing the solemnity of an important occasion. Images of light and darkness- speaker is plunged into the darkness of death and the moment has passed I HEARD A FLY BUZZWHEN I DIEDThe ending of the poem, and the anti-climax it describes, suggests that humans have no way of knowing if the immortal life with God, that their faith actually professes, actually exists. “I could not see to see-”: is this the message of the poem that after dying all is darkness and emptiness? Is that the significance of the dash that ends the poem? This may offer evidence of Dickinson’s lack of faith in the afterlife with God. "Hope" is the thing with feathers— That perches in the soul— And sings the tune without the words— And never stops—at all— And sweetest—in the Gale—is heard— And sore must be the storm— That could abash the little Bird That kept so many warm— I've heard it in the chillest land— And on the strangest Sea— Yet, never, in Extremity, It asked a crumb—of Me. Written in 1861 ( same as “I Felt…” and “I heard…”) after a difficult period in her life, Dickinson becomes optimistic and reveals a cheerful, resilient mood. Use of physical features to DEFINE an abstract experience. (One of her definition poems) Although the poem consists of a series of comparisons, Dickinson does not use the word “like”. Hope is not “like” a thing with feathers, it IS the thing with feathers. Her direct and confident statements make her definition vivid and immediate. Like religious symbolism, Hope is imagined as having some of the characteristics of a bird. Use of metaphors, does not DEFINITION POEM: PHYSICAL use “like”- a sense of Hope- some DETAILS DEFINING THE comparisons characteristics of a ABSTRACT bird. It can fly and lift First line is a confident and direct statement- vivid and immediate the spirit. Feathers are warm and comforting Hope resides in the soul "Hope" is the thing with feathers— That perches in the soul— And sings the tune without the words— And never stops—at all— And sweetest—in the Gale—is heard— And sore must be the storm— That could abash the little Bird That kept so many warm— The song Hope sings is beyond logic, reason and our own limitations. It is resilient and unceasing In times of distress and uncertainty, Hope may seam but a “little bird” i.e. it may seem slight but it is powerful and can comfort many LAST STANZA OUTLINES DICKINSON’S PERSONAL EXPERIENCE OF HOPE IN TIMES OF HER OWN ANGUISH I've heard it in the chillest land— And on the strangest Sea— Yet, never, in Extremity, It asked a crumb—of Me. Hope has offered comfort and has asked nothing in return. Hope is generous and others-seeking. The last stanza is a solemn note as it gives Hope the dignified celebration it deserves. Form: Sing song nature is achieved with half rhymes, enjambment (run-on-lines), repetition and alliteration THERE’S A CERTAIN SLANT OF LIGHT This poem explores a state of mind in which the comfort of hope is absent. In its place there is despair which she associates with a certain kind of winter light falling on the landscape. The poem was probably written 1861 (like the other three poems we have studied) during which she suffered a major personal crisis. The speaker sees the light as an affliction, affecting the inner landscape of the soul. There's a certain Slant of light, Winter Afternoons – That oppresses, like the Heft Of Cathedral Tunes – Heavenly Hurt, it gives us – We can find no scar, But internal difference, Where the Meanings, are – None may teach it – Any – 'Tis the Seal Despair – An imperial affliction Sent us of the Air – When it comes, the Landscape listens – Shadows – hold their breath – When it goes, 'tis like the Distance On the look of Death – THERE'S A CERTAIN SLANT OF LIGHT Striking simile: Winter and There's a certain Slant of light, Winter Afternoons – That oppresses, like the Heft Of Cathedral Tunes – Heavenly Hurt, it gives us – We can find no scar, But internal difference, Where the Meanings, are – church music depicts the heaviness of the soul. The light is oppressive on the speaker. The image becomes music- Dickinson blurs the senses (synesthesia) which creates a feeling of disturbance. No physical wounds but affects her inner life/ soul and brings despair. One could say she is suggesting a relationship between Heaven and humanity. Heaven seems to be cruel to humanity. THERE'S A CERTAIN SLANT OF LIGHT Seal: Royal stamp/ Closed communication, Authoritative style. “Tis”- the slant of light is a sign of despair- both a psychological and a spiritual condition The Hurt in stanza 2 cannot be explained, it is without remedy. None may teach it – Any – 'Tis the Seal Despair – An imperial affliction Sent us of the Air – Movement from inner landscape to external one “Seal” and “Imperial”: message is sent by a higher authority. Message: Human mortality beyond contradiction? When it comes, the Landscape listens – Shadows – hold their breath – When it goes, 'tis like the Distance On the look of Death – Dash= The unknown into which we all face. Light causes the world to be still and hushed. Passing of the light does not lift the feeling of despair but in fact leaves a chill- Distance is seen between present and death. First published anonymously in 1861 where two lines were altered by the editor to achieve an exact rhyme and another was changed to make the meaning clearer. Central metaphor of the poem is intoxication. This is ironic because Dickinson grew up in a puritan household and her father was a supporter of abstinence from alcohol. It is also ironic that Dickinson chose to write this poem in the common rhythm of hymns. The poem is about nature and how experiencing it is so wonderful and intoxicating that it's like being drunk. I taste a liquor never brewed – From Tankards scooped in Pearl – Not all the Frankfort Berries Yield such an Alcohol! Inebriate of air – am I – And Debauchee of Dew – Reeling – thro' endless summer days – From inns of molten Blue – When "Landlords" turn the drunken Bee Out of the Foxglove's door – When Butterflies – renounce their "drams" – I shall but drink the more! Till Seraphs swing their snowy Hats – And Saints – to windows run – To see the little Tippler Leaning against the – Sun! I taste a liquor never brewed – From Tankards scooped in Pearl – Not all the Frankfort Berries An exaggerated playful tone is established from the first line. Liquor tastes of something never existed before- of nature Yield such an Alcohol! Inebriate of air – am I – Celebrates the joy of excess, a reckless, indulgent joy And Debauchee of Dew – Reeling – thro' endless summer days – From inns of molten Blue – Central metaphor: intoxication brought on by a joyous appreciation of life. The poem describes the speaker’s sense of delight in the beauty of the world around her. The extravagant imagery captures the mood of dizzy happiness that infuses the poem. Images of flowers as inns or taverns and bees as drunkards gives the poem a sense of cartoon humour. When "Landlords" turn the drunken Bee Last stanza: does not Out of the Foxglove's door – show the world’s beauty as a sign of When Butterflies – renounce their "drams" – God’s creativity. The inhabitants of heaven I shall but drink the more! are presented as faintly ridiculous, enclosed and maybe envious of freedom Till Seraphs swing their snowy Hats – and of the “little Tippler”. And Saints – to windows run“leans – against the- Sun-”- Comic rebelliousness? Applauded by the To see the little Tippler angels as they swing their hats to honour her? Leaning against the – Sun! OR some Christian’s believe the “Sun” is a symbol of Christ. The speaker maybe announcing their intention to enjoy the beauty of the world until they come into the AFTER GREAT PAIN A FORMAL FEELING COMES• Written in 1862, some critics believe she was on the edge of madness at the time. • There is an absence of personal statement which gives the poem a universal quality, as if the poet is speaking for all who have suffered great pain. The experience is one that all of us will undoubtedly endure at some time or other and may be one you have already endured. • Dickinson brilliantly recreates the suffering we undergo after some terrible, excruciating event in our lives. The specific cause of the torment in this poem does not matter; whatever the cause, the response is the same, and, in this poem, the response is what matters. • She traces the numbness experienced after some terrible blow. Is numbness one way we protect ourselves against the onrush of pain and against being overwhelmed by suffering? She is discussing emotional pain, but don't we respond similarly to a physical blow with numbness before pain sets in? After great pain a formal feeling comesThe nerves sit ceremonious like TombsThe stiff Heart questions was it He, that bore, And Yesterday-or Centuries before? The Feet, mechanical, go roundOf Ground, or Air, or OughtA Wooden way Regardless grown, A Quartz contentment, like a stoneThis is the Hour of LeadRemembered, if outlived, As Freezing persons, recollect the SnowFirst- Chill- then Stupor- then the letting go- Not properly described- Why not? After great pain a formal feeling comesThe nerves sit ceremonious like TombsThe stiff Heart questions was it He, that bore, And Yesterday-or Centuries before? The Feet, mechanical, go roundOf Ground, or Air, or OughtWooden way Regardless grown, A Quartz contentment, like a stone- This pain does not lead to a loss of control but control of formality. Long sentences in stanza one are pleasant Contrasting with stanza one, a disjointed movement is formed in stanza 2 with unconnected sensations and thoughts. This reflects the mind’s ability to make sense of experience and derive meaning from it. Pain results in hard, stone like insensitivity which brings its own kind of contentment. The word “contentment” seems ironic. Nature of contentment is explainedheavy, deadening oppression when all human sensations become frozen. This is the Hour of LeadThis is not forgotten even if they survive it. Remembered, if outlived, As Freezing persons, recollect the SnowFirst- Chill- then Stupor- then the letting goThe experience is likened to that of a person freezing in snow. The thoughts are again incomplete. Has the freezing person survived this ordeal or does the experience continue? I COULD BRING YOU JEWELHAD I A MIND TO• Although Dickinson was a recluse, she had a wide circle of friends to whom she wrote many letters. • Many of her letters took the form of poems, or were written to accompany small gifts that she enclosed. • These poems, many of them written as riddles, show the playful and humorous sides of Dickinson’s personality. • It is thought that this poem was intended as a token of her love although she took considerable pains to disguise the identity of her beloved. • One of her most joyful poems. I COULD BRING YOU JEWELS--HAD I A MIND TO-I could bring You Jewels--had I a mind to-But You have enough--of those-I could bring You Odors from St. Domingo-Colors--from Vera Cruz-Berries of Bahamas--have I-But this little Blaze Flickering to itself--in the Meadow-Suits Me--more than those-Never a Fellow matched this Topaz-And his Emerald Swing-Dower itself--for Bobadilo-Better--Could I bring! I could bring You Jewels--had I a mind to-But You have enough--of those-I could bring You Odors from St. Domingo-Colours--from Vera Cruz-Berries of Bahamas--have I-But this little Blaze Flickering to itself--in the Meadow-Suits Me--more than those-- This gift gives the speaker a note of confidence and self-ease . It is worth noting the first stanza contains luxurious, exotic gifts which is reflected in the long lines. However, Dickinson employs shorter lines when she settles on her chosen gift which reflects her tone becoming more decisive. The opening line of the poem strikes a note of confidence and playfulness, which is sustained to the end of the poem. There is a conversational feel to the opening lines, achieved by the length of the line and the phrase “had I a mind to”. This is Dickinson at her most relaxed. THE FIRST TWO STANZAS THE SPEAKER CONSIDERS THE GIFT SHE WILL OFFER HER BELOVED, THE “YOU” OF THE POEM. SHE SETTLES ON A SMALL MEADOW FLOWER. THE CHOSEN GIFT IS A MARK OF THE SPEAKER’S FREEDOM AND UNIQUENESS, AND A REFLECTION, PERHAPS, OF HER UNSHOWY PERSONALITY. Never a Fellow matched this Topaz-And his Emerald Swing-Dower itself--for Bobadilo-Better--Could I bring! THE CONCLUDING RHETORICAL QUESTION SUGGESTS THAT THE FLOWER IS THE BEST GIFT SHE COULD OFFER. In its playful, assured way, the poem establishes that the true value of gifts and the true nature of riches cannot be measured in material terms. A jaunty confident tone is evident in the use of the word “fellow”. Notice how, in this final stanza, the assured, confident tone is emphasized in the use of the word “Never” and in rhyming of “Swing” and “bring”, which closes her argument with a ring of authority. FORM OF POEM Dickinson employs a four line stanza with the rhyme occurring between lines 2 and 4. Unlike other of her poems, there is a conversational feel to the opening lines, achieved by the length of the line and the phrase “had I a mind to”. This is Dickinson at her most relaxed. As the poem proceeds, the tone becomes less conversational and concludes with the magisterial four word last line.