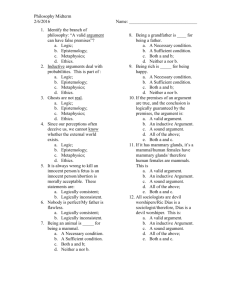

Workshop on Logic PowerPoints

advertisement

Lawyers, Logic, and Logical Fallacies Profs. Streitz & Crouse Deductive Logic Forms • Valid: if the premises are true then the conclusion is necessarily true • Sound: if the form is valid and the premises are in fact true Modus Ponens “the way or mode of positing” Modus Ponens • 1. If A, then B 2. A. 3. B • Example: 1. If Lassie is a Collie, then Lassie is a dog. 2. Lassie is a Collie So, 3. Lassie is a dog. Modus Ponens • Lines 1 and 2 are the premises, and line 3 is the conclusion. • Line 1 is the major premise. • Line 2 the minor premise. Modus Ponens • For our purposes, the major premise is usually a rule of law (cReac) • The minor premise is a factual claim (creAc) Hypothetical 1 Fraud 1.Misrepresentation 2.Scienter 3.Reliance 4.Justifiable (Reliance) 5.Damages Answer? Δ • If O then ~J • O • ~J Π • If SO then J • SO • J Formal Fallacy: Affirming the Consequent • 1. If A, then B 2. B 3. A • While the premises may both be true, they do not guarantee the conclusion. Formal Fallacy: Affirming the Consequent • 1. If SO, then J 2. J 3. SO Modus Tollens “the way that denies by denying” Modus Tollens • 1. If A, then B. 2. Not B. 3. Not A. • Example: 1. If it is snowing, then the ground is white. 2. The ground is not white. So, 3. It is not snowing. Hypothetical 2 Slander 1.Defamatory Statement 2.About the Plaintiff 3.Verbal Publication 4.Damages Answer? Δ • If D then PL • ~PL • ~D Π • If SPS then D • SPS • D Formal Fallacy: Denying the Antecedent • 1. If A, then B 2. Not A 3. Not B • While the premises may both be true, they do not guarantee the conclusion. Formal Fallacy: Denying the Antecedent • 1. If D, then PL 2. ~D 3. ~PL Disjunctive Syllogism Disjunctive Syllogism • Disjunctions are statements of the form "Either A or B". The parts of a disjunction are called disjuncts. Disjunctive Syllogism • 1. Either A or B 2. Not A. So, 3. B • Example: Either Atlanta is a state or Atlanta is a city. Atlanta is not a state. So, Atlanta is a city. Hypothetical Syllogism Hypothetical Syllogism • 1. If A, then B. 2. If B, then C. 3. If A, then C. • Hypothetical syllogism is one of the proof rules in classical logic, and is a valid argument form. This kind of argument states that if one implies another, and that other implies a third, then the first implies the third. Hypothetical Syllogism • The argument form is called hypothetical syllogism because it involves only hypothetical (if-then) statements. Every argument that exemplifies this form is a valid one. • Note that contrary to many definitions of deductive reasoning, this is not reasoning from the general to the particular. • In legal reasoning, this form is often coupled with modus ponens to create a more complex argument. Hypothetical Syllogism • Example: • If defendant’s counsel sleeps for a long time at trial, then counsel has slept through a significant portion of trial • If counsel has slept through a significant portion of trial, defendant’s 6th Amendment right to counsel has been violated • Therefore, if defendant’s counsel sleeps for a long time at trial, defendant’s 6th Amendment right to counsel has been violated. Informal or Non-Deductive Arguments • • • • • Analogical Inductive Conductive Abductive Seductive – just kidding Analogical • A claim that two or more things that are similar to each other in some respect(s) are also similar (or should be treated similarly) in other respects. Analogical • In a legal argument, an analogy may be used when there is no precedent on point. • Reasoning by analogy often involves referring to another case that concerns similar facts and legal principles. Inductive • A statistical syllogism is an example of inductive reasoning: • 90% of humans are right-handed. • Joe is a human. • Therefore, the probability that Joe is right-handed is 90%. • A stronger example: • 100% of life forms that we know of depend on liquid water to exist. Therefore, if we discover a new life form it will probably depend on liquid water to exist. Inductive • Inductive Arguments in Law? Abuctive • Reasoning to the best explanation • What detectives do (and Sherlock Holmes mislabeled as “deductive”). • Abductive reasoning in law? Conductive • Cumulation of consideration or balance of consideration arguments. • Example: (1) I will take the job in Chicago, because (2) people are nice there, (3) the pay is good, (4) the infrastructure is good there, (5) I have friends there, (6) the working hours are reasonable, and (7) the public transport system is great. But (8) beer is overpriced. Conductive • Conductive reasoning in Law? • Balancing Tests • Example: FRE 403 allows the court to exclude relevant evidence if its "probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, misleading the jury, or by considerations of undue delay, waste of time, or needless presentation of cumulative evidence.” Informal Fallacies What are fallacies? • Fallacies are defects that weaken arguments. • By learning to spot them, you can strengthen your ability to evaluate the arguments you make, read, and hear. • It is important to realize two things about fallacies: • First, fallacious arguments are very common and can be persuasive, at least to the casual reader or listener. Great for juries, but not appellate judges (or legal writing instructors). • Second, it is sometimes hard to evaluate whether an argument is fallacious. Fallaciousness (is that a word? fallaciosity?) comes in degrees, and may depend on context. Appeal to Authority • Often we add strength to our arguments by referring to respected sources or authorities and explaining their positions on the issues we're discussing. If, however, we try to get readers to agree with us simply by impressing them with a famous name or by appealing to a supposed authority who really isn't much of an expert, we commit the fallacy of appeal to authority. Appeal to Authority • To philosophers or theologians: a fallacy, the seriousness of which is measured by the reliability of the authority. An appeal to anyone less than God or anything less than the Platonic forms of truth or beauty is suspect. Appeal to Authority • To lawyers: a slam-dunk, inyour-face, nanny-nanny-boo-boo, I-win-you-lose argument. The gold standard. As long as it is binding authority. Appeal to Pity • Definition: The appeal to pity takes place when an arguer tries to get people to accept a conclusion by making them feel sorry for someone. Appeal to Pity • Who is your audience? – Philosophers: don’t do it – Judges: you’d better be subtle – Juries: have at it? Hasty Generalization • Definition: Making assumptions about a whole group or range of cases based on a sample that is inadequate (usually because it is atypical or too small). • Stereotypes about people or entities (e.g., “corporations put profits over people”). Hasty Generalization • Example: I have seen 208 shirtless men in the last year. 203 of them committed felonies. The vast majority of men without shirts are felons. Hasty Generalization • Problem: My sample was 43 reruns of the TV show Cops. Probably an atypical sampling of American males. • I still think my conclusion is warranted. Begging the Question • A complicated fallacy; it comes in several forms and can be harder to detect than many of the other fallacies we've discussed. • Basically, an argument that begs the question asks the reader to simply accept the conclusion without providing real evidence • The argument either relies on a premise that says the same thing as the conclusion (which you might hear referred to as "being circular" or "circular reasoning"), or simply ignores an important (but questionable) assumption that the argument rests on. Begging the question “The defendant’s conduct was reckless because he recklessly caused the accident by driving too fast.” Begging the question • Pet peeve: misusing the phrase “begs the question.” • Please, don’t ever say that something that raises a question “begs the question.”