Death and Dying Presentation

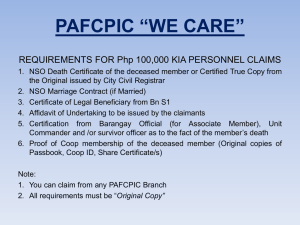

advertisement

Many of the central themes found within Buddhist thought can be clearly seen when looking at Buddhist attitudes towards death and dying. These include: • Saṃsāra • The three marks of existence • Karma Also, looking at death within Buddhism can provide an insight into how modern Buddhists practice across the world. Saṃsāra • All unenlightened beings are in a perpetual cycle of life death and rebirth known as saṃsāra. • Saṃsāric existence is conditioned by three marks: impermanence (anitya/ anicca), not-Self (anātman/ anattā), and dis-ease (duḥkha/dukkha). • The teaching of anātman outlines that there is nothing that has a permanent Self, there is no underlying consciousness or sense of person that is carried from life to life. Karma • Karma is an system of cause and effect in which all intentional actions generate a karmic result. • Wholesome actions bring about good karmic results whereas unwholesome actions will bring about unpleasant karmic results. • Karmic results are not necessarily immediate, they can take several lifetimes to come into fruition. • The quality of an individual’s death and rebirth is also influenced by their karma. Dependent Origination • Dependent Origination is a Buddhist doctrine of causality. • Everything within saṃsāra is caused into existence, which in turn causes something else into existence. • This is useful in understanding how rebirth works. When a person is alive they accumulate good and bad deeds. The resulting karma does not simply disappear at death. Instead, due to the remaining karmic seeds a new being is caused into existence so that remaining karmic results may take place. • In Buddhist cultures it is believed that a good death is one in which the individual is conscious and aware of what is happening to them. • The last moments of life can affect the nature of rebirth. The more calm and prepared a person is the better their rebirth is considered to be. • The last thoughts of an individual will shape their future rebirth, this moment itself being dictated by prior karma. • In most forms of Buddhism it is believed that death occurs after the last breath has been taken. What happens to an individual after they have died is not agreed upon within Buddhist thought. • In Tibetan Buddhism, after the last breath is taken, the individual is in an intermediate state between their previous life and their new life. This state, known as the bardo can last up to 49 days. • In Theravāda Buddhist doctrine rebirth is immediate. However, customs and rituals in Theravāda countries such as Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Laos suggest that in practice most Buddhists believe in some forms of intermediate state of up to seven days. • Within Buddhist practice there are no last rites that must be performed. • If the family choose to do so there are certain acts that are understood to help the deceased. Chanting texts, including pirit, will generate merit that can be transferred to the deceased. • A request for the refuges and precepts can be made. This can be done in Pali, the scriptural language of Theravada Buddhism, Tibetan, Chinese, Japanese or in English. There can be a homage paid to the Buddha, this would be repeated three times. There could be verses from Tibetan, Mahayana and Theravada literature depending upon the tradition of the deceased. • Offering of cloth of the dead (mataka-vastra-puja) • This ritual is found within Theravāda cultures. Before a funeral monks are offered a white cloth which is intended to be used to make monastic robes. This ritual is used to generate merit for the deceased. During this ceremony, the following from the Mahaparinibbana Sutta is recited: Formations truly they are transient, It is their nature to arise and cease, Having arisen, then they pass away, Their calming and cessation—happiness. This is a white cloth that was offered to monks as part of the matakavastra-puja at a funeral in Laos (2007). • Water is then poured into an overflowing cup to represent the transfer of merit whilst the following is chanted: Just as water rained on high ground moves to the low land, even so does what is given here benefit the dead. Just as the rivers full of water fill the ocean full, even so does what is given here benefit the dead. The above verses have been translated for this document, or have been adapted from ‘The Mirror of the Dhamma’ which can be found at www.bps.lk/olib/wh/wh054.pdf Ghost Month (China) In China there are a number of rituals that are performed in memory of the dead during the course of the ghost month. During this period the ‘spirits’ of the dead are invited to the Buddhist monasteries to participate. One of the most important aspects is the recitation of the name Amitābha or the scripture of the Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha. This generates merit which can then be transferred to the dead. Offerings of food and incense are made to the buddhas whilst lists of the dead are read by monks to ensure that they share in the merit. The climax of the Ghost Month rituals is the offering of food and vast amounts of paper money to the hungry ghosts and abandoned ‘souls’ and the transfer of the resulting merit to the deceased. At the start of the Chinese Ghost Month laypeople buy yellow paper slips, called ‘lotus seats’, to be displayed in a hall in the monastery temporarily known as the ‘Hall of Rebirth’. The ‘lotus seats’ state the name of the person who bought it and the name of the being to whom it is dedicated. At the end of the Ghost Month they are burned along with the paper money. Ghost Month (Laos) In Laos there are two annual festivals for the deceased, both take place during the ninth lunar month. The ‘festival of rice packets decorating the earth’ is held on the first day of the new moon, and the ‘festival of baskets drawn by lot’ takes place at full moon. Both rituals are occasions for caring for deceased relatives, ghosts and agricultural divinities by transferring food and merit to them. In the former the lay people leave packets of rice wrapped in banana leaves around the temple as offerings to ghosts and the dead. The second festival is an occasion for remembering ancestors. Laypeople prepare baskets filled with offerings, including food, plants and flowers, for their deceased relatives. A paper slip on the basket states who it is from and who it is intended for. The baskets are brought to the temple and assigned by lot to specific monks who then ‘transfer’ the baskets to the deceased relatives. People also make offerings to their ancestors at small shrines containing the relics of their bones collected after cremation.