Reading the Bible as Literature

advertisement

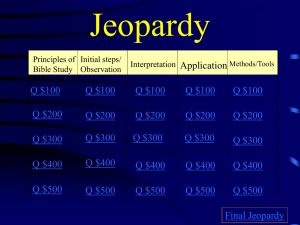

Preface Reading in a Special Way Reading the Bible as literature boils down to a certain way of reading—reading in the context of the categories and disciplines of literature—to better understand or to cast light upon its words; it means understanding the features that make the Bible literature without denying its special role as religious or sacred text. Two Collections The Bible commonly has been understood as made up of two sets of texts, the Hebraic and Christian: the “Old Testament,” sometimes referred to as the Hebrew Bible (this, more accurately referring to a collection written in the original Hebrew language), and the Christian “New Testament,” used here without any suggestion that the Old Testament depends upon the New for its meaning. Both texts may belong within their own respective traditions. Translation The translation used will be the New Revised Standard Version, a translation, one that describes itself as going back to the King James Version and as retaining much of the original languages (Hebrew and Greek) while making them accessible to modern readers. This translation provides extensive study notes, timelines, graphs, charts, maps, and outlines that will aid readers in understanding the Bible in the context of its own history, culture, and literature, and will help readers avoid reading anachronistically. Beyond Sacred Book Reading the Bible “as literature” redirects readers from issues concerning the sacred nature and authority of the Bible to its existence as literature of a particular people: the literature of the Hebrew nation (the Old Testament), and the literature of Christianity (New Testament). With its complex history of composition, the writing of the Old Testament alone taking over a thousand years, the Bible contains much that is unique to itself but shares the mythological, metaphorical, and symbolic language that belongs to literature across the centuries. Written in poetry and prose, much of the Bible reads as a structured narrative abounding in stories, characters, and plots worked out against a backdrop of an ancient people trying to understand its nature, destiny, and place in the universe. Northrop Frye, Words with Power Being a Second Study of The Bible and Literature (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1990) xiii describes the central structural principles of literature as deriving from myth, giving it “its communicating power across the centuries” and a “continuity of form that points to an identity of the literary organism.” Basic Aim of Text The more basic and immediate aim of this text is to introduce readers to some of the common tools of literary analysis, to call attention to close reading in context, to stress the role of interpretation, and finally, as an outcome of reading and understanding, to appreciate the Bible. Emphasizing unity, coherence, and whole-part relationships, and the diversity among the texts themselves, this text invites readers to look at the Bible (and the books in the Bible), as it exists, as a whole. It pays attention primarily to literary elements in the text but presents other information important to building a context for understanding the Bible and for encouraging further study. Organization Chapters for this text have been organized to demonstrate how authors use language in particular ways to represent and create meaning; how major genres begin with authors’ seeing, picturing, imitating, and creating literature that illuminates actual life; how characters reveal identities; and how themes help to create a sense of the Bible as a book. These literary activities—using language in particular ways, discovering meaning through language, and the acts of seeing, classifying, identifying, and unifying—suggest an active rather than passive interaction with the material and point to the requirement of literature that readers engage with the primary text.