A-is-for

advertisement

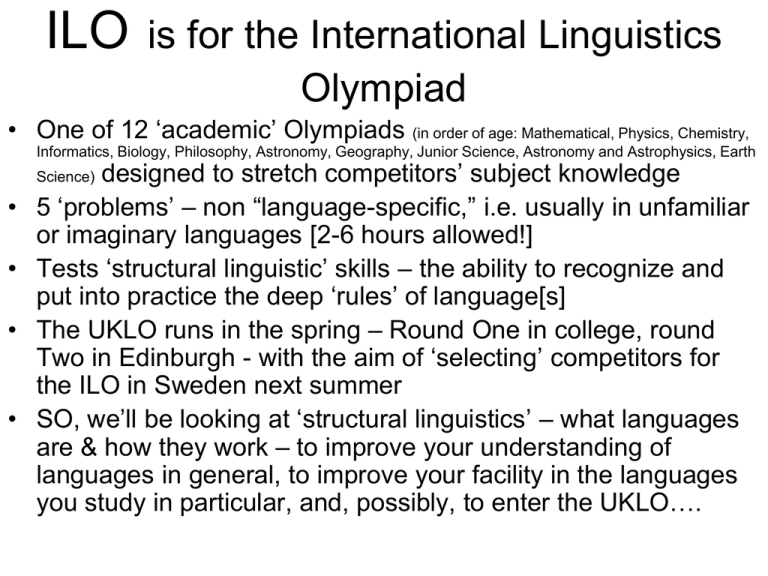

ILO is for the International Linguistics Olympiad • One of 12 ‘academic’ Olympiads (in order of age: Mathematical, Physics, Chemistry, Informatics, Biology, Philosophy, Astronomy, Geography, Junior Science, Astronomy and Astrophysics, Earth designed to stretch competitors’ subject knowledge 5 ‘problems’ – non “language-specific,” i.e. usually in unfamiliar or imaginary languages [2-6 hours allowed!] Tests ‘structural linguistic’ skills – the ability to recognize and put into practice the deep ‘rules’ of language[s] The UKLO runs in the spring – Round One in college, round Two in Edinburgh - with the aim of ‘selecting’ competitors for the ILO in Sweden next summer SO, we’ll be looking at ‘structural linguistics’ – what languages are & how they work – to improve your understanding of languages in general, to improve your facility in the languages you study in particular, and, possibly, to enter the UKLO…. Science) • • • • A is for Apple, Arbitrariness & Ox • Why is ‘A’ for ‘Apple’? • What is ‘apple’ in other languages? • So, what is the relationship between ‘A’ and ‘apple’? • For linguists, a word is a signifier • What does ‘apple’ signify? That is, what do you think when you think ‘apple’? A is for Apple, Arbitrariness & Ox • For linguists, what you think of when you think of a word is its signified [not a thing, but an idea of a thing…] • The first principle of linguistics is [according to Saussure, who started it!] ‘the arbitrariness of the sign’ - that is, the ‘arbitrariness of the relationship between the signifier and the signified’ • Meaning? Well, meaning that we could choose ANY word to refer to ANY thing… (As long as we all agreed) A is for Apple, Arbitrariness & Ox • WHAT we all need to agree on are the ‘rules’ – HOW we are going to organise our language… • So a language is a rule-governed system of relationships between signifiers • ‘A green apple’ – what is the rule for adjectival modification in English? • …and in other languages? A is for Apple, Arbitrariness & Ox • What is ‘A’ ‘for’ in other languages? • In the Phoenician alphabet, from which ours ultimately derives, the ‘A’ was ‘for’ the head of an ox … • The ‘alphabet’ thus begins as a pictographic system, before becoming a symbolic system… • Cattle were common in Egypt, where Phoenician originated, just as apples were common in medieval England: • Agreed signifieds for agreed signifiers… A is for Apple, Arbitrariness & Ox • If a word [or a letter, or a sound…] is a signifier and • What the word refers to is its signified • Then, using a word to refer to something is a signification • For Saussurian or ‘structural’ linguists, the only useful definition of a language is ‘a system of shared significations’ • When you work out the system, you work out the language… What’s the system… • … of symbol/letter correspondence here? bx’tt wx bxsx Or here? pbx’tt gxfxs wx dx R is for Regularity, Roots & recognition • What does it mean when we say that a language, or a linguistic form, is regular? “I love to skink.” • When we acquire a language, what we acquire is the ability to recognise & reproduce its regular patterns If “skink” is a regular verb, what form does it take in the following…? 1. “He ……….. for a living!” 2. “They’ve tried …………., and they didn’t like it.” How many regular forms could “skink” take in the following…? 3. “John & Julie ………….. for the first time yesterday.” 4. “He has ……………, but won’t do it again!” How would you describe the ‘rule’ in each example? R is for Regularity, Roots & recognition •“skink” is a morpheme - a ‘base unit’ or ‘root form’ or ‘brick’ that cannot be meaningfully divided into smaller units [or forms or bricks] – all languages are systems of relationships between morphemes •Because it is free to stand alone, linguists call it a free morpheme. •Because alterations to its form would produce an alteration to its meaning, linguists call it a semantic morpheme. •The additional ‘s,’ ‘ing,’ ‘ed’ in ‘skinks,’ ‘skinking,’ ‘skinked’ need to be bound on to something to work, so each is a bound morpheme. •Because changing which one of these is ‘bound’ to any free morpheme modifies the grammatical tense or number, linguists call each a grammatical morpheme. R is for Regularity, Roots & recognition • Morphemically, nouns are also ‘regular’ or ‘irregular’: • Which ONE noun could be modified by having ALL of the following morphemes bound to it? Note down your answers to EACH and why they reduce as you go along… • “step……..” • “grand…….” • “……less” • “……ly” • “……board” • “……ship” • Which of these morphemes are grammatical/bound, and which semantic/free? • How does each of the grammatical morphemes modify the semantic morpheme “mother”? R is for Regularity, Roots & recognition • What would you know about a noun to which the following morphemes could be bound…? 1. “step……..,” AND “grand……..”? 2. “……free,” AND “…..rich”? …what’s the system here? [A Drehu/English problem from the 2008 Linguistics Olympiad!] drai-hmitrötr gaa-hmitrötr i-drai i-jun i-wahnawa jun ngöne-gejë ngöne-uma nyine-thin uma-hmitrötr sanctuary [holy place] bunch of bananas calendar bone church coast awl [a tool for making holes] Sunday skeleton wall (an Austronesian language with about 12,000 speakers on Lifou Island, New Caledonia.) The solution • The REGULAR PATTERN = the modifying morpheme, follows its semantic morpheme or head. • • • • • • • • • • drai-hmitrötr = Sunday (holy day) gaa-hmitrötr = sanctuary (holy place) uma-hmitrötr = church (holy house) ngöne-uma = wall (house border) ngöne-gejë = coast (water border) nyine-thin = awl (tool to poke) jun = bone i-jun = skeleton (multitude of bones) i-wahnawa = bunch of bananas (multitude of bananas) i-drai = calendar (multitude of days) C is for Carroll & Chomsky • PRINCIPLE 1: arbitrariness - Saussure points out that all linguistic units are arbitrary (there is no necessary connection between any signifier & any signified) • PRINCIPLE 2: regularisation - Chomsky points out that when we acquire a language, what we acquire are the ‘principles’ or ‘rules’ of the language as well as the arbitrary symbols to which they apply • Meaning? Meaning that whenever you look at a word or phrase, your mind instantly searches for its ‘rules’ in order to make sense of it C is for Carroll & Chomsky • Before Saussure, & long before Chomsky, Lewis Carroll wrote Jabberwocky: "Beware the Jabberwock, my son! The jaws that bite, the claws that catch! Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun The frumious Bandersnatch!“ 1. What do you know about ‘Jabberwock’? How? [what rules identify it?] 1. What do you know about ‘frumious’? How? [what rules identify it?] 1. What do you know about ‘Jubjub’? How? [what rules identify it?] • • • • • • • • • • • Am I dantier than I am cloovy? (a problem from the NALCO 07 Olympiad Jane is molistic and slatty. Jennifer is cluvious and brastic. Molly and Kyle are slatty but danty. The teacher is danty and cloovy. Mary is blitty but cloovy. Jeremiah is not only sloshful but also weasy. Even though frumsy, Jim is sloshful. Strungy and struffy, Diane was a pleasure to watch. Even though weasy, John is strungy. Carla is blitty but struffy. The salespeople were cluvious and not slatty. Which of the following are you (most) likely to hear? • Meredith is blitty and brastic. • The singer was not only molistic but also cluvious. • May found a dog that was danty but sloshful. What quality or qualities would you be looking for in a person? • blitty • weasy • sloshful • frumsy Explain!