Basic Phonology of English

advertisement

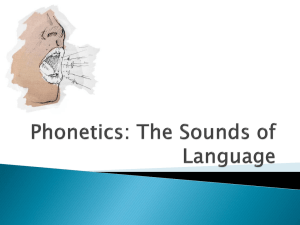

Basic Phonology of English Christine Tanner WGU September 2011 Voiced Sounds • Voiced sounds are made when air is forced past the vocal cords, causing them to vibrate (CelceMurcia, 2001). • This phenomenon happens to the consonants of a language. – There are two easy ways to tell if a word is “voiced” (Celce-Murcia, 2001). • Place your hand on your throat while you speak. If a word or sound makes your hand vibrate, it is voiced. • Place your hands over your ears and listen for the vibration. Voiced Sounds (Edwards, 2003, p. 28) Voiced Sounds This is a chart of Voiced Sounds from http://www.uiowa.edu/~acadtech/phoneti cs/english/frameset.html Voiceless Words • Voiceless sounds are made when air is forced past the vocal cords without the vocal cords vibrating (Celce-Murcia, 2001). – There are two easy ways to tell if a sound is “voiceless” (Celce-Murcia, 2001). • Place your hand on your throat while you speak. If a sound does not make your hand vibrate, it is voiceless. • Place your hands over your ears and listen for the air “whooshing” out of your mouth. Voiceless Sounds (Edwards, 2003, p. 28) Voiceless Sounds This is a chart of Voiceless Sounds from http://www.uiowa.edu/~acadtech/phoneti cs/english/frameset.html Places of Articulation • According to Celce-Murcia (2001, p.42), the articulators are the “more movable part of the articulatory system.” • Celce-Murcia (2001, p.42) also says that the “place of articulation is where the contact with the articulators occurs.” Places of Articulation • Let’s take a look these places of articulation… Places of Articulation (Edwards, 2003, p. 25) Places of Articulation • Oral cavity = mouth • Nasal passageway = nose • Main articulators = lower lip and parts of the tongue • Uvula = the small flap of skin at the back of your mouth • Velum = soft palate (when the hard palate becomes softer) Celce-Murcia (2001) Places of Articulation • Alveolar Ridge = the upper jaw bone • Nasal cavity = above the soft and hard palates; resonating chamber • Mandible = the lower jaw bone • Tongue tip = part of the tongue closest to the teeth • Tongue back = the part of the tongue below the soft palate • Tongue blade = the rest of the tongue; in between the tongue tip and the tongue back Articulatory Anatomy (n.d.) Manner of Articulation • Manner of articulation refers to how the airflow changes when someone tries to make a sound – based upon the obstacles the air makes within the places of articulation (CelceMurcia, 2001). • There are two main groups (Celce-Murcia, 2001): – Obstruents – sonorants Manner of Articulation: Obstruents • Obstruents: – Stops (or plosives) are what the name implies – the air is stopped before it can be released. This causes the air to build behind both lips before it is finally released. • Words that contain stops/plosives: – Bought - /b/ sound – Pad - /p/ sound (Celce-Murcia, 2001) Manner of Articulation: Obstruents • Fricatives are words that build friction in the places of articulation. This friction happens because two of the places used to create this sound approach each other and come close to touching – but do not touch. – Words that contain fricatives: • Thing, fish, violin (Celce-Murcia, 2001) Manner of Articulation: Obstruents • Affricates are a sound combination of a stop plus a fricative. Air pressure builds (like a stop) and then is released through a narrowed passage (like a fricative). – Words that contain fricatives: • Judge, chipper, and chisel (Celce-Murcia, 2001) Manner of Articulation: Sonorants • Approximants are where the airflow moves without much obstruction. – Types of approximants • Liquids • Glides/Semivowels (Celce-Murcia, 2001) Manner of Articulation: Sonorants • The liquids are /l/ and /r/. “[T]he airstream flows along the sides of the tongue” • Glides or semivowels are /y/ and /w/. These act a lot like the liquid sounds but they can be consonants in words with syllable-initial position or the can represent vowel sounds in dipthongs. (Celce-Murcia, 2001) Manner of Articulation (Edwards, 2003, p. 32) Manner of Articulation (Edwards, 2003, p. 30) Features Which Do Not Distinguish Phonemes: Syllabic vs. Nonsyllabic • Syllabic is when a consonant sounds like a vowel. /n/ and /l/ tend to follow this pattern more so than other letters. • Some examples from Celce-Murcia (2001, p. 67) include: – Kitten – Little – tunnel Features Which Do Not Distinguish Phonemes: Syllabic vs. Nonsyllabic • If a syllabic sound has the possibility to sound vowel-like, then nonsyllabic sounds continue to function as consonants. – Examples: • Cat • Chrissi Features Which Do Not Distinguish Phonemes: Stress vs. Nonstress • Stress is where you put the emphasis in a word. The stress helps to clearly state which word/sound is being pronounced. – Read and read are the written the same. In the following sentences, where the stressed letter is changes how the word is pronounced. • I read the book. (nonstressed) • I (will) read the book. (stressed) (Celce-Murcia, 2001) Features Which Do Not Distinguish Phonemes: Aspiration vs. Nonaspiration • Aspirated means that there is a small puff of air that builds up before the sound is released, mainly due to a stop or plosive. “Pa” is aspirated. If you put your hand in front of your mouth when you say “pa,” you can feel a strong puff of air exit the lips. (Celce-Murcia, 2001) Features Which Do Not Distinguish Phonemes: Aspiration vs. Nonaspiration • A sound is nonaspirated when there is no such build up and explosion of air from the mouth. Putting an “s” in front of “pa” to make “spa” smooths out the /p/ sound, softening the puff of air from your mouth. (Celce-Murcia, 2001) Importance of Understanding Characteristics of Speech • Knowing the characteristics of speech will enable ELL teachers to better teach English to their students. • Teachers can help students directly with pronunciation errors – especially the most common pronunciation errors. – This will help students build self-confidence in their abilities to speak. (Lightbrown, 2006) Effects of Understanding Characteristics of Speech on Learning • Students will have more confidence in their abilities and be more willing to take further steps in their language learning. • Students are aware of their errors and can invent ways to work around their errors – with the focus being on communication. – This can help students be more understandable to their peers and others around them –even if they still have a strong accent. References • Articulatory Anatomy. (n.d.) The University of Iowa. Retrieved September 11, 2011 from http://www.uiowa.edu/~acadtech/phonetics/anatomy.htm • Celce-Murcia, M.A. (Ed.). (2001). Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle Publishers. • Edwards, H.T. (2003). Applied phonetics: The sounds of American English (3rd ed.). Thomson Delmar Learning. • Lightbrown, P.M., & Spada, N. (2006). How Languages are Learned (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univserity Press. • Phonetics: The Sounds of American English. (n.d.) The University of Iowa. Retrieved September 11, 2011 from http://www.uiowa.edu/~acadtech/phonetics/english/fram eset.html