Phonetics

advertisement

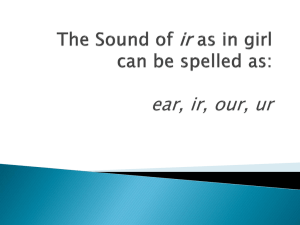

Phonetics: The physical manifestation of language in sound waves. ◦ How sounds are articulated (articulatory phonetics) ◦ How sounds are perceived (auditory phonetics) Phonology: The mental representation of sounds. English orthography (writing system) is not accurate in representing sounds: Did he believe that Caesar could see the people seize the seas? The silly amoeba stole the key to the machine We need a more accurate representation of sounds: IPA (Fromkin, Rodman, Hyams p.223) The smallest units of language. Every language has its own inventory of linguistic sounds. Phonemes can be divided into 2 types: 1. Consonants 2. Vowels Keep in mind: We are not talking about letters here! How are phonemes produced? Consonants are produced by obstructing the flow of air as it passes from the lungs through the vocal tract. When we describe a consonant, one of the features we use is its place of articulation. The other feature is the manner of articulation. Examples of obstructing airflow to produce a consonant: To form the initial [p] sound in “pill”, we put our lips together to shut off the flow of air before releasing it. Sounds that are created by obstructing the flow of air with both lips are called bilabial Compare the [p] sound with the [f] in “fill”. How is it produced? Sounds like [f] are called labiodental Going further back in the mouth: Pronounce the “th” sound as in “thin”. How is it produced? The [θ] sound is called interdental (inter= between, dental= teeth) Consider the [s] sound as in “soup”. How is it produced? By putting the tip of the tongue right behind the upper front teeth. This part of the mouth is called alveolar ridge. Sounds like /s/ are called alveolar. Compare the [s] sound to the [ʃ] sound in “shell”. Where does the tongue move? Sounds produced in this area are called palatal sounds. The soft area further back is called velum. Sounds produced in this area are called velar sounds. Sounds in this area are produced by touching the heel of the tongue on the velum. Examples of these sounds are: [g] and [k] Finally, we arrive at the glottis –the end of the vocal tract and beginning of your throat. There is only one glottal sound: /h/ Place of Articulation Consonant Bilabial [p] [b] [m] Labiodental [f] [v] Interdental [θ] [ð] Alveolar [t] [d] [n] [s] [z] [l] [r] Palatal [ʃ] [ʒ] [tʃ] [dʒ] Velar [k] [g] [ŋ] Glottal [h] Describing the features of Consonants. What distinguishes [p] from [b] or [b] from [m]? All three are bilabial sounds… Speech sounds vary in the way the airstream is affected as it flows from the lungs up and out of the mouth and nose. Voiced and voiceless sounds ◦ When the vocal cords are apart when speaking, air flows freely through the glottis. Sounds produced in this way are voiceless. ◦ If the vocal cords are together, the airstream forces its way through and causes them to vibrate Try it out: put your hand to your throat and produce a [z] sound as in “buzz”. Now do the same with [s] as in “bus”. The distinction is very important in English as it may change the meaning of the word: rope/robe choke/joke fate/fade rack/rag Quick exercise: Of the sounds discussed so far, which are voiced and which are voiceless. Pronounce them with your hand at your throat. [p] [s] [m] [tʃ] [h] [z] [ʃ] [ʒ] [dʒ] [b] [θ] [l] [t] [d] [b] and [p] sounds are distinguished as voiced/voiceless. But how is [b] different from [m]? When the uvular blocks the airway through the nose, the sound is oral. When the uvular is not raised, air escapes through the nose and the mouth. This is called a nasal sound. If [m] is a nasal, what other nasals can you identify? [m] ew [n] [ŋ] To produce the [t] sound, you place the tongue on the alveolar ridge and obstruct the flow of air. The [s] sound is produced at the same place of articulation. What is different about them? Test for yourself: produce the sounds and observe what is happening to the airflow. When the airflow is completely stopped, the sound is a stop. When the airflow is only partially stopped, it’s a fricative. Quick exercise: Of the sounds discussed so far, which are stops and which are fricatives? Pronounce each and decide. [p] [s] [θ] [t] [d] [z] [ʃ] [ʒ] [k] Affricates are produced by a stop which is followed immediately by gradual release of air. Stop + fricative = affricate ◦ There are only two: [tʃ] and [dʒ] Liquids ◦ During the production of the sounds [l] and [r], there is no real obstruction of the airflow that causes friction. Hence, these sounds are not stops, fricatives or affricates. They are called liquids Glides ◦ Are not causing significant obstruction and are always followed by vowels. ◦ [j] and [w] Consonants [p] pit [b] bite [m] man [t] tool [d] dance [n] nice [k] cat [g] girl [ŋ]singer [f] foul [v]vote [s] side [z] buzz [θ] thigh [ð] father [ʃ] shoe [dʒ] judge [l] loud [r] rooster [j] yes [ʒ] measure [tʃ] choke [w] witch [h] hat Vowel Qualities The placement of the body of the tongue: ◦ Vertical: high – mid – low ◦ Horizontal: front – central – back The shape of the lips: ◦ Rounded – Unrounded The degree of the vocal tract contraction: ◦ Tense – Lax Experiment: Say the words “meet” and “mat”. What happens to your jaw? Now say the word “mate” in between. High [i] meet Mid [e] mate Low [æ] mat Frontness is determining where the tongue is positioned horizontally. Say the words hack [hæk] and hah in sequence: “hack, hah, hack, hah, hack, hah. You should be able to observe the tongue movement. front vowels: [i] [ɪ] [e] [ɛ] [æ] Central vowels: [ə] [ʌ] back vowels: [u] [o] [ɔ] [a] [ʊ] Vowels differ in roundness of the lips. a In English, there are tense and lax vowels Compare “beat” and “bit”. Both sounds are high, front vowels, but they differ in tenseness of muscles in the vocal tract. Tense Lax [i] beat [ɪ] bit [e] bait [ɛ] bet [u]boot [ʊ] put [o]boat [ɔ] bore The previously discussed vowels are also called monophthongs Diphthongs are a combination of 2 vowel sounds. In English, there are 3 (main) diphthongs. Consider following words: kite bout boy [aj] [aw] [ɔj] Consonants [p] pit [b] bite [m] man [t] tool [d] dance [n] nice [k] cat [g] girl [ŋ]singer [f] foul [v]vote [s] side [z] buzz [θ] thigh [ð] father [ʃ] shoe [dʒ] judge [l] loud [r] rooster [j] yes [ʒ] measure [tʃ] choke [w] witch [h] hat Diphthongs Vowels [i] beat [ɪ] hit [e] gate [aj] kite [ɛ] bed [æ] pan [u] boot [aw] bout [ʊ] put [ʌ] cut [o] go [ɔj] boy [ɔ] talk [a] father [ə] alone Quick exercise: Answer following questions in IPA 1. /wær du dɒktərs wərk?/ 2. /wʌt kʌlər ɪz ðə skai?/ 3. /wʌt ɪz θri taɪmz θri?/ 1. 2. 3. /hɔspɪtəl/ or /haspətəl/ /blu/ /najn/ The mental representation of sounds Phonology is concerned with the sound structure/patterns of languages. What syntax is for grammar, phonology is for phonetics. Knowledge of phonology determines how we pronounce morphemes depending on their context. Just as morphology has rules, phonology has its own rules. Most English nouns have a plural form: cat/cats, dog/dogs, fox/foxes You might think an “-s” makes nouns plural, but when you listen carefully, you’ll here a different pronunciation of that “-s”. A B C D cab cap bus child cad cat bush ox bag back buzz love cuff garage mouse criterion The final sound of the plurals in A is a [z] a voiced alveolar fricative. For column B, the plural ending is an [s] – a voiceless alveolar fricative. Column C is [əz] Column D are irregular endings. Do you think the variance of plural pronunciation is random? There’s a phonological rule behind it. To understand it, we must analyze the surrounding sounds. To understand the surrounding sounds, we need to look at minimal pairs. Minimal pairs are words that only differ in one sound segment. For example ship/sheep cat/mat Minimal pairs from the previous examples are cap/cab bag/back bag/badge These minimal pairs differ in the final sound segment, so the final sound must determine the pronunciation of the plural ending. Allomorph Environment [z] After [b], [d], [g], [v], [ð], [m], [n], [ŋ], [l], [r], [a], [ɔj] [s] After [p], [t], [k], [f], [θ] [əz] After [s], [ʃ], [z], [ʒt], [ʃ], [dʒ] Allomorph Environment [z] After voiced nonsibilant segments [s] After voiceless nonsibilant segments [əz] After sibilant segments