Mistaken or Ambiguous Language in Wills

advertisement

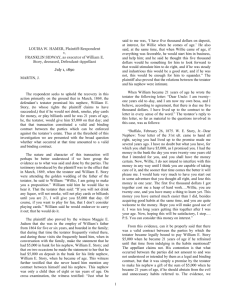

Construction of wills If a primary goal of trusts and estates law is to carry out donor intent, we need principles for situations in which donor intent is not obvious Mistaken or ambiguous language (today’s class) Death of beneficiary before death of testator Changes in property after execution of a will 1 Construction of wills Mistaken or ambiguous language Ordinarily, testators are bound by the words in their wills But what if a mistake was made? Traditionally, courts have not looked beyond the language of the will except to resolve obvious ambiguities—if the will could be executed as written, then it was so executed More and more states are allowing more and more extrinsic evidence to carry out the testator’s intent 2 Fulfilling the decedent’s intent “The controlling consideration in determining the meaning of a donative document is the donor’s intention. The donor’s intention is given effect to the maximum extent allowed by law.” Restatement § 10.1 (page 335) But traditional rules require adherence to the plain meaning of the will, with no reformation of the will. Extrinsic evidence allowed to resolve some ambiguities in text but not to prove that the testator intended something other than what was written 3 For an illustration of the traditional view, we have Mahoney v. Grainger, p.336 What were the facts? Helen Sullivan instructed her attorney to divide the residue of her estate equally among her 25 or so first cousins The lawyer wrote the will to divide her residue to her living “heirs at law,” in equal shares It turned out that she had a maternal aunt, who was her sole living heir 4 Mahoney v. Grainger, Mahoney v. Grainger p.336 Aunts & Uncles Father Mother Frances Greene Aunts & Uncles ?? First Cousins ?? Helen ?? First Cousins What result under the UPC? Half to Frances and the first cousins on Helen’s mother’s side; half to the first cousins on Helen’s father’s side 5 Table of Consanguinity p. 93 6 Mahoney v. Grainger Was there any ambiguity in the language of the will? What language might have been viewed as creating an ambiguity? Not according to the court. It may not have reflected Ms. Sullivan’s intent, but its application was clear The part about dividing the residue among “heirs at law,” “share and share alike” suggests she expected more than one person to take the residue Why might she have used that language even though her aunt was her sole heir? In case her aunt predeceased her 7 Exclusion of extrinsic evidence, note 2, p.338 Did the court get it right (in terms of testator intent) by giving Smith’s bequest to the Nevada corporation? On one hand, we may conclude that the testator cared more about the local nursing home than an out-of-state corporation On the other hand, we may conclude that the testator cared more about the company that owned the home when she wrote the will than about the company that purchased the home after she wrote the will 8 Resolving ambiguities Traditional courts do not allow extrinsic evidence to resolve patent ambiguities (those apparent from the text itself) Where devise is unclear, it could pass through a residuary clause or through rules of intestacy; sometimes later provisions trump earlier provisions, sometimes specific provisions trump general provisions Traditional courts allow extrinsic evidence to resolve latent ambiguities (which niece named Alicia?) Indiana allows extrinsic evidence for both patent and latent ambiguities 9 The causes and effects of will defects Cause: Intentional Wrongdoing Cause: Innocent Acts Effect: Effect: Lack of Volition Mistaken Terms Undue Influence, Duress Fraud (relief granted) Lack of Capacity, Insane Delusion (relief granted) (relief granted) Mistake (no relief) And courts fix mistaken revocation of wills under DRR or compensate for the testator’s failure to update a will after a divorce or the birth of a child 10 Arnheiter v. Arnheiter (p.343) Arnheiter v. Arnheiter and the trend in favor of reformation of wills Reformation – NOT allowed: I direct my Executor to sell my undivided onehalf interest of premises known as No. 304 Harrison Avenue . . . . No. 317 What happens to 317 Harrison? It falls into the residue. Falsa demonstratio non nocet (mere erroneous description does not vitiate) – allowed: I direct my Executor to sell my undivided onehalf interest of premises known as No. 304 Harrison Avenue . . . . 11 Estate of Gibbs Estate of Gibbs p. 344 Reformation – NOT allowed: W. Robert J. Krause, now of 4708 North 46th Street, Milwaukee, Wisconsin… Ignoring certain details – allowed: Robert J. Krause, now of 4708 North 46th Street, Milwaukee, Wisconsin… 12 Erickson v. Erickson, p. 345 Erickson v. Erickson Open reformation of a will Sept. 1, 1988 Dorothy and Ronald marry. Feb. 22, 1996 Sept. 3, 1988 Ronald and Dorothy execute mutual wills, naming each other as executor and beneficiary, with their children, collectively, as contingent beneficiaries. Ronald Ronald dies. Dorothy Revoked by marriage?? Laura Ellen Alicia Thomas Chris Maureen Kathleen If will is revoked, D takes half the estate, with R’s children taking the other half 13 Erickson v. Erickson Note that both the trial court and the supreme court wanted to probate the will (which by statute was revoked by marriage), but for different reasons According to the trial court, it was clear from the will itself that Ronald intended it to survive the wedding (he left his estate to his fiancée, he named her his executrix and guardian of his daughters upon his death) According to the supreme court, the language of the will itself did not provide for the contingency of a subsequent marriage. Nevertheless, extrinsic evidence could be admitted to establish the testator’s intent 14 Erickson v. Erickson Why admit extrinsic evidence to correct a lawyer’s error? There is no meaningful difference between admitting evidence of a mistake and admitting evidence of fraud, duress or undue influence While the signing of the will creates a presumption that it accurately reflects the testator’s intent, the presumption should be rebuttable A clear and convincing evidence standard for overcoming the presumption will ensure that the exception for admitting extrinsic evidence is a narrow one 15 Correcting mistakes in wills Mahoney v. Grainger No extrinsic evidence; No reformation. Arnheiter v. Arnheiter; Estate of Gibbs The court “has no power to reform” but court reforms anyway. Erickson v. Erickson; UPC §2-805 Open reformation; extrinsic evidence permitted. 16 UPC §2-805 (2008), p. 351: Reformation to Correct Mistakes “The court may reform the terms of a governing instrument, even if unambiguous, to conform the terms to the transferor’s intention if it is proved by clear and convincing evidence that the transferor’s intent and the terms of the governing instrument were affected by a mistake of fact or law, whether in expression or inducement.” 17 Substantial Compliance and Harmless Error Substantial Compliance Types of The court may deem a Curative defectively executed Doctrines will as being in accord with statutory formalities if there is clear and convincing evidence that the purposes of those formalities were served. Harmless Error Rule (UPC §2-503) The court may excuse noncompliance if there is clear and convincing evidence that the decedent intended the document to be his will. 18 UPC §2-503: Harmless Error Although a document or writing added upon a document was not executed in compliance with Section 2-502, the document or writing is treated as if it had been executed in compliance with that section if the proponent of the document or writing establishes by clear and convincing evidence that the decedent intended the document or writing to constitute (i) the decedent’s will, (ii) a partial or complete revocation of the will, (iii) an addition to or an alteration of the will, or (iv) a partial or complete revival of his [or her] formerly revoked will or of a formerly revoked portion of the will. 19 UPC §2-502(b)-(c). pp. 227, 279 (b) [Holographic Wills.] A will that does not comply with subsection (a) is valid as a holographic will, whether or not witnessed, if the signature and material portions of the document are in the testator’s handwriting. (c) [Extrinsic Evidence.] Intent that a document constitute the testator’s will can be established by extrinsic evidence, including, for holographic wills, portions of the document that are not in the testator’s handwriting. 20