Sentence_Fragments1

advertisement

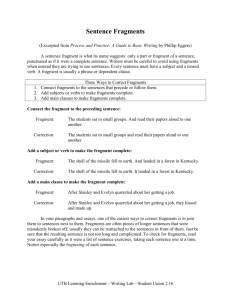

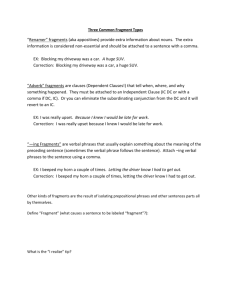

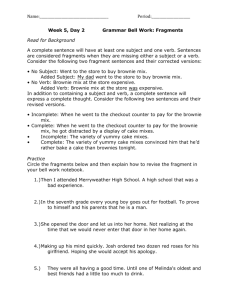

Complete sentences have at least a subject and a verb. The subject is the actor of the sentence and the verb is what the subject does. Example: My cat eats. “My cat” is the subject. The verb is “eats.” Sometimes, though, a subject and a verb are not enough to make a complete sentence. The following slides show some tricky sentence fragments and how to spot them. A sentence must also be a complete thought. Complete sentence: Although it is windy, I will still go for my walk today. Fragment: Although it is windy. In the fragment “it” is a subject and “is” is a verb, but the word “although” leaves the reader expecting more to the sentence and the thought. For this reason, “Although it is windy” is what is called a dependent clause, that is, it depends on “I will still go for my walk today” to make sense as a thought. Look out for subordinating conjunctions (conjunctions that make one part of the sentence dependent on another part). If you spot one at the beginning of one of your sentences, make sure you have completed the thought. Some common subordinating conjunctions: although, even though, because, when, while Also, look for sentences that begin with prepositions. Make sure you have completed the thought. Complete thought: You will find some letters on the table./On the table, you will find some letters. Fragment: On the table. Some common prepositions: on, onto, in, into, out, under, over, from, around, about, to, toward, by, for, until, unless, after A sentence that begins with “and,” “but,” or “or” has traditionally been considered to always be a sentence fragment. This rule is changing. Many people now accept such sentences as long as the rest of the sentence is a complete thought. Be careful, though, before you start a sentence with one of those words. Many professors still hold with the old rule. To play it safe, avoid these words at the beginning of a sentence. These words also often appear at the beginning of sentence fragments. Notice the difference between complete sentences/complete thoughts and sentence fragments. Complete sentence: He drove the truck that he bought from me last year. Fragment: That he bought from me last year. Complete sentence: We went with Susan, who loves roller coasters. Fragment: Who loves roller coasters. Exception: “Who loves roller coasters?” is acceptable as a question. After it rained, Jim went to the store. The one on the corner. He bought flour and milk. And he got some eggs. Even though it was raining, Jim walked home with his groceries. Because his car was in the shop. When he got home, he mixed up eggs, butter, and sugar in a bowl. He seemed to have lost the flour. Where could it be? On the table. Jim added some vanilla and the flour. Then, he dropped globs of dough on a sheet and placed it in the oven. Cookies. He could hardly wait. After it rained, Jim went to the store. The one on the corner. He bought flour and milk. And he got some eggs. Even though it was raining, Jim walked home with his groceries. Because his car was in the shop. When he got home, he mixed up eggs, butter, and sugar in a bowl. He seemed to have lost the flour. Where could it be? On the table. Jim added some vanilla and the flour. Then, he dropped globs of dough on a sheet and placed it in the oven. Cookies. He could hardly wait. Sentence fragments aren’t always bad. They can be used in informal writing as long as meaning is clear. People tend to speak using fragments frequently. Sentence fragments also often appear in creative writing. You will probably see them in your favorite novels. For academic work, however, only use complete sentences. Now that you know what fragments are and how to spot them, you can use them with care.