Autonomous to serve

advertisement

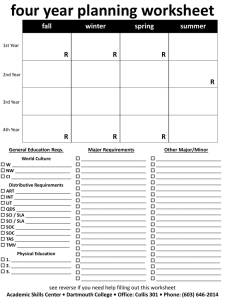

Autonomous to serve Governing bodies, autonomy, and responsiveness of US universities Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org 2 Overview • historical background of US colleges’ autonomy • autonomy of public and private higher education institutions (HEIs) • basics of the structure of US HEIs • governing bodies and external governance • governing bodies in relation to other university authorities • governing bodies and adaptability of US HEIs Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 3 Autonomy—the very beginnings • College, later named after John Harvard, was established in 1636 • at first it was fully under the authority of the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony • 1642—the creation of the board of overseers: – governor, deputy governor, president of the school, six clergymen from Cambridge, Watertown, Charlestown, Boston, Roxbury, and Dorchester • 1650—Harvard Corporation: school’s independency Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 4 Autonomy—colonial times • Harvard Corporation consisted of 7 members (including president and treasures) • self-perpetuating body • the decisions were to be confirmed by board of overseers • sometimes such situation made decision-process difficult • after 1782 the situation changed and Harvard gained full autonomy • the pattern of Harvard College was followed by other colonial colleges, including king’s colleges Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 5 Independency and autonomy • Just after the American Revolution there were two philosophies of state/governmentHEI relationship: – closer dependency and use of HEIs as means of public policy (e.g.: „the enduring dream” of federal national university) – greater autonomy and independency of colleges and universities (strongly supported by private schools) • the result of the clash: Dartmouth v. Woodward case in 1819 Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 6 Dartmouth case • 1815 because of the conflicts between the president—John Wheelock—and the board of trustees, Wheelock was dismissed • later—the General Court of New Hampshire tried to change the college charter • Wheelock sued New Hampshire to the Supreme Court • John Marshal (the Chief Justice) explained that no external force can change the nature of the college • “there shall be in the said Dartmouth College, from henceforth and forever, a body politic consisting of trustees of said Dartmouth College.” Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 7 Public universities autonomy • Moore v. Board of Regents of University of the State of New York in 1977 secured the autonomy of the institutions of higher education • it ruled that only the board of trustees has right to amend programs of studies, not state agency, controlling higher education • In Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 1957, Justice Felix Frankfurter defined the autonomy of HEI as the right: – “to determine for itself on academic grounds who may teach, what may be taught, how it shall be taught, and who may be admitted to study.” Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 8 Dartmouth Case • Decision of the Supreme Court secured the autonomy of private institutions • they are ruled by the most important regulation: their own charter, therefore they do not have to grant some constitutional rights, including freedom of speech • Dartmouth case does not influence state-public institution relations directly • public institutions are (at least theoretically): – state founded – state funded – state controlled Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 9 Typical structure of US HEI • at the very top: – governing body (called: board of trustees, board of overseers, board of governors) • the board: – hires and fires the president – shapes the mission of the institution – supervises crucial financial decisions • the president is the executive officer of the school, reports directly and only to the board Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 10 Typical structure of US HEI • president is responsible for the administration of the school: – hires and fires (usually at his/her discretion) officers – implements school’s mission in everyday activity – is responsible for school’s cooperation with external bodies (including government and business) • academic elective bodies (e.g. senate): – they are loosing their importance – tend to be advisory bodies (president enjoys the only real executive power) Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 11 Governing board • as the self-perpetuating body, the board is responsible for its composition itself • public schools have to obey state regulations (eg. a person or a number of persons appointed by governor) • especially among public schools: some members are appointed by senates • once established board remains independent: „arm’s length” rule protects from too strong political influence Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 12 Governing board • this is not the representation of the faculty members (i.e. senate) • its consists of elected or appointed members • usually the majority are the alumni of the school • they do not to be academics, rather successful entrepreneurs • they know the demands of the labor market since many of them are employers themselves Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 13 Governing board • serves as the buffer and mediator between the school and external forces (including government) • it is the guardian of the autonomy • even in public schools the government (federal, state, and local) cannot force them to change programs of studies or close less popular ones • such decisions must be approved by the board Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 14 Autonomy and responsiveness • the challenges of the 1980s forced US HEIs to be more market-oriented and open to the demands of students and labor market • responsiveness meant response to those demands • president in collaboration with the board can easily and quickly change the offer of the school • they do not need to wait until government adopt new policies Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn? 15 Autonomous to serve • many scholars and administrators call for more responsive university • autonomy does not mean seclusion • autonomy means openness to new challenges • schools not dependent to government and politicians can respond: – quicker – more reasonable – cheaper Dr. Radoslaw Rybkowski: Autonomous to serve radoslaw.rybkowski@fulbrightmail.org Drivers of Change: What Can We Learn?