The Legal system

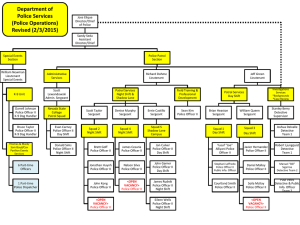

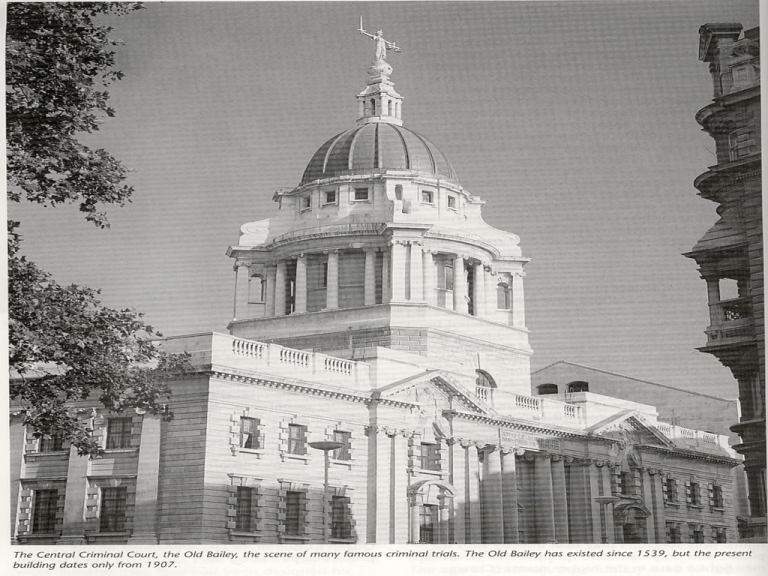

advertisement

LAW ENFORCEMENT The Legal system The law is one of the most traditional areas of national life and the legal profession has jealously protected its position against outside attack. - Its main virtue is its independence from the system of government and as such, a safeguard of civil liberties. - its main vice lies in its resistance to reform, and the maintenance of its own privileges which may be contrary to public interest. 1. England and Wales the legal system for England and Wales does not have a criminal or civil code, but is founded upon two basic elements: - Acts of Parliament or statute law - Common law (which is the outcome of past decisions and practices based upon custom and reason) Common law has slowly built up since Anglo-Saxon times 1000 years ago, while Parliament has been enacting statutes since the 13th century All criminal law is set out in Acts of Parliament, while the greater part of civil law depends upon common law. European Community law also applies to Britain by virtue of its membership of the European Union and it takes precedence over domestic law. In 1997, Britain finally took steps to incorporate the European Convention on Human Rights into domestic law TYPES OF COURT CIVIL House of Lords Court of Appeal (Civil Division) CRIMINAL House of Lords Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) High Court Chancery Family Queen’s Bench Country Court Crown Court Magistrates’ Court (Juvenile Court) Composition of Judiciary category men women Ethnic minorities Law Lords 12 0 0 Appeal Court judges 31 1 0 High Court judges 97 7 0 Circuit judges 512 30 5 2. Scotland The Scottish legal system is similar to the English one, but is more influenced by Roman law, like other systems in Europe. Its main courts are - the Sheriff’s Courts (like Crown Courts) for civil and criminal cases, - The Court of Session for civil cases. - The Court of Session is divided into: Outer House (a court of first instance) Inner House (a court of Appeal), has 2 divisions of 4 judges respectively, * 1 under the direction of the Lord President, * 3 under the direction of the Lord Justice Clerk Less serious cases are tried in the Sheriff’s Courts (like Crown Courts) and District Courts More serious cases go to the High Court of Justiciary. Juries are made up of 15 rather than 12 citizens. Minor offences are dealt with in District Courts (the equivalent of Magistrates’ Courts). The senior law officer in the High Court of Justiciary and in all Scotland is the Lord Justice General, and the second rank is the Lord Justice Clerk. The Crime and the Police 1. The crime The initial decision to bring a criminal charge normally lies with the police, but since 1986 a Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has examined the evidence on which the police have charged a suspect to decide whether the case should go to Court. A Court normally consists of 3 lay magistrates who are advised on points of law by a legally qualified clerk. A Crown Court is presided over by a judge, but a verdict is reached by a jury of 12 citizens, randomly selected from the local electoral rolls. The judge must make sure that the trial is properly conducted, that the ‘counsels’ (barristers) for the prosecution and defence comply with the rules regarding the evidence that they produce and the examination of witnesses, and that the jury are helped to reach their decision by the judge’s summary of the evidence in a way which indicates the relevant points of law and the critical issues on which they must decide in order to reach a verdict. Like Parliament, Crown Courts are adversarial, contests between 2 opposing parties. Neither the prosecution nor defence counsel is concerned to establish the whole truth about the accused person. Both may well wish to avoid aspects which weaken their case that the accused person is either guilty beyond reasonable doubt or that sufficient reasonable doubt exists for that person to declare ‘not guilty’. A person convicted in a magistrates’ court may appeal against its decision to the Crown Court. An appeal against a decision to the Crown Court may be taken to the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division), but it is seldom successful. The Court of Appeal dislikes overturning a Crown Court decision unless the evidence is overwhelming or there has been some error of legal procedure. The highest court in the land is the House of Lords, which will consider a case referred from the Court of Appeal where a point of general public importance seems to be at stake. In practice the Lords are represented by five or more of the nine Law Lords. 2. The Police The British police force was a source of great pride (20 years ago). “What’s gone wrong with the Police?” (in early 1990). It referred to the frequency of scandals during the 1980s involving the police, concerning the excessive use of violence to maintain public order (Brixton riots 1981, the miners’ strike 1984-85, the Wapping strike 1986, the anti-poll tax riots 1990); violence in the questioning of suspects (particularly, but not exclusively, in connection with Northern Ireland); etc. Unlike the Police in almost every other countries, the British police officers enjoyed a trusted, respected, and friendly relationship with the public. The ‘bobbies on the beat’ made it their business to learn about their neighbourhood. This was probably a rosy, idealized view of the police, but it was a genuine source of pride that almost alone in the police world, the British bobby was unarmed. As Ralf Dahrendorf says, “It is hard to exaggerate the significance of the fact that the British police did not, and very largely do not, carry weapons.” The British police are probably still among the finest in the world, but clearly there are serious and growing problems. At the end of 1980s reported that one in 5 people believed the Police used unnecessary force on arrest, falsified statements, planted evidence and used violence in police stations. Until 1987 the police investigated alleged police malpractice themselves. And many people believed that police malfeasance is more widespread than the statistics would suggest. As the challenges of modern society became more complex, the response of the Conservative government was to give the police more manpower and more money. However, there is no indication these extra resources had any effect at all on recorded offences which rose in England and Wales. * in other words, the steepest increase in crime coincided with the greatest increase in crime prevention expenditure. LEGAL PROFESSION Traditionally the legal profession has been divided into two distinct practices, each with entrenched rights: - only solicitors may deal directly with the public, and - only barristers (professional advocates) may fight a case in the higher courts (Crown Courts and the High Court). Both have maintained their own selfregulating bodies, the Law Society for solicitors and the Bar for barristers. A member of the public dissatisfied with the services of a solicitor may complain to the Law Society, but this does not often take action against its own members except in the case of some gross offence or negligence. The Law Society has often infuriated members of the public by advising them to take their complaint to another solicitor. Theoretically, the barristers are the senior branch of legal profession. They are able to reach the top of the profession, a High Court judgeship. To become a barrister, a candidate must obtain entrance to one of the 4 Inns of Court, law colleges which date from the middle ages, complete the legal training and pass the Bar examination. A newly qualified barrister will enter the ‘chamber’ of an established one, and slowly build up experience and a reputation as an effective advocate in the higher courts. Exercises 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Discuss about the court system in England and Wales is organized. Discuss about the role of the police in law enforcement. How does the British way of treating offenders differ from treatment in our country? Do you think that a relatively small legal profession, as in Britain, is desirable? Discuss! What are the two basic sources of English Law? Explain.