MuseumasObject

advertisement

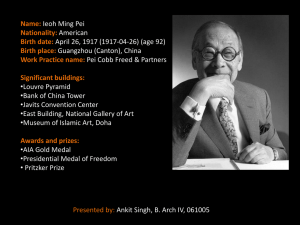

The Museum as Object The Guggenheim Museum, by Frank Lloyd Wright, is one of the first examples of a museum designed by a “signature” architect. The term “signature architect” was not used until the 1970s, but its meaning can be traced back to this kind of commission. The term “signature architect” refers to the culture of celebrated designers whose name is as important an attribute of the commission as is their design talent. Prior to this, the notion of designing a museum or a gallery was viewed as an opportunity for a museum institution and a designer to enhance a collection of art by providing it with the best possible environment for viewing and for curatorial purposes. The idea of “signature design” suggests that the museum patrons come to view the architecture of the building as much as they come to view the collection of paintings, sculptures or other arts housed in the building. While “signature design” is by no means limited to museums and galleries--it is used by corporations and many other institutions--it has a special meaning in the category of museums and galleries. The architecture ultimately becomes part of the collection it houses. The Des Moines Art Center, by Eliel Saarinen, 1948, is an early example of a museum designed by a signature designer. Begun only five years after Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Des Moines Art Center was a more modest design and was finished ten years before the Guggenheim. Native field stone, limestone, and aluminum are the principal materials. Warm wood finishes on the walls are set off by white plaster ceilings with recessed lighting in the coves. The Des Moines Art Center grew rapidly and by the late 1950s needed to expand its gallery space. The museum board turned to the young Chinese-American architect Ieoh Ming Pei to design an addition to the Saarinen building. Pei’s addition was built in the early 1960s and represents the kind of stark geometries and heavy weight used in brutalist and high modern buildings. The addition was sited in such a way that it connected with a courtyard of the Saarinen building but was mostly out of view to the southwest. It took advantage of the sloping site and opened out to a lawn that was eventually planted with a rose garden. Pei’s interior was as stark as Saarinen’s was warm, exposing the reinforced concrete walls directly as the exhibition environment. Some twenty years later, the Des Moines Art Center needed to add additional gallery space as well as other amenties, including a small restaurant/coffee shop and curatorial space. Having used two prominent designers for the museum already, in the early 1980s the board turned to Richard Meier, then at his apex, and commissioned him to design an addition to the Saarinen-Pei complex. Meier surprised the architectural public by using not only his by then characteristic white baked enamel paneling but by adding gray stone to the palette. The effect of the design on both exterior and interior is the creation of a space modulator, interesting in and of itself as well as serving the purposes of the needed gallery and other spaces. The addition was completed in 1985. It is in the courtyard that the three periods of the building stand in dialogue with one another. Meier’s task was to bring some sort of harmony out of the relationship. He did this by mediating between the geometric and abstract qualities of the Pei building and the more human scaled and intimate quality of the Saarinen building with its carefully wrought details in stone and metal. The Meier addition effectively brings a sense of a larger whole to the composition, in part because it is carefully designed neither to overwhelm the earlier parts of the Art Center nor to recede needlessly from them. What is true on the exterior is also true on the interior. The abstract language of modernism is tempered by a human scale and luminosity in the galleries and circulation spaces. Addition to the Landesmuseum, Stuttgart, by James Stirling with Michael Wilford, 1977-83 Site plan Plan of addition The challenge of the design of the Stuttgart Landesmuseum was the need to add a long wing to an existing late 19th-century building in an academic classical style. Stirling and Wilford chose to use classical materials and forms-travertine marble and a rotunda but to contrast them with contemporary materials and forms: steel painted in bright colors and open tubular as well as channel beam structures. These elements are arranged in playful geometries against the more classical elements just as the addition is set against the original museum building in a contrastive arrangement along a major thoroughfare at the edge of the downtown and on the side of one of Stuttgart’s hills. The Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University is another example of a “signature designer” gallery. Peter Eisenman was selected as the architect of the Wexner Center in part by virtue of his position as a cutting-edge designer. He had never designed a gallery or museum before, so we can only attribute the choice of his design by the building committee to their interest in his design as art as well as an embodiment of their program. The Tate Modern represents another category of design: the adaptive re-use of an historic building for the purposes of creating new gallery space. Completed in 2000, the Tate Modern is the conversion of a former power plant (vintage 1920s) into a dramatic gallery for contemporary art as a branch of the Tate Gallery in London. A team of designers from Switzerland undertook the adaptive reuse project. It is thus not a “signature design” in the terms of the other works we have examined. The Richard and Lois Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, by Zaha Hadid, opened in the spring of 2003. It is the first museum in the United States designed by a woman and the first building built in the United States by Zaha Hadid. Hadid’s CAC seems to reject both the classicizing and the modernist buildings adjacent to it. Its verticality also balances the sprawling horizontality of the Aronoff Center across the street.