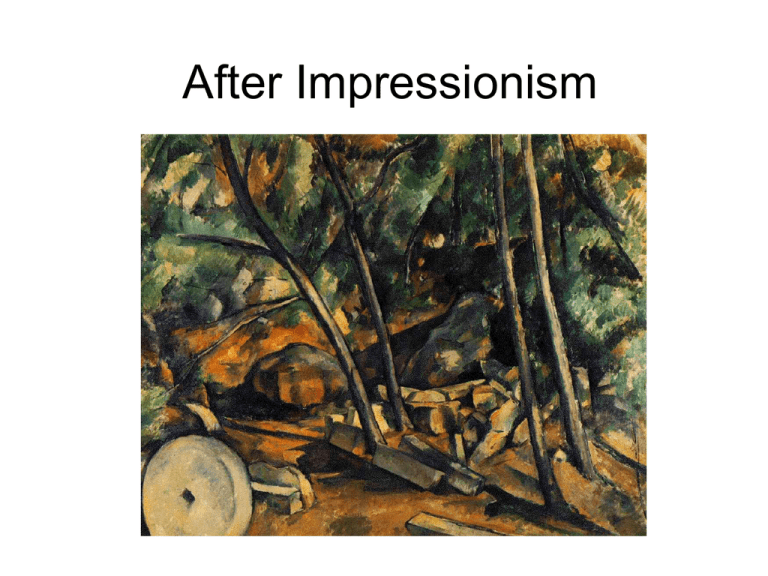

After Impressionism (Gauguin)

advertisement

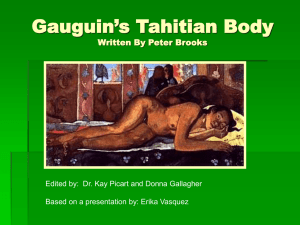

After Impressionism • While it was ridiculed by the Salon and dismissed by the art establishment, Impressionism was to have a profound effect on the work of young European avant-garde artists, many of whom experimented with Impressionist technique in the 1870s and 1880s. Impressionism’s focus on the fleeting moment, objective realism, colour and light, and its preoccupation with modern life excited these painters. • However, by the mid-1880s some artists on the fringe of the Impressionist movement were becoming dissatisfied by the limitations of Impressionist painting. Impressionism’s concentration on the fleeting and the casual resulted in work that was seen to be trivial; without meaning or content. The tendency of Impressionist paintings to focus on the leisure pursuits of the bourgeoisie (wealthy middle classes) sat uneasily with the Socialist ideologies of many young painters. The hurried application of paint in an attempt to capture light through colour, often led to paintings which appeared sketchy or formless. • These limitations proved too restrictive for a number of artists who sought new means of representing their ideas in paint. These artists are often called the Post-Impressionists, although this was not a term that any of them identified with. Some of theses artists had exhibited with the Impressionists and described themselves as Neo- Impressionists or “The New Impressionists” • Some are quite accurately considered Symbolists, due to the way they used colours and imagery to describe ideas and feelings rather than merely representing what was visible. • Divisionism (later to be called Pointillism) was adopted by a number of NeoImpressionists, most notably Georges Seurat. This technique was influenced both by an Impressionist approach to colour, and the theories of contemporary scientists on how the eye processed colour. • In Pointillist paintings the canvas is saturated with tiny dots of pure colour which are then “mixed” in the eye of the viewer. This was an incredibly slow and painstaking This painting lacks approach and Seurat’s largest and most much of the impressive paintings such as Sunday spontaneity and Afternoon on the Island of the Grande freedom of Jatte (1884-6) were carefully composed Impressionist painting, using a large number of preliminary studies. but has a sense of composition, Classicism and monumentality that is missing in Impressionist paintings. Unlike Impressionist paintings, this work is rich in content, and addresses social issues such as class inequality. • Other PostImpressionist approaches include Cloisonnism (where images were reduced to flat planes of, often bright, colour surrounded by dark lines); Emile Bernard, Breton Harvesters • and Intimism (where everyday scenes were painted using, often patterned areas of muted colour). Eduard Vuillard, Sleep, 1891 • Both of these approaches owe much to the popularity of Japanese prints in Europe in the second half of the 19th century. • In Japanese prints images lacked many of the conventions of European painting. The large areas of flat colour, the emphasis on line and the lack of naturalistic perspective forced many PostImpressionist painters to reconsider the possibilities of oil painting. Some artists also developed an interest in non-European Art and folk Art which was to influence their work. • While Impressionist Art can be seen as a break from the art that preceded it, many PostImpressionist artists were more prepared to allow great European Art of the past to influence their painting. • There are Artists working in the Post-Impressionist period who stand alone from any school or group. The most famous of these is the Dutchman, Vincent Van Gogh who from 1880 (aged 27) to his suicide a decade later devoted his life to Art with a religious zeal, creating over 800 paintings. The Sewer, 1888 • Van Gogh’s mature work is typified by rich surfaces of thickly applied paint, with the patterns of the brushstroke clearly emphasised and a use of bold often unnaturalistic colours. His paintings are charged with energy and an emotional intensity that creates a stark contrast with the work of the Impressionists. Starry Night, 1889 • The Impressionists’ Positivist approach led to painting which aimed to directly capture in paint whatever the eye could see. In contrast, Paul Cézanne wrote “The eye is not enough, reflection is needed”. For Cézanne, painting required meaning. Boy with Skull, 1898 • Cézanne is famously quoted as wanting to “re-do Poussin again from nature”. In his landscapes, Cézanne wanted to achieve the sense of order and composition present in the classical landscapes of old Masters such as Poussin but combine it with the energy, colour and observational rigour of Impressionism • The monumentality of Cézanne’s greatest landscapes is achieved through an emphasis on form. In a letter to the painter and critic Emile Bernard, Cézanne advised to “treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone”. Every form, from the foliage of a pine tree to the famous rock of Mont-Saint-Victoire, is treated with an underlying weight and structure. Cezanne’s use of very deliberately placed, strong, directional brushstrokes, underlines the sense of structure and timelessness his landscapes. •Cézanne’s interest in combining an almost sculptural modelling of forms with creating a sense of harmonious balance in the overall canvas is perhaps most visible in his many still-life paintings • By simultaneously representing different viewpoints, distorting perspective, flattening images, and prioritising the overall design of the picture surface, Cézanne redefined the rules of oil painting. Paul Gauguin • French Artist, born Paris, 1848 into a wealthy family • Spent early childhood in Peru with mother’s family • While working as a Stockbroker, Gauguin’s interest in Art developed into a passion which was to see him leave his job and his family. Inspired by the Impressionists, most influentially Camille Pissaro, Gauguin’s paintings of the late 70s and early 80s are very much Impressionist in style. He regularly exhibited his work with the Impressionists between 1877 and 1886. • In 1886, Gauguin first started working in Brittany and the style of his painting started to change. “Four Breton Women Dancing” shows an increased flattening of forms and a lack of spatial depth that shows the influence of Japanese prints. The choice of peasant women as subject matter also makes a stark contrast with the wealthy boating parties of Monet and Renoir. • Gauguin described his new style as Synthetism, by which he meant a style of art in which the form (colour planes and lines) is synthesized with the major idea or feeling of the subject. Breaking away from the Impressionist preoccupation with the study of light effects in nature, Gauguin sought to develop a new decorative style in art based on areas of pure colour (e.g., without shaded areas or modeling), a few strong lines, and an almost two-dimensional arrangement of parts. Yellow Christ 1889 • In Vision After the Sermon (1888) Gauguin attempts to combine in one setting two levels of reality, the everyday world and the dream world. The lower figures are reduced to areas of flat patterns, without modeling or perspective. •The large colour areas are intense and without shadows. The design is so strong that the two realities fuse into one visual experience. • Gauguin shared a close and tempestuous friendship with Vincent Van Gogh. They were equally devoted to a life absorbed in painting, and the time they worked together in Arles in the late 1880s was highly productive for both artists. Portrait of Vincent painting Sunflowers, 1888 Gauguin’s and Van Gogh’s All-night café , Arles, 1888 • Gauguin boasted of the “great rustic and superstitious simplicity” of the figures in his paintings. He said “Civilization makes you sick”. Gauguin saw in peasant and “primitive” people an honesty and a connection to spirituality which lent itself perfectly to his particular brand of Symbolist painting. Proud of his Peruvian heritage, Gauguin saw himself as a modern day “primitive”; he drew heavily on non-western art for influence; and famously moved to live and work in Tahiti. • The Tahitian society was a strange mingling of paganism and Christianity and many of Gauguin’s paintings displayed the fusing of cultures both in their subject matter and in his use of modern western art ideas and ancient imagery. For example, his Ia Orana Maria (1891) has the Madonna and Child as Tahitians, attended by Buddhist angels derived from an ancient Buddhist temple frieze, so combining Christian, Buddhist and Oceanic religions • In many ways, Gauguin’s paintings became less “primitive” in the South Seas. His colour palette remained unnaturalistic but became more harmonious and sophisticated. He brought on his travels a stock of photographs and reproductions, from ancient Egyptian and Greek sculpture alongside examples from European painting, and his later work shows the breadth of these references. Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892) depicts Gauguin’s teenage lover, struggling to sleep for fear of Tupapau (the Spirit of the dead) lurking in the shadows. Gauguin’s version of Manet’s Olympia, makes use of a number of symbolist devices, from unnaturalistic colour to the presence of a supernatural being. •Gauguin wrote that the purple of the background was used to create a mood of “terror” and the yellow cloth was designed to be “unexpected”. The real and the imagined coexist, resulting in a highly emotionally charged image. The End Annah The Javanese, 1894, oil on canvas 116 x 81cm