THE PHOTIAN SCHISM (857-867)

advertisement

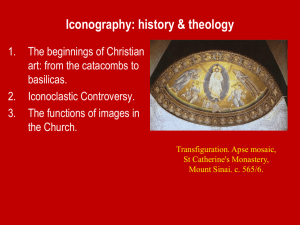

CHAPTER 7 Iconoclasm, The Carolingian Renaissance, And The Great Schism The communion between East and West was shattered in the Great Schism that separated two traditions with the same Sacraments. Iconoclasm, The Carolingian Renaissance, And The Great Schism From the fourth to the eleventh centuries the Church focused her energies on the conversion of the European peoples. However, during the eighth and ninth centuries, political and religious factors, coupled with language, cultural, and geographical differences drove the Church in the East and West further apart. Although they shared the same Sacraments, the rise of the patriarchs, questions of papal supremacy, liturgical and disciplinal differences, and the Iconoclastic Controversies pushed the East and West toward a final confrontation. PART I BYZANTIUM: THE LONG VIEW Byzantium was at one time the most important center of political, religious, cultural, and economic activity in the world of the former Roman Empire. The Byzantines were Roman in their laws, Greek in their culture, and Oriental in their habits. Constantinople was a center of learning, art, and architecture. Hagia Sophia, the cathedral of the Patriarch of Constantinople, is still regarded as a wonder of Byzantine art and architecture. PART I BYZANTIUM: THE LONG VIEW The Byzantium Empire lasted longer than the combined duration of the Roman Republic and Empire. Unlike the Roman Empire, Byzantium enjoyed the blessing of a wholly Christian orientation. Constantine the Great had established the city AD 330, and it lasted until 1453, when it fell to the Ottoman Turks. Muslim armies had already conquered three of the four great patriarchates (Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria). BYZANTINE CHRISTIANITY The numbers of Christians in Byzanatium exceeded those in Rome and the West. All of the cities to which Christianity first took hold were within the Byzantine Empire, and the original language of the New Testament was almost entirely Greek. Although Rome remained the location of the successor’s of St. Peter, it no longer enjoyed the influence that it had during the Roman Empire. Although the Pope was still the ultimate authority, the intimate relationship between the emperor and the patriarchs of Constantinople would come to overshadow the authority of the Pope. BYZANTINE CHRISTIANITY In the west, due to the absence of political communities, the Church came to be viewed as something that transcended all national boundaries or allegiances. However, in the east, missionary activity resulted in the creation of national churches. At times the influence of these national churches was strong enough to cause schisms within the Eastern Church. The political environment of the Eastern Empire gave rise to caesaropapism, in which the temporal ruler extended his authority to ecclesiastical and theological matters. Such emperors appointed bishops and the Eastern Patriarch, and were involved in directing liturgical practices. In time, the increasing power of the emperor put him in conflict with the authority of the Pope. EMPEROR JUSTINIAN I Justinian I succeeded in resurrecting the glories of the Roman Empire in the East. He is responsible for many advances in architecture, the fine arts, and civil law. However, his view that he was head of both the state and the Church led him into conflict with the papacy over the question of Monophysitism. MILITARY CAMPAIGNS In 553/4 Justinian I led a campaign against the Vandals. Not only did he defeat the Vandals, capturing their king, he freed Italy from the Ostrogoths, and secured most of Spain from the Visigoths. He succeeded in reconquering half of Europe and Northern Africa. CODEX JUSTINIANUS (529) Justinian I undertook the collection and systemization of all Roman law. He wanted to ensure a uniform rule of law throughout the entire empire, and sought to provide an ultimate reference for any legal question that might arise. His codex is an important basis for the development of Canon Law as well as for civil law in all of the countries of Europe. HAGIA SOPHIA (538) Under Justinian’s patronage grew a unique style of architecture which is now called Byzantine. The most famous work built under his reign is Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) in Constantinople, which is widely thought to be one of the most perfect buildings in the world. MONOPHYSITISM AND JUSTIANIAN Monophysitism, the belief that Christ possesses only one nature, and that his human nature was incorporated into the divine nature, was a troubling heresy during Justinian’s rule. The issue was supposedly resolved at the Council of Chalcedon (451) by Pope St. Leo I and St. Cyril. However, there remained some controversy and some Eastern Churches (now called “Old Oriental Churches”) refused to recognize the council. Justinian desired to reconcile the remaining Monophysites with the Church. When Pope St. Silverius was elected Pope, Justinian’s wife, who had Monophysite tendencies, sought to have him removed. Documents were forged purporting to prove the Pope’s betrayal of the empire, and Pope St. Silverius was sent into exile. Justinian I’s activity in the ecclesiastical sphere led to other abuses and constitutes the main flaw in an otherwise admirable reign. EMPEROR HERACLIUS: A PILGRIM IN JERUSALEM After Justinian I’s death, the empire fell into disarray, and the lands he had reclaimed were soon lost again. In 611, the king of Persia marched against Byzantium and finally overran Jerusalem with the help of 26,000 Jews who were eager to destroy Christian sovereignty in their city. Churches, Christian shrines, and monasteries were destroyed. Emperor Heraclius reached an agreement with the Patriarch of Constantinople, who funded the emperor’s army in order to liberate Jerusalem. In 629, this Byzantine Crusade culminated in the invasion of Persia and Heraclius, victorious, entered Jerusalem to venerate the relic of the True Cross. PART II The Iconoclastic Controversy (ca. 725-843) The Iconoclastic Controversy served as a breaking point between the Popes and the emperors, as they adopted permanent and adversarial positions regarding the use and veneration of icons. At times, the Popes had to seek protection from the Franks against the oppressive measures of dissenting emperors. ICONS An icon is a flat, two-dimensional picture of Christ, the Virgin Mary, or one of the saints. Icons were numerous in the East before the fifth century, and were used as aids for Christian acts of piety. Highly ritualized prayer involving bowing and the lighting of incense became the norm among the Christian faithful. The icon is seen as an invitation to prayer, and not as an object to worshiped. ICONS The word “iconoclast” literally means an “image breaker.” By the eighth century, abuses of icons had sprung up among the faithful, and many people believed that they had special powers. Many worshipers turned their attention to the icon itself, rather than the spiritual mysteries the icon was supposed to represent. A kind of idolatry, forbidden by the First Commandment, emerged from the incorrect use of icons. As a guard against idolatry, iconoclasts sought to destroy the icons, and purify the Christian religion. FIRST ICONOCLASM EMPEROR LEO III, THE ISUARIAN (717-741) Two to three centuries before Leo III, two forces were at work which would aid the cause of Iconoclasm. The Monophysite heresy, denying the humanity of Christ, objected that icons portrayed Christ’s humanity. Judaism and Islam, the other great monotheistic religions, prohibited the representation of God. Leo III, desiring unification in his empire, was convinced that the only issue preventing the conversion of Jews and Muslims was the use of icons. FIRST ICONOCLASM EMPEROR LEO III, THE ISUARIAN (717-741) Furthermore, he sought to appease those Christians with Monophysite leanings. In 726, Leo issued a decree that all icons were an occasion of idolatry, and ordered their destruction. The Pope, the Patriarch of Constantinople, and nearly all monks condemned this decree. The patriarch was deposed, hundreds of monks and nuns lost their lives, and many of the oldest icons in Byzantium were destroyed. Finally, Pope St. Gregory III convened two councils in Rome that condemned Leo’s actions, and excommunicated him. However Leo remained obstinate, and at the time of his death, iconoclasm was still in force, and the Eastern Church was no longer in communion with Rome regarding this matter. ST. JOHN OF DAMASCUS At a young age, St. John renounced his family’s wealth and became a monk in Jerusalem. There he wrote a great iconophile (Greek for “lover of icons”) work in favor of St. Gregory II and against Leo III. He also criticized all imperial interference in ecclesiastical matters. In his work The Fount of Wisdom, he explicates the teaching of the Greek fathers on all important doctrines of Christianity, defending the use of icons by reference to the Incarnation. In coming to world as the God-man, Jesus Christ, God implicitly gave permission for the depiction of Christ’s human form in art. Considered the last of the Eastern Church Fathers, St. John of Damascus was made a Doctor of the Church. CONSTANTINE V (741-775) Constantine V sought to strengthen his position against icons by gaining the support of the Greek Church. He carefully orchestrated the Council of Hiereia (754), which delivered the results that he sought. He not only excluded Rome, but the ancient patriarchies of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria, all of whom were iconophiles. The monks continued to oppose him, and they were met with exile, imprisonment, and sometimes death. At least 300 monks were put to death for the Faith. ICONOPHILE RECOVERY: THE SEVENTH ECUMENICAL COUNCIL: THE SECOND COUNCIL OF NICAEA(787) The next emperor, Leo IV, did not enforce, although he did not repeal, the iconoclastic measures. When he died, his wife, the Empress Irene, took control of the empire for their son. She had Catholic sympathies, and persuaded Pope Adrian I to convene the Seventh Ecumenical Council, the Second Council of Nicaea. ICONOPHILE RECOVERY: THE SEVENTH ECUMENICAL COUNCIL: THE SECOND COUNCIL OF NICAEA(787) The Pope sent two legates with written condemnations of iconoclasm, and the Patriarchs of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria, not permitted to attend by their Muslim rulers, each sent two monks in their stead. The Council ruled in favor of the papal teaching regarding the veneration of icons. It went on to distinguish two types of adoration: An icon may be venerated through acts of respect and honor, However, God alone is worthy of adoration. SECOND ICONOCLASM (815-843) In 811, the Bulgar leader killed the Byzantine Emperor. Two years later the Byzantine military staged a coup and Leo V became emperor. Many in Byzantium’s upper society and military had remained iconoclastic. As a result, Leo V and his successors reinstated iconoclasm. He deposed the Patriarch of Constantinople and appointed his own patriarch, who summoned a council restoring the findings of the Council of Hiereia. When several of the bishops opposed him, Leo V revived the persecutions. FEAST OF THE TRIUMPH OF ORTHODOXY (843) Empress Theodora reversed the trend of iconoclasm by deposing the iconoclastic Patriarch of Constantinople. Under the new Patriarch Methodius, the iconoclastic bishops were deposed and replaced by iconophiles. The first Sunday of Lent was named the Feast of the Triumph of Orthodoxy to celebrate the triumph of icons. Finally, in 843, the barren walls of churches were again decorated with beautiful icons, and the orthodox practice of venerating icons was secure. PART III The Rise of the Carolingians and an Independent Papacy During the Iconoclastic controversies, the Papacy often looked to the Western Franks for protection against the Byzantine Emperors. The Franks conversion and rise to power provided the West with a semblance of political unity and relatively stable support for the Church. The alliance between the two would culminate with the crowning of Charlemagne as Emperor AD 800. THE ORIGIN OF THE CAROLINGIAN LINE The Merovingian Dynasty had ruled the Franks since the time of Clovis. However, their control was nominal due to corruption and incompetence. Since the end of the seventh century, the real power lay with the Carolingians, named for Charles Martel. Pepin the Short, son of Charles Martel, defeated the Muslims at tours AD 732. Pepin consolidated his power by requesting that the Pope give him kingship over the Franks. The Pope granted this power, making the Carolingian dynasty the rightful rulers, and successfully transferring power from the Merovingians. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PAPAL STATES Pope Stephen II expected protection from Pepin in exchange for papal support of the Carolingians. The Lombards were threatening Rome and the Byzantines did not intend to protect them. The Pope anointed Pepin and his sons, threatening to condemn anyone who disobeyed them. This showed that the Church could bestow secular authority on kings. Pepin in turn agreed to intervene on behalf of the Pope before the Lombard threat. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PAPAL STATES Pepin successfully defeated the Lombards, securing lands for the papacy that would come to be known as the Papal States. For the first time the Pope became both a spiritual and temporal leader. The Papal States protected the papacy from temporal and ecclesiastical interference. However, they also suffered from the same temptations that beset those in political authority. CHARLEMAGNE (REIGNED 769-814) Charles, son of Pepin, had a long reign devoted to securing and expanding his kingdom, and by the time of his death he had unified most of Western Europe under one Christian ruler. Charles, known as the “Great,” (Carolus Magnus in Latin) was a powerful and charismatic ruler, combining military skill with political astuteness. His public policy was explicitly Christian, and his ecclesiastical and civil reforms helped European culture. His civic legislation was based on Canon Law, and he considered decrees of synods and councils as binding on his subjects. CHARLEMAGNE (REIGNED 769-814) Acting in the interest of the Church, he reformed the clergy, established new dioceses, and raised funds to support worship and the priests. A devout Catholic, he observed the times for prayer and fasting, and attended liturgical ceremonies. He sang in the choir and read the Bible daily. CHARLEMAGNE’S RELATIONSHIP TO THE PAPACY When the Lombards once again threatened Rome, Charlemagne came to the defense of the papacy. Entering Rome as a hero, he prostrated himself before the Pope and was given the title “Patrician of Rome.” He made himself king of the Lombards, uniting all Germanic peoples. When the Roman nobility charged Pope St. Leo III with conspiracy and corruption, Charlemagne came to Rome to investigate. With the help of Charlemagne, St. Leo was able to escape the machinations of the Romans. CHARLEMAGNE CROWNED EMPEROR (800) After his trial, Pope St. Leo III crowned Charlemagne as emperor during the Christmas day Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica in 800. This coronation placed Charlemagne in direct line of descent from the old Roman Empire, and the Germans were finally incorporated into Roman civilization. These actions infuriated the Byzantine emperors, who still considered themselves as the rightful imperial rulers in the West. They felt the West was now ruled by a barbarian, and refused to recognized the legitimacy of this newly formed empire, but because of Charlemagne’s power and influence, they eventually had to recognize him, referring to him as King of the West. CHARLEMAGNE AND THE SAXONS For years the Saxons resisted conversion to Christianity. They would seemly convert, only to rebel and kill Christians. Charlemagne felt he had no other choice than to force their conversion by the sword. To this end, he was extremely harsh, and at one point ordered the beheading of four thousand men. This exemplifies Charlemagne’s weakness as a ruler. He considered any infraction of the Church’s teaching as a crime, and the disproportionate punishment often contradicted the true meaning of the Gospel. He also made liberal use of capital punishment. Under his rule any of the following merited death: killing a priest, belonging to a heathen group, stealing, eating meat on Friday, refusing to fast, refusing Baptism, or cremating a body. THE CAROLINGIAN RENAISSANCE When Charlemagne came to power, learning was on the decline in the West. Charlemagne emphasized the importance of education and artistic excellence, and commanded that every monastery have a school. Due to his efforts, the clergy were better educated in classical and biblical texts than they had been for several hundred years. This improved literacy led to a renewed enthusiasm for the Catholic Faith and paved the way for a new wave of missionary activity. ALCUIN, CAROLINGIAN SCHOLAR Born in Northumberland and educated at York, Alcuin was the best and most influential scholar of the Carolingian Renaissance. He joined Charlemagne’s court to participate in the new spirit of learning and eventually retired in France as the Abbot of St. Martin’s monastery in Tours. His scholarly work included a variety of texts covering the Bible and theological tradition, as well as Latin grammar and mathematical tracts. He oversaw the production of the Tours Bible. He had a keen interest in the liturgy, revising the Roman Lectionary and the Gregorian Sacramentary. PART IV The Great Schism Although the seed of division had been planted by Constantine in the Fourth Century, the alienation intensified due to the Iconoclastic Controversy and Charlemagne’s rise to power. By the eleventh century the relationship was very tenuous, and the final shattering of their communion occurred AD 1054. THE EMERGENCE OF DIFFERENCES Different conceptions of Church government and hierarchy caused a growing distance between East and West. The Bishop of Rome had a dual jurisdiction in the Church: the Latin West, centered in Rome, as well as the universal Church. As Constantinople grew in power, it tightened its grip over the other ancient centers of Christianity in Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem. The Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451 recognized these centers, along with Rome, as especially ancient and important centers of Christianity. For political and theological reasons, the Christians of the East tended to minimize the importance of the Pope as chief shepherd of the Church, and seldom referred to the Pope, except in extreme cases. THE EMERGENCE OF DIFFERENCES Eastern Christians were much more closely aligned with their National Patriarch than with the Bishop of Rome. In addition, caesaropapism was a cause of tension. The emperors played an important role in the Eastern Church, and played a major role in each of the five schisms that occurred between 325 and 825. Finally, the relationship between the laity and the religious was different in the East and the West. In the West, the monks worked very closely with the people, while in the East, the monks were secluded and had little contact with the laity. LITURGICAL PRACTICES OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES There are two types of Eastern Churches: Catholic and Orthodox. The Eastern Catholic Churches are in union with Rome, while the Eastern Orthodox Churches are not. The liturgical rites practiced in both of these Churches are based on the practices of the Apostles and Fathers of the Church. Because Greek was the common language in the East, it became the liturgical language of the Church, and the vernacular was adopted by the National Churches. This is exemplified by the missionary activity of Sts. Cyril and Methodius when they translated the Bible and the liturgical texts into the native language of the Slavs. LITURGICAL PRACTICES OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES Over time, the West incorporated Latin and more Roman customs, while the Eastern liturgy remained Greek. There are two types of musical traditions in the East: Byzantine and Russian. The Byzantine is sung a cappella, while the Russian (although based on the Byzantine) incorporates western scales. Another difference is the Sign of the Cross. In the east the thumb, forefinger, and middle finger are brought together symbolizing the Triune God and the two natures of Christ. The “horizontal” beam of the cross is traced right to left, the opposite direction as in the West. THE FILIOQUE CONTROVERSY Beginning in the Third Council of Toledo in 589, the words “and the Son” were added to the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed. By 800, this formulation of the Creed was standard in the West. The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed was developed against those who denied that the Holy Spirit came from the Father, and was never meant to be interpreted that the Holy Spirit did not also come from the Son. The “Filioque” clause was simply meant to clarify the original meaning. However, the Patriarch of Constantinople refused the addition to the Creed, and it is has not been accepted by the Eastern Orthodox Churches to this day. THE PHOTIAN SCHISM (857-867) When the Patriarch of Constantinople refused Holy Communion to a high ranking government official due to rumors regarding an adulterous affair, he was deposed by the emperor, who elevated another to the position. When the rightful patriarch refused to step aside, the emperor and his “new” patriarch, Photius, appealed to the Pope. When the Popes legate’s decided in favor of the emperor, after being bribed, the Pope had them excommunicated, and then ruled in favor of the deposed patriarch. This infuriated the emperor and Photius, who tried to stir up unrest against the Pope, in particular in regard to the filioque clause, and German missionaries in Bulgaria. THE PHOTIAN SCHISM (857-867) Later, when the Pope refused to recognize a Bulgarian Patriarchate, the Bulgarian Church turned to Constantinople. Photius was removed, but years later was legitimately elected as Patriarch of Constantinople. He once again renewed his campaign against the Pope, excommunicating the entire Latin Church for “liturgical irregularities” and their alteration of the Creed. Although many Eastern bishops disagreed with him, they could not resist his influence. Photius was finally deposed and reunion with Rome was restored, but his dissension had struck deep roots among the Greek people and would resurface later. THE GREAT SCHISM (1054) The final split between Eastern and Western Christianity occurred in 1054. The disputes over the Filioque Clause, the crowning of Charlemagne, the issues of authority raised by Photius, and the reforming tendencies of the Popes, all came into focus. Further, Byzantium had increased its military strength, and wanted a greater degree of independence from the West. These circumstances shattered the 1000 year communion between East and West. PATRIARCH MICHAEL CERULARIUS Before becoming partriarch, Michael Cerularius had lived in the seclusion of an Eastern monastery that had been influenced by Photius. Upon becoming patriarch, his anti-Latin tendencies grew, and the target of his attacks was the Pope. He objected to a celibate priesthood, the Saturday fast, the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist, beardless priests, eating meat with blood, and omitting the alleluia in Lent. He closed all of the Latin parishes in Constantinople and their consecrated hosts were trampled on. PATRIARCH MICHAEL CERULARIUS Cardinal Humbert was sent by the Pope to deal with the situation. He made it plain to the patriarch that the Pope held primacy in the Church. His statement to the patriarch was, “Either be in communion with Peter or become a synagogue of Satan,” at which point the patriarch deleted the Pope’s name from all liturgies. Two papal legates later sent by the Pope were equally disastrous. Due to their lack of diplomatic skill and arrogance, they enabled the patriarch to turn the population of Constantinople against them and against Rome. THE ACTUAL SCHISM On July 16, 1054, Cardinal Humbert attended the Divine Liturgy at Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. There he denounced the patriarch for refusing papal authority and laid a document of excommunication on the high altar. Technically, the papal legates did not have this authority as the Pope had just died. The Easter emperor wanted to heal the rift and called for reconciliation, but the patriarch incited riots. Not wanting a civil war, the emperor backed down. The documents of excommunication were burned by the patriarch, and a council in Constantinople excommunicated the Pope. THE ACTUAL SCHISM Since that time, the Patriarch of Constantinople has been known as the “Ecumenical Patriarch” of the East, and is regarded as the first among equals among the Eastern Patriarchs. In 1965, before the closing Mass of the Second Vatican Council, the Pope and patriarch participated in a show of reconciliation, expressing regret over the mutual excommunications. CONTEMPORARY EFFORTS TO HEAL THE SCHISM Pope John Paul II made great efforts to reach out to the Eastern Church. He opened dialogues that may some day ultimately heal the schism. He called for Christians “to work ever more fervently for the unity which is Christ’s will,” calling division a sin before God and a scandal before the world. CONCLUSION During this period two distinct forms of Christianity came into being. While the East was locked in the Iconoclastic Controversy, the West found unity under the leadership of the Franks and the Popes. The Great Schism shattered Christianity, which has remained divided to this day. From the perspective of the Catholic Church, the major difference between East and West is the teaching authority and jurisdiction of the papacy as established by Christ through his Apostle St. Peter. The End