The French Arthurian..

advertisement

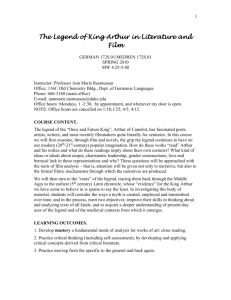

Artus: The French Arthurian Legend Mike Howells Historical Context of the Arthurian Legend Did King Arthur exist? “The only honest answer is, ‘We do not know, but he may well have existed.’” -Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson Historical Context of the Arthurian Legend On the basis of several historical documents we can conclude that an Arthur probably did exist: Welsh elegy Gododdin Nennius’ Historia Brittonum Annales Cambriae Right: Page from the Annales Cambriae, including entries for the battles of Badon and Camlann. Left: Arthur and Mordred clash at the battle of Camlann (Snyder 72-73) Historical Context of the Arthurian Legend The “Arthur Story” has existed in the form of local legends since at least as early as the 9th century. Appears in late 11th and early 12th century Latin Lives of Welsh Saints as a king or chief, “usually troublesome to the saint at first but afterwards overcome by a miracle.” (Jackson) The Legend of Arthur We see Arthur as a central figure in British and Irish mythology by the 11th century By the 12th century, Arthur has become a popular literary and legendary figure in Western Europe. “Why this exaltation of an alien king and court by the most sophisticated men of letters of Western Europe, men who, so far as one can tell, had not the slightest incentive to popularize a figure of so remote a time and people?” (Loomis) Why? (But first, why not?) Could not have been due to visits to the British mainland by European writers. Lack of intimacy with British settings Could not have been due to export of Celtic manuscripts. They would have been unreadable outside of Brittany. Could not have been due to foreign-language books by Welsh natives. Even the most influential works (Geoffrey of Monmouth) made little impression on verse romances. Diffusion of The Matter of Britain The Matter of Britain is the name given to the body of literature associated with Britain and Brittany. It includes, but is not limited to, the Arthurian legends. The twelfth century French poet Jean Bodel created the name in a poem entitled Chanson de Saisnes: Ne sont que iij matières à nul homme atandant, De France et de Bretaigne, et de Rome la grant. Crossing the Channel Wales was not the only Celtic territory which possessed an Arthurian tradition. Cornwall also retained strong ties to the Arthur legend. As the Anglo-Saxon presence in Britain grew more extreme, some Celtic peoples migrated from Cornwall across the English Channel to Brittany. Source: Atlas of Medieval Europe, Angus Konstam Bretonese References to Arthur Early Bretonese Arthur references: The Life of Goeznovious • Mentions the victories of Arthur. The Life of St. Efflam • Represented by a sculpture in Perros which depicts a figure with a crozier (Efflam) and a figure with a shield (Arthur) lying exhausted next to a dying dragon. Map of Brittany (Synder 99) Other Early References: 1085 - William of Malmesbury refers to Arthur in his Historia Regum Anglorum; “He is that Arthur about whom the trifles of the Bretons (nugae Britonum).” 1115 - Reference to the Round Table in Wace’s Brut; “…Of which Britons tell many stories.” 1216 – Welshman Giraldus Cambrensis “attributes to the ‘fabulosi Britones’ the story of Arthur’s transportation by a certain imaginary goddess, named Morganis, to the island of of Avalon for the healing of his wounds.” (Loomis) Crucial in these passages is the recurring reference to Arthur as Britones. By this point in history Arthur has become a Breton, distinct from Cambrenses (Welsh) and Cornubienses (Cornish). Arthur Legends in France Wace Marie de France The Romance of Tristan Thomas version Beroul version Chretien de Troyes Illustration from a 15th century manuscript of Lancelot. (Synder 6-7). Wace Roman de Brut Translation of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae. • More than just a straight translation Omitted some elements and abridged others. Wove fictional elements into his narrative, including oral tales. First to mention the Round Table. “For the noble barons he had, of whom each felt that he was superior--each one believed himself to be the best, and no-one could tell the worst--King Arthur, of whom the Britons tell many stories, established the Round Table. There sat the vassals, all of them at the table-head, and all equal. They were placed at the table as equals. None of them could boast that he was seated higher than his peer.” First to refer to Arthur’s sword as Excalibur. Adapted from Geoffrey’s name for it, “Caliburn.” A 14th century manuscript of the Roman de Brut. (Snyder 88) Chretien de Troyes Responsible for creating several Arthurian mythic elements The Holy Grail • In Perceval (Le Conte du Graal) Camelot Lancelot • First appears in his poem Erec, • Appears more fully in Le Chevalier de la Charrette ‘Lancelot slays a dragon’, by Arthur Rackham. The Romance of King Arthur. (Snyder, 105) Marie de France A French poetess of the twelfth century. Probably lived in England in the court of Henry II. 1160 - Lais Twelve verse narratives in French, including two directly referencing Arthurian legend. • Lanval • Chevrefoil The Romance of Tristan Two versions written Thomas version written in 1165 • Considered the “courtly” version due to refined language and tamer action Beroul version, written between 1160 and 1190 • Bloodier and more visceral than the Thomas version, but sole existing manuscript is much more fragmented. Tristan and Isolde, from a 14th century manuscript. (Snyder 99) In conclusion… Monty Python LEGO 2001 Ifilm, LEGO studios and Python (Monty) Pictures