Lecture Powerpoint

advertisement

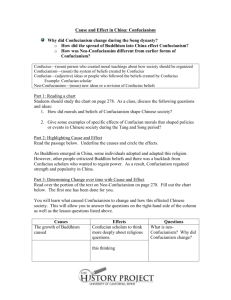

Neo-Confucianism in Traditional Chinese Thought (compiled/edited by Fred Cheung, 2010) [Main source: John King Fairbank, et al., eds., East Asia The Great Tradition.] • In traditional Chinese thought, the late T’ang and Sung Dynasties of China witnessed the appearance of patterns that were to remain characteristics of China until the 19th century. The philosophical/intellectual synthesis (of Taoism, Buddhism into Confucianism), known as NeoConfucianism, which emerged from the intellectual ferment of these centuries was to be almost unchanging core of Chinese thought from then until its collapse under the impact of western thought and revolutionary political and social changes in the 20th century. • Two basic factors lay behind the revived interest in Confucian philosophy. One was the turning inward of the Chinese during their long losing battle with the northern barbarians. In the early T’ang the Chinese, confident in their power, were inquisitive and tolerant toward the outside world. • When the first ambassadors from the Islamic caliphate came to China in 713 and refused on religious grounds to prostrate themselves before the emperor in the traditional kowtow, the Chinese court readily waived the requirement. By the late T’ang, however, a growing fear and resentment of the barbarians became evident. • The other reason for restored interest in Confucianism was the obvious success of the old Chinese political ideal. The political disillusionment of the Six Dynasties period (3rd to 5th centuries) had now receded into dim past. The need for an educated officialdom in the revived bureaucratic state had led to the recreation of the examination system and a reemphasis on the Confucian Classics on which the examinations focused. • Confucian ideas, concepts, and thoughts had never died out even at the height of the Buddhist influence at the T’ang court, but soon, a new kind of synthesis of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism grew steadily in strength and popularity. • The Neo-Confucians hoped to recapture the original vision – to recreate the ideal Confucian society that they believed had existed in ancient times – but they did so in terms of the attitudes and interests of their own days. • The Neo-Confucian thinkers were strongly influenced by some the Buddhist concepts that had been so important in Chinese thought for the past few centuries. • Many of them had been students of Buddhism or Taoism before they turned to Neo-Confucianism, and some even lived in Zen (Ch’an) monasteries. Buddhism had conditioned men to think in metaphysical terms, and one of the things that was new about Neo-Confucianism was that it developed a metaphysics for Confucianism, using Buddhist ideas and Taoist terminology. • The 11th and 12th centuries were the period of great philosophical ferment, when different schools of Neo-Confucian thoughts appeared. For instance, Lu Chiu-yuan (or Lu Hsiang-shan, 1139-1192) developed a Zen-like emphasis on personal intuition that was to reach its height under the Ming Dynasty. • Another famous Neo-Confucian was Chou Tun-i (1012-1073), who took from the Classic of Changes (I Ching) the term T’aichi, or supreme ultimate, and devised a cosmological chart (calendar) showing how yin and yang and the five elements derived from it. • The brothers Ch’eng Hao (1031-1085) and Ch’eng I (1032-1107) elaborated this metaphysics. Ch’eng I was also responsible for selecting the Mencius, the Great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, and the Analects to form the (Classics of) Four Books, which became thereafter the main scriptures of Confucianism and the core texts for traditional Chinese education. • The final synthesizer and architect of Neo-Confucianism at this time was Chu Hsi (1130-1200), who was claimed to be the successor of the Confucian Orthodoxy of Mencius (even though after so many centuries). • Chu Hsi was also a great historian, philosopher, and commentator on the Confucian Classics. In the NeoConfucian metaphysics of Chu Hsi’s school, all varieties of things were thought to have their respective li, or fundamental principles of form, and their ch’i, literally ether, or what we might call matter. • The influence of Buddhist concepts is obvious. The Sung Neo-Confucians were close enough to Buddhism to put emphasis on metaphysics, and they carefully elaborated the relationship between the supreme ultimate, yin and yang, and the five elements, and developed cyclical theories of change of Buddhist ideas. • The old conflict between Mencius’ belief that man is by nature good and thus only needs education and self-development versus Hsun Tzu’s view that man is by nature evil and thus needs strict control, came to the study again, but Chu Hsi succeeded Mencius and confirmed Mencius orthodoxy. • Chu argued that man’s nature is pure and good. It is the origin of the five basic virtues (benevolence, uprightness, propriety, knowledge, and reliability). It only needs polishing, thus, education is vital, though self-cultivation (Taoist/Buddhist) is also important. • The emphases of the Sung NeoConfucianism were essentially those of Mencius/Chu and of the scholarbureaucrats of Sung China. After Chu’s death, his Neo-Confucian synthesis gradually became established as the orthodoxy. By 1313, Chu’s Commentaries on the Classics had been made the standard texts to which all answers in the civil service examination had to conform.