Commitment to In-group Narrative

advertisement

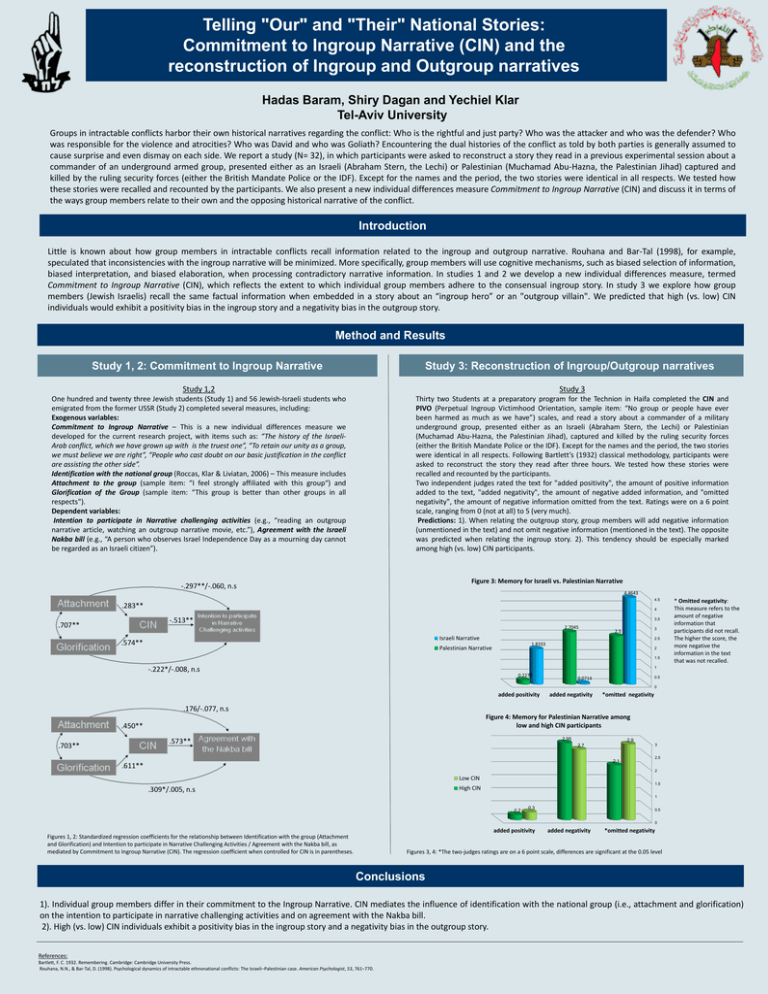

Telling "Our" and "Their" National Stories: Commitment to Ingroup Narrative (CIN) and the reconstruction of Ingroup and Outgroup narratives Hadas Baram, Shiry Dagan and Yechiel Klar Tel-Aviv University Groups in intractable conflicts harbor their own historical narratives regarding the conflict: Who is the rightful and just party? Who was the attacker and who was the defender? Who was responsible for the violence and atrocities? Who was David and who was Goliath? Encountering the dual histories of the conflict as told by both parties is generally assumed to cause surprise and even dismay on each side. We report a study (N= 32), in which participants were asked to reconstruct a story they read in a previous experimental session about a commander of an underground armed group, presented either as an Israeli (Abraham Stern, the Lechi) or Palestinian (Muchamad Abu-Hazna, the Palestinian Jihad) captured and killed by the ruling security forces (either the British Mandate Police or the IDF). Except for the names and the period, the two stories were identical in all respects. We tested how these stories were recalled and recounted by the participants. We also present a new individual differences measure Commitment to Ingroup Narrative (CIN) and discuss it in terms of the ways group members relate to their own and the opposing historical narrative of the conflict. Introduction Little is known about how group members in intractable conflicts recall information related to the ingroup and outgroup narrative. Rouhana and Bar-Tal (1998), for example, speculated that inconsistencies with the ingroup narrative will be minimized. More specifically, group members will use cognitive mechanisms, such as biased selection of information, biased interpretation, and biased elaboration, when processing contradictory narrative information. In studies 1 and 2 we develop a new individual differences measure, termed Commitment to Ingroup Narrative (CIN), which reflects the extent to which individual group members adhere to the consensual ingroup story. In study 3 we explore how group members (Jewish Israelis) recall the same factual information when embedded in a story about an “ingroup hero” or an "outgroup villain". We predicted that high (vs. low) CIN individuals would exhibit a positivity bias in the ingroup story and a negativity bias in the outgroup story. Method and Results Study 3: Reconstruction of Ingroup/Outgroup narratives Study 1, 2: Commitment to Ingroup Narrative Study 1,2 Study 3 One hundred and twenty three Jewish students (Study 1) and 56 Jewish-Israeli students who emigrated from the former USSR (Study 2) completed several measures, including: Exogenous variables: Commitment to Ingroup Narrative – This is a new individual differences measure we developed for the current research project, with items such as: “The history of the IsraeliArab conflict, which we have grown up with is the truest one”, “To retain our unity as a group, we must believe we are right”, “People who cast doubt on our basic justification in the conflict are assisting the other side”. Identification with the national group (Roccas, Klar & Liviatan, 2006) – This measure includes Attachment to the group (sample item: “I feel strongly affiliated with this group“) and Glorification of the Group (sample item: “This group is better than other groups in all respects"). Dependent variables: Intention to participate in Narrative challenging activities (e.g., “reading an outgroup narrative article, watching an outgroup narrative movie, etc.”), Agreement with the Israeli Nakba bill (e.g., “A person who observes Israel Independence Day as a mourning day cannot be regarded as an Israeli citizen”). Thirty two Students at a preparatory program for the Technion in Haifa completed the CIN and PIVO (Perpetual Ingroup Victimhood Orientation, sample item: “No group or people have ever been harmed as much as we have”) scales, and read a story about a commander of a military underground group, presented either as an Israeli (Abraham Stern, the Lechi) or Palestinian (Muchamad Abu-Hazna, the Palestinian Jihad), captured and killed by the ruling security forces (either the British Mandate Police or the IDF). Except for the names and the period, the two stories were identical in all respects. Following Bartlett’s (1932) classical methodology, participants were asked to reconstruct the story they read after three hours. We tested how these stories were recalled and recounted by the participants. Two independent judges rated the text for "added positivity", the amount of positive information added to the text, "added negativity", the amount of negative added information, and "omitted negativity", the amount of negative information omitted from the text. Ratings were on a 6 point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Predictions: 1). When relating the outgroup story, group members will add negative information (unmentioned in the text) and not omit negative information (mentioned in the text). The opposite was predicted when relating the ingroup story. 2). This tendency should be especially marked among high (vs. low) CIN participants. Figure 3: Memory for Israeli vs. Palestinian Narrative -.297**/-.060, n.s 4.4643 4.5 .283** 4 -.513** .707** 3.5 2.7045 3 2.5 Israeli Narrative .574** 2.5 1.8333 Palestinian Narrative 2 1.5 -.222*/-.008, n.s * Omitted negativity: This measure refers to the amount of negative information that participants did not recall. The higher the score, the more negative the information in the text that was not recalled. 1 0.2273 0.5 0.0714 0 added positivity added negativity *omitted negativity .176/-.077, n.s Figure 4: Memory for Palestinian Narrative among low and high CIN participants .450** 2.95 .573** .703** 2.9 3 2.7 2.1 .611** 2.5 2 Low CIN 1.5 High CIN .309*/.005, n.s 1 0.2 0.3 0.5 0 added positivity Figures 1, 2: Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between Identification with the group (Attachment and Glorification) and Intention to participate in Narrative Challenging Activities / Agreement with the Nakba bill, as mediated by Commitment to Ingroup Narrative (CIN). The regression coefficient when controlled for CIN is in parentheses. added negativity *omitted negativity Figures 3, 4: *The two-judges ratings are on a 6 point scale, differences are significant at the 0.05 level Conclusions 1). Individual group members differ in their commitment to the Ingroup Narrative. CIN mediates the influence of identification with the national group (i.e., attachment and glorification) on the intention to participate in narrative challenging activities and on agreement with the Nakba bill. 2). High (vs. low) CIN individuals exhibit a positivity bias in the ingroup story and a negativity bias in the outgroup story. References: Bartlett, F. C. 1932. Remembering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Rouhana, N.N., & Bar-Tal, D. (1998). Psychological dynamics of intractable ethnonational conflicts: The Israeli–Palestinian case. American Psychologist, 53, 761–770.