Powerpoint - Central Baptist Theological Seminary

advertisement

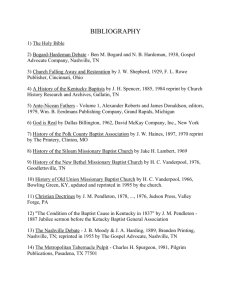

“Standing Firm” Lecture Two: Early Opposition to Liberalism Where We’re Going Nineteenth Century Northern Baptist opposition. The Bible Conference movement. Controversy in the Grand Rapids Baptist Association. The Founding of Northern Baptist Theological Seminary. The Fundamentals: A Testimony for the Truth. 19th Century, Northern Baptists Opposition to liberalism became evident during the 1880s. 1882, a review by O. S. Stearns in the Baptist Quarterly Review. 1883, an address by Alvah Hovey at the Baptist Autumnal Conference. 1883, an article by Howard Osgood in the Baptist Quarterly Review. 1883, an article by P. S. Evans in the Baptist Quarterly Review. The focus was primarily upon destructive higher criticism. The tone was concessive, with the objectors hoping that further study would vindicate the traditional approach. George William Lasher Editor of the Journal and Messenger from 1876 until his death in 1920. Involved in the controversy over Crawford Howell Toy in 1878. Supported the firing of Ezra Gould in 1881. Criticized William Newton Clarke. Opposed both William Rainey Harper and George Burman Foster at Chicago. Personal friend of Walter Rauschenbusch, but vigorous opponent of Rauschenbusch’s social gospel. Significant Controversies 1892 at the Baptist Autumnal Conference. T. A. T. Hanna spoke for biblical inerrancy, D. G. Lyon and J. B. G. Pidge downplayed it. Howard Osgood and J. W. Wilmarth came in on Hanna’s side, but Nathaniel Schmidt supported Lyon and Pidge. Ezekiel Robinson opposed Hanna and Osgood by name. Hanna’s (rather heated) reply was dismissed with hisses. 1895 in the Baptist Quarterly Review. Normal Fox expressed liberal views, aroused a strong backlash. Several participated in the exchange, notably Heman Lincoln and George D. B. Pepper. The Moderate Party Some of the moderates held liberal theology, but most were conservatives. The moderates saw liberalism as a mistake but not a threat. Their real concern was that the denominational program would suffer in any conflict between conservatives and liberals. The moderate tactic was to push for breadth and toleration. This tactic played directly into the hands of the liberals: they were happy to tolerate conservatives because they needed conservative money. Eri Hulbert, Moderate Example Hulbert was a transitional figure and dean at UCDS. “If the old and the new are to fight it will be a fight all along the line, among pastors, between schools, in churches, associations, conventions, national societies. It will extend to our young people, seminaries, mission fields, religious press, to all our organized denominational activities. . . . If both parties are to invite and keep up a satanic spirit Satan will deservedly get them both in the end, and, perforce, the denomination will go to the devil.” “The Baptist Outlook” in The English Reformation (Chicago, 1909). The Bible Conference Movement Began with six men meeting at E. P. Goodwin’s church in Chicago, 1875. “The Believers’ Meeting.” Met annually. Two concerns: premillennialism and liberal theology. Led to great, stand-alone prophecy conferences (New York 1878, Chicago 1886). Produced dozens of annual Bible conferences (Niagara, Seacliff, and others). Eventually gave birth to the Bible schools and the faith missions. Adoniram Judson Gordon Leader in the Believers’ Meeting for Bible Study. Pastor of Clarendon Street Baptist Church, Boston. Editor and publisher of the Watchword. Edited two hymnals, wrote music for fifteen hymns (“My Jesus, I Love Thee”). An Opponent of Liberalism Wrote against liberalism continuously in the Watchword. Board member at Newton, participated in firing Ezra Palmer Gould (1882). Organized the “Baptist Pastors’ Conference for Bible Study” in Brooklyn, 1890. Key rally against liberalism. Started the Boston Missionary Training School (now Gordon College) to train lay workers; the Bible institutes became an alternative to the seminaries as liberalism grew. Was deeply involved in the faith missions movement, which provided an alternative to liberal denominational missions. Liberalism Is the Easy Path: “You never find men backsliding into Orthodoxy.You never find men drifting into high Calvinism. And you never will till you find water running up hill and iron floating upward in air. On the contrary, one has to climb to get into this kind of faith, trampling on pride and self-esteem, and holding himself rigidly up to that conviction which is hardest to receive, that human nature is naturally depraved and needing regeneration, and that God is righteously holy and must punish sin.” A. J. Gordon, Watchword (May 1880), 141. Transition Years Gordon died in 1895. Most conservative leaders passed away within a few years of his death. It took time for new leadership to consolidate. During the transition, liberalism was able to gain a stronger foothold. The Northern Baptist Convention was organized during the transition, providing liberals with a new platform. The Great War begin in 1914, occupying conservative attention until its end. Three events during the transition period set the stage for the controversy that would begin in 1919. The Grand Rapids Controversy 1909 – Oliver W. Van Osdel accepted the pastorate of Wealthy Street Baptist Church in Grand Rapids. Fountain Street Baptist Church was pastored by Alfred W. Wishart, a notoriously outspoken modernist. The Grand Rapids Baptist Association could find no way to disfellowship Wishart or Fountain Street. Van Osdel led 14 of the 16 churches to withdraw and to begin a new association, the Grand River Valley Baptist Association. The Michigan Convention From the beginning, the state convention sided with Fountain Street. Convention officials actively worked to keep Van Osdel’s sympathizers out of Michigan pulpits. Convention officials tried to influence minorities to claim the property of GRVBA churches, leading to court cases. At one point, convention officials actually threatened to attempt to seize the Wealthy Street properties. The GRVBA Van Osdel edited the Baptist Temple News, which became the unofficial voice for the Grand River Valley group. He used it as a voice against liberalism and conventionism. The GRVBA employed its own church planting missionary and began starting churches across western Michigan. Eventually, the association outgrew the Grand River Valley. In 1920 it renamed itself the Michigan Orthodox Baptist Association. Also in 1920, tensions came to a head, with the Michigan Convention expelling the MOBA as a body. The MOBA The MOBA flourished as a separate body. Eventually renamed itself the Grand Rapids Association of Regular Baptist Churches. During the 1930s it led in organizing a statewide association of Regular Baptists. Due to its influence, Regular Baptist churches came to outnumber convention churches in the state of Michigan. Northern Seminary Background Many Baptists in Illinois were reacting against the liberalism of the University of Chicago. 1906 – the Ministers’ Council of the Chicago Baptist Association voted to censure George Burman Foster. The censure provoked a protest from university sympathizers. Foster himself continued to write and teach. 1908 – the Ministers’ Council voted to remove Foster from its fellowship. Illinois Baptists felt the need for a seminary to counteract the influence of the UCDS. Northern Seminary Organization Second Baptist wanted a seminary, but John R. Straton left the pastorate. Henry Mabie of the ABHMS also wanted to see the seminary organized. Mabie encouraged Second Baptist to call John Marvin Dean, then encouraged Dean to go. Mid-1912. Dean, a strong organizer and promoter, was the key figure in founding Northern, which opened in 1913. First student was Amy Lee Stockton, a female evangelist from California. Trajectory of Northern Organized in reaction against liberal theology. From the beginning, determined to work within NBC. Chicago sympathizers resisted recognition, Northern had to promise loyalty. Doubled down on the promise in view of the New World Program of 1919-1920. Hoped to gain funding. President Charles W. Koller built a strong, conservative faculty, but remained loyal to the NBC into the 1940s. Eventually the school capitulated to various forms of nonconservative theology; evangelical left to ecumenical right. Notable Northern Faculty Charles W. Koller, famous for his method of preaching. William Fouts, Old Testament. Julius R. Mantey, co-author of a widely used Greek syntax. Peder Stiansen, church historian and dean. Farris Whitesell, practical theology. Carl F. H. Henry (mid-1940s), theology. Background of The Fundamentals Series of twelve little volumes, each a collection of essays. Published between 1910 and 1915. Financed by Lyman (and Milton?) Stewart of Union Oil. Originally planned and edited by A. C. Dixon. When Dixon took Spurgeon’s Tabernacle, editorship shifted to Louis Meyer and then R. A. Torrey. Total of 90 essays and around 64 authors. Editors of The Fundamentals A. C. Dixon R. A. Torrey Content of The Fundamentals 29 articles dealing with the Bible. 31 articles defending other key doctrines of the gospel. 30 articles of testimony, attacking cults, dealing with science and religion, or promoting missions and evangelism. The Articles on the Bible 15 dealt directly with higher criticism or attacked higher critical understandings of particular passages. 7 were written in praise of the Bible. 2 discussed archeological confirmation of biblical accounts. What Was The Fundamentals? Obviously, an attempt to defend the core of biblical Christianity, beginning with the Bible itself. The writers were a miscellaneous collection of individuals employed ad hoc. They never met, did not all work together, and did not constitute a movement of any sort. More than anything, the series reflected the concerns of the original planner, A. C. Dixon. Definitely NOT the beginning of the fundamentalist movement. Laid some intellectual groundwork. What about Fundamentals? The notion is as old as the Regula Fidei. The Four Chief Symbols were attempts to articulate fundamentals. The Reformers and their followers wrote extensively about fundamental doctrines. The notion of fundamental doctrines (and practices) received renewed emphasis during the middle third of the 19th century, especially by the Old School Presbyterians. There was a widespread recognition of the necessity of both primary and secondary separation. Separation Primary separation is non-extension of Christian fellowship to those who deny the gospel (by denying a fundamental). Secondary separation of limitation of Christian fellowship at some level toward brethren who reject some nonfundamental aspect of the faith. Denominationalism is an example of secondary separation. So was the division between Old and New School Presbyterians. Nearly every Christian practices secondary separation somehow, but not everyone will admit it. So What Was New, 1870-1920? There was a new error, liberalism or modernism. This error arose within the mainline denominations. There was a question as to how serious the error was and how long it would persist. The original tendency was to minimize the error, believing that the liberals would outgrow it. By the time its gravity became evident, liberalism was already well entrenched. The question now became one of continuing to extend Christian fellowship to liberals.