File

advertisement

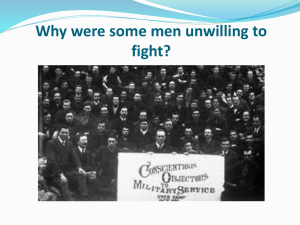

• http://www.keystagehistory.co.uk/freesamples/GCSE-history-source-work.html • Activities put together on the basis of some of the ideas above 1. What type of source is this? 2. Explain. 3. Date the source. 4. How can you tell? 5. What does it tell us? “A friend of mine phoned me and said “What are you doing about the war?” Well, I had thought nothing about it at all. He said, “Well, I have joined my brother's regiment which is the Honourable Artillery Company. If you like, come along, I can get you in.” At lunchtime I left the office, in Southampton Row, went along to Armoury House, in the City Road, and there was my friend waiting for me. There was a queue of about a thousand people trying to enlist at the time, all in the HAC - it went right down City Road. But my friend came along the queue and pulled me out of it and said, “Come along!” So I went right up to the front, where I was met by a sergeant-major at a desk. My friend introduced me to the sergeant, who said, “Are you willing to join?” I said, “Yes Sir.” He said, “Well, how old are you?” I said, “I am eighteen and one month.” He said, “Do you mean nineteen and one month?” So I thought a moment and said, “Yes Sir.” He said, “Right-ho, well sign here please.” He said, “You realise you can go overseas?” So that was my introduction to the Army.’” Reginald Haine, who joined the Honourable Artillery Company, recalls enlisting in the First World War. The extract comes from Forgotten Voices of the Great War. It was edited by Max Arthur for Ebury Press in association with the Imperial War Museum and published in 2002. “A friend of mine phoned me and said “What are you doing about the war?” Well, I had thought nothing about it at all. He said, “Well, I have joined my brother's regiment which is the Honourable Artillery Company. If you like, come along, I can get you in.” At lunchtime I left the office, in Southampton Row, went along to Armoury House, in the City Road, and there was my friend waiting for me. There was a queue of about a thousand people trying to enlist at the time, all in the HAC - it went right down City Road. But my friend came along the queue and pulled me out of it and said, “Come along!” So I went right up to the front, where I was met by a sergeant-major at a desk. My friend introduced me to the sergeant, who said, “Are you willing to join?” I said, “Yes Sir.” He said, “Well, how old are you?” I said, “I am eighteen and one month.” He said, “Do you mean nineteen and one month?” So I thought a moment and said, “Yes Sir.” He said, “Right-ho, well sign here please.” He said, “You realise you can go overseas?” So that was my introduction to the Army.’” What do you think is in the other half of this image? Who produced? When? Why? Poster commissioned by The British Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, and designed by Savile Lumley. It was published in 1915 Ripples of certainty: Discuss with a partner and write down anything you can work out from this image. The closer to the image you are the more certain you are. A poster published in 1940 by the royal air force in the second world war 1. Highlight any job roles/recruitment groups/political acts 2. How would you describe Albert Rowland? 3. How “typical” was Albert Rowland’s experience? 4. Give this source a caption. I was called up by the Military Training Act of May, 1939. This was replaced by the National Service Act in September, 1939. I refused to enlist. At that time, about 1940, I was deeply involved as a Christian in the peace movement. Several of us organised a public meeting in at the local Baptist Church. The meeting was packed. There were also a number of police officers stood at the back of the hall. From then on I and a friend were watched. Later, we were found with copies of the ‘Peace News’ and I was sentenced to five weeks’ imprisonment. After release, I was working for an engineering firm and was set to work on a machine for filling cartridges. I refused and was sacked. After a tribunal I was allowed to stay in my work. Other conscientious objectors weren’t so lucky: some were moved to agricultural work; others were given ‘noncombatant’ work in the services. The most insincere group of conscientious objectors were the ‘political objectors’, the left wing, who were lazy and had no consciences. When Russia entered the war on our side, some of them joined the armed forces. Albert Rowland recalls his time as a conscientious objector in the Second World War. From his contribution to the BBC’s People’s War website, provided in 2005. I was called up by the Military Training Act of May, 1939. This was replaced by the National Service Act in September, 1939. I refused to enlist. At that time, about 1940, I was deeply involved as a Christian in the peace movement. Several of us organised a public meeting in at the local Baptist Church. The meeting was packed. There were also a number of police officers stood at the back of the hall. From then on I and a friend were watched. Later, we were found with copies of the ‘Peace News’ and I was sentenced to five weeks’ imprisonment. After release, I was working for an engineering firm and was set to work on a machine for filling cartridges. I refused and was sacked. After a tribunal I was allowed to stay in my work. Other conscientious objectors weren’t so lucky: some were moved to agricultural work; others were given ‘noncombatant’ work in the services. The most insincere group of conscientious objectors were the ‘political objectors’, the left wing, who were lazy and had no consciences. When Russia entered the war on our side, some of them joined the armed forces.