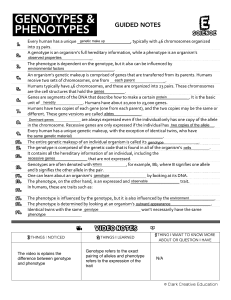

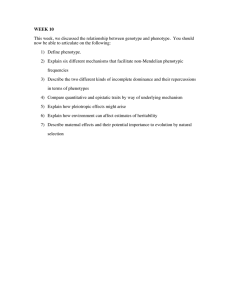

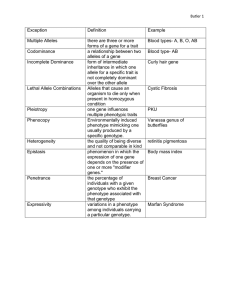

Genes and Evolution 2025 Lecture 1: 1. Evolution 2. Phenotypic Variation 3. Genetic Variation 4. Mutation The genome contains an organism's the complete set of instructions for development, survival and reproduction CATCATCATCAT The genome contains an organism's the complete set of instructions for development, survival and reproduction Genetic variation encodes the differences among organisms A single allele in IGF1 (insulin growth factor 1) determines small body size in dogs Sutter et al (2007) Science small CCGCAAGAGGGTCCTATGCT dogs CCGCAAGAGGGTCCTATGCT big CCGCAGGAGGGTCCTATGCT dogs CCGCAGGAGGGTCCTATGCT CATCATCATCAT Genetics enables us to quantify, test and measure the basis of evolution (and rule out incorrect hypotheses) To distinguish between alternative explanations: • Formulate expectations • Quantify genetic variation • Measure, calculate & test Species are not static, but change through time What processes underlie this change through time? Species are not static, but change through time What processes underlie this change through time? Two possibilities: 1. Transformational change (things morph through time, e.g. Lamarckism) Ancestral giraffes stretched their necks Their offspring inherited stretched necks Species are not static, but change through time What processes underlie this change through time? Two possibilities: 1. Transformational change (things morph through time, e.g. Lamarckism) Ancestral giraffes stretched their necks Their offspring inherited stretched necks 2. Variational change (descent with modification, e.g. Darwinism) Ancestral giraffes varied in neck length Long-necked giraffes survived and passed on genes to offspring Darwinian Evolution – i. species evolve via descent with modification over long evolutionary time scales f m F q p b o c XIV a14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 XIII XII XI f10 a10 a9 f9 k8 a8 a7 l7 k7 f6 a6 d5 a5 d4 a4 l8 m9 IX m8 VIII m7 VII m6 VI k5 m5 V m4 i3 s2 a1 X k6 i4 a3 a2 l7 m10 E10 F10 IV m3 III m2 II m1 A B I C D E F “... we have only to suppose the steps in the process of modification to be more numerous or greater in amount, to convert these three forms into well-defined species” Darwin, (1859) Origin of Species, 2nd Edition. p.120 G H ICharles K L Darwin a14 q14 p14 Darwinian Evolution – ii. natural selection favors beneficial traits generations f m F passed on to subsequent o c XIV 14 b14 14 14 14 14 XIII XII XI f10 a10 a9 f9 k8 a8 a7 l7 k7 f6 a6 d5 a5 d4 a4 l8 m9 IX m8 VIII m7 VII m6 VI k5 m5 V m4 i3 s2 a1 X k6 i4 a3 a2 l7 m10 E10 F10 IV m3 III m2 II m1 A B I C Alfred R Wallace D E F “... we have only to suppose the steps in the process of modification to be more numerous or greater in amount, to convert these three forms into well-defined species” Darwin, (1859) Origin of Species, 2nd Edition. p.120 G H ICharles K L Darwin “…this new, improved, …race might …give rise to new varieties, exhibiting several diverging modifications, any of which, tending to increase the facilities for preserving existence, must, by the same general law, in their turn become predominant. ” Wallace (1858) On the Tendency of Varieties to depart indefinitely from the Original Type. (2009). Alfred Russel Wallace Classic Writings. Paper 1. Evidence for “modification with descent” Herron & Freeman - chapter 2 (also discussed later in course) Evidence for “evolution by natural selection” (we discuss in detail this week) ‘typica’ – lower fitness at polluted sites ‘carbonaria’ – high fitness at polluted sites Biston betularia, Peppered moth. Wikimedia, CC. The mechanisms of evolutionary change The mere recognition of a pattern does not constitute a scientific study If we claim to understand the evolution of a trait or of the diversity of species, we must not only explain what happened but also the mechanisms responsible Studying the mechanisms of evolutionary change requires the inclusion of genetics and heredity Darwin didn’t know the mechanism of “descent with modification” At the time, “Blending inheritance" was assumed. (ie. characters of both parents were mixed in offspring) Spikiness & color mixed in offspring Darwin didn’t know the mechanism of “descent with modification” At the time, “Blending inheritance" was assumed. (ie. characters of both parents were mixed in offspring) But around the same time, Mendel was busy studying peas Gregor Mendel, 1822-1884 Spikiness & color mixed in offspring Mendel showed that traits (characters) are inherited independently of one another At the time, “Blending inheritance" was assumed. (ie. characters of both parents were mixed in offspring) But around the same time, Mendel was busy studying peas Gregor Mendel, 1822-1884 Mendel’s laws of inheritance: 1. Law of segregation (diploid alleles separate in gametes) Spikiness & color mixed in offspring 2. Law of independent assortment (alleles of different genes separate independently of one another) 3. Law of dominance (when two alleles at a locus are present, the dominant allele can mask the effects of the weaker allele) Mendel’s work laid the foundation for modern genetics Gregor Mendel, 1822-1884 He chose seven traits to study: They all happened to be controlled by single/few genes with alleles of large effect. (notable segregation of phenotypes in progeny) The genes all happened to be unlinked (on different chromosome) - clear patterns of trait independence in progeny But, others showed that many traits are continuous (not discrete), and influenced by the environment… How to reconcile evolutionary mechanism that fits both ”Mendelian” discrete traits with independent assortment and continuous traits with quantitative variation? The Evolutionary “Modern Synthesis” Action of numerous genetic and environmental factors gives continuous distribution in traits Natural selection can lead to changes in allelic frequencies Small populations subject to stochasticity “genetic drift” Species are reproductively isolated groups of organisms Key contributors: Ronald Fisher Sewall Wright JBS Haldane Theodosius Dobzhansky Ernst Mayr …and many others Theory of adaptive evolution by natural selection after the Modern Synthesis The reformulation of Darwin’s postulates: 1. Individuals vary as a result of mutations 2. Individuals pass on their alleles to their offspring 3. In every generation, some individuals are more successful at surviving and reproducing than others 4. The most successful individuals are (not a random subset of the population, but) those with alleles and allelic combinations that best adapt them to their environment The outcome is that alleles associated with higher fitness increase in frequency over generations ➔ adaptive evolution What is evolution? Genetic variation is the raw material for evolution It can be quantified and studied to identify evolutionary patterns and to test hypotheses on evolution and evolutionary processes Evolution is the changes in allele frequencies over time By natural selection: individuals carrying particular alleles do better Random and other processes may also lead to evolution We can use DNA to study evolution, and evolution to study how DNA functions The information we extract from DNA connects variation in individual genomes to: phenotypes population-level processes, and the generation of biodiversity It allows us to reach back in time and test hypotheses on individuals, traits, populations, species! In ecology and evolution DNA is used to: • identify species, families (paternity), populations, diets • track organisms through time & space • reconstruct evolution of adaptations, ancestors, phylogenies, species origins and extinctions, body plans In genetics and developmental biology evolution is used to: • identify functional parts of the genome • connect genotype to phenotype • dissect how molecular processes and pathways work. Mutations are essential for evolution, but not all mutations are good or bad Mutation creates differences (variants) among individuals Mutations can be lost or inherited by offspring DNA is copied and passed from generation to generation (including DNA variants) 50% of a parent’s genome is passed on to offspring Mutations are essential for evolution, but not all mutations are good or bad Mutation creates differences (variants) among individuals Mutations can be lost or inherited by offspring DNA is copied and passed from generation to generation (including DNA variants) 50% of a parent’s genome is passed on to offspring Mutations arise continuously, but most are somatic (not germline), and DNA repair mechanism are very good. Few are passed on to next generation through the germline (gametes) Mutations arise continually, but the genome is big and mutation rates are very low How many mutational differences between any two humans? 4-6M differences out of 3billion positions 0.01% Natural selection acts on individual variation, but evolutionary consequences occur in populations Individuals Populations Individuals differ (both in phenotype & genotype) Populations can differ (in phenotypic and genetic composition) Natural selection acts on the individual phenotype Populations are not the target of natural selection Individuals do not evolve Evolution can be observed at the level of populations. Any changes to their phenotype are NOT passed on to their offspring (It is a change in the frequency of an allele in the population over time) Changes in the frequencies of genetic variation over time = Evolution Frequencies may change: through natural selection when a DNA sequence variant is either beneficial or deleterious (differential survival, reproductive output) Through random processes, such as chance events (“drift”) due to migration non-random mating or mutation of a new allele Changes in the frequencies of genetic variation over time = Evolution Frequencies may change: A C G through natural selection when a DNA sequence variant is either beneficial or deleterious (differential survival, reproductive output) several generations 10s to >>10000s Through random processes, such as chance events (“drift”) due to migration non-random mating or mutation of a new allele Frequency of variant in geneX in an ancestral population Mutation New T allele arises Natural Selection favors C allele Drift random changes GA C A C G TC A G Not all evolution is adaptive or occurs by natural selection ! Evolution by natural selection is a non-random process Populations become better adapted to their environment Random and other processes may also lead to changes in allele frequencies ( = evolution) Mutation Chance events (genetic drift) Migration Non-random mating Different processes operate simultaneously, but they may differ in strength and importance A window back in time: by studying present day DNA variation, we can reconstruct the past (ancestral coalescence) Full geneology DNA is copied and passed from generation to generation (including DNA variants) Ancestry of extant lineages Ancestry of sampled lineages Coalescent tree of sampled lineages The shape of genealogy reflects population history Different evolutionary and demographic processes lead to different patterns of change in allele frequency Stable population Expanding population Shrinking population Evolution = change over time (generations) Five key processes influencing evolution Mutation Migration & Gene Flow Non-random mating Drift & Bottlenecks (small population size) Adaptation & Selection HWE (null model) Five Fingers of Evolution, Paul Anderson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5NdMnlt2keE Fundamental principles of evolutionary change Individuals differ from one another Today Genetic variation arises by random mutation and recombination Today The proportions of alleles and genotypes within a population change over time Tuesday Such changes in the proportions of genotypes may occur either by nonrandom, consistent differences among genotypes in survival or reproduction rates (natural selection) or by random fluctuations (genetic drift) Wednesday, Thursday, Friday As a result of different histories of genetic drift, gene flow and natural selection, populations of a species may diverge New taxa arise from prolonged, gradual evolution & all species form a great tree of life (phylogeny) The molecular basis of traits and adaptation affect their evolution (multiple loci, genomes) Week 2: Monday, Wednesday Week 2: Thursday & Friday Week2: Tuesday & Week 3: Monday Pause ii. Phenotypic Variation Both genes and the environment influence an organisms’ phenotype Phenotype - an observable characteristic of an organism may be external (e.g. morphology, behaviour) or internal (e.g. physiology) Phenotypic Variation Both genes and the environment influence an organisms’ phenotype Phenotype - an observable characteristic of an organism may be external (e.g. morphology, behaviour) or internal (e.g. physiology) P ~ G Phenotype ~ genotype (trait) (allelic variant) + + E environment + + (conditions during life) (G x E) gene x environment (interactions) What does this formula mean? P ~ G Phenotype ~ genotype (trait) + + An individuals Genotype + environment (allelic variant) Variation in phenotype E 12.0 6.0 16.5 1.8 GG GC GG CC + gene x environment (conditions during life) + the environment an individual has experienced “is dependent on, can be predicted by, or can be explained by” Ind1 Ind2 Ind3 Ind4 (G x E) 10℃ 10℃ 25℃ 25℃ (interactions) + an interaction term that modifies the environmental effect in some genotypes Bigger Smaller Bigger Smaller What does this formula mean? phenotypic variation explained heritable by variation P ~ G Phenotype ~ genotype (trait) (allelic variant) + + not heritable variation + heritable variation + E + (G x E) environment + (conditions during life) gene x environment (interactions) P ~ G Phenotype ~ genotype (trait) Variation in phenotype Ind1 Ind2 Ind3 Ind4 12.0 6.0 16.5 1.8 (allelic variant) An individuals Genotype GG 2 GC 1 GG 2 CC 0 Phenotypic score The genetic basis of a phenotype is often modelled using a simple regression eg Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) Recode the genotype as number of G alleles 0,1 or 2 A linear regression P ~ β0 + β1*genotype + ε 0 1 2 CC GC GG How many copies of G allele? P ~ G Phenotype ~ genotype (trait) Variation in phenotype Ind1 Ind2 Ind3 Ind4 12.0 6.0 16.5 1.8 (allelic variant) An individuals genotype GG GC GG CC Phenotypic score But there are some assumptions to keep in mind (e.g. additivity) A linear regression assumes the allelic effect is additive (phenotype of GC heterozygotes is midway A linear regression between phenotype of CC & GG homozygotes) P ~ β0 + β1*genotype + ε 0 1 2 CC GC GG How many copies of G allele? ~ G Phenotype ~ genotype (trait) (allelic variant) Phenotypic score P G allele is dominant over C The mode of inheritance may not be additive. A heterozygote may resemble one of the homozygote classes (ie. the allele may be dominant or recessive) 0 1 2 CC GC GG How many copies of G allele? P ~ G Phenotype ~ genotype (trait) (allelic variant) Phenotypic score The mode of inheritance may not be additive. A heterozygote may resemble one of the homozygote classes (ie. the allele may be dominant or recessive) G allele is recessive to C 0 1 2 CC GC GG How many copies of G allele? How much of trait variation has a genetic component? (using parent-offspring regression to estimate heritability) Offspring trait value Heritability (h2): the amount of the variation in a trait that can be attributed to genetic variation Parents’ trait mean How much of trait variation has a genetic component? (using parent-offspring regression to estimate heritability) Offspring trait value Heritability (h2): the amount of the variation in a trait that can be attributed to genetic variation h2=0.90 (again only considers additivity of alleles). We refer to this as the “narrow-sense Heritability”. “Broad-sense heritability” refers to trait variance explained by all of these: additivity + dominance + epistasis Parents’ trait mean G: An individuals’ phenotype may be controlled by few or many genes that vary within a species (polymorphisms) Red / green color blindness (protonopia / deuteronopia) OPN1LW/OPN1MW genes Height many loci across the genome, each of small effect size Coloration in Geese single locus, two allelic variants Sexual dimorphism in wing pattern mimicry in butterflies few loci of large effect size A small experiment: measuring phenotypic variation in Genes & Evolution students! Can you taste Phenylthiocarbamide (PTC?) A. Yes, awful! B. Yes, somewhat C. Yes, tastes good D. No, I don’t taste anything (just soggy paper) What is Phenylthiocarbamide (PTC)? A synthetic chemical used specifically to study variation in human taste Phenylthiocarbamide The ability to taste PTC depends on the alleles you carry at the TAS2R38 taste receptor gene (chromosome 7). Genotypes at TAS2R38 explain 75% variation in PTC sensitivity There are two frequent haplotypes (alleles), and 3 rare ones “classical” taster allele (PAV) and non-taster allele (AVI) carry DNA mutations in 3 codons causing differences inTAS2R38 protein structure. TAS2R38: A gene encoding a bitter taste receptor Humans populations have genetic variation in the ability to taste PTC • Polymorphism is (mostly) due to variation at a single locus Woodings 2006 Genetics Can you taste Phenylthiocarbamide (PTC?) Phenotypic Variation Both genes and the environment influence an organisms’ phenotype not heritable phenotypic variation phenotypic variation P ~ G Phenotype ~ genotype (trait) heritable variation explained heritable by variation (allelic variant) + + E environment + + (conditions during life) (G x E) gene x environment (interactions) E: Environment may also influence an individual’s phenotype (”Phenotypic plasticity”: the ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes under different environmental conditions Sunburn in humans (extent of sunburn depends on amount of sun exposure) Calluses and blisters (extent of callus/blister depends on degree of mechanical stress) E: Environment may also influence an individual’s phenotype (”Phenotypic plasticity”: the ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes under different environmental conditions Wingless vs winged aphids in response to crowding on host plant (same genotypes grow wings when crowded) Helmets vs no-helmets in daphnia (water fleas) in response predator cues (same genotypes, grow helmets in presence of predators Phenotypic Variation Both genes and the environment influence an organisms’ phenotype phenotypic variation P ~ G Phenotype ~ genotype (trait) (allelic variant) heritable variation not heritable variation explained heritable by variation + + E environment + + (conditions during life) (G x E) gene x environment (interactions) G x E: Gene by environment interactions The effect of genotype on an organism’s phenotype depends on the environment (or equivalently, the effect of the environment on an organisms phenotype depends on the genotype) Mean number of bristles This is common! One classic example: Reaction norm: the pattern of phenotypic plasticity exhibited by a genotype Temperature Genes + Env (no interaction) G1 G2 E1 E1 E2 E2 G1=Genotype 1; G2=genotype 2; E1=Environment1; E2=Environment2 G1 Phenotype / Trait G1 G2 Genes only Phenotype / Trait Environment only Phenotype / Trait “main effects” (no interactions here) G x E Reaction Norms can have many different shapes G2 E1 E2 Genes + Env (no interaction) G1 G2 E1 E1 E2 E2 G1=Genotype 1; G2=genotype 2; E1=Environment1; E2=Environment2 G1 G2 E1 E2 Phenotype / Trait Genes x Env E1 E2 Genes x Env G1 G2 E1 G2 E2 Phenotype / Trait Genes x Env G1 Phenotype / Trait Phenotype / Trait G1 G2 Genes only Phenotype / Trait Environment only Phenotype / Trait GxE interactions (reaction norms) “main effects” (no interactions here) G x E Reaction Norms can have many different shapes G1 G2 E1 E2 Plasticity variation with a genetic basis (ie G x E) can evolve! Phenotypic plasticity can be adaptive - Use cues to estimate (future) environmental condition - React or anticipate: adjust phenotype accordingly to increase fitness Plasticity variation with a genetic basis (ie G x E) can evolve! Phenotypic plasticity can be adaptive - Use cues to estimate (future) environmental condition - React or anticipate: adjust phenotype accordingly to increase fitness When do you expect the degree of plasticity to become target of selection (i.e. a change in the reaction norm)? When cues and/or environmental conditions and/or optimal phenotype change, e.g. egg-laying date under changing climate What role does plasticity play in evolution? Two competing schools of thought: What role does plasticity play in evolution? Two competing schools of thought: 1. Plasticity “buffers” or “constrains” adaptive evolution (it dampens response to selection by obscuring the beneficial heritable genotype) ‘Plasticity “hides” the true phenotypic “read-out” of a genotype’ Phenotype / Trait (Blue-ness) Genes x Env G1 (bb) G2 (BB) E1 E2 What role does plasticity play in evolution? Two competing schools of thought: 1. Plasticity “buffers” or “constrains” adaptive evolution (it dampens response to selection by obscuring the beneficial heritable genotype) ‘Plasticity “hides” the true phenotypic “read-out” of a genotype’ 2. Plasticity facilitates adaptive evolution (when the environment changes, one part ot the plastic response may be favored enabling the population to persist and further variation be selected). Phenotype / Trait (Blue-ness) Genes x Env G1 (bb) G2 (BB) E1 E2 Only some parts of plasticity’s role in evolution are controversial In theory selection may favor any trait, when the variation in that trait has a heritable genetic basis Some evidence from Dutch birds… But rates of adaptation / selection may still be constrained / inefficient Science, 2005 Pause Part 3 iii. Genetic Variation Genetic Variation! How much genetic variation is there? among individuals? among populations? among species? How much genetic variation in natural populations? What type? How is it maintained? Three schools of thought in population genetics: Classical Populations are uniform Only one optimal wildtype genotype Natural selection is mostly “purifying” (removes / purges rare deleterious mutations) Fisher, Muller How much genetic variation in natural populations? What type? How is it maintained? Three schools of thought in population genetics: Classical Balancing (selectionist) Populations are uniform Polymorhpisms are common Only one optimal wildtype genotype Balancing selection maintains heterozygosity Natural selection is mostly “purifying” (removes / purges rare deleterious mutations) Selection is more important then drift in determining allele frequencies in a population Fisher, Muller Dobzhansky How much genetic variation in natural populations? What type? How is it maintained? Three schools of thought in population genetics: Classical Balancing (selectionist) Neutral Populations are uniform Polymorhpisms are common Most alleles are neutral in fitness effects Only one optimal wildtype genotype Balancing selection maintains heterozygosity Polymorphisms maintained by mutation + drift Natural selection is mostly “purifying” (removes / purges rare deleterious mutations) Selection is more important then drift in determining allele frequencies in a population Drift is more important than selection in determining allele frequencies Fisher, Muller Dobzhansky Kimura, Lewontin How much genetic variation in natural populations? What type? How is it maintained? Three schools of thought in population genetics: Classical Balancing (selectionist) “Nearly” Neutral Populations are uniform Polymorhpisms are common Too few polymorphisms! Most alleles are “nearly” neutral or slightly deleterious in fitness effects Only one optimal wildtype genotype Balancing selection maintains heterozygosity Polymorphisms maintained by mutation + drift + weak purifying selection removing slightly deleterious mutations Natural selection is mostly “purifying” (removes / purges rare deleterious mutations) Selection is more important than drift in determining allele frequencies in a population Drift is important but purifying selection may matter, especially in large populations. Fisher, Muller Dobzhansky Kimura, Lewontin, Ohta Experiments suggest that on average mutations are slightly deleterious… Evolve a virus over many generations, let it accumulate new mutations. Compare the effect of new mutations on fitness relative to ancestral strain fitness Many neutral Quite a few lethal! A number deleterious Few mutations are beneficial Fitness relative to ancestor But mutations also lead to adaptation (the rare beneficial mutations spread through the population) Fitness at the end of the experiment is higher than the original ancestor How do we measure and quantify genetic variation? P = percentage polymorphic sites/loci/genes # Does not tell us the number of alleles or their frequencies (might be very rare or very common) Population/Species 2 Population/Species 1 H = percentage of sites that are heterozygous # Gives an indication of mutation frequency and abundance across genome in an individual Ind1 ACTGGTCTCTCTTTCTGGGACGTGCTGAACATAGAACATGGAACTTTATATATATATAGACTTGTCAAT ACTGGTCTCTCT--CTGGGACGTGGTGAACATAGAACATGGAACTTTATATATATA--GACTTGTCAAT ACTGGTCTCTCTTTCTGGGACGTGCTGAACATAGATCATGGAACTTTATATA------GACTTGTCAAT Ind2 ACTGGTCTCTCTTTCTGGGACGTGCTGAACATAGAACATGGAACTTTATATATA----GACTTGCCAAT P = 5/70 H = 0.6 Ind2 ACTGGTCTCTCTTTCTGGGACGTGCTGAACATAGATCATGGAACTTTATATATATATAGACTTGCCAAT ACTGGTCTCTCTTTCTGGGACGTGGTGAACATAGAACATGGAACTTTATATA------GACTTGCCAAT ACTGGTCTCTCTTTCTGGGACGTGCTGAACATAGATCATGGAACTTTATATATATATAGACTTGCCAAT Ind3 ACTGGTCTCTCT--CTGGGACGTGCTGAACATAGATCATGGAACTTTATATATATATAGACTTGCCAAT ACTGGTCTCTCTTTCTGGGACGTGCTGAACATAGATCATGGAACTTTATATATATATAGACTTGCCAAT Ind4 ACTGGTCTCTCTTTCTGGGACGTGCTGAACATAGATCATGGAACTTTATATATATATAGACTTGTCAAT ACTGGTCTCTCTTTCTGGGACGTGCTGAACATAGATCATGGAACTTTATATATATATAGACTTGCCAAT Ind5 ACTGGTCTCTCTTTCTGGGACGTGCTGAACATAGATCATGGAACTTTATATATATATAGACTTGCCAAT P = 2/70 H = 0.13 Genetic variation in typical natural populations Estimates from allozyme electrophoresis for typical natural populations: P : 0.33 – 0.50 H : 0.04 – 0.15 Q: Why would more plant species have a very low heterozygosity ? Allozyme Heterozygosity Figure 5.25 Variant sites per genome (millions) Genetic variation in human populations decreases with distance from Africa Cheetahs have exceptionally low levels of genetic diversity Acinonyx jubatus raineyi : P = 0.04; H = 0.01 Acinonyx jubatus jubatus : P = 0.02; H = 0.0004 Populations derive from a very small number of founders (bottleneck) The amount of genetic variation in a species differs πS = synonymous nucleotide diversity (amount of ”neutral” differences between pair of chromosomes sampled) Romiguier et al Nature (2014) The amount of genetic variation in a species differs πS = synonymous nucleotide diversity (amount of ”neutral” differences between pair of chromosomes sampled) Life history strategies influencing population size are best predictors of genetic variation. Drift is a major force determining genetic diversity (more on Thursday!) Romiguier et al Nature (2014) Neutralist – selectionist controversy How much of genetic variation within a population is adaptive? The dispute is not on whether some mutations are neutral and others may be under balancing selection It is about the relative importance of one type over the other type of selection The substantial levels of protein variation shows us that much genetic variation exists in natural populations The remaining and unanswered question is how much of the genetic variation that exists in natural populations is adaptive Big open question with rapidly changing environment! Pause iv. Mutation: What is heritable genetic variation? iv. Mutation: What is heritable genetic variation? For majority of cases, genetic material is transmitted across generations in the form of DNA inside gametes Heritable genetic variation = differences in the nucleotide sequence of DNA that are passed on to subsequent generations ATAGATCATGG ATAGACCATGG Allele 1 Allele 2 Variation at the DNA sequence level can have functional effects that influence cell fate / function DNA transcription RNA translation Protein Concepts of Genetics, Figure 1.7 Genetic variation can occur anywhere in the genome (mutations are random without regard to whether they’ll be harmful or beneficial) But they may be distributed non-randomly across the genome due to mutation mechanism (e.g. crossing over occurs non-randomly) or due to selection (e.g. purifying selection removes individuals with deleterious mutations so less genetic variation in gene rich regions) Coding Stop ‘On’ in limb ‘Off’ in brain Coding 5’ Untranslated region Start 3’ UTR Protein Coding Exons Splice variant Differences at a given location in the genome are called “alleles” Homologous chromosomes ATAGATCATGG ATAGACCATGG the “T” allele the “C” allele Differences at multiple linked alleles are referred to as “haplotypes” Homologous chromosomes ATAGATCATGG ATAGACCATGG Haplotype 1 Haplotype 2 The term “genotype” is used to refer to the two alleles carried by an individual at a single locus: e.g. “T/C heterozygote or CC homozygote” But it can also be used more broadly, refer to haplotypes or entire genome. e.g. a genetic strain The type of difference at a given location depends on the type of mutation Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, “SNPs” ATAGATCATGG ATAGACCATGG Copy Number Variation ATAGAATAGAA ATAGACCATGG (CNVs, duplications) Insertions/deletions, “indels” ATAGA---TGG ATAGACCATGG Short Tandem Repeats e.g. “mini/microsatellites” Short Tandem Repeats 5-mer AGAGAGAGAGA e.g. “mini/microsatellites” 3-mer AGAGAG—---A 2-copy 1-copy ATAACTAGTGG ATAGATCATGG Different types of mutations are generated by different types of mechanisms (with different likelihoods/probabilities/frequencies) Mutagens e.g UV, chemical exposure DNA double-stranded break Copying errors during cell division / DNA repair Replication slippage Meiotic errors (unequal crossing over) Chromosomal aneuploidies Transposable elements (jumping genes) Meiosis: independent assortment Recombination! Crossing over creatings novel haplotypes … Mutations are random – the likelihood of a mutation occuring does not depend on whether it has a beneficial effect Overall, mutations rates are low (e.g. 10-8) and vary across taxa We are all mutants! Each human embryo has ~100 new mutations of which ~2 are deleterious Different mutation rates of different mutation types makes them useful for studying “recent” or “old” evolutionary change Category Approx Rate / Locus or bp SNP (base substitution) ~10⁻⁸ per base / generation Microsatellite (fast motif, many repeats) ~10⁻⁴ to 10⁻² per locus / generation Coding exons (under constraint) ~ lower than genomic average (e.g. fewer tolerated mutations) Intergenic / nonfunctional / nonconstrained regions ~= or higher than baseline per base, depending on mutational “hotspots” Mutations rates can differ across environments “Effect size” of mutations on phenotypes or fitness can range from none to drastic 1bp substitution can give resistance to pesticides Master control genes in development Fine tuning regulatory changes to transcription Pleiotropy: a single mutation may affect more than one character trait Meiosis and sexual reproduction are important sources of multilocus genetic variation: ATAGATGCATCAGGGTGG homolog 1 crossing over X ATAGATGCACCAGGGTGG homolog 2 ATAGATGCATCAGGGTGG ATAGATGCATCAGGGTGG ATAGATGCATCAGGGTGG parent1 ATAGATGCACCAGGGTGG gametes fertilization ATAGATGCACCAGGGTGG diploid offspring ATAGATGCATCAGGGTGG with novel haplotypes Take home summary of part iv. mutations Mutation = alterations in DNA that are subsequently replicated Different types” From point mutations / SNPs to alterations of segments of chromosomes to structural re-arrangments Type and location of mutation matters for its effect Mutation rate low, but not insignificant Necessary, but not sufficient, for evolution Changes in phenotype: from none to drastic Alters pre-existing biochemical or developmental pathways Mutations are random not directed: The likelihood that a mutation will occur does not depend on whether or not it would be advantageous. 90 Take home summary of part i. evolution Evolution occurs via variational change (descent with modification). Modern synthesis reconciles different fields of study of genetics, discrete, and continuous traits building a quantifiable and testable framework to describe evolution in natural populations as as a change in allele frequencies over time. Evolution requires heritable variation passed on to subsequent generations. Evolution is affected by a number of different forces: drift, non-random mating, mutation, migration, natural selection. By studying changes in allele frequencies over time, we can quantify the effects of these forces. Natural selection acts on individual variation, but evolutionary consequences occur in populations DNA can be used to reconstruct historical relationships (ancestry) using coalescence Shapes of genealogies can be use to infer changes in demographic history 91 Take home summary of part ii. phenotypic variation Phenotypic variation may be caused by genes, environment, gene x environment interactions (or a combination of all three). The genetic basis of a trait is commonly tested using linear models (regression) Alternatively the amount of variation in a trait that can be explained by genes, heritability h2, can be estimated from parent/offspring regression. Additivity is a typical assumption, yet alleles can also act in a recessive/dominant fashion. Plasticity described changes in phenotype in response to changes in the environment by a single genotype. The lack of a heritable component to pure plasticity, makes its role in evolution questionable. But the strength/nature/extent of plasticity may vary among individuals and can have a genetic basis -> gene x environment interactions. Evidence of plasticity being heritable and responding to selection But its role in constraining/buffering vs facilitating rates of adaptive evolution is still debated. 92 Take home summary of part iii. genetic variation Genetic variation in a population can be measured by: proportion of variable sites, or percentage heterozygous sites (and diversity) nucleotide The amount of genetic variation varies across species, and can be affected by processes such as population bottlenecks and drift. Variation in genetic variation across diverse taxa is predicted by population size so drift may be an important force maintaining variation. Most mutations appear neutral or slightly deleterious Yet mutations can also be adaptive. There is still some debate about the forces maintaining genetic diversity. Why is it not all lost/purged from the population? “classical school”, vs “balancing selection” school vs. neutral/nearly neutral school. 93 Some key terms you’ve heard today (they’ll appear more throughout the course) Variation change, descent with modification, natural selection Mendelian genetics: segregation, independent assortment, dominance/additivity Discrete vs continuous traits The ”modern synthesis” of evolution Different types of selection: Natural selection, purifying selection, balancing selection Drift Phenotypic variation. P ~ G + E + GxE Heritability Gene x environment effects, reaction norms Phenotypic plasticity: plasticity constrains or facilitates rapid adaptation? Heritable genetic variation Allele, Genotype, Haplotype, chromosome homologs Heterozygous, Homozygous Recessive, additive, dominant alleles Gene, locus, non-coding, intergenic, regulatory Mutations types: e.g single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), microsatellite repeat number Mutation effect size and direction: strong/weak, beneficial/neutral/deleterious Percentage of polymorphic sites, percentage of heterozygous sites, nucleotide diversity Pleiotropy Tomorrows topic: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium The use of population genetics to study evolution Determine allele and genotype frequencies to detect the presence and the mechanisms of evolutionary change Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE): frequencies of alleles and genotypes remain unchanged from generation to generation Frequencies do not change on their own Deviations from HWE can provide indication for evolutionary processes Herron & Freeman (Chapter 6): Mendelian genetics in populations (pages 193 - 205) Crucial concepts & definitions you need to know for tomorrow! Phenotype Genotype, Homozygous, Heterozygous Gene locus Alleles Chromosome homologues Homozygous / heterozygous Dominant / recessive 96 Further information for those interested… Mendel’s three laws of inheritance Gregor Mendel, 1822-1884 i. Law of segregation (diploid alleles separate in gametes) Gregor Mendel, 1822-1884 A Aa Mendel’s laws of inheritance: 1. Law of segregation (diploid alleles separate in gametes) a 1n 2n organism gametes II. Law of independent assortment (alleles of unlinked genes separate independently) Gregor Mendel, 1822-1884 B b Mendel’s laws of inheritance: 1. Law of segregation (diploid alleles separate in gametes) Bb B 2. Law of independent assortment (alleles of different genes separate independently of one another) b 2n organism 1n gametes III. Law of dominance when two alleles, a dominant allele can mask recessive allele Gregor Mendel, 1822-1884 Mendel’s laws of inheritance: 1. Law of segregation (diploid alleles separate in gametes) 2. Law of independent assortment (alleles of different genes separate independently of one another) 3. Law of dominance (when two alleles at a locus are present, the dominant allele can mask the effects of the weaker allele) Tall allele is dominant over recessive dwarf alllele What role might plasticity play in evolution? Two competing schools of thought: 1. Plasticity “buffers” or “constrains” adaptive evolution (it dampens response to selection by obscuring the beneficial heritable genotype) ‘Plasticity “hides” the true phenotypic “read-out” of a genotype’ Example reasoning: 1. Blue individuals are fittest. Selection favors ”blueness”. Phenotype / Trait (Blue-ness) Genes x Env 2. GxE interaction: G2 (BB homozygote) is blue in all conditions G1 (bb) G1 (bb homozygote) is plastic: red in E1 and blue in E2 G2 (BB) Blue genotype (G2) is fittest. 3. Selection acts at the phenotypic level, and can only distinguish between G2 and G1 in some circumstances (E1). In E2 they look phenotypically the same. E1 E2 4. The rate at which the populations is fixed for the beneficial B allele is slowed down, because bb alleles persist in some circumstances. Selection is inefficient. What role might plasticity play in evolution? Two competing schools of thought: 1. Plasticity “buffers” or “constrains” adaptive evolution (it dampens response to selection by obscuring the beneficial heritable genotype) ‘Plasticity “hides” the true phenotypic “read-out” of a genotype’ 2. Plasticity facilitates adaptive evolution (when the environment changes, one part ot the plastic response may be favored). Example reasoning: Phenotype / Trait (Blue-ness) Genes x Env E1 1. The selection pressure changes and favors the red phenotype. G1 (bb) 2. Plasticity of G1 (bb) individuals means they are fitter in E1 than G2 (BB). G2 (BB) 3. The population can persist in E1. E2 4. New or existing genetic variation is “exposed” to new selection presure, they stabilize / reinforce the trait. 5. Selection can now favor red phenotypes that are produced even without environmental trigger (plasticity). Ie. It becomes fixed or “assimilated” Sexual reproduction is an important source of multilocus genetic variation: Recombination - existing variation ”reshuffled” by meiosis ATAGATGCATCAGGGTGG homolog 1 crossing over X ATAGATGCACCAGGGTGG homolog 2 ATAGATGCATCAGGGTGG ATAGATGCATCAGGGTGG ATAGATGCATCAGGGTGG parent1 ATAGATGCACCAGGGTGG gametes fertilization ATAGATGCACCAGGGTGG diploid offspring ATAGATGCATCAGGGTGG with novel haplotypes Three sources of genetic variation from sexual reproduction: 1. Independent assortment of chromosomes during meiosis e.g. humans: max 223 possible chromosome combinations from one parent. 2. During meiosis, homologous chromosomes align, and at least 1 cross-over occurs. Alleles previously on opposite chromosome homologs can become linked Alleles linked on the same chromosome homolog can be unlinked e.g. humans: >> 423 possible chromosome combinations from one parent. 3. During fertilization, the union of gametes brings together different combinations of alleles from meiosis in both parents.