Introduction

Wind is a significant force that must be considered in the design of structures. ASCE 7-16 provides a

comprehensive methodology for calculating wind loads on buildings and other structures. This lecture will

cover the key provisions of ASCE 7-16 for wind load calculation.

1. Importance of Wind Load Calculations

Wind can exert significant forces on structures, affecting both their overall stability and the integrity of

individual elements. Incorrect wind load calculations can lead to structural failure, discomfort to occupants, or

even catastrophic collapse. ASCE 7-16 provides the necessary framework to accurately compute wind loads.

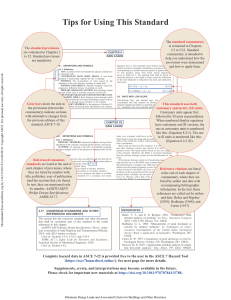

Permitted Procedures (ASCE 7-16) Section 26.1.2

outlines the permitted methods for determining wind loads on buildings and structures. The wind load

calculation process is separated into two main categories:

1. Main Wind Force Resisting System (MWFRS): This refers to the primary structural system responsible

for transferring wind loads from the building to the ground. MWFRS includes systems like frames, walls,

and roofs that resist overall building loads.

2. Components and Cladding (C&C): These refer to smaller elements of a structure, such as windows,

doors, and roof panels, that are directly exposed to wind pressures. These elements do not contribute

to the overall stability of the structure but are vulnerable to wind loads.

Main Wind Force Resisting System (MWFRS):

The Main Wind Force Resisting System (MWFRS) is the structural system that is responsible for transferring

wind forces acting on the building's exterior surfaces to the foundation. These forces arise from wind pressure

acting on walls, roofs, and other surfaces, and the MWFRS distributes them safely into the ground.

According to Section 26.1.2.1 of ASCE 7-16, wind loads for the MWFRS must be determined using one of the

following four procedures. These methods account for the building’s height, shape, and complexity, ensuring

that the structure can safely resist wind forces. Here’s a breakdown of each procedure:

1. Directional

Procedure

(Chapters

27):

The Directional Procedure applies to buildings of all heights, provided they meet specific criteria laid

out in Chapter 27. This method takes into account wind direction and calculates wind pressures acting

on the building based on its exposure, geometry, and height.

•

Application: The Directional Procedure is applicable for buildings of all heights.

•

When to Use: This procedure is used for most standard buildings that meet the specific requirements

provided in Chapter 27.

•

How it Works: The Directional Procedure calculates wind loads based on wind acting from a particular

direction, considering variables such as wind speed, exposure, height, and the structural configuration

of the building. It provides detailed pressure coefficients for the various faces and roof slopes of the

building.

Example: This method is commonly used for high-rise buildings or complex structures where wind direction

and exposure significantly impact the load distribution. For example, a skyscraper in an urban setting would be

analyzed using this procedure to assess wind pressures from different angles.

2. Envelope

Procedure

(Chapter

28):

The Envelope Procedure is specifically for low-rise buildings that meet the requirements in Chapter

28. Low-rise buildings are typically defined as those with a height less than or equal to 60 feet. This

procedure simplifies wind load calculations by using predefined pressure coefficients, thus avoiding

the need for complex directionality analysis.

•

Application: The Envelope Procedure is applicable to low-rise buildings (typically less than or equal to

60 feet in height).

•

When to Use: This procedure is used for buildings that meet the specific criteria outlined in Chapter 28,

such as simple, regular-shaped buildings with low rise.

•

How it Works: The Envelope Procedure simplifies the calculation of wind loads by using predefined

pressure coefficients and does not require analysis for different wind directions. This procedure

considers both positive and negative pressures that may act on the building envelope as a whole.

Example: This method is ideal for small office buildings, warehouses, or residential homes, where wind

exposure is more uniform, and building geometry is relatively simple.

3. Simplified

Procedure

(Chapter

27,

Part

2):

This is used for low-rise buildings (heights less than or equal to 60 feet) in less complex settings. The

Simplified Procedure provides a more straightforward method for calculating wind loads using basic

wind speed and building dimensions, suitable for structures with simpler configurations.

4. Directional Procedure for Building Appurtenances and Other Structures (Chapter 29)

This specialized Directional Procedure addresses building appurtenances (rooftop structures like HVAC

systems) and other structures, including:

•

Rooftop equipment (e.g., air conditioning units)

•

Freestanding walls and signs

•

Chimneys, tanks, open signs, single-plane open frames, and trussed towers

Since these elements are often more exposed and prone to higher wind forces due to their location or

shape, this procedure considers their unique structural challenges.

•

When to Use: This procedure is used when designing wind loads for these non-building elements,

ensuring that they can withstand wind forces.

•

How it Works: Similar to the directional procedure for buildings, this method calculates wind loads

based on directional wind pressures but specifically adapts it to appurtenances and special structures.

Example: For a large shopping mall with signage on the rooftop or external freestanding signs, this method

helps calculate the wind loads on these features, ensuring they are properly anchored to resist high winds.

5. Wind

Tunnel

Procedure

(Chapter

31):

The Wind Tunnel Procedure is the most detailed and precise method, used for both buildings and

other structures of all types. It is required when the other methods are insufficient due to the

complexity of the structure, such as buildings with unusual shapes or located in areas with significant

wind variability.

•

Application: The Wind Tunnel Procedure can be used for all buildings and other structures.

•

When to Use: This procedure is typically employed for buildings with unusual shapes, complex

geometries, or large structures that require more precise wind load analysis. It is also used for buildings

where wind loads cannot be accurately determined using the simpler methods, such as tall

skyscrapers or unique architectural forms.

•

How it Works: This method involves physical wind tunnel testing or advanced computational fluid

dynamics (CFD) simulations. The procedure captures the effects of wind acting on the structure in realworld conditions, providing highly accurate wind load data.

Example: When designing an irregularly shaped museum or sports stadium, wind tunnel testing may be

necessary. Engineers conduct physical or computational tests in a controlled environment to accurately

simulate wind behavior and determine wind loads.

Conclusion

These procedures ensure that the MWFRS of a building or structure is designed to safely transfer wind loads to

the ground. By selecting the appropriate method—whether it's the Directional Procedure for tall buildings, the

Envelope Procedure for low-rise structures, or the Wind Tunnel Procedure for more complex designs—

engineers can ensure both the safety and functionality of the building in varying wind conditions.

Overall Process Overview (Fig. 26.1-1)

•

Step 1: Choose the appropriate design procedure based on the structure’s height, geometry, and

complexity.

•

Step 2: Determine the Basic Wind Speed (V) for the location using wind speed maps provided in the

standard.

•

Step 3: Identify the Risk Category of the building (I, II, III, or IV) to adjust for safety factors.

•

Step 4: Select the Exposure Category (B, C, or D) based on the surrounding terrain.

•

Step 5: Use the selected procedure (Directional, Envelope, Simplified, or Wind Tunnel) to calculate the

wind pressures acting on the MWFRS and C&C elements.

These procedures ensure that the wind loads are appropriately calculated, taking into account the building's

location, exposure, height, and risk category.

In summary, Section 26.1.2 gives engineers flexibility in selecting the most suitable method for wind load

determination while ensuring compliance with ASCE 7-16 standards for different building types and scenarios.

BASIC WIND SPEED, V:

The Basic Wind Speed (V) is defined in ASCE 7-16 as the 3-second gust speed measured at 33 feet (10

meters) above the ground in Exposure C conditions. This wind speed is determined using historical wind data

and is used as a starting point for calculating design wind loads on structures.

Key Aspects:

1. 3-second gust speed: This represents the peak wind speed averaged over a 3-second interval, which is

considered short enough to capture the most intense gusts that a structure may experience during

extreme wind events (such as hurricanes, storms, or tornadoes).

2. 33 feet (10 meters) above ground: The wind speed is measured at this height, which is standard for

open terrain conditions. This height is chosen because it provides a uniform reference point for wind

speed measurements.

3. Exposure C (Section 26.7.3): Exposure C represents open terrain with scattered obstructions (like

flat fields or sparsely populated rural areas). Wind speeds in Exposure C are higher compared to

sheltered or urban areas (Exposure B), as there are fewer obstructions to slow down the wind.

4. Determination (Section 26.5.1): The basic wind speed is determined from wind speed maps provided

in ASCE 7-16 (Figures 26.5-1A to 1D), which show the geographic distribution of wind speeds across

different regions of the United States. The wind speeds correspond to certain probabilities of

occurrence, depending on the structure's risk category and location.

Application:

Once the Basic Wind Speed (V) is determined from the maps, it is used as part of the formula to calculate the

wind pressure acting on a structure. Adjustments are made based on factors like building height, exposure

category, and importance factor, but the basic wind speed serves as the foundation for all subsequent

calculations related to wind loads.

This helps ensure that structures are designed to resist wind forces based on the most severe wind events

expected in the building's location.

What is 3sec Gust speed?

The 3-second gust speed refers to the maximum wind speed averaged over a period of 3 seconds. This value is

used to represent the most extreme wind conditions that a structure might experience during a storm,

hurricane, or other high-wind events. It is measured at a height of 33 feet (10 meters) above ground level in

open terrain (Exposure C conditions).

The mean of a 3-second gust speed can be calculated by summing the wind speeds measured at each second

interval within the 3-second window and dividing by 3. For example, if the wind speeds measured at each

second were 10 m/s, 12 m/s, and 15 m/s, then the mean of the 3-second gust speed would be (10 + 12 + 15) / 3

= 12.3 m/s.

Why use 3-second gust speed?

•

Extreme Winds Representation: The 3-second gust wind speed captures short bursts of intense wind,

which are typically the most damaging to structures. This makes it a critical parameter for designing

buildings and other structures to withstand extreme wind events.

•

Safety and Design Considerations: Since gusts represent the highest wind pressure a structure will

face; engineers use the 3-second gust speed to ensure the building's Main Wind Force Resisting System

(MWFRS) and components/cladding can handle these peak forces.

How it’s Applied in ASCE 7-16:

In the context of ASCE 7-16, the 3-second gust speed is used to calculate wind loads for structures. The Basic

Wind Speed (V) maps provided in the standard give 3-second gust wind speeds across different geographic

regions. This data is then used, along with factors like exposure category, building height, and terrain, to

determine the design wind loads for a building or structure.

In summary, the 3-second gust speed provides a standardized, extreme wind measurement that ensures

structures are designed to handle the highest expected wind pressures in a given region.

BUILDING, ENCLOSED:

In the context of ASCE 7-16, a Building, Enclosed is defined as a structure that meets specific criteria for the

protection of its interior from external wind forces. For a building to be classified as enclosed, the following

conditions must be met:

Definition: A Building, Enclosed is one where:

1. Openings in the Building Envelope (such as doors, windows, and vents) do not exceed a certain

threshold compared to the total surface area of the walls and roof.

2. Ratio of Openings:

o

The area of openings in each wall of the building must be less than or equal to 4% of the total

area of that wall. This prevents excessive wind from entering the building during extreme wind

events.

o

Openings should be designed to stay closed during high wind conditions, such as through the

use of impact-resistant doors, windows, or protective systems.

Importance of Classification:

Classifying a building as enclosed helps determine how the wind pressure will act on the structure. In an

enclosed building:

•

Wind pressures are primarily exerted on the exterior walls, roof, and the building's structural frame.

•

It reduces the risk of wind pressure build-up inside the building, which can lead to structural failure if

large openings allow wind to enter freely.

Criteria for Enclosed Building:

A building is considered enclosed if, for each wall that experiences positive external pressure (typically

windward walls), the total area of openings satisfies the condition:

Ao < 0.01Ag or Ao < 4sq ft (0.37 m2), whichever is smaller

Where:

•

Ao is the area of the openings in the wall (e.g., doors, windows, vents).

•

Ag is the gross area of the wall (the entire surface area of the wall).

Explanation:

•

Ao < 0.01Ag: The total area of openings must be less than 1% of the gross wall area. This limits the size

of openings that allow wind to enter the building.

•

Or, 4 square feet (0.37 m²): If 1% of the wall area exceeds 4 square feet, the openings must still not

exceed 4 square feet, which serves as a cap.

This condition is applied to each individual wall exposed to wind pressure.

Implications:

1. Reduced Internal Pressure: An enclosed building has limited openings, which minimizes the amount

of wind entering the building, preventing internal pressure buildup that could cause structural damage.

2. Wind Load Calculation: The classification of a building as "enclosed" affects how wind loads are

calculated, focusing on external wind pressure, rather than internal pressures.

Summary:

For a building to be classified as enclosed under ASCE 7-16, it must have limited openings, and those openings

should be properly designed to remain sealed in extreme wind events. This classification impacts how wind

loads are calculated, focusing on external wind pressures and reducing the risk of internal wind pressure

damage.

Low-Rise Building

A Low-Rise Building in ASCE 7-16 is an enclosed or partially enclosed building that satisfies the following two

conditions:

1. Mean Roof Height (h) ≤ 60 feet (18 meters):

•

The mean roof height (h) is the average height of the roof above the ground level.

•

For a building to be classified as low-rise, this average height must be 60 feet (18 meters) or less.

2. Mean Roof Height (h) Does Not Exceed the Least Horizontal Dimension:

•

The least horizontal dimension refers to the shortest side of the building's footprint.

•

The mean roof height (h) must be less than or equal to the least horizontal dimension of the building.

This means that the building cannot be tall and slender; it must have a relatively flat and wide profile.

Implications:

•

Low-rise buildings typically have relatively simple aerodynamic shapes, making wind load calculations

less complex compared to taller buildings.

•

The design procedures for low-rise buildings, like the Envelope Procedure (Chapter 28 of ASCE 7-16),

are often simpler than those for taller or irregularly shaped structures. These procedures apply

predefined wind pressure coefficients based on the building’s shape and height.

Example:

•

A building with a mean roof height of 50 feet (15 meters) and a footprint where the shortest horizontal

dimension is 55 feet (16.7 meters) would qualify as a low-rise building.

•

However, if the mean roof height were 65 feet, it would no longer meet the low-rise classification.

In summary, a low-rise building is defined by having a mean roof height of 60 feet (18 meters) or less, and this

height must be less than or equal to the building's least horizontal dimension.

Open Building

In ASCE 7-16, an Open Building is defined as a structure where the majority of the walls are open, allowing

wind to pass through freely. Specifically, the following condition applies:

Definition of Open Building:

A Building, Open is one in which each wall that receives positive external pressure has at least 80% open

area. This is expressed mathematically as:

Ao ≥ 0.8Ag

Where:

•

Ao = the total area of openings in the wall, in square feet (ft²) or square meters (m²).

•

Ag = the gross area of the wall, in square feet (ft²) or square meters (m²).

Key Points:

1. 80% Open: For each wall exposed to wind, at least 80% of its area must be made up of openings (such

as large windows, doors, or open spaces).

2. Walls with Positive External Pressure: This refers to the walls that directly face the wind and receive

wind pressure on their surfaces.

Example:

•

If the gross area of a wall (Ag) is 100 square feet, the area of openings (Ao) must be at least 80 square

feet (80% of 100 sq ft) for the building to be classified as open.

•

If the area of openings is less than 80% of the wall's total area, the building would not meet the

requirements for an open building.

Implications for Wind Load:

•

Wind Load Calculations: Open buildings allow wind to pass through the structure, so the internal

pressures due to wind are different from enclosed or partially enclosed buildings. Wind loads on open

buildings focus more on the forces acting on individual structural elements rather than large, enclosed

surfaces.

•

Common Examples: Structures like open parking garages, stadiums, or buildings with large open bays

or storefronts are often classified as open buildings.

In summary, an open building is one where each wall that experiences wind pressure has openings that make

up at least 80% of the total wall area. This classification impacts how wind forces act on the structure and how

wind load calculations are conducted.

BUILDING, PARTIALLY ENCLOSED

In ASCE 7-16, a Partially Enclosed Building is defined by specific conditions related to the total area of

openings in its walls and roof. The criteria ensure that while the building has some level of enclosure, it also

allows for wind pressure to enter, resulting in unique structural considerations. Here’s a breakdown of the

definition:

Definition of Partially Enclosed Building:

A Building, Partially Enclosed complies with both of the following conditions:

1. Openings in the Wall:

o

The total area of openings in a wall that receives positive external pressure (Ao) exceeds the

sum of the areas of openings in the balance of the building envelope (walls and roof) by more

than 10%.

o

This is mathematically expressed as:

Ao > 1.10Aoi

Where:

o

Aoi = sum of the areas of openings in the building envelope (walls and roof) not including Ao.

2. Total Area of Openings:

o

The total area of openings in a wall that receives positive external pressure must exceed 4 ft²

(0.37 m²) or 1% of the area of that wall, whichever is smaller.

o

Additionally, the percentage of openings in the balance of the building envelope must not

exceed 20%.

o

This is expressed as:

Ao > 0.01Ag or Ao > 4sq ft (0.37 m2), whichever is smaller

Aoi/Agi ≤ 0.2

Where:

o

Ag = the gross area of the wall that receives positive pressure.

o

Agi = sum of the gross surface areas of the building envelope (walls and roof) not including Ag.

Key Points:

•

Wind Pressure Effects: A partially enclosed building allows for some wind to enter, leading to

increased internal pressures, which must be considered in wind load calculations. The conditions

specified ensure that the structure is not completely open but allows enough openings to potentially

influence internal pressures.

•

Impacts on Design: The structural design must account for the wind forces acting on both the external

surfaces and the internal pressures resulting from wind entering the building through the openings.

Example:

•

•

Suppose a wall has:

o

Ao = 12ft2

o

The remaining building envelope has openings totaling Aoi = 9ft2.

The conditions would be checked as follows:

o

•

Check Condition 1: 12 ft2 >1.10×9 ft2 ⇒12 ft2 > 9.9ft2(True)

If the wall's gross area Ag is 100 ft²:

o

Check Condition 2: 12 ft2> 4ft2(True)

Also, 9/Total Building Envelope Area ≤0.20 (must be checked based on other data)

Summary:

A Partially Enclosed Building is characterized by having a significant amount of openings in one wall,

exceeding the openings in the remaining building envelope while still being limited in total openings. This

classification influences wind load calculations and necessitates specific design considerations to manage

internal and external pressures effectively.

Wind Directionality Factor (Kd) - ASCE 7-16

The Wind Directionality Factor (Kd) is a multiplier used to account for the variability of wind pressures in

different directions. It adjusts the calculated wind loads to reflect the reduced likelihood that the maximum

wind pressure will occur simultaneously in all directions. This factor is incorporated into wind load calculations

to provide a more accurate estimate of the wind effects on structures.

Key Points:

1. Determination of Kd:

o

The value of the Wind Directionality Factor (Kd) is obtained from Table 26.6-1 of ASCE 7-16.

Different types of structures and components have varying values of Kd based on their

geometry and exposure to wind from different directions.

2. Application in Wind Load Calculations (Chapters 27 to 30):

o

The Kd factor is used in wind load calculations for both the Main Wind Force Resisting System

(MWFRS) and Components and Cladding (C&C) as detailed in Chapters 27 (Directional

Procedure), 28 (Envelope Procedure), 29 (Directional Procedure for Building Appurtenances and

Other Structures), and 30 (Components and Cladding).

o

Wind loads are calculated using a formula where Kd modifies the basic wind pressures to

account for directionality:

F=qGCfAKd

Where:

•

F = wind force

•

q = velocity pressure

•

G = gust effect factor

•

C_f = force coefficient

•

A = area

•

Kd = wind directionality factor

•

Wind Tunnel Procedure (Chapter 31):

o

•

For buildings where wind tunnel testing is used (Chapter 31), the effect of wind directionality is

incorporated through rational analysis. This analysis must conform to the wind speed

requirements in Section 26.5.3 (determining basic wind speed) and Section 31.4.3 (rational

determination of wind loads using wind tunnel testing).

Rationale for Kd:

o

The Kd factor accounts for the fact that wind pressures are not uniform in all directions. For

instance, maximum wind forces typically act in specific directions, and the building's exposure

to wind may not be the same in all directions. The Kd factor reduces the calculated wind loads

to reflect this

Values of Kd (from Table 26.6-1):

The Wind Directionality Factor (Kd) varies depending on the structure type and component:

•

Buildings (MWFRS): 0.85

•

Chimneys, Tanks, Trussed Towers: 0.85

•

Trussed Towers Supporting Electric Transmission Lines: 0.9

•

Other Structures (Solid Signs, Open Signs, Lattice Frameworks, etc.): 0.85

•

Components and Cladding (C&C): 0.85

Example:

For a building with a Main Wind Force Resisting System (MWFRS):

•

Kd = 0.85

•

If the basic wind force is calculated to be 500 kN, applying Kd would give:

F = 500 kN × 0.85 = 425 kN This reflects a reduction in wind load due to wind directionality.

Conclusion:

The Wind Directionality Factor (Kd) is a crucial component in wind load calculations under ASCE 7-16,

reflecting the reduced likelihood that maximum wind pressure will occur uniformly in all directions. It adjusts

the wind loads for different structures and components based on their exposure to wind from varying

directions.

Exposure - ASCE 7-16 (26.7)

In ASCE 7-16, Exposure refers to the characterization of a building or structure’s surrounding terrain, which

impacts how wind pressures are calculated. The surrounding terrain influences wind speeds due to surface

roughness caused by natural or man-made obstructions like hills, trees, or buildings. Exposure affects the

wind velocity profile, and hence, the design wind loads for structures.

Key Points of Section 26.7:

1. Upwind Exposure:

o

For each wind direction being considered, the upwind exposure (the terrain in the direction

from which the wind is blowing) must be determined.

o

The ground surface roughness is the critical factor for defining the exposure category, which

varies based on the nature of the terrain upwind of the structure.

2. Ground Surface Roughness:

o

The ground surface roughness depends on both natural and man-made features that obstruct

wind flow. The roughness affects how wind speeds change as they move from open, flat terrain

to more built-up or rougher areas.

o

The exposure is typically evaluated for a distance of 1,500 feet (460 m) or more upwind of the

building or structure, depending on the feature’s influence on wind flow.

Exposure Categories:

The standard defines three main Exposure Categories (B, C, and D) based on the roughness of the terrain.

These categories affect how the wind load is calculated by considering how the terrain reduces or amplifies

wind speed.

1. Exposure B:

o

Represents urban and suburban areas with buildings, trees, or other structures covering at

least 20% of the ground surface for at least a distance of 1 mile (1,600 meters) or more.

o

This category applies to locations where buildings or obstructions reduce wind speed

significantly.

2. Exposure C:

o

o

This is the default exposure for open terrain with scattered obstructions. It includes areas like:

Open flat terrain (fields, farmland).

Grasslands or sparsely populated rural areas.

Airports and open spaces.

Exposure C applies to structures in areas without significant obstruction, leading to higher

wind speeds.

3. Exposure D:

o

Applies to structures near large bodies of water, such as oceans, large lakes, or expansive

coastal areas.

o

This category results in the highest wind speeds because water provides minimal surface

roughness to slow down wind.

o

It applies to areas with open water exposure for at least 1 mile (1.6 km) in the upwind direction.

Changes in Exposure:

•

If the terrain changes drastically over the upwind distance (such as transitioning from an urban area to

open water), the effective exposure category may be determined based on the dominant terrain

feature.

Conclusion:

Section 26.7 of ASCE 7-16 establishes that the upwind exposure for each wind direction must be based on the

ground surface roughness, which plays a crucial role in determining wind loads. The roughness of the terrain

upwind of the structure is classified into Exposure Categories B, C, and D, each representing different levels

of obstructions to the wind.

Wind Directions and Sectors (ASCE 7-16)

For determining wind loads, wind direction is crucial, as wind effects can vary significantly depending on the

terrain upwind of the structure. The exposure category, which determines how terrain affects wind speeds,

must be calculated based on the upwind sectors from which the wind is expected to approach the structure.

Key Aspects of Wind Directions and Sectors:

1. Two Upwind Sectors (45° each):

o

For each wind direction considered, two upwind sectors, extending 45° on either side of the

selected wind direction, must be evaluated.

o

This means that for each direction, the wind exposure must be assessed over a 90° range.

2. Selection of Exposure:

o

The highest wind loads from these sectors must be used for the structural design.

o

The exposure category that results in the largest wind loads will govern for that particular wind

direction.

Surface Roughness Categories (ASCE 7-16)

The surface roughness of the terrain upwind of the building plays a significant role in determining wind

exposure categories. The rougher the surface, the lower the wind speeds at ground level, while smoother

terrain allows higher wind speeds to develop.

Surface Roughness Categories:

1. Surface Roughness B:

o

Applies to urban and suburban areas.

o

Terrain with numerous, closely spaced obstructions, such as buildings or trees, which are the

size of single-family homes or larger.

o

Typical areas include densely built-up zones or heavily wooded areas.

2. Surface Roughness C:

o

Represents open terrain with scattered obstructions, generally less than 30 ft (9.1 m) in

height.

o

Includes flat, open country or grasslands.

o

This is the most common exposure category for lightly populated rural areas.

3. Surface Roughness D:

o

For flat, unobstructed areas and water surfaces.

o

Includes smooth mud flats, salt flats, unbroken ice, and open bodies of water.

o

Wind speeds are highest in this category because there are minimal obstructions to disrupt

wind flow.

Summary:

In designing structures for wind loads, it is essential to assess the exposure category for each wind direction by

evaluating two 45° upwind sectors. The exposure category that results in the highest wind load will be used

for structural design. The surface roughness of the terrain in these sectors is classified as Surface Roughness

B, C, or D, based on the nature and density of obstructions present.

•

Roughness B: Urban/suburban, densely built or wooded.

•

Roughness C: Open, rural terrain with scattered obstructions.

•

Roughness D: Flat, unobstructed areas like water bodies or plains.

By following this method, engineers ensure that buildings and structures are appropriately designed to

withstand wind forces based on the terrain conditions.

Exposure B (ASCE 7-16)

Exposure B is one of the key categories used in wind load calculations to account for the surface roughness

and its effects on wind velocity. It specifically applies to areas with a mix of buildings, trees, or other

obstructions that slow down wind speed. The criteria for applying Exposure B vary depending on the height of

the building or structure.

Criteria for Exposure B:

1. For Buildings or Structures with Mean Roof Height ≤ 30 ft (9.1 m):

o

Exposure B applies when the surrounding terrain exhibits Surface Roughness B for a distance

greater than 1,500 ft (457 m) in the upwind direction.

o

Surface Roughness B refers to urban or suburban areas with obstructions like buildings and

trees, covering at least 20% of the ground surface.

2. For Buildings or Structures with Mean Roof Height > 30 ft (9.1 m):

o

o

Exposure B applies when Surface Roughness B prevails in the upwind direction for a distance

greater than:

2,600 ft (792 m), or

20 times the height of the building or structure, whichever is greater.

This longer distance reflects the need for greater upwind obstruction to impact taller buildings

or structures, as wind has more space to accelerate over greater heights.

Key Definitions:

•

Mean Roof Height: The average height of the roof of the building from the ground.

•

Surface Roughness B: Represents urban, suburban, or wooded areas where buildings or trees cover at

least 20% of the land surface for an extended distance.

Example:

For a building with a mean roof height of 40 ft (12 m):

•

To use Exposure B, the upwind distance with Surface Roughness B must be at least:

Distance=20×Height=20×40 ft=800 ft(244 m)

Since 2,600 ft is greater than 800 ft, the required upwind distance for applying Exposure B is 2,600 ft

(792 m).

Conclusion:

Exposure B is applied in areas with significant surface roughness, such as urban or suburban settings. For lowrise buildings (≤ 30 ft), an upwind distance of 1,500 ft with Surface Roughness B is sufficient, but for taller

structures, the distance requirement increases to 2,600 ft or 20 times the building height, whichever is greater.

This category helps in calculating more accurate wind loads by considering the effects of surrounding

obstructions.

Exposure C (ASCE 7-16)

Exposure C is a catch-all category for areas that don't meet the criteria for Exposure B (urban, suburban, or

wooded areas) or Exposure D (open water or flat, unobstructed terrain). It typically applies to open terrain with

scattered obstructions, such as rural areas or lightly populated regions.

Criteria for Exposure C:

1. General Application:

o

Exposure C applies in all locations where Exposure B or Exposure D does not apply.

o

This exposure is typically used for:

Open terrain with scattered obstructions.

Areas with moderate surface roughness, such as open fields, grasslands, or sparsely

developed areas with a few buildings or trees.

2. Example Locations:

o

Rural areas with few trees or buildings.

o

Light industrial zones with scattered structures.

o

Areas with farmland or natural open spaces that still have some isolated obstructions.

3. Default Category:

o

If an area does not clearly fall into Exposure B or Exposure D, it is generally classified as

Exposure C.

o

This makes Exposure C the most commonly used category for a variety of sites that fall

between highly developed urban areas and wide open, flat regions.

Key Definitions:

•

Surface Roughness C: Terrain that has moderate roughness due to scattered obstructions, but not as

dense or smooth as Surface Roughness B or Surface Roughness D.

Example:

For a building located in a rural area with some small hills and scattered trees but no large water bodies or

dense urban development, Exposure C would apply because the terrain doesn't meet the conditions for

Exposure B (dense development) or Exposure D (flat, unobstructed terrain like open water).

Conclusion:

Exposure C is the default category used for open areas with scattered obstructions and moderate roughness.

It is applied in all cases where the site does not qualify for the more specific Exposure B or Exposure D

categories. This exposure represents a typical wind environment for many rural or lightly developed locations.

Exposure D (ASCE 7-16)

Exposure D refers to areas where the surrounding terrain has minimal surface roughness, such as large bodies

of water or flat, unobstructed areas. This exposure category results in the highest wind speeds because there

are fewer obstructions to slow down wind as it approaches a building or structure.

Criteria for Exposure D:

1. Primary Application:

o

Exposure D applies when Surface Roughness D (minimal roughness, like open water) prevails

in the upwind direction for a distance greater than 5,000 ft (1,524 m) or 20 times the height of

the building or structure, whichever is greater.

o

Surface Roughness D typically represents terrains such as:

Oceans

Large lakes or wide rivers

Coastal areas with large, unobstructed stretches of water

2. Application in Transitional Zones:

o

Exposure D can also apply when the ground surface roughness near the site is Exposure B or

C, but the site is located within:

o

600 ft (183 m) or 20 times the building or structure height, whichever is greater, from

an Exposure D condition (such as a large body of water).

In these cases, the wind flow may have had sufficient unobstructed space to accelerate,

requiring the use of Exposure D for wind load calculations.

3. Transition Zones Between Exposure Categories:

o

If a site is located in an area where multiple exposure categories (B, C, or D) are present in

different directions, the exposure category that results in the highest wind forces must be

used for design purposes. This ensures that the design is based on the most critical wind

loading condition.

Key Definitions:

•

Surface Roughness D: Represents terrains with very little obstruction to wind flow, typically large

bodies of water or open, flat areas with minimal terrain features.

•

Upwind Distance: The length of terrain in the direction the wind is blowing from, which impacts how

much wind acceleration can occur before hitting the structure.

Example:

For a building with a height of 100 ft (30.5 m) located near an ocean:

•

The upwind distance required for Exposure D would be the greater of:

o

5,000 ft (1,524 m), or

o

20 times the building height, which is:

20×100 ft=2,000 ft(610 m)

o

In this case, 5,000 ft is greater than 2,000 ft, so Exposure D would apply if the upwind distance

is at least 5,000 ft from the building.

Conclusion:

Exposure D represents areas with minimal terrain roughness, such as open water or coastal regions, where

wind speeds are highest. It applies when the upwind terrain meets specific distance criteria (5,000 ft or 20

times the building height). In cases where multiple exposures exist near a site, the exposure resulting in the

greatest wind forces should be used to ensure conservative wind load design.

Exception for Intermediate Exposure Zones (ASCE 7-16)

An exception exists in ASCE 7-16, allowing for the use of an intermediate exposure category in areas that lie

in a transition zone between two different wind exposure categories, such as between Exposure B, C, or D.

This flexibility is provided to account for cases where the terrain conditions do not clearly fit into a single

exposure category.

Key Points of the Exception:

1. Transition Zones:

o

A transition zone is an area where the terrain changes gradually between different wind

exposure categories, such as from urban (Exposure B) to open terrain (Exposure C), or from

open terrain (Exposure C) to flat, unobstructed areas like coastlines (Exposure D).

2. Rational Analysis Method:

o

An intermediate exposure category can be assigned if determined through a rational analysis

method supported by recognized literature.

o

This method must consider the gradual changes in terrain roughness and how it affects wind

flow and speed.

o

The analysis should account for factors such as changes in surface roughness, building heights,

and distances upwind in the prevailing wind direction.

3. Application of Intermediate Exposure:

o

When the transition between two exposure categories is gradual and not abrupt, the designer

can use an intermediate exposure based on the specific characteristics of the site.

o

This could result in a more accurate wind load calculation, considering that the actual wind

effects might not align perfectly with the strict definitions of Exposure B, C, or D.

Example:

For a building located in a suburban area (Exposure B) that transitions to a nearby rural, open area (Exposure

C), the site may be within a transition zone. If the distance upwind and terrain changes are gradual, an

intermediate exposure category between B and C might be more appropriate, depending on the results of a

rational analysis.

Conclusion:

This exception allows designers to account for complex site conditions that fall between two standard

exposure categories. By performing a rational analysis, they can justify using an intermediate exposure for

more precise wind load calculations. This flexibility ensures that wind loads are neither overestimated nor

underestimated for transitional terrain conditions.

Exposure Requirements (ASCE 7-16)

The exposure category defines the wind environment around a building or structure based on the terrain. In

ASCE 7-16, exposure requirements for wind load calculations vary depending on the procedure used for the

design of the Main Wind Force Resisting System (MWFRS) or Components and Cladding (C&C). Each design

approach—whether it is the Directional Procedure, Envelope Procedure, or the design of appurtenances and

other structures—requires a specific way of determining the exposure category.

26.7.4.1 Directional Procedure (Chapter 27)

•

•

For Enclosed and Partially Enclosed Buildings:

o

Wind loads calculated using the Directional Procedure (as outlined in Chapter 27) must be

based on the exposures defined in Section 26.7.3.

o

The exposure for each wind direction considered must be evaluated.

For Open Buildings (Monoslope, Pitched, or Troughed Free Roofs):

o

Wind loads should be determined based on the exposure category that results in the highest

wind loads for any given wind direction at the site.

This ensures that the building design accounts for the worst-case wind conditions for all potential wind

directions.

26.7.4.2 Envelope Procedure (Chapter 28)

•

Low-Rise Buildings:

o

When using the Envelope Procedure (as outlined in Chapter 28) for low-rise buildings, wind

loads for the design of the MWFRS should be based on the exposure category that results in

the highest wind loads for any wind direction.

This approach simplifies the wind load design for low-rise buildings, ensuring that the design is robust enough

to handle the highest possible wind forces regardless of direction.

26.7.4.3 Directional Procedure for Building Appurtenances and Other Structures (Chapter 29)

•

For Building Appurtenances and Other Structures (Rooftop Equipment, Freestanding Signs,

Chimneys, etc.):

o

Wind loads calculated using the Directional Procedure (outlined in Chapter 29) must be based

on the appropriate exposure category for each wind direction considered.

This ensures that wind loads on specific structures and building features are accurate for their particular

location and wind exposure.

26.7.4.4 Components and Cladding (Chapter 30)

•

For Components and Cladding (C&C):

o

Design wind pressures for C&C elements must be calculated using the exposure category that

results in the highest wind loads for any wind direction at the site.

This guarantees that the C&C of the building is designed to withstand the most extreme wind pressures it may

encounter, providing safety and structural integrity for the building's external elements.

Summary:

•

Directional Procedure (Chapter 27): Enclosed and partially enclosed buildings must use exposure

categories from Section 26.7.3, considering all wind directions. For open buildings, the exposure

category resulting in the highest wind load governs.

•

Envelope Procedure (Chapter 28): Low-rise buildings must use the exposure category that results in

the highest wind load for any wind direction.

•

Building Appurtenances and Other Structures (Chapter 29): Wind loads for these elements must

consider the appropriate exposure for each wind direction.

•

Components and Cladding (Chapter 30): Wind loads should be based on the highest wind loads from

any wind direction.

This framework ensures that all wind loads are calculated conservatively, accounting for the maximum forces a

building or structure may experience.

Topographic Effects (ASCE 7-16)

Understanding the effects of topography on wind loads is essential in the design of structures. The ASCE 7-16

provides guidelines to account for wind speed-up effects due to changes in terrain, such as hills, ridges, and

escarpments. Here’s a breakdown of Section 26.8, focusing on wind speed-up effects:

26.8.1 Wind Speed-Up over Hills, Ridges, and Escarpments

•

Definition of Wind Speed-Up Effects:

o

•

Wind speed-up effects occur when the wind encounters abrupt changes in the terrain, such as

isolated hills, ridges, and escarpments. These features can cause an increase in wind velocity

due to the acceleration of airflow as it moves over the elevated surfaces.

Inclusion in Wind Load Determination:

o

Wind speed-up effects must be considered in the calculation of wind loads when the site is

located near or on these topographic features, regardless of the exposure category in which

they fall.

o

The impact of these effects on the wind loads may vary depending on the height and steepness

of the terrain feature and the wind direction relative to the topography.

Key Considerations for Wind Speed-Up:

1. Terrain Analysis:

o

Conduct a detailed analysis of the site’s topography, identifying any hills, ridges, or

escarpments that may influence wind flow.

o

The topographic features should be evaluated for their height, slope, and location relative to the

structure being designed.

2. Wind Direction:

o

Assess how different wind directions may interact with the topographic features.

o

Wind speed-up effects can vary significantly with changes in wind direction, which can alter the

flow pattern around the terrain.

3. Modeling and Calculations:

o

Use computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models or wind tunnel testing to accurately predict

wind behavior over the topographic features.

o

Refer to appropriate methodologies outlined in ASCE 7-16 or relevant wind engineering

literature to quantify the speed-up effects.

4. Application of Speed-Up Factors:

o

Apply speed-up factors to the basic wind speed, VV, when calculating design wind loads.

o

The factors will adjust the wind speed to reflect the increased pressures resulting from the

topographic effects.

5. Design Implications:

o

Ensure that structural designs incorporate these increased wind loads to maintain safety and

performance.

o

Consider additional reinforcements or modifications to address the potential for higher wind

pressures due to topographic influences.

In addition to the previously discussed wind speed-up effects over hills, ridges, and escarpments, the ASCE 716 outlines specific conditions under which these effects must be included in wind load calculations. Here is a

detailed explanation of these conditions and the calculation of the topographic factor KztK_{zt}Kzt.

Conditions for Wind Speed-Up Effects (26.8.1)

To determine whether wind speed-up effects should be considered, all the following conditions must be

satisfied:

1. Isolation of Topographic Features:

o

The hill, ridge, or escarpment must be isolated and unobstructed by other similar features of

comparable height for a distance of 100 times the height of the topographic feature (100H) or 2

miles (3.22 km), whichever is less.

o

This distance is measured horizontally from the point at which the height H of the feature is

determined.

2. Height Protrusion:

o

The hill, ridge, or escarpment must protrude above the height of any upwind terrain features

within a 2-mile (3.22 km) radius in any quadrant by a factor of 2 or more.

3. Location of the Structure:

o

The building or structure should be situated in the upper half of a hill or ridge or near the crest of

an escarpment, as illustrated in Fig. 26.8-1 of ASCE 7-16.

4. Height-to-Length Ratio:

o

The ratio H/Lh must be greater than or equal to 0.2, where Lh represents the horizontal

distance from the base of the hill or ridge to the point where the height H is measured.

5. Minimum Height Requirements:

o

The height H of the hill, ridge, or escarpment must be at least 15 ft (4.5 m) for Exposure C and

D, and 60 ft (18 m) for Exposure B.

Topographic Factor Kzt (26.8.2)

When the above conditions are met, the wind speed-up effect is included in the design wind load calculations

by applying the topographic factor Kzt, calculated as follows:

Kzt = ( 1 + K1K2K3)2 (26.8−1)

Where:

•

K1,K2,K3 are factors determined from Fig. 26.8-1 based on the site conditions, topography, and wind

characteristics.

If the conditions specified in Section 26.8.1 are not met, then:

Kzt = 1.0

This means that no wind speed-up effects are considered in the design, and the basic wind speed is used

without modification.

Conclusion:

Understanding and applying the conditions outlined in Section 26.8 is critical for accurately assessing wind

loads on structures situated near topographic features. The calculation of the topographic factor Kzt allows

engineers to account for potential increases in wind speeds caused by hills, ridges, and escarpments. By

adhering to these guidelines, designers can ensure the safety and resilience of structures in varied terrain.

Ground Elevation Factor

The Ground Elevation Factor (Ke) is an important parameter in the wind load calculation process as outlined

in ASCE 7-16. It accounts for variations in air density due to changes in elevation above sea level, which can

affect the design wind speeds and subsequently the wind loads acting on structures.

1. Purpose of the Ground Elevation Factor (Ke)

•

The primary purpose of Ke is to adjust the basic wind speed based on the elevation of the building or

structure relative to sea level.

•

As elevation increases, air density decreases, which can influence wind behavior and loads.

2. Calculation of Ke

•

The ground elevation factor Ke is determined using Table 26.9-1 provided in the ASCE 7-16 standard.

This table typically contains values of Ke based on specific elevations and may provide guidance for

various design situations.

3. Assumption of ( Ke = 1)

•

In cases where the air density variation is negligible or for elevations where precise adjustments are not

critical, it is permitted to assume: Ke=1

•

This simplification can be used for all elevations without making any corrections for air density.

4. Practical Application

When performing wind load calculations:

•

If the elevation of the structure is such that significant air density effects are expected (usually at higher

elevations), the appropriate Ke value from the table should be utilized.

•

For structures located at or near sea level or in areas where elevation does not exceed typical ranges,

using Ke = 1 simplifies the calculation while still providing conservative results.

Conclusion

Incorporating the Ground Elevation Factor Ke in wind load calculations is essential for ensuring accurate

design considerations based on local conditions. By utilizing the specified values from Table 26.9-1, or opting

for Ke = 1 when appropriate, engineers can effectively address variations in air density and enhance the safety

and performance of structures subjected to wind forces.

Velocity Pressure Exposure Coefficient

The Velocity Pressure Exposure Coefficient (Kz or Kh) is a critical factor in determining the wind pressure

acting on structures as per the guidelines established in ASCE 7-16. This coefficient is influenced by the

exposure category of the site, which is defined in Section 26.7.3 based on the surrounding terrain and surface

roughness.

2. Determination of Kz or Kh

•

The values for Kz or Kh are obtained from Table 26.10-1, which specifies the coefficients based on the

determined exposure category (A, B, C, or D) as outlined in Section 26.7.3.

•

These coefficients will vary depending on the building height and the surrounding terrain

characteristics.

3. Application in Transition Zones

•

For sites that lie in a transition zone between different exposure categories:

o

Engineers are permitted to use intermediate values of Kz or Kh that fall between those listed in

Table 26.10-1.

o

The selection of these intermediate values must be based on a rational analysis method

defined in recognized literature, ensuring that the analysis accurately reflects the specific

conditions of the site.

4. Practical Considerations

When applying Kz or Kh in wind load calculations:

•

Identify the exposure category of the site based on surrounding terrain and surface roughness.

•

Refer to Table 26.10-1 to determine the appropriate coefficient.

•

If the site is in a transition zone, conduct a rational analysis to justify any intermediate values used.

Conclusion

The Velocity Pressure Exposure Coefficient Kz or Kh is essential for accurately calculating wind pressures on

structures, considering the effects of surrounding terrain. By using the specified coefficients from Table 26.101, or justified intermediate values in transition zones, engineers can ensure that their designs are robust and

appropriate for the specific wind conditions expected at the site.

Velocity Pressure

The velocity pressure (qz ) at a specific height (z) above the ground is a crucial calculation for assessing the

wind loads acting on structures. This pressure is derived from the basic wind speed and adjusted for several

factors that account for the structure's exposure, topography, wind direction, and ground elevation.

1. Velocity Pressure Equation

The velocity pressure can be calculated using the following equations:

•

In pounds per square foot (lb/ft²):

qz =0.00256KzKztKdKeV2 (lb∕ft2) ; V in mi∕h (26.10-1)

•

In newtons per square meter (N/m²):

qz =0.613KzKztKdKeV2 (N∕m2) ; V in m∕s (26.10-1 si)

Where:

Kz = velocity pressure exposure coefficient, see Section 26.10.1.

Kzt = topographic factor, see Section 26.8.2.

Kd = wind directionality factor, see Section 26.6.

Ke = ground elevation factor, see Section 26.9.

V = basic wind speed, see Section 26.5.

qz = velocity pressure at height z.

Calculation of Velocity Pressure at Mean Roof Height

•

The velocity pressure at the mean roof height (qh) can be specifically computed by substituting the

mean roof height into the equation:

qh = qz evaluated from Eq. (26.10-1) using Kz at mean roof height h

This step ensures that the wind pressures are accurately accounted for based on the specific height of the roof,

considering how wind behaves differently at varying elevations.

Gust Effects

The gust-effect factor is introduced to account for the fluctuating nature of wind forces caused by gusts,

which can increase the instantaneous wind loads on a structure.

26.11.1 Gust-Effect Factor for Rigid Structures

•

Rigid Buildings and Structures: For rigid buildings or other structures, the gust-effect factor GGG is

permitted to be taken as 0.85.

This simplification applies to buildings that do not exhibit significant dynamic responses to wind forces, such

as shorter or stiffer structures where wind-induced vibrations are minimal.

Key Considerations:

•

The gust-effect factor is typically used in conjunction with the basic wind pressure to adjust for the

increased loads that gusts impose.

•

For non-rigid or dynamically sensitive structures, the gust-effect factor would need to be evaluated

using more detailed procedures outlined in other sections, as these structures can amplify wind forces

through resonance.

Conclusion

For most rigid buildings, assuming a gust-effect factor of 0.85 simplifies the calculation of wind loads.

However, for taller or more flexible structures, a more detailed analysis of gust effects may be required.

Frequency Determination

To classify a building or structure as rigid or flexible according to the definitions provided in Section 26.2, the

following steps must be followed:

•

Fundamental Natural Frequency n1: This frequency is determined by analyzing the structural

properties and deformational characteristics of the elements that resist the wind forces. A properly

substantiated structural analysis must be conducted to establish n1n_1n1.

•

Rigid vs. Flexible:

•

o

Buildings and structures with a fundamental frequency ( n1 ≥ 1 Hz are considered rigid.

o

Those with a frequency ( n1 < 1 Hz are considered flexible and may require a more detailed

gust-effect analysis.

Low-Rise Buildings: Low-rise buildings, as defined in Section 26.2 (mean roof height h ≤ 60ft and

height not exceeding the least horizontal dimension), are permitted to be considered rigid by default,

simplifying the wind load analysis for these structures.

Key Takeaways:

•

Rigid buildings experience minimal dynamic effects from wind, allowing the use of simplified

procedures (e.g., gust-effect factor G=0.85).

•

Flexible buildings require more detailed dynamic wind analysis, considering the increased response to

wind-induced oscillations.

Conclusion

The determination of a building's fundamental natural frequency is crucial in classifying it as rigid or flexible.

For low-rise buildings, a simplified approach may be applied, treating them as rigid without a detailed

frequency analysis. However, for taller or more complex structures, frequency analysis is essential for accurate

wind load calculations.

Approximate Natural Frequency

The approximate lower bound natural frequency (na), in hertz, of concrete or structural steel buildings that

comply with the conditions specified in Section 26.11.2.1 can be calculated using one of the following

equations. These equations provide a simplified method for estimating the fundamental natural frequency

without the need for detailed dynamic analysis.

For structural steel moment-resisting frame buildings,

na =22.2∕h0.8 (26.11-2)

For concrete moment-resisting frame buildings,

na =43.5∕h0.9 (26.11-3)

For structural steel and concrete buildings with other lateral force-resisting systems,

na =75∕h (26.11-4)

For concrete or masonry shear wall buildings, it is also permitted to use

na = 385(Cw)0.5∕h (26.11-5)

where

h = mean roof height, ft (m).

n = number of shear walls in the building effective in resisting

lateral forces in the direction under consideration.

AB = base area of the building, ft2 (m2).

Ai = horizontal cross-sectional area of shear wall i, ft2 (m2).

Di = length of shear wall i, ft (m).

hi = height of shear wall i, ft (m).

Limitations for Approximate Natural Frequency (na)

When determining the natural frequency (na) of a building, two key limitations must be met:

•

Building Height Limitation:

o

•

The height of the building should not exceed 300 ft (91 m). This limitation ensures that the

behavior of the building under wind loads can be approximated accurately without considering

more complex dynamic responses that are more pronounced in taller structures.

Effective Length Condition:

o

The height of the building must be less than 4 times its effective length (Leff). This condition

relates to how the building responds to wind forces and how the stiffness and flexibility of the

structure are balanced.

2. Effective Length Calculation

The effective length (Leff) is calculated to understand the dynamic response of a building under wind loads. It is

defined as:

Breakdown of the Equation:

•

hi: This is the height above grade of level iii. It represents how high the level is from the ground.

•

Li: This is the length of the building at level iii in the direction parallel to the wind. It captures the

horizontal extent of the structure at that height.

•

n: This is the total number of levels in the building.

Example:

Steps to Calculate Leff :

1. Determine the Height and Length:

o

For each level i, measure the height hi and the length Li.

2. Calculate the Numerator:

o

Multiply each height hi by its corresponding length Li and sum all these products:

Numerator = ∑

ℎ

Denominator = ∑

ℎ

Calculate the Denominator:

o

Sum all the heights:

et’s say we have a 3-story building with the following measurements:

Level (i)

Height (hi)

Length (Li)

1

10 ft

40 ft

2

10 ft

40 ft

3

15 ft

40 ft

Calculate the numerator:

Numerator=(10×40)+(10×40)+(15×40)=400+400+600=1400 ft2

Calculate the denominator:

Denominator=10+10+15=35 ft\text{Denominator} = 10 + 10 + 15 = 35 ft

Compute Leff :

Leff = 1400 / 35=40 ft

By ensuring that the building height is less than 300 ft and that the height is less than 4 times Leff. *