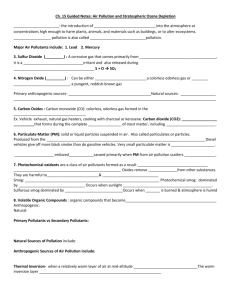

ENG’G 510 – Air and Noise Pollution Control (Field Study) Term: Summer, 4th Year Professor: Engr. Marilyn M. Nacpil AIR POLLUTION: Subject Overview A. AIR POLLUTION AND ITS TYPES 1. History of Air Pollution and Its Types One of the culprits is fire, one of the oldest forms — if not the oldest form — of air pollution around. Before humans even entered the scene, natural forest fires sparked by lightning caused air pollution. Today wildfires still present a massive pollution problem and more. "The Indonesian forest fires today are a humanitarian disaster, causing more than 500,000 cases of reported respiratory illness (not including hundreds of thousands more of unreported illness)," says Jacobson. But manmade fires are also major polluters and have been for some time. Just read the history books. In 61 A.D. Lucius Annaeus Seneca, the Younger wrote, "As soon as I had gotten out of the heavy air of Rome, from the stink of the chimneys and the pestilence, vapors and soot of the air, I felt an alteration to my disposition." When the 16th-century Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo discovered California's San Pedro Bay, he reportedly noted that while the mountain peaks in the distance were visible, their bases were obscured by the smoke from Indian fires. Today in developing nations around the globe some three billion people use cookstoves that burn solid fuels, which create indoor air pollution thatleads to millions of premature deaths each year. Burning fossil fuels is, of course, another large source of air pollution. Ever since the advent of the Industrial Age, the growth of manufacturing has vaulted air pollution into new realms. Even with the great strides that the United States and Europe have made on the pollution-combating front, much work is needed to stem the tide of polluted air caused by today's smokestacks and tailpipes. (See the American Lung Association's State of the Air report for 2015 to see the best and worst cities for air pollution.) In cities like Beijing (as the 2008 Summer Games so starkly illustrated) and Lingfen in China and New Delhi people suffer on a daily basis from air pollution that is equivalent to smoking two to three packs of cigarettes a day. 2. Air Pollution: Definition and Types Air Pollution, Defined Defining “air pollution” is not simple. One could claim that air pollution started when humans began burning fuels. In other words, all man-made (anthropogenic) emissions into the air can be called air pollution, because they alter the chemical composition of the natural atmosphere. The increase in the global concentrations of greenhouse gases CO2, CH4, and N2O, can be called air pollution using this approach, even though the concentrations have not found to be toxic for humans and the ecosystems. One can refine this approach and only consider anthropogenic emissions of harmful chemicals as air pollution. However, this refined approach has some drawbacks. Firstly, one has to define what “harmful” means. “Harmful” could mean an adverse effect on the health of living things, an adverse effect on anthropogenic or natural non-living structures, or a reduction in the air’s visibility. Also, a chemical that does not cause any short-term effects may accumulate in the atmosphere and create a long-term harmful effect. For example, anthropogenic emissions of chlorofluorocarbons were once considered safe because they are inert in the lowest part of the atmosphere called the troposphere. However, once these chemicals enter the stratosphere, ultraviolet radiation can convert them into highly-reactive species that can have a devastating effect in the stratospheric ozone. Similarly, CO2 emissions from combustion processes were considered safe because they are not toxic, but the long-term accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere may lead to a climate change, which could then be harmful to human and the ecosystems. Another drawback of this approach is that it does not consider natural emissions as air pollution even though they can be very harmful, such as gases and particles from volcanic eruptions, and smoke from forest fires caused by natural phenomena. So besides the anthropogenic emissions, it is useful to also consider geogenic emissions and biogenic emissions as contributors to air pollution. Geogenic emissions are defined as emissions caused by the non-living world (i.e. volcanic emissions, sae-salt emissions, and natural fires). Biogenic emissions come from the living world; such as volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions fro forests and CH4 emissions from swamps. Human activity can also influence geogenic and biogenic emissions. For example, human applications of nitrogen fertilizers in agriculture can result in increased biogenic emissions of nitrogen compounds from the soil. Also, humans can affect the biogenic emissions of VOCs by cutting down trees or planting trees. Lastly, geogenic emissions from the earth’s surface can be altered if the surface is changed by human activity. So taking all of the above into account, we can define an “air pollutant as any substance emitted into the air from an anthropogenic, biogenic, or geogenic source, that is either not part of the natural atmosphere or is present in higher concentrations than the natural atmosphere, and may cause a short-term or long-term adverse effect. Types of Air Pollution There are two types of air pollution considered to be most hazardous to human health, by the American Lung association: the Ozone (or Smog); and the Particle Pollution. 1. Ozone (or Smog) is formed by a chemical reaction between sunlight and the vapors emitted by the burning od carbon-based or fossil fuels. Ozone pollution is generally at its highest during the sunniest months of the year. The pollutants can cause short-term health issues immediately following exposure, such as skin irritations, and respiratory problems such as impaired lung functions, inflammation of lung lining, and higher rates of pulmonary disease. 2. Particle pollution also takes a place at the top of the list of the most dangerous to human health, and is very widespread throughout the environment. This type of pollution consists of solid and liquid particles made up of ash, metal, soot, diesel exhaust, and chemicals. Particle pollution is produced by the burning of coal in power plants and other industries, and by the use of diesel fuel in passenger vehicles, cargo vehicles, and heavy equipments. Wood burning is also a source of particle pollution, and it is known to irritate respiratory conditions including asthma, and cause coughing, wheezing, and even shorter life spans. 3. Air Pollutants Pollutants can be classified as Primary or Secondary. Primary Pollutants are substances that are directly emitted into the atmosphere by sources. The main primary pollutants known to cause harm in high enough concentrations are the following: Carbon compounds such as CO, CO2, CH4, and VOCs Nitrogen compounds such as NO, N2O, and NH3 Sulfur compounds such as H2S, and SO2 Halogen compounds such as chlorides, fluorides, and bromides Particulate Matter (PM or aerosols), either in solid or liquid form, which is usually categorized into these groups based on the aerodynamic diameter of the particles: 1. Inhalable – particles which are less than 100 microns, and can also easily enter the nose and mouth. 2. Thoracic – particles that are less than 10 microns, and penetrate deep into the respiratory system. 3. Respirable – particles that are less than 4 microns, small enough to pass completely through the respiratory system and enter the bloodstream 4. Fine (as labeled in the USA) – particles that are less than 2.5 microns 5. Ultrafine – particles less than 0.1 microns in size Secondary Pollutants are not directly from sources, but instead, form in the atmosphere from primary pollutants (also called “precursors”). The main secondary pollutants known to cause harm in high enough concentrations are the following: NO2 and HNO3 formed from NO Ozone (O3) formed from photochemical reactions of nitrogen oxides and VOCs Sulfuric acid droplets formed from SO2, and nitric acid droplets formed from NO2 Sulfates and nitrates aerosols (e.g. ammonium (bi)sulfate and ammonium nitrate) formed from reactions of sulfuric acid and nitric acid droplets with NH3 respectively. Organic aerosols formed from VOCs in gas-to-particle reactions While nitrogen oxides are emitted by a wide variety of sources, automobiles mostly emit VOCs, even though the concentrations can be found from vegetation and common human activities, such as bakeries. Some secondary pollutants – sulfates, nitrates, and organic particles – can be transported over large distances, such as hundreds and even thousands of miles. Wet and dry deposition of these pollutants contributes to the “acid deposition” problem, or more often referred to as Acid Rain, with possible damage to soils, vegetation, and susceptible lakes. Classifications of Air Pollutants 1. Criteria Pollutants There are 6 principal criteria pollutants regulated by the US-EPA and most countries in the world. Total Suspended Particulate matter (TSP), which can exist in either solid or liquid form, and includes smoke, dust, aerosols, metallic oxides, and pollen. Sources of these include combustions, factories, construction, demolition, agricultural activities, motor vehicles, and wood burning. Inhalation of enough TSP over time increases the risk of chronic respiratory diseases. Sulfur dioxide (SO2). This compound is colourless, but has a suffocating, pungent odor. The primary source of SO2 is the combustion of sulfur-containing fuels (e.g. oil and coal). Exposure to SO2 can cause the irritation of lung tissues and can damage health and materials. Nitrogen oxides (NO and NO2) NO2 is a reddish-brown gas with a sharp odor. The primary source of this gas is vehicle traffic, and it plays a role in the formation of tropospheric ozone. Large concentrations can reduce visibility and increase the risk of acute and chronic respiratory disease. Carbon monoxide (CO). This odorless, odorless gas is formed from the incomplete combustion of fuels. Thus, the largest sources of CO today are motor vehicles. Inhalation of CO reduces the amount of oxygen in the bloodstream, and high concentrations can lead to headaches, dizziness, unconsciousness, and death. Ozone (O3). Troposhperic (low-level) ozone is a secondary pollutant formed when sunlight causes photochemical reactions involving NO and VOCs. Automobiles are the largest source of VOCs necessary for these reactions. Ozone concentrations tend to peak in the afternoon, and can cause eye irritations, aggravation of respiratory diseases, and damage to plants and animals. Lead (Pb). The largest source of lead in the atmosphere has been from leaded gasoline combustions, but with the gradual elimination worldwide, air Pb levels have decreased considerably. Other airborne sources include combustion of solid waste , coal, and oils, emissions from iron and steel production and lead smellers, and tobacco smoke. Exposure to Pb can affect the blood, kidneys, and nervous, immune, cardiovascular, and reproductive systems. 2. Toxic Pollutants Hazardous Air Pollutants (HAPs), also called Toxic Air Pollutants or Air Toxics, are those pollutants that cause or may cause cancer or other serious health effects, such as reproductive effects or birth defects. The US-EPA is required to control 188 HAPs. Examples of TAPs include benzene, which is found in gasoline, perchlorethylene, which is emitted from some dry cleaning facilities, and methylene chloride, which is used as a solvent and paint stripper by a number of industries. 3. Radioactive Pollutants Radioactivity is an air pollutant that is both geogenic and anthropogenic. Geogenic radioactivity results from the presence of radionuclides, which originate either from radioactive minerals in the earth’s crust or from the interaction of cosmic radiation with atmospheric gases. Anthropogenic radioactive emissions originate from nuclear reactors, the atomic energy industry (mining and processing of reactor fuel), nuclear weapon explosions, and plants that reprocess spent reactor fuel. Since coal contains small quantities of uranium and thorium, these radioactive elements can be emitted into the atmosphere from coal-fired power plants and other sources. 4. Indoor Pollutants When a building is not properly ventilated, pollutants can accumulate and reach concentrations greater than those typically found outside. This problem has received media attention as “Sick Building Syndrome”. Environmental tobacco smokes (ETs) is one of the main contributors to indoor pollution, as are NO, CO, and SO2, which can be emitted from furnaces and stoves. Cleaning or remodeling a house is an activity that can contribute to elevated concentrations of harmful chemicals such as VOCs emitted from household cleaners, paint, and varnishes. Also, when bacteria die, they release endotoxins into the air, which can cause adverse health effects. So ventilation is important when cooking, cleaning, and disinfecting a building, or simply homes. A geogenic source of indoor air pollution is radon. B. AIR POLLUTION MONITORING AND ANALYSIS 1. Ambient Air Pollution Monitoring Most frequently occurring pollutants in an urban environment are particulate matters (suspended particulate matter i.e. SPM and respirable suspended particulate matter i.e. RSPM), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrocarbons (HC), sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3) and photochemical oxidants. RECOMMENDED CRITERIA FOR SITING MONITORING STATIONS: 1. The site is dependent upon the use/purpose of the monitoring programs. 2. The monitoring should be carried out with a purpose of compliance of air quality standards. 3. Monitoring must be able to evaluate impacts of new/existing air pollution sources. 4. Monitoring must be able to evaluate impacts of hazards due to accidental release of chemicals. 5. Monitoring data may be used for research purpose. TYPES OF AMBIENT MONITORING STATIONS 1. Type A – Downtown Pedestrian Exposure Station: in central business districts, in congested areas, surroundings by buildings, many pedestrians, average traffic flow > 10,000 vehicles per day. Location of station: 0.5 m from curve; 2.5 to 3.5 m from the ground. 2. Type B – Downtown Neighborhood Exposure Station: in central business districts but not congested areas, less high rise buildings, average vehicles, <500 vehicles per day. Location of station: 0.5 m from curve; 2.5 to 3.5 m from the ground. 3. Type C – Residential Population Exposure Station: in the midst of the residential areas or sub-urban areas but not in central business districts. The station should be more than 100 m away from any street. 4. Type D – Mesoscale Stations: at appropriate height to collect meteorological and air quality data at upper elevation. Main purpose is to collect the trend of data variations and not human exposure. 5. Type E – Non-urban Stations: in remote non-urban areas. No traffic, no industrial activity. Main purpose is to monitor trend analysis. Location of station: 0.5 m from curve; 2.5 to 3.5 m from the ground. 6. Type F – Specialized Source Survey Stations: to determine the impact on air quality at specified location by an air pollution source under scrutiny. Location of station: 0.5 m from curve; 2.5 to 3.5 m from the ground. FREQUENCY OF DATA COLLECTION Gaseous Pollutants: continuous monitoring Particulates: once every three days NUMBER OF STATIONS Minimum number of stations is three. The location is dependent upon the wind rose diagram that gives predominant wind directions and speed. One station must be at upstream of predominant wind direction and other two must be at downstream of the predominant wind direction. More than three stations can also be established depending upon the area of coverage. COMPONENTS OF AMBIENT AIR SAMPLING SYSTEMS 1. Inlet Manifold – transports sampled pollutants from ambient air to collection medium or analytical device in an unaltered condition. The manifold should not be very long. 2. Air Mover – provides force to create vacuum or lower pressure at the end of the sampling systems, which serve as the system’s main pumps. 3. Collection Medium – liquid or solid sorbent or dissolving gases or filters or chamber for air analysis (automatic instruments). 4. Flow Measurement Device – like rotameters, they measure the volume of air sampled. CHARACTERISTICS FOR AMBIENT AIR SAMPLING SYSTEMS 1. Collection efficiency 2. Sample stability 3. Recovery 4. Minimal interference 5. Understanding the mechanism of collection The first three must be 100% efficient. E.g. for SO2, the sorbent should be such that at ambient temperature, it may remove the SO2 from the ambient atmosphere 100%. Sample must be stabled during the time between sampling and analysis. Recovery i.e. the analysis of particular pollutant must be 100%. BASIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR SAMPLING Sample must be representative in terms of time, location, and conditions to be studied. Sample must be large enough for accurate analysis. The sampling rate must be such as to provide maximum efficiency of collection. Duration of sampling must accurately reflect the fluctuations in pollution levels i.e. whether 1-hourly, 4hourly, 6-hourly, 8-hourly, 24-hourly sampling. Continuous sampling is preferred. Pollutants must not be altered or modified during collection. 2. Stack Monitoring SAMPLING The sample collected must be representative in terms of time and location The sample volume should be large enough to permit accurate analysis. The sampling rate must be such as to provide maximum efficiency of collection. The contaminants must not be modified or altered in the process of collection. SELECTION OF SAMPLING LOCATION The sampling point location should be as far as possible from any disturbing influence, such as elbows, bends, transition pieces, baffles. Wherever possible, it should be at a distance of 5-10 meters downstream from any obstruction and 3-5 meters upstream from similar disturbance. SIZE OF SAMPLING POINT The size of the sampling point may be made in the range of 7-10 cm in diameter. TRAVERSE POINTS For the sample to be representative, it should be collected at various points across the stack. The number of traverse points may be selected with reference to the following Cross-sectional area of stack (sq.m.) Number of points 0.2 4 0.2 to 2.5 12 2.5 and above 20 In circular stacks, traverse points are located at the center of equal annular areas across two perpendicular diameters. In case of rectangular stacks, the area may be divided in to 12 to 25 equal areas and the centers for each area are fixed. C. EXPERIMENTAL ANALYSIS The components of an air pollution monitoring system include the collection or sampling of pollutants both from the ambient air and from specific sources, the analysis or measurement of the pollutant concentrations, and the reporting and use of information collected. Emissions data collected from point source are used to determine compliance with air pollution regulations, determine the effectiveness of air pollution control technology, evaluate production efficiencies, and support scientific research. The EPA has established ambient air monitoring methods for the criteria pollutants, as well as for toxic organic (TO) compounds and inorganic (IO) compounds. The methods specify precise procedures that must be followed for any monitoring activity related to the compliance provisions of the Clean Air Act. These procedures also regulate sampling, analysis, calibration of instruments, and calculation of emissions. The concentration is expressed in terms of mass per unit volume, usually in micrograms per cubic meter. PARTICULATE MONITORING Particulate monitoring is usually accomplished with manual measurements and subsequent laboratory analysis. A particulate matter measurement uses gravimetric principles. Gravimetric analysis refers to the quantitative chemical analysis of weighing a sample, usually of a separated and dried precipitate. In this method, a filter-based high-volume sampler (a vacuum-type device that draws air through a filter or absorbing substrate) retains atmospheric pollutants for future laboratory weighing and chemical analysis. Particles are trapped or collected on filters, and the filters are weighed to determine the volume of the pollutant. The weight of the filter with collected pollutants minus the weight of a clean filter gives the amount of particulate matter in a given volume of air. Chemical analysis can be done by Atomic Absorption Spectometry (AAS), Atomic Fluorescence Spectometry, Inductive Couple Plasma (ICP) Spectroscopy, and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Spectroscopy. Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) AAS is a sensitive means for the quantitative determination of more than 60 metals or metalloid elements. This technique operates by measuring energy changes in the atomic state of the analyte. For example, AAS is used to measure lead in particulate monitoring. Particles are collected by gravimetric methods in a Teflon (PTFE) Filter, lead is acid-extracted from the filter. The aqueous sample is vaporized and dissociates into its elements in the gaseous state. The element being measured, as for this example, lead, is aspirated into a flame or injected into a graphite furnace and atomized. A hollow cathode or electrode-less discharge lamp for the element being determined provides a source of that metal’s particular absorption wavelength.