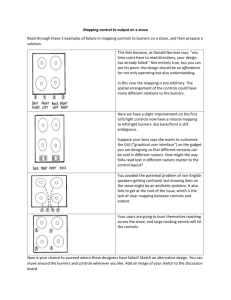

S w 9B02A013 GINO SA: DISTRIBUTION CHANNEL MANAGEMENT Alan (Wenchu) Yang prepared this case under the supervision of Professor Terry Deutscher solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality. Ivey Management Services prohibits any form of reproduction, storage or transmittal without its written permission. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Management Services, c/o Richard Ivey School of Business, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 3K7; phone (519) 661-3208; fax (519) 661-3882; e-mail cases@ivey.uwo.ca. Copyright © 2002, Ivey Management Services Version: (A) 2009-10-28 David Zhou, China marketing manager of Gino SA (Gino) put down the telephone receiver. He had been urged by his supervisor, Jean-Michel Pierre, Asia Pacific Area manager, to proceed with a potential original equipment manufacturer (OEM) customer and to resolve the confusion existing in the distribution channels. What are you waiting for, David? Just go there and sign the contract. I need this OEM, and I don’t need Jinghua to tell me what Gino should do. We obviously have some problems with our distributors. I don’t want them complaining in front of my boss at our global distributors’ meeting in April. You must do something David. Yes, right now. Bye! Three months ago, Zhou had been asked by Tianjin Feima Boiler Company (Feima) for permission to buy burners directly from Gino rather than from Jinghua Mechanical Engineering Company (Jinghua) — Gino’s largest distributor in China. Given the size and potential of the business, Zhou was excited by the initiative and he entered into discussions with Feima after receiving the consent of Jinghua. As the project progressed, however, Jinghua had become more and more aggressive in opposing the deal. Jinghua’s general manager, Henry Gong, even threatened to “reconsider the co-operation with Gino if Feima is touched.” Zhou was debating whether or not to proceed with the project. Pierre’s call reminded Zhou he could not afford delay. It was already February 25, 2000; in six weeks, the distributors were going to Paris to attend the company’s global distributors meeting where they would meet with Jean-Guy Picher, the director of the Commercial Department of Gino Burner. Page 2 9B02A013 BURNERS Products Burners were electromechanically controlled appliances that provided “controlled flame” for combustion applications such as boilers and furnaces. There were two major parts in a burner: the body and the head. The body contained the control system, consisting of the electric circuit, dumper, fan, valve, pump and control box. The control system was usually housed in a plastic and iron canopy, which was often painted in a bright color. The head was usually a heatproof carbon steel tube with nozzles. In field applications, the head was placed in the combustion chamber of the boiler or furnace and the body was left outside. The body was connected to a power cable and an oil or natural gas supply. Markets Most burners were used in various kinds of boilers, from small household units that provided heating and sanitary water (e.g., hot water for showers and dish washing) to high-output industrial boilers that generated steam or hot water for heating buildings connected by underground pipelines. Other applications included absorption chillers, industrial furnaces and ovens, ceramic kilns, car painting booths and other incineration appliances. There were different ways to partition the burner market, but Gino used output capacity as its primary segmentation variable. Domestic burners, typically matched with boilers of capacity up to 0.5 ton, were usually used for unit heating applications, such as individual households or sauna rooms. Commercial burners, which fired boilers typically with capacities of 0.5 tons to 2 tons, provided heating and sanitary water for small operations, such as offices, shops and restaurants. Industrial burners were usually used for large absorption-type chillers and boilers for applications in various industries. Europe was the single largest burner market in the world, followed by the United States. In recent years, however, the traditional markets (applications such as domestic and commercial heating and sanitary water) had become saturated. Their small annual sales increases could be attributed to inflation and population growth. In emerging markets such as Asia, the Middle East and parts of Africa, however, the market was growing rapidly. There was demand for all ranges of burners, especially the domestic and commercial products (see Table 1). Table 1: World Market for Burners 1999 (in thousands of units) Area Europe North America Asia Rest of world Total Market Size 574 433 291 250 1,548 Gino sales 276 45 36 24 381 Page 3 9B02A013 GINO SA Company Background Gino Burner Co., founded in 1931, was a manufacturer of burners, headquartered in Paris, France. It had a wide burner product line, covering the domestic, commercial and industrial ranges. In each segment, there were many models with varied outputs; in total, Gino manufactured over 50 models of burners. The company was best known for its domestic burners. The management of the company believed Gino enjoyed three competitive edges: in-house production capability, a well-established channel network and international exposure. The company was traditionally known in the market as providing the products of “best value.” Gino’s cost advantage was more obvious in smaller burners. In the domestic range, Gino burners were usually 10 per cent to 20 per cent lower in price than the major competitors, and in some extreme cases, the price gap could reach 30 per cent. In 1999, the company produced 381,000 burners, making it one of the largest burner manufacturers and exporters in the world (see Table 2). The profit margin varied significantly across different models and different markets. Roughly speaking, larger burners enjoyed higher margins. The industrial range had an average contribution margin of about 30 per cent, the commercial range about 25 per cent, while the domestic range was less than 20 per cent. The margin in emerging markets was higher than that in developed markets. Table 2: Gino Worldwide Production in 1999 (in thousands of units) Range Output Range (kcal/hour) Domestic Commercial Industrial Total 50,000-300,000 300,000-2,000,000 >2,000,000 Gino Production in 1999 329 49 3 381 Gino Beijing Office Gino officially set up its Beijing office in 1995. The functions performed by the Beijing office included: marketing research and marketing campaigns; administration of distribution channels; technical support and counseling; key account and OEM business development; and identifying partners, in order to develop long-term co-operation initiatives, such as joint ventures. Its competitors regarded Gino as an aggressive company in marketing with an enviable budget. The marketing manager, David Zhou, was in charge of overall marketing issues, including channel management. He supervised three assistant marketing managers, each in charge of marketing-related issues in one segment. Technical manager Peter Wang was in charge of overall technical support to distributors and customers and was highly respected in China’s burner market for his ability to solve tough technical problems. He was assisted by two technical support engineers whose major responsibility was to provide field technical training to customers and distributors. The technical team was regarded as valuable to distributors and customers, particularly for new industrial and commercial applications. Page 4 9B02A013 Zhou reported to Jean-Michelle Pierre, Gino’s Asia Pacific manager, who worked in the corporate headquarters in Paris. Pierre visited the Beijing office once every two or three months, each time staying for a number of days. Zhou managed the daily marketing issues and operational issues. Managers’ financial incentives in Gino Burner Division (including Pierre, Zhou and his assistant marketing managers) were typically in the form of a bonus for achieving a unit sales quota. In the Beijing office, if the annual sales budget was met, a bonus equivalent to two months of salary (roughly in the range of RMB8,000 to RMB10,0001 per month for an experienced sales or service engineer) was granted; otherwise, no bonus was paid. Additional staff expenses, such as benefits, overtime and travel, cost Gino twice as much as salary expenses. Total compensation and expenses for a Gino engineer in China was easily three times the comparable figures for an engineer in a Chinese company. THE BURNER MARKET IN CHINA Prior to 1990 China was rich in coal resources and had been relying heavily on coal as its major source of energy. In 1990, coal accounted for 80 per cent of total energy consumption. Although coal was abundant and cheap to obtain, it was low in efficiency and high in emission of pollutants. The boilers used at this period were mostly coal-combustion boilers, which had no need for burners. 1990-1995 During the early 1990s, the Chinese government began to place more emphasis on pollution control. Some laws and regulations were passed in an effort to limit the pollution. Coal-combustion boilers, numbering in the millions in China, began to be replaced by oil-combustion boilers. Some of the world’s major burner manufacturers began to enter the Chinese market and gradually they became established brands, such as Weishaupt (Germany), Baltur and Riello (Italy), Elco (Germany), Quenod (France) and Corona (Japan). 1995-1998 A surge in applications of burners occurred during the late 1990s. Several new applications for burners emerged: absorption chillers, car painting booths, ovens and furnaces for light industries, such as tobacco processing and shoe manufacturing. The market for domestic hot water boilers was still growing, though at a slower pace, but the demand for the commercial range began to increase. More burner manufacturers entered the Chinese market. The competition moved more and more to a price basis, and burners, especially in the domestic range, became near-commodities. Chinese local factories began to manufacture small burners. For the most part, these were low-end burners, which sold only in the local community, where the manufacturer had strong connections politically. Annual local production amounted to no more than 5,000 pieces in total. Due to the lack of economies of scale, the local products were not necessarily lower in price than the imported burners. Industry experts estimated that it would 1 RMB8.3 – US$1 in 2000. Page 5 9B02A013 take local burner manufacturers at least five years to pose a material threat to the international manufacturers. Gino had gained significant penetration in the domestic range market. It became the price leader in that range,2 and its market share surged to nearly 14 per cent from less than one per cent in terms of unit volume. The growth in the commercial range, where Gino’s price advantage was less obvious, was impressive as well. Its market share also increased to nearly eight per cent from virtually zero. Gino’s performance in the industrial range, which was dominated by Weishaupt, was very disappointing. Despite offering prices 10 per cent to 20 per cent lower than Weishaupt, Gino claimed a market share of less than three per cent. Post-1999 Growth in the domestic range market was modest at best, and price competition was fiercer than ever. The commercial range became the mainstream market and the demand for large industrial burners with an output more than 2,000,000 kcal/hr was estimated to grow at more than 20 per cent per year for at least the next five years. Customer Buying Process Different burner manufacturers adopted different sales strategies to access the market. Most burner manufacturers, however, relied solely on distributors for sales. These burner manufacturers typically set up a marketing office in China (usually in Beijing, Shanghai or Guangzhou), to launch marketing campaigns, provide technical support and manage distribution channels. Weishaupt was the only burner manufacturer that had its own direct sales force and a distributor channel as well. Exhibit 1 shows the movement of burners through channels to the end users. Burners sold through distributors were first delivered from the manufacturer to its distributors’ warehouses. The distributors then had three options: sell to second-tier value-added dealers, sell to OEM customers (such as boiler factories or car painting booth makers where burners were core components of their products) or sell direct to the end users. Although OEMs or end users sometimes tried to bypass the distributors to buy burners directly from the producer, burner manufacturers usually refrained from giving quotations on direct sales, and referred these requests to distributors. Zhou explained: Distributors are very sensitive to any signal of a manufacturer’s moving to sell direct to OEM customers. They know that manufacturers always want more control over customers, and more often than not, manufacturers don’t fully trust distributors. But on the other hand, manufacturers are very cautious about alienating their distributors, because losing a distributor would make it very difficult for them to achieve their annual sales targets. Service and spare parts could be another major concern for manufacturers considering selling direct to OEMs. Who would do the service and how would spares be provided to OEMs? Pricing was also a tough issue in going direct to OEMs. In any case, the prices had to be higher than prices charged to distributors, but should they be five per cent 2 Gino’s prices were the lowest of any of the major manufacturers and competitors set their prices in reference to Gino’s prices. Page 6 9B02A013 higher, 10 per cent higher, or what? What are the appropriate criteria for these pricing decisions? The buying process for OEM customers differed from that of end users. OEM customers usually made their purchasing decisions relatively independently, whereas the decision making process of end user customers (especially if they were in the public sector) normally involved more stakeholders. For an OEM customer, “word of mouth” was very important in deciding which brand of burner to buy. In 80 per cent of cases, the first step for an OEM customer in buying a brand of burners was to pay “scouting” or “intelligence” visits to other OEMs who used the brand they were considering. In some cases, they would also approach the design institutes that usually provided systems engineering, design and consulting services for OEM products such as boilers and furnaces. Then, based on the comments from the existing customers and on the frequency of a certain brand of burner they had seen, they would contact the burner manufacturers or their distributors/dealers for preliminary quotations. Using the criteria of price, reputation, service, spare supply, reliability, technical compatibility, personal connections, etc., the OEM customer would focus on one or two candidates and then further screen by examining commercial and technical issues. As a final step, they would use various channels, including guanxi (Chinese for connections) to survey the prices paid by other burner uses. Usually, the importance of price in the buying decision was in inverse proportion to the output capacity of burners, while the importance of brand image and reputation were positively correlated with output capacity. For the domestic range of burners, price was by far the most important consideration. In the commercial range, the price was still important, but buyers paid equal, if not greater attention to technical compatibility and reliability. Supply of spares, price, and after-sales service were also considerations in making purchasing decisions. For industrial burners, reliability (as indicated by reputation and service) was more important than price. Availability of stock was another important consideration in this segment. While word-of-mouth and scouting trips were still important, design institutes played more important roles. Due to the intensified competition, the OEM customers had recently begun to pay more attention to price. End user customers usually purchased the machinery components for a project separately. For example, they bought burners from burner manufacturers and boilers from boiler manufacturers and assembled the components themselves, in order to negotiate the best possible prices and terms with each supplier. The most common type of end user customer was a government project that involved industrial burners. The project team was usually composed of end users, funding organizations, government planning commission committees, designing institutes, etc. Public tendering was most frequently used in selecting the vendors for these projects. A bidding evaluation committee, representing different stakeholders, was usually charged with the undertaking. In such cases, price and references were the most important considerations. In the past two years, there had been more tendering projects involving industrial burners than ever before. Segmentation There was no universally accepted manner of burner market segmentation in China, and no official statistics on the size of the market. The norm in the industry, however, was to divide the market into three segments: domestic boilers and hot water boilers; commercial boilers and non-boiler applications, such as dryers or incinerators; and industrial boilers. Page 7 9B02A013 Domestic Boilers and Water Heaters It was estimated that there were approximately 310 major boiler and water heater manufacturers in China in 1999. This segment began to mushroom in the early 1990s and reached its peak between 1997 and 1998. The volume of these factories ranged from 50 units to 1,500 units per annum with an average of 250 units. Almost all the boilers were matched with imported burners. Given an average price 3of RMB2,500 per unit, the market size of this segment was roughly RMB194 million. Commercial Boilers and Other Industrial Applications These applications included commercial boilers, dryers, incinerators, ovens, hot air blowers, kilns, ovens, direct combustion air conditioners and freezers. The estimated volume was roughly 22,000 units in 1999. Given the average price of RMB9,000, the market size was approximately RMB198 million. Industrial Boilers Approximately 60 manufacturers in China produced about 3,400 industrial boilers in 1999. Due to the relatively higher upfront investment in capital assets and technology, almost all these boilers were equipped with imported burners. With an average price of RMB65,000, the size of segment for imported burners was about RMB221 million. A few players, mainly European brands, dominated this segment. Weishaupt was the leading brand by a wide margin in all parts of China, especially in the south. The Range System To convert the market segment to the “range” system of Gino, Zhou and the distributors estimated the size of each range in 1999 (see Table 3). Table 3: Estimated Sizes of Ranges in Numbers of Units Sold 3 Range Market Size Domestic Commercial Industrial Total 79,900 20,080 2,920 102,900 These prices are manufacturers’ transfer prices to distributors. Page 8 9B02A013 GINO’S DISTRIBUTION NETWORK IN CHINA Organizational structure After setting up its own marketing office in Beijing in 1995, Gino enlisted three new distributors in China: Wayip Trading Co., based in the south China city Guangzhou; FUNG’s Co., based in the central coastal city Shanghai and Jinghua Mechanical Engineering Company, based in the northern city, the capital of China, Beijing. Distributors carried only Gino burners and spares. The revenue split between burners and spares was roughly 80/20. Besides handling Gino’s burner business, Jinghua also made and sold boilers. Although the profit margin on boilers was far less than that on burners, both products produced about the same revenue. The main product line of FUNG’s was still textile machinery, which accounted for over 90 per cent of annual turnover. The company placed great emphasis on burners, however, because the textile industry was widely regarded as a “sunset industry.” Wayip was the only company whose business was 100 per cent Gino burners, but it had been looking for other HVAC products for a long time. Each of three distributors was assigned exclusive rights to some provinces4 and signed a contract with Gino stating that selling burners in other distributors’ territories was strictly prohibited. Distributors negotiated annual sales budgets with Gino for a specified number of burners to be sold in the next calendar year. Distributors fulfilling the budget would be awarded a bonus of one per cent of order value (see Table 4). Table 4: Distributors’ Performance Statistics In numbers of units sold — 1999 Domestic Commercial Industrial Total Jinghua FUNG’s Wayip TOTAL 4,354 876 37 5,267 3,075 433 48 3,556 3,458 568 52 4,078 10,887 1,877 137 12,901 Distributors’ Functions Gino defined three major functions of a burner distributor in China: credit, stock, and sales/service. Credit Function Once an order was placed, Gino opened a pro-forma invoice to confirm it. The distributor then opened a letter of credit (L/C) through its bank (the opening bank) to Gino’s bank (the negotiation bank). The purpose of the L/C was to eliminate the credit risk for the manufacturer, because payment was made by the 4 Some less-developed provinces were not assigned to any of the three initial distributors. When the economies of these provinces developed sufficiently to support a number of burner sales these areas would be assigned to high-achieving distributors. Page 9 9B02A013 distributor’s bank as soon as the goods were shipped. The L/C opening fee was usually borne by the buyers. Stock Function The distributors were required to make a three-month order forecast to Gino. The forecast was adjusted on a monthly basis. The final actual order amount was supposed to vary by no more than 10 per cent from the forecast. Experience was very important in making an accurate forecast. Distributors were able to forecast much more accurately for domestic and commercial burners than for the industrial burners. “It’s a numbers game, and the learning curve matters,” as Philip Lam, the owner of Wayip, put it. The typical order cycle time was about 40 to 45 days for domestic and commercial burners and at least 60 days for industrial burners. Once the burners arrived in China, distributors made the arrangements for local transportation and warehouse stock. The distributors needed to anticipate the volume of backlog and the time of delivery carefully, in order to avoid either stock-outs or over-stocking, which resulted in tied-up capital. In most cases, the distributors would rather err on the side of caution because a stock-out would push its customer to the competitors — in many cases, once and for all. Although there were over 50 models carried by Gino, the 80/20 law applied here: about 10 major models accounted for over 80 per cent of orders. Distributors were also expected to keep sufficient stock of burner spares. Given the wide product assortment and the unpredictability of the need for spares, however, distributors were reluctant to keep a large number of burner spares in stock (especially for burners such as the industrial burners, which had a small customer base). Zhou had once been asked by Pierre about the possibility of setting up a Gino warehouse in Shanghai. He estimated the upfront investment would be roughly RMB200,000 with a monthly operation cost of RMB30,000 for a bonded warehouse holding roughly 1200 units of burners (inventory value of approximately RMB5 million). Sales and Service Function Distributors performed the customer interface function. The technical force of Gino’s Beijing office handled customer and distributor training, but only rarely did they carry out daily field service. Although some distributors used second-tier dealers to perform the sales role, most sales were made by the distributors’ sales forces. According to the contract between Gino and its distributors, the distributors were in charge of providing after-sales service, including installing and starting up commercial and industrial burners for customers. Service was usually free of charge, regardless of how long the burners had been used, but customers had to pay for spare burners once the warranty (usually one year) had expired. Gino’s gross margin on spares was approximately 20 per cent higher than that on burners across all models. In 1999, revenue from spares averaged 25 per cent of distributors’ revenue from burners. Pricing There were primarily four levels of price: transfer price (in U.S. dollars), base price (in RMB), public-listed price (in RMB) and actual contract price or transaction price (in RMB). Page 10 9B02A013 Transfer price (US$) This was the free on board (FOB) price in U.S. dollars that Gino quoted to the distributors. Gino quoted prices for all models of burners at the beginning of the year through a confidential blue book, known as “Distributor Prices.” The prices for all distributors were the same in a specific fiscal year — regardless of the volume. Prices were reviewed annually with adjustments made on all models, based on the inflation rate for the past year. Base Price (RMB) This was, in reality, the total acquisition cost to distributors in order to have full ownership of a burner, and to have it in stock and ready for sale. The distributors would pay the import duty, value-added tax, shipping and insurance and domestic transportation. The distributors’ price was then converted to base price in local currency RMB by multiplying a conversion factor of 12.32.5 Thus a burner with a US$100 transfer price would cost the distributor RMB1,232 to acquire. Public Price (RMB) At the beginning of every year, Gino released a public customer price on the market as the “guidelines for price.” The prices were in local currency and were a result of “grossing up” the base price by 60 per cent for all models. The public price in local currency of a burner with a transfer price of US$100 and RMB price of RMB1,232 then became roughly RMB1,972. Contract price (RMB) The contract price was the actual transaction price that a distributor reached in a transaction with its customer. Typically, the distributors would give customers a 20 per cent discount off the public (list) price. In the early days, there was a consensus between Gino and distributors to keep the discount from the public price to a maximum of 25 per cent. There was a tendency, however, for distributors to agree to a discount higher than 25 per cent in order to win an order. The more severe competition (particularly in domestic burners), plus the increased frequency of distributors selling outside their own territories, was contributing to the lowered contract prices. For example, a burner with a transfer price of US$100 would have a base price of RMB1,232. The figure was then grossed up by 60 per cent to get a public listed price of RMB1,972. If a distributor gave a 20 per cent discount to the customer, the actual transaction price would be RMB1,578. This would give the distributor a gross profit of RMB346. 5 The multiple of the exchange rate (RMB8.3 = US$1) x 1.484. The latter figure accounts for the cumulative effect of charges for shipping and insurance (5%), import duty (15%), value-added tax (17%), domestic transportation (3%) and miscellaneous and handling fee (2%). Page 11 9B02A013 EMERGING ISSUES Change in Strategy Gino had begun to diversify in 1998, in both product line and geographic coverage. As described by Picher, director of Gino’s Commercial Department: The strong position of Gino’s domestic range is almost unshakable. And, we are doing better and better in the commercial range. The next thing for us to do is to become a leader in the industrial range, the most robust and vigorous market. Not everyone is qualified to play in that market, but Gino has all the resources needed to succeed there — people, brand, technology, channel, etc. That’s where the largest chunk of profit in burners will be. We have been investing heavily in R&D on new industrial models. Now it’s time for harvest. It’s too bad we put almost all our eggs in one basket, the European market. I can’t imagine what will happen to us if the European market stops growing. We need to go somewhere else. But the U.S. market is hard to penetrate because Becket is so strong there. Asia looks good and China is absolutely a rising star. To deliver on its commitment for the corporate strategy, Gino China was assigned the following goals for the next three years: 1. Achieve annual combined sales volume (for all type of burners) of 15,000 units 2. Achieve annual sales of industrial burners of over 200 units 3. Optimize the distribution channels, including developing more distributors to cover the areas currently not serviced and giving distributors more marketing and technical support. 4. Develop a minimum of two OEM accounts and two end user key accounts within two years. 5. Improve service and spare supply 6. Build the brand image Distributor Behavior In recent months, there had been some marked changes in distributors’ behavior and their attitudes toward Gino. Zhou was facing the same difficult problems more and more frequently. Demand for Better Terms The distributors began to bargain more and more fiercely for better prices and lower quotas. As well, they were demanding more marketing support, such as commercial promotion and price promotion, which were usually provided only in extreme cases. Stolen Sales There were more complaints from distributors that other Gino distributors were “poaching” sales from them. The price discounts in these cases were usually much higher than the agreed maximum level of 25 Page 12 9B02A013 per cent. Besides a disgruntled home territory distributor, the other unfortunate consequence was the lack of service and technical support to the new customers. Reluctance to Stock Industrial Burners Due to the high cost of industrial burners and the difficulty in forecasting demand accurately, distributors were reluctant to keep inventories of industrial burners. What frustrated Zhou most was that the distributors were missing major “windows of opportunity.” Some industrial boiler manufacturers, who were Weishaupt customers, placed contingent orders with Gino, usually in cases of stockouts on Weishaupt burners. Gino distributors, however, were not able to take advantage of these opportunities for penetrating Weishaupt accounts because they didn’t carry inventory of the appropriate Gino industrial burner. Zhou estimated that sales of at least 50 units were lost last year, and the additional opportunity cost was difficult to estimate. Zhou was sensed that Gino was becoming more and more the hostage of its distributors. He described his feeling: The relationship is subtle. In appearance, Gino is the principal and they work for us, but in reality, they bare their teeth at Gino more and more. Sometimes, I almost lose my temper. But if I challenge them, I may immediately push them away and we will lose a big chunk of revenue. Our competitors would be happy to see that happen. But if I turn a deaf ear and keep silent, things may get worse and worse. Furthermore, there were no ideal candidates for new or replacement distributors in current view. In terms of size, only Weishaupt distributors were financially strong enough to carry the volume of Gino burners, but it appeared that they were all satisfied with Weishaupt and there were no signs that any of them wanted to defect. CURRENT PROBLEM Feima Boiler Co. Ltd. Feima was a leading boiler manufacturer in northern China, typical of the twenty largest OEMs in China (seven in southern China, seven on the east coast and six in the north). The company made over 1,200 sets of boilers of various sizes in 1999 (see Table 5). In 1999, Feima bought from Jinghua 350 sets of domestic burners, 50 sets of commercial burners and three sets of industrial burners. The rest were purchased from Gino’s competitors, such as Weishaupt (its main supplier) and Baltur. Jinghua currently allowed Feima an average 25 per cent discount off the public list price. Feima was very typical among the existing 10 OEMs that Gino had penetrated. Jinghua had been placing much emphasis on Feima and designated a sales/service engineer out of its sales/service team of nine specifically for this account. Page 13 9B02A013 Table 5: Feima’s Boiler Production in 1999 (in Numbers of Sets) Range Volume Domestic Commercial Industrial Total 1,055 163 71 1,289 The primary purpose for Feima approaching Gino for OEM treatment was to obtain better prices. It wanted at least a 10 per cent greater discount from Gino. In return, it promised to purchase at least 50 per cent of its commercial and industrial burners and all its domestic burners from Gino. Zhou liked this idea for several reasons: 1. Developing OEM business was one way to combat the increasing bargaining power of distributors. Gino had no OEM accounts prior to Feima. 2. It was a very good opportunity to break into a well-entrenched customer (Weishaupt) in industrial burners, and receive a good reference account, as well. 3. Feima had told Zhou that it would not increase the purchase of Gino burners unless it received OEM status. In other words, Jinghua was not likely to increase its sales to the company under the current status quo. 4. Gino had no OEM business in China yet. Success with Feima would make it easier for Gino to develop OEM business in other distributors’ territories. But Jinghua was adamantly opposed, for two reasons: 1. It strongly believed that Gino should not develop distributors’ existing customers as OEM accounts. 2. The practice would set a very bad example, which could destroy their confidence in co-operating with Gino. Zhou knew Jinghua was lobbying Gino’s other two distributors to back up Jinghua’s stand, because he had recently received calls from both FUNG’s and Wayip asking whether Gino would also develop “similar OEM customers as Feima” in their territories. Gong was an expert in networking, and he knew when it was in his best interest to forge an alliance. Given these circumstances, Zhou felt that it was almost impossible to over emphasize the importance of this situation. It appeared to Zhou that he was touching a landmine. DECISION Zhou had to decide whether he wanted Feima’s OEM business or not. He didn’t believe Jinghua would really leave Gino, but on the other hand, he also knew Gong was famous for honoring what he said. Zhou had to consider several aspects of the overall situation in order to come to a solution: 1. The possible response from Gino’s other two distributors 2. The message that his decision would send to competitors 3. The attitude of Gino’s corporate management once the issue was put forward in April with Picher, the director of the Commercial Department. Page 14 9B02A013 4. Feima’s response 5. Were there any other solutions that could save face for both sides? Last but not least, was Pierre willing to take the risk of losing Jinghua, which was accounting for 40 per cent of Gino’s China revenue? Was achieving control over the distributors the best objective in this case? Zhou took out the distribution contract between Gino and its distributors. It made clear in black and white that “the principal has the right to develop OEM business in the territory of a designated distributor without getting consent from the distributor.” Theoretically speaking, that was the case, but in reality, the situation might be different. Zhou knew he needed to give this matter deep thought, but he was well aware that he had very little time to make a choice and take action. The Richard Ivey School of Business gratefully acknowledges the generous support of The Richard and Jean Ivey Fund in the development of this case as part of the RICHARD AND JEAN IVEY FUND ASIAN CASE SERIES. Page 15 9B02A013 Exhibit 1 BURNER CHANNELS IN CHINA 5% 3% Burner Manufacturers Distributors 95% 100% • Gino • Weishaupt • Baltur • Reillo • Elco • Quenod • Corona 2% 15% • Jinghua • FUNG’s • Wayip 75% Dealers 12% OEMs End-users (e.g. boiler makers etc.) (e.g. District heating center) 89% 100% • Feima 3% Note: Percentages are based on the numbers of burners sold through a particular channel (i.e. on volume, not value).