Uploaded by

shaheer makar

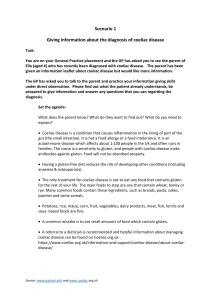

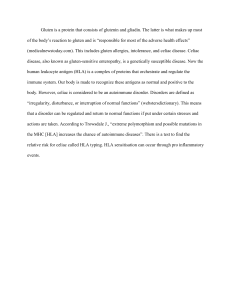

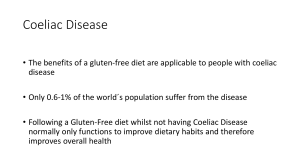

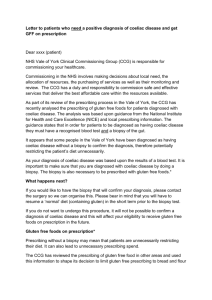

Coeliac Disease: BSG Adult Diagnosis & Management Guidelines

advertisement