ACL Reconstruction Rehab Protocol: Hamstring Autograft/Allograft

advertisement

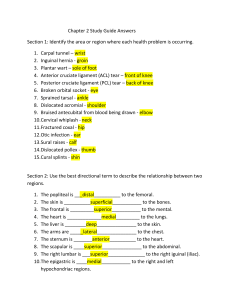

Dr James Coulthard Rehabilita*on Protocol for Anterior Cruciate Reconstruc*on with Hamstring autogra9 or allogra9 The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is an important structure providing sagi9al plane and rotatory stability to the knee. Loss of ACL func?on will adversely affect ?biofemoral contact forces in the knee, and knee stability. This can lead to progressive damage to the joint either through macro or microtrauma. Reconstruc?ve surgery aims to restore knee stability, and protect the knee from further injury. Longterm observa?onal studies of delayed reconstruc?on have shown delayed surgery may be associated with a significantly greater rate of damage to the meniscus, the ar?cular car?lage or both (Frobell, et. al. 2010). Data from Brambilla’s (2015) retrospec?ve cohort study shows, how medial meniscal tear prevalence increases, especially aOer 12 months in non-reconstructed knees. They concluded that for each month of delay of ACLR, increased the risk of intra-ar?cular damage by 0.6%. Poten?al problems following surgery include infec?on, graO rupture, arthrofibrosis, knee s?ffness, ongoing swelling, DVT, cosme?c issues and the various risks with general anesthesia. The decision whether to reconstruct is a complex one determined by weighing up the risks and benefits, as well as considering if the pa?ent is prepared to par?cipate in an intensive rehabilita?on for approximately 12 months. Rehabilita?on can be challenging. Twenty to thirty individual physiotherapy consulta?ons, and over 200 hours of rehabilita?on may be required, par?cularly for athletes wan?ng to return to pre-injury status. Not all reconstructed knee return to pre-injury ac?vity. Pa?ents oOen expect full return to pre-injury func?on, but this is unrealis?c for many. To summarise some of the literature: • 42 - 65% of all pa?ents return to pre-injury sport (Wellsandt, Failla, Axe & SnyderMackler, 2018, Ardern, Taylor, Feller & Webster, 2014) • 83% of elite athletes return to pre-injury sport (Lai, Ardern, Feller & Webster, 2017) • 22 - 30% have a second ACL injury on Return to Sport ((Mar?n et al., 2022, Paterno, Rauh, Schmi9, Ford & Hewe9, 2014) Delaying return to sport to at least 9 months and restoring normal muscle strength results in lower re-injury rates. (Grindem et al., 2014) This protocol aims to provide a general guide for post-opera?ve management of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruc?on. It is wri9en for health care professionals, primarily Physiotherapists and is not intended to be distributed to pa?ents. Varia?ons in the protocol may be specified depending on other procedures performed such as meniscal repair, meniscectomy, anterolateral ligament augmenta?on, and other pa?ent specific and surgery specific factors. This is a guide only, and therapist will have to s?ll make their own clinical decisions based on factors such as available equipment, pre-injury requirements, and individual pa?ent progress. It is a conserva?ve protocol and assumes up to 12 months to return to high level ac?vity. This protocol applies to hamstring autograOs and allograOs. Notes have been included with this protocol and are important. Stage 1 Recovery from Surgery – Weeks 1 and 2. Aims: - Manage post opera?ve pain/swelling Minimise muscle inhibi?on and reac?vate quadriceps Start regaining range of mo?on Maintain patellofemoral mobility Gradually improve walking and weightbearing Criteria for progression to stage 2 - Full or nearly full passive knee extension Knee flexion to 100 degrees Straight leg raise without lag Swelling 0 – 1+ Stage 2 Strength and Neuromuscular Control - 3 – 6 weeks. Aims: - Further reduce post opera?ve pain/swelling Quadriceps and glute strengthening Maintain patellofemoral mobility Normal walking and weightbearing Criteria for progression to stage 3 - Nearly full flexion (within 10 degrees of other leg) Full extension Swelling 0 -1+ Stage 3 – Strength and Neuromuscular Control - 7 – 12 Weeks. Aims: - Con?nue strength and condi?oning and gradually add hamstring strengthening Maintain full knee range of mo?on Criteria for progression to stage 4 - Quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes test to >80% with dynamometry Normal sit to stand Single leg squat to 90 degrees Symmetrical star excursion with good control No instability symptoms No swelling Stage 4 - 13 Strength and Func2onal Recovery 13 – 26 weeks. Aims: - Progress strengthening - Introduce early sports specific drills Introduce func?onal, neuromuscular and balance exercises including o Teach correct landing mechanics o Low intensity straight line running o Hopping exercises Criteria to progress to Stage 5 – 6 months+ aOer surgery - Quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes test to >90% with dynamometry Hamstring: quadriceps ra?o >70% Normal straight line running gait Normal triple hop test Normal balance Stage 5 – Progressive return to Full Func2on - 6-12 Months following surgery. Aims: - Progress strengthening Normalise sports specific movements Return to full sport Criteria to progress to full return to full ac?vity - Normal clinical examina?on 100% strength and endurance Normal Lachman’s and Pivot shiO Normal landing mechanics if required Normal Hop test ba9ery (hop for distance, ver?cal hop, side hop) Pre-injury running gait and speed restored if required Normal func?onal tes?ng in a fa?gued and non-fa?gued state Normal general fitness Normal psychological state and confidence (ACL RSI) Minimum 9 months since surgery Stage 6 - Preventa2ve Programming. There are several ACL injury preven?on programs which aim to maintain or improve neuromuscular control during func?onal tasks. These include • • • • • Sportsmetrics Program The FIFA 11+ Warm Up The PEP Program • The KNEE Program - Netball Australia • The FootyFirst Program - AFL Appendix: Descrip2on of test measures Knee range of mo2on. This is measured using a long-arm goniometer. Bony landmarks: greater trochanter, lateral femoral condyle, and lateral malleolus. Swelling grades. Using stroke test: Zero: no wave produced on downstroke Trace: small wave on medial side on downstroke 1+: Large bulge on medial side on downstroke 2+: Effusion spontaneously returns to medial side aOer upstroke 3+: So much fluid it is impossible to move effusion out of the medial aspect of the knee Hop test ba9ery. There are numerous versions of hop test. These are most relevant in the return to sport seong, and performing several of these is recommended. Examples are described below. Triple Hop Test (Noyes 1991). Subjects are required to hop forwards three consecu?ve ?mes on one foot. The total distance is measured and the average of 2 valid tests is recorded. Measure from toe at takeoff to heel at landing. Arms are free to swing. A limb symmetry index is calculated by dividing the mean distance (in cm) of the involved limb by the mean distance of the non-involved limb, then mul?plying by 100. The goal is 95% compared with the other side. Side Hop Test (Gustoavsson et al,. 2006) Subjects stands on test leg with hands behind the back and jumps from side to side between two parallel strips of tape, placed 40 cm apart on the floor. Subject jumps as many ?mes as possible during 30sec. The number of successful jumps performed, without touching the tape is recorded. The goal is 95% compared with the other side. 1. Ardern, C. L., Taylor, N. F., Feller, J. A., & Webster, K. E. (2014). Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(21), 1543– 1552. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-093398 2. Brambilla, L., Pulici, L., Carimati, G., Quaglia, A., Prospero, E., Bait, C., … Volpi, P. (2015). Prevalence of Associated Lesions in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(12), 2966–2973. doi:10.1177/0363546515608483 3. Cooper, R., Hughes. M., (n.d.). Melbourne ACL rehabilitation guide 2.0. Melbourne, Vic. 4. Frobell, R. B., Roos, H. P., Roos, E. M., Roemer, F. W., Ranstam, J., & Lohmander, L. S. (2013). Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five-year outcome of randomised trial. BMJ, 346(jan24 1), f232–f232. doi:10.1136/bmj.f232 5. Gustavsson, Alexander, et al. "A test battery for evaluating hop performance in patients with an ACL injury and patients who have undergone ACL reconstruction." Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 14.8 (2006): 778788. 6. Lai, C. C. H., Ardern, C. L., Feller, J. A., & Webster, K. E. (2017). Eighty-three per cent of elite athletes return to preinjury sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review with meta-analysis of return to sport rates, graft rupture rates and performance outcomes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(2), 128–138. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096836 7. Martin, R. K., Wastvedt, S., Pareek, A., Persson, A., Visnes, H., Fenstad, A. M., … Engebretsen, L. (2022). Predicting subjective failure of ACL reconstruction: a machine learning analysis of the Norwegian Knee Ligament Register and patient reported outcomes. Journal of ISAKOS, 7(3), 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jisako.2021.12.005 8. Noyes, Frank R., et al. "A training program to improve neuromuscular and performance indices in female high school basketball players." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 26.3 (2012): 709-719 9. Noehren, B., & Snyder-Mackler, L. (2020). Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? Open-Chain Exercises After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 50(9), 473–475. doi:10.2519/jospt.2020.0609 10. Paterno, M. V., Rauh, M. J., Schmitt, L. C., Ford, K. R., & Hewett, T. E. (2012). Incidence of contralateral and ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury after primary ACL reconstruction and return to sport. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 22(2), 116–121. doi:10.1097/jsm.0b013e318246ef9e 11. Wellsandt, E., Failla, M. J., Axe, M. J., & Snyder-Mackler, L. (2018). Does Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Improve Functional and Radiographic Outcomes Over Nonoperative Management 5 Years After Injury? The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(9), 2103–2112. doi:10.1177/0363546518782698 ACL RECONSTRUCTION WITH AUTOLOGOUS HTG To the end of week no tubigrip due to risk of DVT. ROM approximate goals: 0-100° note 1 0-125° 0-full° Weight-bearing: 25 - 75% body weight. Note 2 75 - 100% body weight. Note 2 Patella Mobilisation: Note 3 Modalities: Electromuscular stimulation. Note 4 Pain/oedema Management (cryotherapy) Stretching: quadriceps, hip flexors. Note 5 hamstrings. Note 6 Gastrocnemius-soleus Strengthening: Quads isometrics, SLR, active knee extension DVT preventative exercises gait retraining, walking, and running. Notes 7,8 toe raises, mini-squats, TRX assisted squats Knee flexion hamstring curls, bridging Knee extension quadriceps (0 - 90) Hip abduction-adduction, extension. Note 9 Leg press (70°- 0°) leg press (0 - 100) full squat or full leg press Balance/proprioceptive training: Weight-shifting, single leg balance Y-excursion balance, perturbation, neuromuscular Conditioning: arm ergo, bike, rowing, aquatics, elliptical Elliptical machine core strengthening Running straight: note 12 Cutting, carioca, figure-eights, hopping. Note 10 Plyometric training. Note 10 Full sports. Note 11 2 4 6 8 12 16 20 26 30 34 40 x x x 52 X x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x X X x x x x x x x x x 1. If a pa?ent has persistent flexion contracture a zimmer can be worn at night for a few weeks. Aim to achieve full extension by 1-2 weeks. 2. Crutches and or a zimmer splint are some?mes recommended un?l gait is safe, and full knee extension has been achieved, and a consistent, comfortable, locked straight leg raise can be demonstrated 3. Patella mobilisa?ons can be con?nued for longer if there is persistent loss of patellar mobility. 4. Very li9le evidence but probably a dose response rela?onship. 3 x 20 min/per day 5. Quads stretches only possible with near full knee flex range of movement 6. Hamstring stretches are very gentle in the early phase and are used to minimise adhesions 7. Start running retraining. Lower limb strength should be at 95% or above, full knee ROM, 95% on Y-excursion and minimal knee effusion. 95% Lyshom knee score 8. Emphasise full knee extension at heel strike. 9. Gluteus maximus is an important external rotator of the hip. Deficits may predispose to injuries 10. Commence plyometrics and mul? direc?onal movements only when back to full strength, full y excursion and no knee effusion. 95% Lyshom knee score 11. Full strength, ROM, 100% Lyshom knee score, 100% Y-excursion c.f. to other limb, 100% single hop and 3 hop tests, full cardiovascular fitness, on field, sports specific drills, Good performance on drop ver?cal jump (no valgus, > 72 degrees knee flexion (Hewi9 2005), no excessive trunk sway) 12. Commence running when full strength and no effusion