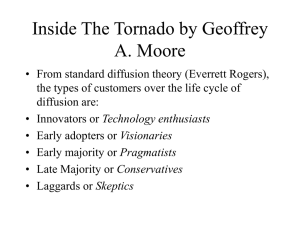

Inside the Tornado: Marketing Strategies from Silicon Valley

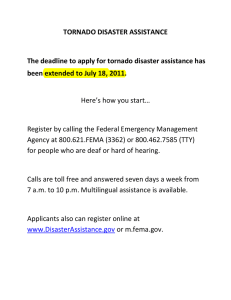

advertisement