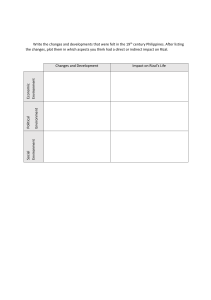

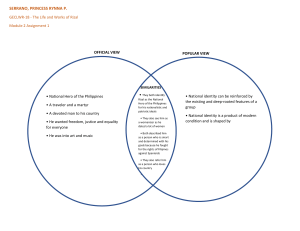

How Did Rizal Became Who He Was? Have you ever wondered what makes you, you? Our personalities are shaped not only by genetics, but also by a multitude of experiences and events that are interwoven throughout our lives.¹ It's like a puzzle, with different factors coming together to create the bigger picture. Some of these factors are within our control, while others are beyond our hands. Rizal was born in the 19th century, a time marked by significant changes in the world. He grew up amidst the Philippines' struggle for independence and the shifting social, economic, cultural, and political landscape of the time. These changes played a role in shaping his perspective in life. To better understand how Rizal became who he was, let's take a closer look at what was happening in the 19th century. THE 19TH CENTURY The 19th Century marked a significant shift towards modernity,² which entailed a break from traditional ways of life and the emergence of new ideas, attitudes, and institutions. It was also part of the Age of Revolution, as it was characterized by several transformative events, including:³ 1. 2. Industrial Revolution: The industrial revolution brought about new modes of production, transportation, and communication, leading to a shift from manual labor to machine-based production.⁴ This transformation of the economy and society resulted in new forms of work and leisure, as well as urbanization and the growth of cities.⁵ Political Revolutions: Various political revolutions occurred during the 19th and late 18th century, such as the American Revolution and the French Revolution. These political upheavals were heavily influenced by the Enlightenment,⁶ a philosophical movement that valued reason, rationality, and individualism. The wave of political change challenged the power of the monarchy and paved the way for new forms of governance based on individual rights, nationalism, and freedom.⁷ ECONOMIC CONDITION I: END OF GALLEON TRADE Whilst different parts of Europe were flourishing, such as Britain due to the Industrial Revolution and France due to the French Revolution, Spain was experiencing a slow decline.⁸ To better understand why, we need to examine its economic condition during this period. Trading in the Philippines can be traced back to the time before the Spanish colonization. Early Philippine merchants traded with various countries, such as China, Japan, Siam, Cambodia, India, Borneo, and the Moluccas. When the Spanish Crown arrived, they saw an opportunity to profit from this trade. They closed the ports of Manila to all countries except Mexico, which was also a colony of Spain during the 16th century.⁹ This decision created a trade monopoly, known as the Manila-Acapulco Trade or Galleon Trade, which made Manila the center of commerce in the East.¹⁰ The goods traded included mangoes, tamarind, rice, carabao, Chinese tea, textiles, fireworks, perfume, precious stones, and tuba (a coconut wine). These were sent to Mexico and, on the return voyage, numerous and valuable flora and fauna were brought into the Philippines, including guava, avocado, papaya, pineapple, horses, and cattle.¹¹ The trade monopoly made Spain a mercantilist superpower for a while. However, it did not last forever.¹² The decline of the Galleon Trade can be attributed to several factors. These factors include: Tough competition from other nations who became self-sufficient and preferred direct trade, leading to the decline of Spain's trading system and demand for Asian goods.¹³ Spain's heavy dependence on the silver mines of its colonies in South America, which slowly dwindled over time. This decline in silver production led to the devaluation of silver and reduced the profit margins of Galleon Trade merchants.¹⁴ Revolts in the New World, particularly the War for Independence in Mexico, shifted the focus and priority of consumers away from trade. As a result of these factors, the Galleon Trade was no longer sustainable. By the first decade of the 19th century, the trade system was ended by decree. ECONOMIC CONDITION II: COMMERCIAL PURPOSE Because the Galleon Trade ended, the Philippines needed a new commercial purpose.¹⁶ The economic opportunities created by the Industrial Revolution encouraged Spain to open the Philippine economy to world commerce in 1834.¹⁷ The Philippines became a supplier of raw materials for Western industries by utilizing underutilized land resources for cash crop agriculture - a type of farming where crops are grown primarily for sale rather than personal or local consumption.¹⁸ British, Dutch, and American trading companies invested large capital in the country for the large-scale production of different products, such as tobacco and sugar. To make transactions easier, foreign investors need people who are already in the Philippines, such as Chinese, mestizos, and rich natives. They help them with the acquisition of lands, mobilization of labor, transportation of crops, and retail trade.¹⁹ Chinese immigrants served as middlemen between the provinces, where the crops were planted, and the merchant houses of the Mestizos in Manila. Rich natives became tenants, known as ‘Inquilinos' in Spanish. Inquilinos oversee the production of cash crops by subleasing large estates or haciendas from friars and then subletting them to indigenous farmers.²⁰ When the Suez Canal, an artificial sea-level waterway, was opened, the distance of travel between Europe and the Philippines was considerably shortened. The opening of the Suez Canal, construction of steel bridges, and safer and faster gave way to more intensive production of crops, which provided a huge advantage in commercial enterprises.²¹ Positive effects took place as the industrial revolution contributed many things to the people:²² 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. The Philippines was opened for world commerce. Foreigners were engaged in manufacturing and agriculture. The Philippine economy became dynamic and balanced. There was rise of new influential and wealthy Filipino middle class. People were encouraged to participate in the trade. Migration and increase in population were encouraged. As evidence of this growth, the total trade of the Philippines increased from 2.8 million pesos in 1825 to 31.1 million pesos in 1875, and by 1895 it had grown to 62 million pesos.²³ ECONOMIC CONDITION III: CONNECTION TO RIZAL What does all of this have to do with Rizal? Well, the fast tempo of economic progress in the Philippines during the 19th century facilitated by Industrial Revolution resulted to the rise to a new breed of rich and influential Filipino middle class.²⁴ This made the Inquilino class wealthy, which include the Rizal patriarch, the family Mercado.²⁵ In the mid-18th century, when Rizal's Chinese ancestor Domingo Lam-co arrived at the Binan hacienda, the average holding of an Inquilino was 2.9 hectares. However, when Rizal's father moved to the Calamba hacienda, the Rizal family rented over 390 hectares from the hacienda in the 1890s.²⁶ The family Mercado became one of the most affluent family in Calamba. This enabled the family to live a prosperous and comfortable life, thus giving the Rizal children more time and focus toward education.²⁷ SOCIAL CONDITION During the early years of the Spanish colonial period (until mid-19th century), education was not a right but a privilege, usually reserved for those who belonged to the highest racial class. This class consisted of a privileged few, mostly individuals with Spanish blood, who had the opportunity to pursue college education.²⁸ To better understand this racial hierarchy, let's take a closer look at how it was structured in the Mariana Islands for administrative purposes:²⁹ 1. 2. Peninsulares - The highest class was the Peninsulares, which consisted of pure-blooded Spaniards who were born in the Iberian Peninsula, such as Spain.³⁰ They were officials and friars who had the power and authority to rule over the Filipinos. Creoles or Insulares - The second-highest racial class was the Creoles or Insulares. Insulares were the specific term given to creoles, who were full-blooded Spaniards born in the colonies, born in the Philippines or the Marianas.³¹ 3. 4. 5. Mestizos - Mestizos, or colloquially Tisoy, referred to people of mixed native Filipino and any foreign ancestry.³² Filipinos - Persons native to the Philippine Islands.³³ Indios - The lowest class was the Indios, a term that lost its original meaning as Spanish officials used it negatively to refer to the poor people of the country who were viewed as inferior and treated as second-class citizens.³⁴ Spanish blood was highly valued during the Spanish colonial era, and as Spanish blood disappeared, so did all the privileges that came with it. If you have noticed, Insulares are still full-blooded Spaniards, but just because they were born in the Philippines, they were ranked lower. This is because the Philippines was viewed negatively by Peninsulares as a "dumping ground" for societal misfits. Those with any trace of Indio blood were never considered social equals of pure-blooded Spaniards.³⁵ Filipinos were viewed as inferior, associated with backwardness, primitiveness, and inferiority. This hierarchy, likely, affected access to education, making obtaining higher/college education difficult for those at the bottom of the hierarchy. "All these institutions (Jesuit Colegio de San Jose, Dominican Colegio de Santo Tomas, Colegio de San Juan de Letran) were meant for students of Spanish blood…" "Even if one admits that in due time to natives, that is indios, were admitted to these schools, the main student population was Spanish." (Arcilla, "Philippine Education: Some Observations from History") "Before 1863, the kind of primary education provided for the natives did not go beyond the parochial catechetical level. Although there were colleges already opened to the natives who were studying for priesthood, there were, for all practical purposes, no chances for other natives to pursue higher education which was reserved mainly for Spaniards, and Spanish mestizos to some extent. Up to the 1860's, the most educated segment of the native population were the native secular priests." (Majul, "Principales, Ilustrados, Intellectuals and the Original Concept of a Filipino National Community") The spoils of the growing economy (during the latter half of 19th century) transcended race and ethnicity. Wealthy families like the Rizals were able to send their children to study in prestigious schools. For instance, the female children of the Rizals studied at La Concordia, while their son Paciano studied at Colegio San de Jose.³⁶ During a period of relative prosperity, many families were able to send their sons to Spain and Europe for higher studies.³⁷ There, these young Filipinos were exposed to secular and liberal ideas that were made possible by the French Revolution. The experience inspired them to form the Ilustrados, a group of educated natives who sought reforms. Note: In the video, I said that the Ilustrados advocated for independence. Although this is partly true, as historian Ambeth Ocampo (Inquirer, "Reform and Revolution") and writer Floro Quibuyen (PODKAS, "Rizal on Air") have stated that reform and assimilation were only seen by Rizal, del Pilar, and others as a first step towards eventual separation from Spain, and that there was no real difference between reform and revolution in the 19th century, it is perhaps more accurate to say that the Ilustrados "sought reforms," as this is the term most commonly used by historians to describe their goals. CULTURAL CONDITION The emergence of the nationalist movement in the late nineteenth century in the Philippines was influenced by several factors. Although the role of ideas learned by the European-educated Ilustrados is often emphasized, it was not just this group of Filipinos or the European intellectual atmosphere that stimulated nationalism.³⁸ One key factor was the cultural development that resulted from the rapid spread of education from about 1860. (It was only in the latter half of the 19th century that the government took an active part in promoting education in the colony.³⁹) The spread of higher education among middle and lower-middle-class Filipinos, who could not afford to go abroad, played a crucial role in propagating the liberal and progressive ideas written about from Europe by Rizal or Del Pilar.⁴⁰ To further understand the emergence of nationalism in the Philippines, it is essential to examine the educational reforms that occurred in the mid-19th century. These reforms opened up educational opportunities to a wider segment of society, helping to democratize education in the country. By 1866, the proportion of literate people in the Philippines was higher than in Spain. The proportion of Filipino children attending school was also above average in European standards. (De Guzman, Esquire Magazine Philippines) By emphasizing humanistic education and principles of justice and equality, these reforms helped to undermine the foundations of the Spanish colonial regime and inspired a growing sense of national identity among Filipinos. This growing sense of nationalism would ultimately pave the way for significant political developments, including the pursuit of greater democracy. POLITICAL CONDITION During Rizal's era, calls for democracy echoed throughout the Philippines. To understand why, we must delve into the country's past, specifically to the 16th century when Spanish missionaries introduced Christianity to the archipelago. Although the religion emphasized equality among all people, the Spanish colonial authorities did not treat brown-skinned Filipinos equally.⁴⁹ This discrepancy reflects George Orwell's famous quote from Animal Farm: "All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others." Despite this hypocrisy, most Filipinos (excluding those in the hinterland of Luzon and the Visayas, as well as in Mindanao and Sulu) embraced Christianity.⁵⁰ Over the next three centuries, Spain used religion to justify exploitative practices such as forced labor, cultural suppression, conquest, and violence. By doing so, Spain demonstrated the corrupting power of religion and the ways it can be used for oppression and exploitation. During Rizal's time, the court of justice in the Philippines was notoriously corrupt. They were a court of "injustice," as far as brown Filipinos were concerned. Spanish fiscals (prosecuting attorneys) and other court officials were often inept, venal, and ignorant of the law. As a result, brown Filipinos were frequently treated unfairly, and justice was slow, partial, and costly. The poor had little access to the courts due to the high costs of litigation, while those with white skin color or wealth were often favored in court.⁵¹ According to John Foreman, a British eyewitness to the last years of Spanish rule in the Philippines,⁵² "It was hard to get the judgment executed as it was to win the case." Even when a verdict had supposedly been reached, a flaw in the sentence could always be concocted to reopen the entire affair. Foreman further observed that if the case had been tried and judgment given under the Civil Code, a flaw could be found under the Laws of the Indies, the Siete Partidas, Roman Law, Novísima Recopilación, Antigous Fueros, Decrees, Royal Orders, or Ordenanzas del Buen Gobierno, among others, leading to the case's reopening. Racial prejudice was also widespread in the Philippines. Filipinos were not allowed to organize assemblies or political meetings, and merit was determined not by one's qualifications or abilities but rather by one's wealth, race, and connections with influential individuals. This discriminatory system created a sense of oppression and discontent among the local population. The Spanish colonial government in the Philippines was highly centralized and authoritarian. It imposed strict social and political hierarchies, denying Filipinos basic political rights and freedoms. The Church played a significant role in the state's proceedings, manipulating the indigenous people to comply with the state's laws as it saw fit. Meanwhile, the colonial government was primarily interested in exploiting the country's natural resources and labor for the benefit of Spain. In addition, the money collected from the natives was not used to improve their province, but rather for the selfbetterment of the officials. The system was exploitative and maintained through the use of force, including military forces deployed to quell uprisings and rebellions. If you witnessed such injustices happening to your fellow Filipinos, wouldn't you feel angry? That's precisely how Rizal, Ilustrados, and other Filipinos who were exposed to liberal ideas felt when they witnessed such injustices. They viewed Spanish officials and its practices as regressive, incompatible, and the main reason why the country was not progressing.⁵³ In one of Rizal’s letter, he said: "I wanted to hit the friars since the friars are always making use of religion, not only as a shield but also as a weapon, protection, citadel, fortress, armor, etc., I was therefore forced to attack their false and superstitious religion in order to combat the enemy who hid behind this religion... God must not serve as shield and protection of abuses, nor must religion."⁵⁴ Note: During the 19th century, the Philippines was under a frailocracy, or a government by friars. This meant that the distinction between church and state was blurred. The British colonial masters were overthrown to gain independence and achieve the status of becoming a sovereign nation, a feat that spread across European countries and other parts of the world. This motivated people to follow suit. Filipino reformists like Rizal were inspired by the revolution to pursue freedom and independence for the country. It's high time for these abuses to end.⁵⁵ The thirst for reform and nationalism flourished in the liberal atmosphere, and, to make a long story short, this led to the Philippine Independence movement and the death of Rizal. The cries for democracy during Rizal's time were a result of the long-standing injustices and corruption of the Spanish colonial authorities, who used religion to justify their actions. The call for democracy was a call for equality, justice, and fairness for all Filipinos, regardless of their skin color or social status. If Rizal Were Born Today… If Rizal were born today, would he still be the same Rizal that we knew? It's hard to tell. If he were born in a different period, then his experiences and ideas would also be different, which would lead him down a different path. But one could argue, has anything really changed? Oppression and inequality still persist, and Rizal was passionate about advocating for the equality of the Filipinos. So maybe if he were born today, he would still be the same person. Nonetheless, it is worth pondering how different circumstances, such as being born into a less privileged family or not having access to like-minded individuals, would have influenced the trajectory of his life. "We all make choices, but in the end, our choices make us." - Andrew Ryan (Video Game Character)