Capital Structure in Central & Eastern Europe: Managerial Perspectives

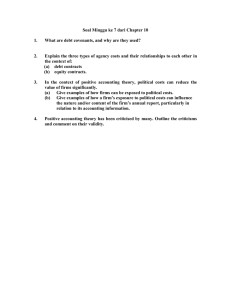

advertisement