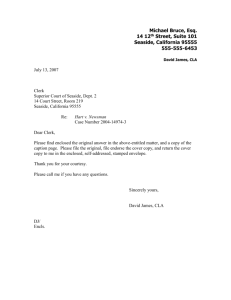

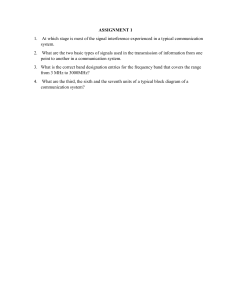

77 years later, bandleader's death continues to confound Was Jimmie Lunceford poisoned? In the 1940s, Seaside, Oregon, was witness to a curious and disturbing incident, the death of an internationally famous jazz bandleader, Jimmie Lunceford, his death coming while signing records at a store on the city’s main street. The nature of his death on July 12, 1947, whether it was a a heart attack, food poisoning or something else remain in question even 77 years later. Even eyewitnesses— the musicians in the band remembered the incident differently. One thing is clear: Lunceford’s death came at the conclusion of a racially charged visit to Oregon.Oregon didn’t repeal its Exclusion Law, which barred Blacks from the state until 1926. The next year the Oregon Constitution was amended to remove a clause denying Blacks the right to vote and eliminating restrictions that discriminated against Black and Chinese voters. The Ku Klux Klan arrived in the state in 1921. In the post-World War II years, the state’s demographics were changing. As described in “Jazz Back in the Day” from Oregon Public Broadcasting, the racial segregation that had long characterized the city, began, in modest increments, to break down. In those new North and Northeast Portland clubs — and eventually in other venues around town — customers began to sit, dine and sometimes even dance together. Seaside, 78.4 miles to the west, was unique in its role as a getaway for Portlanders and a recreational playground for the Northwest to Idaho and Utah. As an escape valve for defense workers who migrated to Portland and the Pacific Northwest during the World War II years, Seaside attracted an increasingly diverse population. More than 200,000 people flooded the Portland area during the war years, 20,000 of them Black. In the 1940s, Seaside’s Sandy Winnett worked as a waitress at the ice cream shop adjacent to the Bungalow. Winnett remembers an “open-minded attitude” among most Seaside residents, a time when people of all backgrounds “came to dance” in Seaside. It wasn’t just white bands like Glenn Miller, Les Brown and Tex Beneke that headlined Seaside’s top club, but Lionel Hampton, Cab Calloway and Fats Waller. “Dancing in those days was a much bigger social event than it is today,” said Seaside author Gloria Stiger Linkey in a 2016 interview. “We danced every Friday night at the high school. After the basketball and football games, we had a dance. We danced all the time.” Linkey remembered a time when teens would drive their cars — or their parents’ cars— to Seaside’s Cove, turn their radios on and dance through the night by the beach. ”We did have African Americans in the summer from Portland,” Linkey said. “There was an influx during World War II. They worked in the shipyards.” There was no animosity, she said. “No racism at all. At least growing up in Seaside, I didn’t feel it.” As a tourist town, the goal was to sell as many tickets as possible, she added. “Because if you can serve tourists, you can serve African Americans.” African Americans also came to Seaside and nearby Gearhart employed as domestic help for wealthy families, Seaside’s Mary Cornell, a teen at the time, recalled. ‘The King of Syncopation’ James Melvin “Jimmie” Lunceford, born June 6, 1902 in Fulton, Mississippi, moved to Denver, Colorado at the age of 15. There he studied music under the instruction of Wilberforce J. Whiteman, conductor of the Denver Symphony Orchestra. Whiteman was the father of Paul Whiteman, the world’s highest-paid dance bandleader and known to the public as the “King of Jazz.” Lunceford studied the saxophone, flute, guitar, and trombone at an early age, making his professional debut in early 1920 with the ninepiece Morrison Jazz Orchestra. Urged by his family, Lunceford left for Nashville in 1922 to enroll at Fisk University, a prestigious Black educational institution that had produced thinkers and artists like W.E.B. Dubois, scholar James Weldon Johnson, and pianist Lil Hardin, who later married Louis Armstrong. After receiving his degree from Fisk, he moved to Memphis to begin teaching music classes at Manassas High School, a school already renowned for its advanced musical curriculum and record of achievement. Lunceford recruited his brightest students for his own band, the Chicksaw Syncopators, spending summers and holidays at a resort in Lakeside, Ohio on the shores of Lake Erie. In late 1929, the group turned professional. Under Lunceford’s direction, the band launched a series of one- nighters throughout the midwest. Their big break came when they arrived in New York City and began a residency at the famed Cotton Club in Harlem. The band was known for its tight ensemble work and sophisticated arrangements rather than for individual soloists. The music is upbeat, intimate and fun. It can be silly and sentimental. The goal was getting kids onto the dance floor for a spin. The tunes were playful, sometimes gimmicky and the titles funny: “I’m Nuts About Screwy Music,” “Call the Police” and “Water Faucet Drip-Drip-Drip.” Lunceford’s 1935 “Harlem Express” tour shattered box office records — families traveled more than 100 miles to see the band; attendance less than 1,000 people per night was considered a slow night. Often it was more than 4,000, Lunceford’s biographer Eddy Determeyer wrote in “Rhythm is Our Business: Jimmie Lunceford and His Harlem Express.” The great jazz pianist Fats Waller recognized Lunceford’s genius by dubbing him “The King of Syncopation.” Although the band first started recording in 1930. they scored 22 hits between 1934 and 1946, more than any other black swing band with the exceptions of Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway. Like other big bands, Lunceford was having difficulty financing his big band in the mid-1940s. Against the tide, Lunceford rebuilt his band with studio and classically trained musicians; critics praised the ensemble’s “self-confidence” and considered it “one of the best on the scene.” July 12, 1947 It was into this environment that Lunceford and his orchestra arrived in Seaside in July 12, 1947 to play the Bungalow, the city’s preeminent dance hall. The previous night, the musicians had been hassled at a Portland restaurant, according to trumpeter Joe Wilder in Edward Berger’s “Joe Wilder and the Breaking of Barriers in American Music.” The Lunceford band had played McElroy’s Spanish Ballroom in Portland. At intermission they went into a restaurant across the street. The break was only 20 minutes, but after 40 minutes, no one came to take their order. Finally one of the musicians asked, “Can we get some service?” The owner replied, “We don’t serve you people here.” She made a phone call and “the next thing you know,” Lunceford trumpeter Joe Wilder remembered, is that four policemen descended on the restaurant. The musicians received an assist from the officers, who told the owner that according to the law, if she wouldn’t serve the men, she would have to close the restaurant. “So she walked over to the door and pulled the curtain down with a sign that said ‘closed.’ And that was it. We just didn’t eat and went back and played.” The next day, late in the afternoon after the bus ride to Seaside, the band members found more difficulty in simply ordering a meal. Lunceford band bass player Truck Parham remembered that band members walked into a restaurant on Downing, not far from the Bungalow. On scanning the group, the waitress told the musicians: “Can’t serve you. We don’t have no food.” Determeyer writes that Lunceford, normally even-tempered, even restrained, pounded the table with his fists. ”What the hell do you mean, you can’t serve us?” Lunceford demanded. “Call the manager!” The waitress panicked and hurried back to the kitchen. After a minute or two, Determeyer wrote, she came back and said the men could order after all. They ordered hamburgers. ”No, I’m sorry,” the waitress said. “We don’t have nothing but beef sandwiches, hot beef sandwiches.” Wilder remembered the menu differently — he told Determeyer that they had to “content themselves with strawberry pie.” “Most of us ate two slices of it and Jimmie did likewise,” Wilder said. “And I think he caught what I thought was indigestion.” According to Determeyer’s account, after the meal, most of the band members returned to the Bungalow before the show, except for Lunceford, who complained he was tired and wasn’t feeling well. According to Determeyer, he complained to trumpeter Russell Green he was tired and wasn’t feeling well. After a short walk on the city’s oceanside Prom, he was approached by a record store owner who asked him to sign autographs. After sitting on a bench Lunceford got up and told Green, “I’ll be all right, I gotta go across the street here and autograph some records at this record place.” Trumpeter Wilder said that Lunceford took some BC tablets — aspirin — after complaining of a severe headache. “He took a double dose,” Wilder said. Lunceford headed to Seaside Radio and Record Shop at 411 Broadway in the Strand Theatre building— sometimes called “Callahan’s,” after its owner Mike Callahan — accompanied by Wilder and trombonist Al Cobbs. According to the report in the weekly newspaper the Seaside Signal, Lunceford was about to autograph a wall reserved for names of musical celebrities who came to Seaside, when operators Edward and Walter Hill noticed Lunceford looking weak and ill. A moment later the bandleader collapsed and was seized by severe convulsions. Lunceford was autographing albums when suddenly he spun around and keeled over and fell, Wilder said. The Hills called the police and an ambulance arrive a little later, but Lunceford died before the ambulance reached the Seaside hospital half-a-mile away. He was 45 years old. Meanwhile, before the gig, the band knew nothing about the collapse. Band members were fully focused on the Bungalow policy discouraging Black patrons. The Bungalow, despite having featured Ellington, Cab Calloway and Lionel Hampton among dozens of acts, remained a segregated venue. Determeyer reports that the date of Lunceford’s appearance in Seaside, some of the customers were Black, so the Bungalow management offered Lunceford’s valet $50 to discourage black couples waiting to purchase tickets from buying by telling them, “They don’t want to sell tickets to people like us.” Wilder, the first trumpeter, refused to play, and the band couldn’t, or wouldn’t, play without him. “Finally, Eddie Rosenberg, who was the manager, came back,” Wilder said. “He had gone with Jimmie to the hospital. But he didn’t tell us that Jimmie had died, you see. He said, ‘When Jimmie comes back, he — naturally, he wouldn’t play, if he knew the circumstances. But if we don’t play, then the contract becomes null and void. So why don’t we just play, so that we fulfill our obligations?’ At that point, I said, OK, and we played. It was at the intermission that he told us that Jimmie had died.” End of an era The show, despite Lunceford’s death, went on that night, Determeyer wrote, but one musician after the other left the bandstand and headed to the restroom. “I’m the only one that didn’t get sick,” Parham said. “Botulism, you know.” A preliminary examination by Clatsop County coroner William Thompson “revealed that death was due to natural causes,” wire services wrote. An autopsy performed by Dr. Alton Alderman in Astoria — about 15 miles north of Seaside — disclosed that Lunceford died of coronary occlusion. A memorial service with remaining band members took place that week at Rockaway Beach, the last concert before the Lunceford orchestra permanently disbanded. According to the Memphis Commercial Appeal in their obituary, his band played its scheduled engagement an hour later. It was a one-night stand on a West Coast tour, their last performance, announced by band manager Rosenberg. At the request of his wife, Crystal, Lunceford’s body was flown to New York City for the funeral service. Returned to Memphis, a procession of family, friends, and band members accompanied Lunceford's casket to the historic Elmwood Cemetery. Returned to Memphis, a procession of family, friends, and band members accompanied Lunceford’s casket to the historic Elmwood Cemetery, wrote Scott Stanton. Before long, Determeyer wrote, “the myth surrounding Lunceford’s death was in full swing.” Seaside’s Linkey thought it was unlikely Lunceford and his bandmates were deliberately sickened or worse, or even turned away from a Seaside restaurant. She added the idea of poisoning “takes giant leaps” in suggesting a racial incident was a factor in Lunceford’s death. Jazz historian Lewis Porter pointed out that botulism, as suggested by Truck Parham as the source of Lunceford’s death, is not a poison and cannot be “manufactured” or “planted,” Porter said. “It’s simply a severe form of food poisoning that can occur in, for example, rotten meat,” Porter said. “But he (Lunceford) died from a heart attack—nothing to do with the food! He’s not the first guy to die suddenly at a relatively young age from unsuspected heart trouble, especially in those days.” Ronald Cortez Herd II, an expert on Lunceford, his life and music, visited Seaside in 2016 from his home in Memphis, Tennessee, in search of clues to the bandleader’s sudden death, and has spent years tracking down theories. He learned theories abound about Lunceford’s death, including Lunceford was killed by gangsters for rights to his music. Others were convinced Lunceford died in a mysterious plane crash like that of bandleader Glenn Miller. The incident in Portland at the restaurant the night before his death conflated the question. Even eyewitnesses disagreed. In 2023, Herd spoke to Lunceford’s relatives at a family reunion in Mississippi. He suggested that they should exhume his body and “find out the truth once and for all.” “Many of them agreed,” Herd said via Facebook messenger this month. “What makes the Jimmie Lunceford story so compelling is that it is still contested how he actually died. … Jimmie Lunceford’s music legacy is incredible, but his death is also intriguing.”