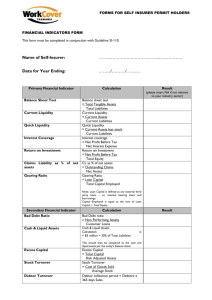

Table of Contents Topic 1A .................................................................................................................. 4 Financing ........................................................................................................................ 4 Why? ................................................................................................................................................4 Investment vs. Financing ....................................................................................................................4 Direct vs. Intermediated Funding ...................................................................................... 4 Direct Funding Risks: .........................................................................................................................4 Intermediated Funding Risks ..............................................................................................................4 Risks of Funding ................................................................................................................................5 Roles of Bank .................................................................................................................. 5 Topic 1B .................................................................................................................. 6 Balance sheets ................................................................................................................ 6 Banking trends ................................................................................................................ 6 Regulators....................................................................................................................... 6 US regulatory bodies ..........................................................................................................................6 AUS regulators...................................................................................................................................6 Topic 2 .................................................................................................................... 7 Bank Financial Statements .............................................................................................. 7 Balance Sheet ...................................................................................................................................7 Relationship Between the 2 Reports ...................................................................................................8 OL Balance Sheet Items (OBS Items) ..................................................................................................8 Assessing Performance with Ratios .................................................................................. 9 Ratios ...............................................................................................................................................9 Topic 3A ................................................................................................................. 10 Liquidity risk ...................................................................................................................11 Causes of Liquidity Risk ................................................................................................................... 11 Wholesale liability side .................................................................................................................... 13 Lender of Last Resort ......................................................................................................13 Measuring Liquidity Exposure ..........................................................................................14 Peer Group Ratio Comparison .......................................................................................................... 14 Net Liquidity Statement ................................................................................................................... 15 Liquidity Index ................................................................................................................................. 15 Financing Requirement .................................................................................................................... 15 BIS Approach, Maturity Ladder/ Scenario Analysis ............................................................................ 15 Regulatory Treatment ....................................................................................................................... 16 Topic 3B ................................................................................................................. 17 Bank Runs ......................................................................................................................17 Deposit Insurance and the FDIC ....................................................................................................... 17 FSLIC .............................................................................................................................................. 18 pg. 1 Mitigating Moral Hazard ................................................................................................................... 19 Systematic Costs/Benefits of Deposit Insurance ............................................................................... 20 During Market Stress ........................................................................................................................ 21 Deposit Insurance in Australia .......................................................................................................... 21 Topic 4A ................................................................................................................. 22 Loanable Funds Theory (How are Interest Rates Determined?)..........................................22 Yield Curve .....................................................................................................................22 Interest Rate Risk ...........................................................................................................23 Cash flow risk – Type 1 of Interest rate risk......................................................................................... 23 Market Value Risk – Type 2 of Interest rate risk ................................................................................... 24 Repricing Model – Measures Cash Flow Interest Rate Risk................................................................. 25 Topic 4B ................................................................................................................. 26 Maturity Model ...............................................................................................................27 Duration Model ...............................................................................................................28 Macauley’s Duration ........................................................................................................................ 28 Immunising the whole balance sheet of an FIs .................................................................................. 29 Duration Model Limitations ............................................................................................................. 30 Duration and Convexity .................................................................................................................... 30 Demand Deposits and Savings Deposits Problem ............................................................................. 30 Topic 5a ................................................................................................................. 31 Loans .............................................................................................................................31 Evaluating Loans ............................................................................................................................. 31 Credit Quality Problems ................................................................................................................... 31 The Contractually Promised Return on a Loan ................................................................................... 31 The Expected Return of a Loan ......................................................................................................... 32 Retail Versus Wholesale Credit Decisions ......................................................................................... 32 Credit Risk .....................................................................................................................33 Measuring Credit Risk ...................................................................................................................... 33 Default Risk Models ......................................................................................................................... 34 The Term Structure of Credit Risk ...................................................................................................... 36 RAROC ............................................................................................................................................ 38 Option Models of Default Risk .......................................................................................................... 39 Topic 5b ................................................................................................................. 40 Simple Models of Loan Concentration Risk ......................................................................40 Migration Analysis............................................................................................................................ 40 Concentration Limits Approach ........................................................................................................ 40 Loan Volume Based Models ............................................................................................................. 40 Regression Based Models ................................................................................................................ 41 Loan Portfolio Diversification and Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) ....................................................... 41 KMV Portfolio Manager Model ........................................................................................................... 42 Credit Metrics.................................................................................................................................. 42 Topic 6 ................................................................................................................... 43 Regulation ......................................................................................................................43 Leverage (capital) Ratio .................................................................................................................... 44 pg. 2 Basel 1 ............................................................................................................................................ 45 Basel 2 ............................................................................................................................................ 47 Basel 3 ............................................................................................................................................ 48 Topic 7 ................................................................................................................... 49 Securitisation .................................................................................................................49 Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 49 What is (loan) securitisation? ........................................................................................................... 50 Motivations ..................................................................................................................................... 51 Credit Default Swaps (CDS).............................................................................................................. 53 OL Balance Sheet Subsidiaries ........................................................................................................ 53 Topic 8 ................................................................................................................... 63 Issues Covered ...............................................................................................................63 Sub Prime Housing Problems ..........................................................................................63 Big Picture Causes ........................................................................................................................... 63 Demise of “originate and hold” ......................................................................................................... 65 Shadow Banking and Commercial Paper Markets .............................................................65 In search of yield and shadow banking .............................................................................................. 65 SIVs ................................................................................................................................................ 66 Liquidity Problems ABCP.................................................................................................................. 67 Demise of Shadow Banks ................................................................................................................. 68 Traditional Vs Securitized Banking ...................................................................................68 Repo Market ...................................................................................................................69 Liquidity Problems ..........................................................................................................69 Interbank ........................................................................................................................................ 69 Repo ............................................................................................................................................... 70 Topic 9 ................................................................................................................... 70 Silicon Valley Bank – Interest rate risk ..............................................................................70 Northern Rock – Liquidity Shock (i.e. Bank Run) ................................................................71 Continental Illinois – Concentration risk ..........................................................................71 Washington Mutual Bank – Everything goes wrong. ...........................................................72 pg. 3 Topic 1A Financing Why? 1. Consumers: Smooth Consumption: Smooth consumption creates more utility/preference 2. Entrepreneurs: Mismatch Between Ideas and Capital Investment vs. Financing § § § § Investment (Capital Budgeting): Allocation of investments given food of funds. Financing (Capital Structure): Sourcing funds given investments. Equity financing (Direct): Equity ownership (shares) Debt financing: Debt financing can be intermediated or direct (between individuals). Generally, debt financing is private (banks) or public (bonds) Direct vs. Intermediated Funding § § Direct Funding: Money between individuals - Few investors are willing to invest in highrisk projects. Risk Factors in Financing: o Credit/Default Risk: The risk that borrowers may fail to repay their debts. o Liquidity Risk: Risks associated with being able to liquidate investments when needed. Direct Funding Risks: § § § Credit risk is assessed by looking at, information asymmetries, moral hazards, and agency costs (costs to overcome agent’s risk to work in the best interest of the principal, or cost from agent not working in best interest) o Overcoming these costs: Debt covenants, monitoring. Other risks: direct funding less liquid, and carries price risk as there is no market and individuals don’t want to take on debt. Little/no monitoring would occur, riskiness of investments would increase, high liquidity risk, and as a result willingness to invest falls. Intermediated Funding Risks § Agglomeration of funds: reduce information costs/risk (quality of information received), information collection and monitoring (no free-rider problem – free-rider pg. 4 § § problem is where they know they’re not going to be monitored – and delegated monitoring), development of secondary securities to monitor (e.g. Short term debt contracts are easier to monitor than bonds -> maintenance covenants) Secondary claims/securities (right to receive deposits): Provide depositors with safe assets, increased liquidity over direct funding, and these secondary securities are more marketable. o Financial institutions do this by: Diversification (reduces impact of credit risk or liquidity risk) Overall, intermediation reduces risk and increases willingness to invest by reducing information costs and liquidity costs, through monitoring and diversification. o Increased marketability Risks of Funding § § § § § Riskier investments are often in debt because they get paid out first. Payment & Pricing: Repayment schedule, interest rate, additional fees (processing, late charges). Risk-Based Pricing: Higher risk borrowers pay higher interest. Information Gathering: Borrower provides financial statements, tax returns, etc. Covenants: o Positive/Maintenance Covenants: Borrower must maintain certain financial ratios (e.g., debt-to-equity). o Negative/Incurrence Covenants: Borrower restricted from certain activities (e.g., taking on more debt). Roles of Bank 1. Asset transformation (Liquidity creation) – Beginning of topic 3A 2. Delegated Monitoring pg. 5 Topic 1B Balance sheets § § § Bank performance is compared using ratios from the balance sheet, ROA, ROE Suggestions for reform often involve increasing capital adequacy (capital/risk weighted assets) or equity requirements. Banks are highly leveraged and hold little equity compared with total assets. o Risk of insolvency from defaults on loans Banking trends § § Mergers and acquisitions (consolidations) have led to few banks, a high concentration of large banks. In Australia, new banks are on the rise. There has also been a rise in non-banks (shadow banks), these don’t take deposits. Regulators US regulatory bodies § § § § FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation): Insures deposits up to $250k, manages deposit insurance fund, and conducts bank examinations. OCC (O_ice of the Comptroller of the Currency): Charters national banks and oversees mergers, a sub-agency of the US Treasury. FRS (Federal Reserve System): Acts as the central bank, regulates some banks and bank holding companies, and influences monetary policy. State Bank Regulators: Coexist with national banks, overseeing state-chartered banks. AUS regulators § § § Australia's financial regulation framework stems from the late 1990s' Financial System Inquiry (Wallis Committee). All recommendations from the inquiry were implemented by 1999. The Wallis Committee proposed the establishment of three agencies: APRA, ASIC, and the RBA. 1. APRA (Australian Prudential Regulation Authority): • Oversees various financial entities including banks, credit unions, insurers, and superannuation funds. • Focuses on developing prudential policies to ensure financial safety, competition, and neutrality. pg. 6 • • APRA sets prudential standards for Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions (ADIs) under the Banking Act 1959. Standards cover areas such as capital adequacy, risk management, and governance. 2. RBA (Reserve Bank of Australia): • Responsible for monetary policy implementation and ensuring financial system stability. • Aims for low and stable inflation over the medium term. • Acts as a lender of last resort and oversees macro-prudential regulation. o 3. ASIC (Australian Securities and Investments Commission): • Ensures market integrity and consumer protection in the financial system. • Sets standards for financial market behaviour and enforces relevant laws such as the Corporations Act 2001 and National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009. Topic 2 Bank Financial Statements § There are 2 key reports from which we will find the data we need for our ratios 1. The Balance Sheet, information about assets and liabilities. 2. The income statement, it shows how the balance sheet changes with time through income and expenses. Balance Sheet § § Net Loans = Gross Loans – Allowance for Possible Loan Losses Loan Accounts: o Gross Loans: sum of all loans o Nonperforming Loans: 90 days past due loans o Charge-oPs: Failed loans o Allowance for Possible Loan Losses pg. 7 § § § Contra asset account (either zero or credit negative balance) § For potential future loan losses Adjusted allowance for loan losses = Beginning allowance for loan losses + provision for loan losses (this is from the income statement) Ending allowance for loan losses = Adjusted allowance for loan losses – actual charge-o_s + recoveries from previous charge-o_s Relationship Between the 2 Reports § " Net income 𝑁𝐼 = ∑" !#$ 𝑟! 𝐴! − ∑%#$ 𝑟% 𝐿% − 𝑃 + 𝑁𝐼𝐼 − 𝑁𝐼𝐸 − 𝑇 o Interest rates, and assets for the ith asset; interest rates and liabilities for the jth liability; P is loan provision; NII is non-interest income; NIE is non-interest expenses; T is income tax. OF Balance Sheet Items (OBS Items) § § OBS items are contingent assets and liabilities that may impact the future status of a financial institution's report of condition Unused Commitments. OBS items o Derivative activity: 1. Swaps, forwards, OTC options, credit derivatives 2. Futures, ETO options of futures, ETO options on stocks o Liquidity support facilities / lending related: Loan commitments (contingent asset), letters of credit (LOC) (contingent liability), standby LOCs, loan sales with resource o Securitisation moves assets OBS § Common OBS assets include accounts receivable, leaseback agreements, and operating leases. pg. 8 Assessing Performance with Ratios '() ) § ! We can value a firm using: 𝑃& = ∑.#& ($+,)! § Value of a Bank’s Stock Rises When: o Expected Dividends (profit) Increase o Risk of the Bank Falls o Market Interest Rates Decrease o Combination of Expected Dividend Increase and Risk Decline Ratios DuPont Analysis ROE 𝑁𝑒𝑡 𝐼𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒 (𝑎𝑓𝑡𝑒𝑟 𝑡𝑎𝑥𝑒𝑠) 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝐸𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝐶𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 Is the amount of income after taxes earned for each dollar of equity capital A bank with higher ROE is generally preferred; however, an increase in ROE could indicate an increase in risk ROE increase when equity capital falls. This will happen if a bank alters its capital structure (increases debt) In other words an increase in ROE might be a result of increased leverage which implies: (a) an increase in financial risk; (b) increased likelihood of a regulatory violation 𝑅𝑂𝐸 = § § § § ROA 𝑁𝑒𝑡 𝐼𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒 (𝑎𝑓𝑡𝑒𝑟 𝑡𝑎𝑥𝑒𝑠) 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝐴𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 Amount of income after taxes earned for each dollar of assets 𝑅𝑂𝐴 = § pg. 9 EM (equity multiplier) 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝐴𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝐸𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑡𝑦 Is a measure of leverage (not just for banks EM relates ROA and ROE 𝑹𝑶𝑬 = 𝑹𝑶𝑨 × 𝑬𝑴 𝐸𝑀 = § § Other Important Ratios § § § § Interest income ratio: IIR = Interest income / TA Non-interest income ratio: NIIR = Non-interest income / TA Net interest margin: NIM = (interest income – interest expense) / Earning assets The spread: Spread = (interest income / earning assets) – (interest expense / interest bearing liabilities) o Because of the historical flattening of the yield curve banks couldn’t make as much from the spread, so securitization has become more common (pooling and selling of assets). Limitation of ratios § § § A variation of one number can be caused by many things but may indicate something very di_erent when in ratio. Ratios be assessed across time. Not forward looking (doesn’t account for market risk, interest rate risk, nor credit risk) Topic 3A § § § Recite that the two main things that banks do is liquidity creation and delegated monitoring. Liquidity creation is the process of using the balance sheet converting liquid shortterm liabilities into illiquid long-term assets. This process is called asset transformation. Asset transformation o Liquidity creation: Illiquid -> liquid § This gives rise to liquidity risk. o Maturity intermediation: Long-term -> short term § This gives rise to interest rate risk. pg. 10 Liquidity risk § § § § Banks hold fewer liquid assets than they have liabilities (E.g., deposits), because of this mismatch of liquid assets to liabilities banks are subject to liquidity risk. Sources of liquidity risk 1. Deposit holders request to withdraw funds. 2. Wholesale funding “withdrawals” 3. OBS demand from contingent assets/liabilities – e.g. If lots of people who have existing credit cards starting using them more, this contingent asset converts cash and liquid assets into an illiquid asset. If a bank runs out of liquid assets: they must either get an expensive form of funding or sell illiquid assets at a large cost. Banks hold such a small amount of cash and liquid assets because: o Costly to do so (opportunity cost) o Liquidity is a result of liquidity creation and is part of the everyday management of a DI Causes of Liquidity Risk Retail Liability Side § § § Everyday only a portion of deposits are withdrawn, as well as new deposits made. o Hence, consider deposits as a total (CORE DEPOSITS), and we concern ourselves about the NET DEPOSIT DRAIN Managing this risk Stored liquidity management o Banks can use historical deposit flow data to generate a distribution, then pg. 11 § simulate the distribution under certain scenarios, holding su_icient cash to meet the expected net drain. § Involves liquidating assets: cash in vaults, cash on deposit at central banks, government and semi-government securities, and other liquid assets o Banks mostly don’t like as its costly to hold cash and other highly liquid assets, and shrinks asset size (size of bank) Purchased liquidity management 1. If long enough time horizon (> week, say) sell wholesale certificates of deposit, notes, bonds § This replaces one form of funding (low/no interest paying deposits) with a more expensive form of funding. § If the DI is in distress then these methods may be very expensive or simply not available. 2. Interbank borrowing (very short-term, overnight to 1-week) @ LIBOR § Libor is average of how much each bank can borrow from each other 3. Repo markets (cash borrower = repo seller) § Collateralised interbank transactions § Usually backed by government securities § Highly liquid and flexible source of funs § Cost • Yield generally below the market interbank rate due to collateralised nature (from interbank market) • Generally below cash/fed funds rate (from central bank) • Pricing: repo rate vs. haircuts Note: As seen in the balance sheets, stored liquidity management responds to a deposit drain by decreasing cash to match the decrease in deposits. While purchased liquidity management responds to a deposit drain by altering the composition of liabilities from deposits to borrowed funds whilst the asset side remains unchanged. pg. 12 Asset Side § § § Loan commitments and other contingent assets/liabilities on the OBS increase the cash demand for banks and can bring about a shortage of cash. o E.g. Contingent assets (like a loan request – credit card) and the exercise by borrowers of their loan commitments and other credit lines o We face the same problems as with liquidity drains from the liability side. We consider two common OBS items o Commitments (contingent asset) o Letters of Credit (contingent liability) Managing this Risk o Purchases liquidity management – Borrowed funds increase on the liabilities side. o Stored liquidity management – Decrease in cash on the assets side. § E_ects of loan commitment being exercised (Loan commitment exercised, borrower has decided to take out loan as agreed, and the lender now obligated to provide fund) Wholesale liability side § § § Relying on purchased liquidity can be a problem in times of market stress o Very volatile, Markets might dry up When you can’t refinance in the wholesale market and you’re heavily dependent on it, a “bank run” in the wholesale market ensues (e.g. Northern Rock). LLR comes in Lender of last resort (LLR): the central bank (known as the discount window in the US) Lender of Last Resort § § To prevent the bank running out of cash, the central bank acts as the lender of last resort, known as the discount window in the US. Central banks act as a liquidity backstop for banks in times of need. pg. 13 § § § § § o Problematic as it encourages banks to hold little cash knowing that the government will step in and help them if necessary. The Fed’s discount window involves banks borrowing from the Fed on a short-term basis under repo transactions where discounts are applied to the collateral. There are 3 levels of funding: o Primary credit (financially sound institutions) § cost = Fed's funds rate + 50 bp o Secondary credit (institutions not eligible for primary credit) with bigger haircuts on collateral than primary and greater fed oversight. § cost = primary rate + 50 bp, o Seasonal (only for small institutions demonstrating clear seasonal patterns) § cost varies. During the GFC the Fed implemented a number of programs including Extension of discount window lending to support the liquidity of financial institutions and foster improved conditions in financial markets. In Australia the stability of the financial system is a responsibility of the RBA. This is done on an intra-day and overnight basis using repos (same as the Fed’s discount window) - The RBA buys securities under repurchase agreements in two broad classes of securities. o General collateral (Commonwealth Gov. securities, Semi-government securities), and private securities (Credit rated ADI issued securities, including covered bonds, with a maturity one year or less). Historically, banks using the discount window were not named so it didn’t create a bank run o Now however is reported with a 2 year lag in USA, but still secret in Australia Measuring Liquidity Exposure § We look at 5 methods: Peer Group Ratio Comparison § § We can compare certain key ratios and balance sheet features of one DI with similar Dis or to some market-wide benchmark E.g. o Purchased or borrowed funds/total assets o Deposits/ total assets (higher = less liquidity risk) o Loans/ Deposits (higher = illiquid) pg. 14 o Loan commitments/ assets o Cash and Due from banks/ total assets Net Liquidity Statement § § § The net liquidity statement: Shows sources and uses of liquidity o Net liquidity = Sources – Utilisation The sources are: (i) cash type assets, (ii) maximum amount of borrowed funds available, (iii) excess cash reserves The utilisation includes: o Funds borrowed, and any amounts already borrowed from the Fed Liquidity Index § It measures the potential loss a DI could su_er from a sudden disposal of assets, compared to the amount it would receive (by selling over some period) under normal market conditions. Financing Requirement § § § § Straight from the balance sheet o 𝐹𝑖𝑛𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑔𝑎𝑝 = 𝑎𝑣𝑔 𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑛𝑠 − 𝑎𝑣𝑔 𝑑𝑒𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑖𝑡𝑠 § A positive gap means that the DI requires funding The financing gap can also be defined as: o 𝐹𝑖𝑛𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑔𝑎𝑝 = 𝑏𝑜𝑟𝑟𝑜𝑤𝑒𝑑 𝑓𝑢𝑛𝑑𝑠 − 𝑙𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑑 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 This financing requirement (i.e. Borrowed funds/wholesale funding) is defined as the financing gap plus a DI’s liquid assets o 𝐹𝑖𝑛𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑅𝑒𝑞. = 𝐿𝑜𝑎𝑛𝑠 − 𝐷𝑒𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑖𝑡𝑠 + 𝐿𝑖𝑞. 𝐴𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 The larger a DI’s financing gap and liquid asset holdings, the greater the exposure BIS Approach, Maturity Ladder/ Scenario Analysis § § BIS: Bank for International Settlements For each maturity, assess all cash inflows versus outflows o Cash inflows being sources and cash outflows being utilisation pg. 15 § § § Daily and cumulative (e.g. monthly) net funding requirements can be determined in this manner Must also evaluate ‘what if’ scenarios in this framework Used by APRA Regulatory Treatment Basel III and Liquidity for Australian ADI’s § § During the GFC many banks had adequate capital levels however, this capital needed to be more liquid to prevent such a crisis from occurring again Basel III has introduced two new minimum standards for liquidity risk supervision 1. Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR): to ensure short-term resilience of ADIs to liquidity risk by ensuring they hold su_icient high-quality liquid assets to survive a significant stress scenario lasting for 30 days 2. Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR): to ensure long-term resilience by creating additional incentives for banks to fund their activities with more stable funding on an ongoing basis. The NSFR test is similar to the LCR except the horizon is one year Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) § § § § § ADIs are required to maintain an adequate level of unencumbered, high-quality liquid assets to meet their liquidity needs for a 30-day period under a significantly severe stress scenario. It must not be less than 100% 𝑆𝑡𝑜𝑐𝑘 𝑜𝑓 ℎ𝑖𝑔ℎ 𝑞𝑢𝑎𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑙𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑑 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 𝐿𝐶𝑅 = ≥ 100% 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑛𝑒𝑡 𝑐𝑎𝑠ℎ 𝑜𝑢𝑡𝑓𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑠 𝑜𝑣𝑒𝑟 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑛𝑒𝑥𝑡 30 𝑐𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑎𝑟𝑑 𝑑𝑎𝑦𝑠 Numerator: High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) refers to assets that are highly liquid and of a very high quality with regards to marketability and credit quality Denominator: Total net cash flows are calculated according to the Basel III scenarios. Problem with LCR for Australian banks: It was impossible for banks in Australia to all meet the LCR requirements given the small number of HQLA. The solution was make the RBA provide liquidity with a fee. This was chosen over making banks to hold foreign liquid assets. pg. 16 Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR): § ADIs are required to maintain a minimum acceptable amount of stable funding based on the liquidity characteristics of their assets and activities over a one-year horizon. o Must not be less than 100% 𝐴𝑣𝑎𝑖𝑙𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝑎𝑚𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝑓𝑢𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑁𝑆𝐹𝑅 = ≥ 100% 𝑅𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑎𝑚𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝑓𝑢𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔 o Household deposits are now treated as a stable source of funding. Topic 3B Bank Runs § § § § § § § § Traditional focus is on liquidity risk from deposits Normal times, bank can manage liquidity risk quite easily o Liquidity demands from depositors are uncorrelated (or negatively correlated) Bank run is a swift mass withdrawal of deposits (drain) o Liquidity demands from depositors are (strongly) positively correlated Incentive to bank run: o CAN discipline banks for risky behaviour o Banks hold very little cash o Sequential service feature of deposit contract means, ‘first in, best dressed’ o So if there is market stress, depositors do not want to be the ones to miss out o In economic speak, this is a co-ordination problem among depositors In old days ‘closing the doors’ was one strategy bank employed to slow the drain of deposits. Today we consider an alternative government mechanism to prevent runs: deposit insurance One bank run can see other banks get mass drain as well out of fear If depositors are uninsured, depositors will pay more attention to banks activities Deposit Insurance and the FDIC § § § FDIC created in 1933 in wake of banking panics during 1930-33 Insurance is not free! (usually) o US Banks are charged a fee for this coverage by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Insurance fees are stored in the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) which invests in US Treasuries pg. 17 § § § § IF payment is needed o Payments are made to claimants (deposit holders in failed banks) from the DIF. o This takes place ASAP, usually within 2 business days of the failure. o The priority of payments is insured depositors, uninsured depositors, followed by general creditors and then stockholders. In most cases, general creditors and stockholders realize little or no recovery PROCESS 1. OCC (or State regulator) shuts down bank (i.e. revoked its charter) 2. FDIC seizes assets and auctions o_ the ‘entire’ bank in purchase and assumption agreements. They sell them the assets at a discount if they also assume the deposits. 3. If no one purchase the deposits, then DIF physical pays out depositors The DIF typically makes a loss when a failure occurs, even if assets are sold The DIF sweetened the deal of ‘purchase and assumptions agreements’ with loss/risksharing agreements in which the DIF pays o_ a portion of future losses of the inherited assets FSLIC § § FSLIC was another deposit insurance fund, the Federal Savings and Loans Insurance Corporation (FSLIC) covered savings and loans institutions (basically a bank). Their net worth dropped from $40 billion to negative $80 billion during the savings and loans crisis from 1989-92 and failed themselves. o Eventually they merged to form the DIF. o Why did the FSLIC fail: Economic Environment § § Economic environment o Rise in interest rates o Collapse in oil, real estate, and commodity prices o Increased competition § Domestic and foreign A similar pattern in the late 2000s: o Housing market collapse and demise of high profile FIs o Consumer loan defaults pg. 18 Moral Hazard § § Moral hazard describes the possibility that one party may take undue risks because the costs are not borne by that party. o Q: who/what is the party here? o Both depositors and the banks Deposit insurance encouraged under-pricing of risk and reduced depositor discipline o Premiums not linked to risk § (e.g. Risky banks and safe banks paying same deposit rate) o Inadequate monitoring § (e.g. If bank knows you aren’t watching them, they take risk) o These both lead to higher risk taking Regulatory Forbearance § § § § Regulatory Forbearance: Regulators were too relaxed Capital forbearance permits banks to continue operating even when their capital is depleted Policy of capital forbearance lead to an accumulation of greater losses. o Allowing failing banks to continue to operate E.g. bank runs out of capital and regulators give them a one more year to operate like that, they take more risk to try recoup those losses as they’re not risking losing anything (playing poker with someone else’s money) Mitigating Moral Hazard § Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act (FDICIA), incorporated 3 solutions: 1. Increase bank/stockholder discipline – Link the insurance premiums with the asset mix, and categories of liabilities (un/insured, non/contingent) 2. Increase depositor discipline – If have unlimited insurance, there's is no need to monitor the bank. There was a cap put on retail deposits insurance of $100,000, now $250,000. Corporate deposits are uninsured. pg. 19 3. Increase regulatory discipline – Went from a discretionary basis to a category system of how well capitalised the bank is with risk (capital adequacy) and leverage ratios (1B balance sheet and Equity multiplier, respectively) Systematic Costs/Benefits of Deposit Insurance § § § Ex-ante: Before the event Ex-post e_icient: After the event The NSFR (3A Basel III) was put in place because during times of crisis, a bank needs stable funding because of the growth of loans from OBS items like credit cards, but also a bank struggles to get funding on the interbank market. Because of the safety of banks (deposit insurance), deposits flow into a bank during a time of crisis – like a hedge. Costs - Ex-ante ineMicient § § Cross country analysis has shown having deposit insurance o Increases the likelihood of crisis (moral hazard) o Reduces market discipline (sensitivity of financing cost to risk) These are ex-ante costs (i.e. deposit insurance is ex-ante ine_icient) o ex-ante is a estimate of costs before they are incurred Benefits – Ex-post eMicient § § US based studies show that banks funded more out of deposits during the crisis contracted lending less o Why? As deposits are a stable source of funding (compared to wholesale markets) o How? Only due to insurance? Some preliminary evidence suggests this is the case The contemporary view of liquidity risk o Bank use deposits to hedge liquidity risk on asset side (from commitments) pg. 20 § Only possible if liquidity demands for deposits and commitments are negatively correlated (should be the case in times of market stress) o Only if deposits are safe though During Market Stress Deposit Insurance in Australia § The scheme is administered by APRA and operates as follows. o The Scheme is activated at the discretion of the Australian Treasurer where APRA has applied to the Federal Court for an ADI to be wound up. This can only be done when APRA has appointed a statutory manager to assume control of an ADI and APRA considers that the ADI is insolvent and could not be restored to solvency within a reasonable period. o Upon its activation, APRA aims to make payments to account-holders up to the level of the cap as quickly as possible – generally within seven days of the date on which the FCS is activated. o The method of payout to depositors will depend on the circumstances of the failed ADI and APRA's assessment of the cost-ePectiveness of each option. pg. 21 Payment options include cheques drawn on the RBA, electronic transfer to a nominated account at another ADI, transfer of funds into a new account created by APRA at another ADI, and various modes of cash payments. Topic 4A Loanable Funds Theory (How are Interest Rates Determined?) § § § § Interest rates reflect supply and demand for loanable funds. Conventional monetary policy: Central can change interest rates by setting rates for housing or business loans. Unconventional monetary policy: Through open market operations (OMO) (buying or selling bonds). E.g., A central bank can print money and buy bonds to increase the supply of money (quantitative easing). A change in approaches from targeting interest rate goals towards inflation targeting increased interest rate volatility. This happened in 1993 in Aus and in 2012 in the US. Yield Curve § § What determines term structure? (yield curve shape). o The shape of the yield curve is determined by the expectation of future short term interest rates. Downward sloping if future short term interest rates are expected to fall and vice versa. A downward sloping yield curve is an indicator of a recession. There three main reasons that the yield curve is expected to upwards slopping: 1. Expectations hypothesis (expectations of future interest rates), 2. Liquidity premium theory (premium for holding long-term bonds), 3. Market segmentation theory (financial instruments of di_erent terms are not interchangeable so they are priced separately) o Generally, the yield curve is upward sloping due to the liquidity premium hypothesis. This is how banks used to make their spread by investing in long term securities whilst paying out short term rates on deposits. o The segmented market hypothesis explains the shape of the yield curve by di_erent market participants having preferences with di_erent maturities. Suggesting that yields of di_erent maturities are determined independently. pg. 22 § § A 'flat' yield curve occurs when short-term yields are similar to long-term yields. This can happen during transitions between a normal and inverted yield curve, at low interest rates, or due to unconventional monetary policies. § An 'inverted' yield curve occurs when short-term yields are higher than long-term yields, sloping downward. This often signals that investors expect lower future interest rates. In the U.S., an inverted yield curve has historically preceded economic contractions, as central banks lower rates in response to slowing growth and inflation. -A 'normal' yield curve occurs when short-term yields are lower than long-term yields, sloping upward. This reflects higher yields for long-term bonds due to uncertainty about future interest rates or inflation. A normal curve is common during economic expansion, when growth and inflation are rising, leading investors to expect higher future interest rates. Interest Rate Risk § § § Interest rate risk is incurred by an FI when it mismatches the maturities of its assets and liabilities. The danger is that shifting IRs may adversely a_ect a bank’s net Income, the value of its assets and therefore equity. Two sources o Cash flow risk o Market value risk Cash flow risk – Type 1 of Interest rate risk § § Most FI’s are short funded Financial intermediaries can be short funded (banks generally) or long funded (insurance companies). Short funded meaning the maturities of liabilities are shorter than that of their assets and long funded meaning their liabilities have longer maturities than their assets. Thus: o Short funded refinancing risk is the possibility that the costs of rolling over or reborrowing funds will rise above the returns generated on investments. § (E.g., 2yr Fixed Loan with a 1yr Term Deposit) o Long funded reinvestment risk is the possibility that the return on reinvested funds falls below the cost of funds. pg. 23 § (E.g., 5yr Term Deposit with a 1yr Fixed Loan) IR Risk Ratios § § § Interest Sensitive Assets / Interest Sensitive Liabilities Uninsured Deposits / Total Deposits Interest Bearing Deposits / Total Deposits Market Value Risk – Type 2 of Interest rate risk § § § § § § § As interest rates increase, the market value of assets and liabilities decrease (increased discount rate) As interest rates decrease, the market value of assets and liabilities increase (decreased discount rate) If the FI mismatches the maturities of its assets and liabilities, the change in market value of assets and liabilities will not be the same As 𝑬𝒒𝒖𝒊𝒕𝒚 = 𝑨𝒔𝒔𝒆𝒕𝒔 − 𝑳𝒊𝒂𝒃𝒊𝒍𝒊𝒕𝒆𝒔, changing interest rates can have an adverse impact on the DI’s net worth Market value ePects mean equity value falls/ rises to balance the above equation The longer the maturity, the greater the impact of interest rate changes Ideally, FIs should match the maturities of assets and liabilities. o Balance sheet hedging by matching maturities of assets and liabilities is problematic for FIs.. o For most FIs the maturity of assets exceeds the maturity of liabilities If Short Funded: § Assume the maturity of assets exceeds the maturity of liabilities: a. An increase in interest rates causes a fall in the market value of both assets and liabilities, but assets are more severely a_ected b. A decrease in interest rates causes an increase in the market value of both assets and liabilities, and liabilities will increase less than assets. If Long Funded: § Assume the maturity of liabilities exceeds the maturity of assets: pg. 24 a. A decrease in interest rates causes a rise in the market value of both assets and liabilities, but liabilities are more severely a_ected. b. An increase in interest rates causes a fall in the market value of both assets and liabilities, and assets will decrease less than liabilities Repricing Model – Measures Cash Flow Interest Rate Risk § § § § § § § § § § The repricing (funding gap) model concentrates on the impact of IR changes in a bank’s net interest income (NII) It is simple and gives a direct insight into the balance sheet; it is a book value accounting cash flow analysis of the repricing gap between interest earned and paid, i.e., It’s an accounting model! The model does not capture the e_ects of rising/falling interest rates on net worth (market value) o Market value e_ect is measured by the maturity and duration models Repricing Gap = Rate sensitive assets – Rate sensitive liabilities. o 𝐺𝑎𝑝! = 𝑅𝑆𝐴! − 𝑅𝑆𝐿! § Rate sensitive assets include: T-notes (of various maturities); floating-rate long term loans; variable-rate mortgages § Rate sensitive liabilities include term deposits, short-term paper • i.e, if the interest rate could be changed within a specified period (be repriced) Under Basel II, ADIs are required to lodge a repricing analysis form with APRA quarterly Most banks use the repricing model as an interest rate risk measurement tool Repricing can be the result of a rollover (e.g. renewal of deposit/loan) of an asset or liability, or it is variable rate (e.g. rate being reset each quarter). Its di_icult to determine whether an asset/liability is rate sensitive. E.g. of RSL: Everyday spending / cheque account o Reasons it should not be included: rates near zero, core deposits (little movement) o Reasons it should be: Runo_s (if interest rate rise à invest money or put in savings) The model can be used to estimate the change in the FI's net interest income in a particular repricing bucket (time frame) if interest rates change o Net Interest Income (NII) – For a set maturity: ∆𝑁𝐼𝐼! = (𝐺𝑎𝑝! )∆𝑅! = (𝑅𝑆𝐴! − 𝑅𝑆𝐿! )∆𝑅! Cumulative Gap (𝐶𝐺𝑎𝑝! ) The cumulative gap is found by adding the gaps of di_erent periods. pg. 25 § o CGap/Assets provides the direction and scale of interest rate exposure for a bank. Advantages and disadvantages o Advantages – information value, simple, transparent o Weaknesses – Ignores market value ePects, over-aggregation (sudden drops and rises in the repricing gap may be aggregated out), run-o_s, does not account for OBS hedging (OBS items provide a hedge against interest rate changes, similar to during times of crisis ‘systematic benefits of deposit insurance’), and the spread e_ect (interest rate shocks may be di_erent for the asset and liability sides Topic 4B § As discussed, interest rate risk has two components, cash flow risk (covered by repricing model) and market value risk which will be covered by maturity and duration models. pg. 26 § Repricing model relies on book values rather than market values of assets and liabilities. This is a weakness. o If there is an asset and a liability both maturing in 1 year, and one has a cash flow in the middle of the 1-year period, then the bank must refinance/reinvest to fund the asset. Despite having matching maturities, the bank is still subject to interest rate risk; therefore, we need a maturity model. § § § Most countries, FIs report their balance sheets by using ‘book value accounting’ with historical values. Book values may hide the reality of a FI’s balance sheet. Marking to market is the practice of valuing securities at their market value (if they were liquidated at today’s prices). o Marking to market daily will add volatility into balance sheets, so banks report their book values and then estimate how big a problem IR risk might be under certain scenarios. We consider two models o Maturity model o Duration model Maturity Model § Recall, IR risk is caused when 𝑀/ ≠ 𝑀0 , for a FI’s fixed income assets and liabilities: o The market value rises if interest rates fall and vice versa o The longer the maturity the greater the fall or rise in market value caused by interest rate changes. (Change in discount rate compounded) o The fall in the value increases at a diminishing rate the longer the maturity of the securities 2 𝑀/ = h 𝑊/,% 𝑀/,% , %#$ § § § § 4 𝑀0 = h 𝑊0,3 𝑀0,3 3#$ J is the number of assets, K is the number of liabilities 𝑀/ is the weighted average maturity of an FI’s assets 𝑊/,% is the weighting of the jth asset compared to all assets 𝑀/,% is the maturity of the jth asset pg. 27 § § § § For most banks 𝑀/ − 𝑀0 > 0, this is generally how they make a profit. They have longterm fixed-income assets financed by shorter-term liabilities such as deposits. If the value of assets and/or liabilities change, the FI’s equity value will be a_ected as: 𝐸 = 𝐴 − 𝐿 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝐸 = 𝐴 − 𝐿 The net e_ect of changing interest rates depends on the magnitude and sign of the di_erence 𝑀/ − 𝑀0 o If 𝑀/ − 𝑀0 > 0, the FI su_ers from rising interest rates (banks), o If 𝑀/ − 𝑀0 < 0, the FI su_ers from falling interest rates (insurance companies) o If 𝑀/ − 𝑀0 = 0, the FI is ‘immunised’ somewhat. Problems with the maturity model: 1. The cash-flow structure of assets and liabilities may di_er, such that a maturity matched portfolio may not match in the duration of assets and liabilities. 2. The maturity model does not consider the bank’s leverage (assumes same amount of assets and liabilities I think) 3. Implicitly assumes a parallel shift in IR’s for assets and liabilities. Duration Model § § § § Both cash-flow structure di_erences and leverage are addressed by the duration model. This is the weighted-average time to maturity of a series of cash flows using the relative present values of the cash flows as weights. As duration takes into account o (i) the assets or liability’s maturity, as well as o (ii) the timing of all cash flows It is a more complete measure of interest rate sensitivity compared to the maturity gap. Macauley’s Duration § § § § General formula for annual payments: ∑" .#$ 𝑃𝑉. × 𝑡 𝐷= ∑" .#$ 𝑃𝑉. Duration increases with maturity at a decreasing rate due to discounting Duration increases when yield decreases and vice versa. The higher the coupon payment, the lower the duration. pg. 28 § The duration of a zero-coupon bond: 𝐷5 = 𝑀5 o For all other (conventional) bonds D < M. o Intuition: For a zero-coupon bond, duration equals maturity since 100% of its present value is generated by the payment of the face value at maturity § Rare – bonds with no maturity: ‘Consol (perpetuity) bonds’: 𝑀6 = ∞, 𝐷6 = 1 + 7 § Modified Duration = 𝑀𝑎𝑐𝑎𝑢𝑙𝑎𝑦 𝑑𝑢𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛/(1 + 𝑌𝑇𝑀 /𝑛) o YTM = yield to maturity and n is the number of coupons per year. o MD is a linear approximation $ Immunising the whole balance sheet of an FIs 2 4 𝐷/ = h 𝑊/,% 𝐷/,% , 𝐷0 = h 𝑊0,3 𝐷0,3 %#$ 3#$ § 𝑊/ 𝑠𝑢𝑚𝑠 𝑡𝑜 1, 𝑊0 𝑠𝑢𝑚𝑠 𝑡𝑜 1 § Using the duration model, we find 𝛥𝐸 = r−𝐷/ × 𝐴 × $+7 s − r−𝐷0 × 𝐿 × $+7 s 87 87 o There is an assumption here that there are equal interest rate shocks for assets and liabilities. § 0 0 Let 𝛱 = / (a measure of leverage), then (𝐷/ − 𝛱𝐷0 ) = (𝐷/ − / 𝐷0 ) is the leverage adjusted duration gap. HENCE: 𝛥𝐸 = −(𝐷/ − 𝛱𝐷0 ) × 𝐴 × 𝛥𝑅 = −(𝑎𝑑𝑗. 𝑑𝑢𝑟. 𝑔𝑎𝑝) × 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡 𝑠𝑖𝑧𝑒 × 𝐼𝑅 𝑠ℎ𝑜𝑐𝑘 1+𝑅 § Thus the e_ect of interest rate changed on the market value of a FI’s net worth (equity) is composed of three e_ects: 1. The leverage adjusted duration gap 2. The size of the FI’s assets 3. The size of the interest rate shock § APRA requires banks to hold a minimum amount of capital (Equity) against their assets. Thus in order to comply with regulations, the aim of hedging should not be 𝛥𝐸 = 0, but 𝛥(𝐸/𝐴) = 0, thus instead of setting 𝐷/ = 𝛱𝐷0 , banks now need to target 𝐷/ = 𝐷0 . If an FI believes interest rate risk to be too high what should they do? 1. Reduce 𝐷/ (asset substitution) 2. Increase 𝐷0 (liability substitution) 0 3. Change 𝛱 (/, capital structure) 4. Mixture of above § pg. 29 Duration Model Limitations § § § § Can be costly Dynamic problem (time related) Large interest rate changes and convexity Shifts in term structure are unlikely to be parallel Duration and Convexity § § Duration by itself overlooks the curvature of the price-yield curve and is inaccurate when there are large changes in interest rates. This can be captured by measuring the change in the slope of the price-yield curve around a given point. 𝛥𝑃 1 = −𝑀𝐷 × 𝛥𝑅 + 𝐶𝑋 × 𝛥𝑅9 𝑃 2 - 𝑀𝐷 is modified duration - 𝐶𝑋 is the degree of curvature Demand Deposits and Savings Deposits Problem § § Savings and deposits have open-ended maturities. Possible solutions: o Calculate the ‘run-o_’ or turnover characteristic o Assume their duration is 0 o Use a number of quantitative techniques to test the interest sensitivity of demand and savings deposits pg. 30 Topic 5a Loans § Four main types o Commercial and Industrial o Real Estate o Individual o Other Evaluating Loans § § The loan evaluation process can be broadly broken down into: o Screening (who gets a loan) o Pricing (how much should you be charged) o Monitoring The likelihood of repayment (credit worthiness) plays a role in each step, and as such, banks spend a lot of resources trying to estimate credit risk. Credit Quality Problems § § Poor credit quality assessment often results in non-performing loans which can damage the loan portfolio of a bank. There is a long history of credit quality problems including the subprime mortgage crisis. The Contractually Promised Return on a Loan The Contractually Promised Return on a Loan is influenced by: 1. Interest rate 2. Loan fees 3. Credit risk premium 4. Collateral 5. Other non-price terms (reserve requirements) § § Let’s start with a reference rate (e.g. prime, LIBOR, EURIBOR, 3-month treasury bill rate) and then adjust credit risk. 𝑘=𝐵𝑅+𝑚 o Where 𝑘 is the return on the loan, 𝐵𝑅 is the base rate, 𝑚 is the credit-risk premium (margin) o Each firm will have an associated 𝑚. There are three categories for fees and charges: pg. 31 1. (𝑓), the origination fee expressed as a percentage of the loan 2. (𝑏), the compensating balance, the amount of the loan that the bank holds, expressed as a percentage of the loan (like collateral) 3. (𝑅𝑅), the reserve requirement, the percentage of the deposit that is required to be held with the central bank § § If the loan was for an amount 𝐿𝐴, then as far as the bank is concerned, the amount lent is really 𝐿𝐴(1 − 𝑏) as 𝑏% is held by the bank on deposit paying 0%. Of this amount 𝑅𝑅% is to be placed with the FED earning no interest, thus the amount lent is e_ectively 𝐿𝐴(1 − 𝑏) + 𝐿𝐴 × 𝑏 × 𝑅𝑅 = 𝐿𝐴(1 − 𝑏 + 𝑏 × 𝑅𝑅) From this loan the bank will make 𝐿𝐴(𝑓 + 𝐵𝑅 + 𝑚) Where 𝐵𝑅 is the base rate and 𝑚 is the credit-risk premium § Return will be 𝑘 = 0/($<=+=∗77) = $<=+=∗77 § § 0/(:+57+;) :+57+; o However, f is often a flat fee (not rate) (replace 𝐿𝐴 × 𝑓, by 𝑓𝑙𝑎𝑡 𝑓𝑒𝑒) The Expected Return of a Loan § § The expected return may di_er from the promised return because of default risk. Let 𝑝 be the estimated probability that the promised return on the loan is achieved, i.e. interest and principal repaid. The expected gross return (𝐸(1 + 𝑟))is: :+57+; 𝐸(1 + 𝑟) = 𝑝 + 𝑝 ($<=+=77) = 𝑝(1 + 𝑘) § So the expected return increases linearly with 𝑝 and 𝑚 (probability and credit-risk premium). o In words, charging higher rates of interest is likely to bring about a default. o Also, higher 𝑚 could encourage the borrower to take larger risks in order to make the payment. § If a bank increase 𝑚 there must be an impact on 𝑝. They are non-independent. § Relationship between the promised loan rate and the expected return on a loan (graph): Retail Versus Wholesale Credit Decisions Retail Loans: § § § Higher cost associated with collection of info Smaller dollar size loans Usually a simple accept/reject decision rather than adjustments to the rate o Credit risk controlled through credit rationing pg. 32 o If accepted, standard loan rate is usually charged, § E.g. for mortgages, discrimination via loan to value rather than adjusting rates Wholesale Loans: § § § § Banks use both interest rates and quantity to control wholesale loan risk. 𝑚 > 0 for high risk borrowers, 𝑚 < 0 for low risk borrowers. Higher rate loans are only taken on by firms that have high risk projects (see capm) If the reference rate increases, asset substitution may occur (risk shifting) o This means that it may be wise for banks to ration the amount leant at each level of interest as a way of managing risk. The asset substitution problem highlights the conflicts between stockholders and creditors, for instance, a company could sell a low-risk project and use the proceeds for risky endeavours after a credit analysis has already been performed. Credit Risk Measuring Credit Risk § § § § § Probability of default is best estimated using info on the borrower, there are many alternatives, none are perfect: o At a retail level, credit reports o At a wholesale level, financial statements, annual reports, forecasts, regulatory violations. o Corporate bond market prices capture default probabilities which can be used This information can be used within default risk models. Where can Banks get External Information? o Banks can get external information from credit bureaus; they assemble and distribute the credit history of millions of borrowers. Bureaus use credit scoring systems, most famously the FICO scoring system. FICO includes o Amounts owed (existing debt) 30% weight o Payment history (past credit risk) 35% weight o Length of credit history (past credit exposure) 15% weight o Credit mix (use of past credit) 10% o New credit (recent new credit) 10% NOT allowed to use: o Race, colour, religion, national origin, sex and marital status (Illegal in US) pg. 33 § § § § o Age o Salary, occupation, title, employer, date employed or employment history o Where you live o Any interest rate being charged on a particular credit card or other account o Any items reported as child/family support obligations What important info? o Borrower specific factors § E.g. retail: loan purpose, collateral, age, income § E.g. commercial: leverage, profitability ratios, risk ratios, industry o Industry factors § Real estate price outlook § Mining outlook o Aggregate factors § The business cycle § Level of IRs o What about qualitative information? § E.g. Reputation § Soft information: evaluated in terms of existing relationship Some countries have government run bureaus. US examples: transunion, Equifax, Experian Aus examples: veda, dnb, getcreditscore Default Risk Models § § Quantitative Models - Linear discriminant models, linear probability model, logit/probit model, Cox proportional hazard model. These use past data on loans along with borrower characteristics such as financial ratios to estimate the probability of repayment on new loans. The general form is: " 𝑌 = 𝑃𝐷! = (1 − 𝑝! ) = h 𝛽% 𝑋!,% + 𝜀! PD being probability of default !#$ Linear Discriminant Models § § § These models rank firms' default risk according to their observed characteristics. E.g. the Altman Z function 𝑍 = 1.2𝑋$ + 1.4𝑋9 + 3.3𝑋? + 0.6𝑋@ + 1.0𝑋A Where. - 𝑋$ = 𝑊𝑜𝑟𝑘𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙/𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 pg. 34 § § § - 𝑋9 = 𝑅𝑒𝑡𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑒𝑑 𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑛𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑠/𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 - 𝑋? = 𝐸𝐵𝐼𝑇/𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 - 𝑋@ = 𝑀𝑎𝑟𝑘𝑒𝑡 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑡𝑦/𝑙𝑜𝑛𝑔 𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑚 𝑑𝑒𝑏𝑡 - 𝑋A = 𝑆𝑎𝑙𝑒𝑠/𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 If 𝑍 > 2.99 there is a low risk of default If 𝑍 < 1.81, default risk is high. Between 1.81 and 2,99 is a grey area and the FI has a moderate chance of default Regression Models - Linear Probability Model and Logit/Probit Model § § The dependent variable Y is binary [i.e. equals 0 (not fail/default) or 1 (fail/default)]. The linear probability model can generate negative probabilities and probabilities greater than 1, thus we use a logistic transformation to solve this, known as the § Logit model, $+B "#$% . § Other alternatives include Probit and other variants with nonlinear indicator functions. $ Proportional Hazard (survival) Models § § The dependent variable Y is survival time or time to default which is continuous. The Cox model is the most popular, however, there are many alternatives. Problems with these Models § § § § § § Factors are not always informed by economic theory Factors may change over time No reason to believe that betas (factor loadings) are stable over time Models are linear and without cross terms (assumes no interaction between betas) Ignores qualitative aspects such as reputation risk Usually based on their own historical loan book data which may have an industry or consumer bias. Many models that aim to predict failure fail, an incidence of this is in 2008. From one of the articles on slide 31: Statistical default models, widely used to assess default risk, fail to account for a change in the relations between diPerent variables resulting from an underlying change in agent behaviour. We demonstrate this phenomenon using data on securitized subprime mortgages issued in the period 1997–2006. As the level of securitization increases, lenders have an incentive to originate loans that rate high based on characteristics that are reported to investors, even if other unreported variables imply a lower borrower quality. § § Screening and Pricing climate risk pg. 35 o At loan origination and controlling, especially weakly capitalised lenders, charge higher rates to borrower with a higher impact on the environment o The price of environmental risk in bank lending is driven by local beliefs and regulatory enforcement o China launches Clean Air action in 2013 as a quasi-natural experiment, and what was found was that default rate of high polluting firms rose by 80% along their environmental policy exposure § Quasi: Seemingly; apparently but not really The Term Structure of Credit Risk § § § § With the zero-coupon bond yield curve for corporate bonds (ZCB), we can quickly calculate the probability of default. We define one ZCB yield curve for each rating agency classification, for S&P these are AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB and so on. We can also determine the ZCB curve for government bonds. If the 1 year government ZCB yield is 𝑖 and the 1 year BB corporate bond yield is 𝑘, the risk premium for BB bonds is 𝑘 − 𝑖. Assuming investors are indi_erent to the source of risk adjusted returns (no arbitrage), $+! we can write: 𝑝$,55 (1 + 𝑘) = 1 + 𝑖 → 𝑝$,55 = $+3 o where 𝑝$,55 , is the probability of not defaulting. o This expression assumes a total default (unlikely) Thus, assume that in the case of default, the percentage recoverable (collateral) of the loan return (calculated without default) is 𝜸 o So now we would write: 𝑝$,55 (1 + 𝑘) + (1 − 𝑃$,55 ) × 𝛾(1 + 𝑘) = 1 + 𝑖 and: 𝑝$,55 (1 + 𝑘 − 𝛾(1 + 𝑘)) + 𝛾(1 + 𝑘) = 1+𝑖 § With algebra you get this below: § $+!<C($+3) 𝒊<𝒌 𝑃$,55 = $+3<C($+3) = 𝟏 + 𝟏+𝒌<𝜸(𝟏+𝒌) pg. 36 If the probability of not defaulting in year 1 is 𝑝$,55 and the probability of not defaulting in year 2 is 𝑝9,55 , then the cumulative probability of not defaulting in the first two years is 𝑝$,55 × 𝑝9,55 So the cumulative probability of default is 𝐶𝑝9,55 = 1 − 𝑝$,55 × 𝑝9,55 § Now to find 𝑝9,55 . Let 𝒇𝟏 be the 1-year Gov forward rate for the 2nd period, (1 + 𝑖9 )9 1 + 𝑓$ = (1 + 𝑖$ ) § Let 𝒄𝟏 be the 1-year BB forward rate for the 2nd period, (1 + 𝑘9 )9 1 + 𝑐$ = (1 + 𝑘$ ) § 𝑝$,55 = 1 + § !<3 $+3<C($+3) Therefore, 𝑝9,55 = 1 + :& <6& $+6& <C($+6& ) Instead of bond markets, we could use mortality rates where the probability of defaults is estimated from past data, marginal mortality rates are calculated as: 𝑀𝑀𝑅$ = 𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝐵𝐵 𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑑 𝑑𝑒𝑓𝑎𝑢𝑙𝑡𝑠 𝑖𝑛 𝑦𝑟 1 /𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝐵𝐵 𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑠 𝑜𝑢𝑡𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑖𝑛 𝑦𝑟 1 𝑀𝑀𝑅9 = 𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝐵𝐵 𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑑 𝑑𝑒𝑓𝑎𝑢𝑙𝑡𝑠 𝑖𝑛 𝑦𝑟 2 /𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝐵𝐵 𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑠 𝑜𝑢𝑡𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑖𝑛 𝑦𝑟 2 pg. 37 RAROC § This is the risk adjusted return on capital pioneered by Bankers Trust, 𝑹𝑨𝑹𝑶𝑪 = 𝑶𝒏𝒆 𝒚𝒆𝒂𝒓 𝒏𝒆𝒕 𝒊𝒏𝒄𝒐𝒎𝒆 𝒐𝒏 𝒍𝒐𝒂𝒏 / 𝒍𝒐𝒂𝒏 𝒓𝒊𝒔𝒌 § 𝑂𝑛𝑒 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟 𝑛𝑒𝑡 𝑖𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒 𝑜𝑛 𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑛 = (𝑠𝑝𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑑 + 𝑓𝑒𝑒𝑠) × 𝐿𝑜𝑎𝑛 The loan is approved if RAROC is greater than a benchmark risk adjusted return (often cost), a problem with this is the vagueness of risk measurement. § To estimate loan risk we could use our duration measure (topic 4) 𝜟𝑳𝑵 = −𝑫𝑨 𝑳𝑵 𝟏+𝑹 § o Where 𝛥𝑅 = 𝛥𝐵𝑅 + 𝛥𝑚, if we want to isolate credit risk 𝛥𝑅 = 𝛥𝑚. (m: credit risk component) For 𝜟𝑹 = 𝜟𝒎, if we have historical values for the credit risk premium, then we could: a) Use the most adverse result 𝛥𝑅 = 𝑚𝑎𝑥(𝛥(𝑅! − 𝑅K )) b) Form a probability density and consider the 99th percentile for 𝛥(𝑅! − 𝑅K ) 𝜟𝑹 § 𝛥𝑚 for banks over time is given by the TED spread. 𝑇𝐸𝐷 = 3 𝑚𝑜𝑛𝑡ℎ 𝐿𝐼𝐵𝑂𝑅 − 3 𝑚𝑜𝑛𝑡ℎ 𝑇 − 𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑙 - 𝑘 = 𝐿𝑖𝑏𝑜𝑟 - 𝐵𝑅 = 𝑇 − 𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑙 - 𝑚 = 𝑇𝐸𝐷 § Using the 99th percentile, if standard deviation of risk premium is 0.472%, 𝛥(𝑅! − 𝑅K ) = 0.472 × 2.33 = 1.1%, we use 2.33 (as that is the z score for 0.99) standard deviations as this leaves 1% on each side. § We then substitute 1.1% for 𝛥𝑅 in the equation 𝛥𝐿𝑁 = −𝐷/ 𝐿𝑁 $+7 to find the change in § § 87 loan value for this unlikely event. (OFTEN IN THIS QUESTION YOU IGNORE -D, LOOK AT TUTORIAL 6) Then substitute 𝛥𝐿𝑁 for 𝐿𝑜𝑎𝑛 𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑘 in 𝑅𝐴𝑅𝑂𝐶 = 𝑂𝑛𝑒 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟 𝑛𝑒𝑡 𝑖𝑛𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑒 𝑜𝑛 𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑛 / 𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑛 𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑘 o Approving the loan if this risk adjusted return is greater than some benchmark. Under some circumstances 𝑚 = 𝑅! − 𝑅K is not greater than 0. This occurs when government issued securities are not risk free and are less financially sound than corporations which issue bonds at lower rates. pg. 38 𝑶𝒏𝒆 𝒚𝒆𝒂𝒓 𝒏𝒆𝒕 𝒊𝒏𝒄𝒐𝒎𝒆 𝒐𝒏 𝒍𝒐𝒂𝒏 § Using duration to calculate risk, 𝑹𝑨𝑹𝑶𝑪 = (<𝑫𝒖𝒓𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏×𝑳𝒐𝒂𝒏×𝜟𝒎/(𝟏+𝑹)) § To make a loan below the benchmark bankable, we can 1. Increase net income on loan (however, also increases risk) 2. Reduce loan risk (what is focused on) Option Models of Default Risk § This uses option pricing methods to evaluate the option (probability) to default. § Where the asset value determines the payo_ to stock and debt holders. If the asset value is less than the value of liabilities (debt), the company defaults. Distance to default: pg. 39 Topic 5b Simple Models of Loan Concentration Risk Migration Analysis § § Rating of loan pools and certain sectors are tracked, if loan rating deteriorates faster than historical experience, you will curtail lending. Essentially you create a transition matrix of loan ratings for a certain industry or region etc using historical data, and if more loan ratings deteriorate than historically, you know that the industry/region isn’t doing well, thus you will reduce future lending. Concentration Limits Approach External limits set on the maximum loan size to individual borrowers. The Dodd-Frank measure would impose a 15% concentration limit to other financial firms to prevent a domino e_ect if one were to default. 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑐𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑙𝑖𝑚𝑖𝑡 = 𝑚𝑎𝑥 𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠 𝑎𝑠 𝑎 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑎𝑔𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 × 1/𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑒 E.g a bank’s maximus loss tolerated is 8%, loans in the software industry have an estimated loss rate of 30%, 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑐𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑙𝑖𝑚𝑖𝑡 = 0.08 × 1/0.3 = 26.67% § § Loan Volume Based Models § § § Ingredients (historical data): 1. Market benchmarks (portfolio allocations) 2. FI’s individual loan portfolio allocations Deviations from the market portfolio benchmark indicate the relative degree of loan concentration. Data can be gathered from reports to the central bank, data shared on national credit. This model assumes the benchmark is ideal. Bank A deviation: (TUTORIAL 7) 𝑆𝐷 = 𝑠𝑞𝑟𝑡(1/4 × ((65 − 45)9 + (20 − 30)9 + (10 − 15)9 + (5 − 10)9 )) = 11.73% Where: σ = standard deviation of bank’s jth asset allocation j proportions from the national benchmark, X = asset allocation proportions of the jth bank, ij X = national asset allocations (MEAN), i N = number of observations or loan categories. pg. 40 Regression Based Models § Ingredients (historical data): 1. FI’s loss rates for certain types of loans (by industry, location or any characteristic) taken from the FI’s loan book. 2. Aggregate loss rate (measure of systematic credit risk). E.g. loss rate from the entire bank portfolio or the entire economy. E.g. Industry loss rate model § Based on historical loan loss ratios for each standardised industry classification (SIC). § Use of time-series regression of quarterly losses: 𝑆𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟𝑎𝑙 𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑠 𝑖𝑛 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑖𝑡ℎ 𝑠𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟/𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑛𝑠 𝑡𝑜 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑖𝑡ℎ 𝑠𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟 = 𝛼 + 𝛽! (𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑛 𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑠/ 𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑛𝑠) Where: 𝛼 = loan loss rate for a sector with no sensitivity to aggregate portfolio losses 𝛽! = systematic loss sensitivity of the ith sector loans to total loans Rather than using the loan losses of your portfolio you could use the total economic losses to see sector i’s sensitivity to economy wide shocks etc. If 𝛽! > 1 you may want to curtail lending for that particular sector. Loan Portfolio Diversification and Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) § § By taking advantage of its size, an FI can diversify large amounts of credit risk, assuming there is less than perfect correlation o Bank’s can optimise risk-adjusted returns by changing asset weights such that their loan portfolio lies on the e_icient frontier (greatest return for a given risk or least risk for a given return). However, this is questionable for a loan portfolio. o In MPT risk is defined as the variance of returns, since loans are not traded often, such is hard to estimate, risk is also hard to estimate and portfolio rebalancing isn’t always possible. pg. 41 KMV Portfolio Manager Model § § § This applies MPT in a sense to the loan portfolio, although many loans have non-traded aspects. The KMV portfolio manager model is unique in that it does not require loan returns to be normally distributed. It is a proprietary model to estimate the value of infrequently traded loans. It estimates the return, risk and correlations between loans in an FI’s loan portfolio Three components o The expected return on a loan to borrower 𝑅! = 𝐴𝐼𝑆! − 𝐸(𝐿! ) = 𝐴𝐼𝑆! − (𝐸𝐷𝐹! × 𝐿𝐺𝐷! ) 𝑅𝑒𝑡𝑢𝑟𝑛 = 𝑎𝑙𝑙 𝑖𝑛 𝑠𝑝𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑑 − 𝑒𝑥𝑝𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑒𝑑 𝑑𝑒𝑓𝑎𝑢𝑙𝑡 𝑓𝑟𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑒𝑛𝑐𝑦 × 𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠 𝑔𝑖𝑣𝑒𝑛 𝑑𝑒𝑓𝑎𝑢𝑙𝑡 o The risk of a loan to borrower 𝜎! = “𝐸𝐷𝐹! (1 − 𝐸𝐷𝐹! ) × 𝐿𝐺𝐷! 𝜎! is the volatility of the loan’s default rate around its expected value times the amount lost given default This model assumes that default is distributed binomially o The correlation of default risk between loans made to borrowers The correlation of default risks between loans made to borrowers i and j (𝜌!" ) is the correlation between the systematic return components (𝛽! 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝛽" ) of the ith and jth borrowers’ asset returns. Where 𝑅! = 𝛼 + 𝛽! (𝑚𝑎𝑟𝑘𝑒𝑡 𝑓𝑎𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟) Credit Metrics § Tries to answer this question “If next year is a bad year, how much will I lose on my loans and loan portfolio?” § VaR: Quantifies the extent of possible financial losses within a firm, portfolio, or position over a specific time frame. Used often by investment and commercial banks to determine the extent and probabilities of potential losses in their institutional portfolios. 𝑽𝒂𝑹 = 𝑷 × 𝟏. 𝟔𝟓 × 𝝈 Neither 𝑃, nor 𝜎 observed. Calculated using: o Data on borrower’s credit rating; o Rating transition matrix (one year); o Recovery rates on defaulted loans; o Yield spreads. § § pg. 42 § § § Rating Migration (transition) 1-year transition matrix for a loan currently rated at BBB (Imageà) (Image Below) 𝑟$,& and 𝑠',& for a certain credit rating in 1 years’ time. § So the value is just the probability weighted (Image Above) values of the current values of the loans for each scenario If we have all this info then we should be able to construct the probability density for the loan’s value (fig 12a-1). We may need to do a little smoothing, or model the distribution, or just work with the discrete distribution § Topic 6 Regulation § § ‘A bank’s capital can be viewed as evidence of the willingness of shareholders to commit their own funds to a bank on a permanent basis, as interest free resources and, ultimately, as a cushion to absorb possible future losses.’ RBA Basically, capital serves 2 purposes (Initial OVERVIEW à) o Increases skin in the game for banks § i.e. more to lose in failure § Thus it might reduce the moral hazard problems with insurance pg. 43 § § § o Bu_ers against unexpected losses Evolution of capital regulation o Simple leverage ratio o Basel I: risk-weighted capital-to-assets ratio v 1.0 § Inclusion of OBS credit risk o Basel II: risk-weighted capital-to-assets ratio v 2.0 § Plus add-on for market risk (VaR) § Plus add-on for operational risk o Basel III: risk-weighted capital-to-assets ratio v 3.0 § Plus simple leverage ratio § Plus add-on for market risk (ES) § Plus add-on for operational risk § Plus LCR § Plus NSFR § Plus add-on for interest rate risk (maybe for Basel IV) Today Basel Proposed by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in 1988 o G8 + Switzerland and Luxembourg Leverage (capital) Ratio § Regulators typically target something that looks ( like: 𝐿 = )'( '( § o E is book value of core capital o Historically about 5% Problems with leverage ratio: o Market value may not be adequately reflected by leverage ratio o O_-balance-sheet activities escape capital requirements pg. 44 § o Ratio fails to reflect di_erences in credit & interest rate risks Banks would hide assets o_ the balance sheet and they would try and increase their return by substituting safe assets for risker ones (regulatory arbitrage) Basel 1 Risk weighted capital-to-assets ratio v1.0 o Inclusion of OBS credit risk o Credit assets are now risk adjusted § Full implementation in January 1992 (1993 in Australia). § Initially, capital requirements against credit risk exposures only. o Since 1998: additional capital requirements for market risk exposures. 𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝒓𝒊𝒔𝒌 𝒃𝒂𝒔𝒆𝒅 𝒄𝒂𝒑𝒊𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝒓𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒐 = 𝑻𝒊𝒆𝒓 𝟏 (𝒄𝒐𝒓𝒆) 𝒄𝒂𝒑𝒊𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝒓𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒐 = § § § § 𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝒄𝒂𝒑𝒊𝒕𝒂𝒍 ≥ 𝟖% 𝒄𝒓𝒆𝒅𝒊𝒕 𝒓𝒊𝒔𝒌 𝒂𝒅𝒋𝒖𝒔𝒕𝒆𝒅 𝒂𝒔𝒔𝒆𝒕𝒔 𝑻𝒊𝒆𝒓 𝟏 𝒄𝒐𝒓𝒆 𝒄𝒂𝒑𝒊𝒕𝒂𝒍 ≥ 𝟒% 𝒄𝒓𝒆𝒅𝒊𝒕 𝒓𝒊𝒔𝒌 𝒂𝒅𝒋𝒖𝒔𝒕𝒆𝒅 𝒂𝒔𝒔𝒆𝒕𝒔 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 = 𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑟 1 + 𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑟 2 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑇𝑖𝑒𝑟 1 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 = 𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑇𝑖𝑒𝑟 2 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 = 𝑠𝑢𝑝𝑝𝑙𝑒𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑎𝑟𝑦 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 Assets were subdivided into four classes to determine their counterparty credit risk weighting, some examples are included below: o 0% 𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑘 𝑤𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡 - notes, coins, t-bills o 20% 𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑘 𝑤𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡 - claims on international banking organisations pg. 45 o 50% 𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑘 𝑤𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡 - loans fully secured by mortgage o 100% 𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑘 𝑤𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡 - claims on commercial companies § Calculating Risk Weight: * h 𝑤! 𝑎! !+, Where: wi = risk-weight of ith asset, where i = 1 to n, ai = dollar (book) value of the ith asset on the balance sheet. § Treatment of OBS activities: o Conversion factors used to convert into credit equivalent amounts – amounts equivalent to an on-balance-sheet item. o Conversion factors used depend on the type of instrument (determined by regulator) o Two-step process: § Derive credit equivalent amounts as product of face value and conversion factor. § Multiply credit equivalent amounts by appropriate risk weights (just like for on balance items). pg. 46 Basel 2 Risk weighted capital-to-assets ratio v2.0 Major criticisms of Basel I: risk-weights dependent on broad categories of borrowers. o Minimum ratios stayed the same, risk-weights changed o Basel I had standardised risk models, Basel II implemented intern risk models, allowing banks to calculate their own risk o Additional capital against operational risk exposures § This was fully implemented in Australia on January 1 2008. Risk weight classes now spanned from 0% to 150% and were dependent on counterparty risk and the credit rating of the counterparty. Risk weightings were as follows: pg. 47 § § § § Risk weights were also added to residential mortgages, dependent on the loan to value ratio, level of mortgage insurance and whether the mortgage is standard or nonstandard. With Basel II there were also two internal ratings based (IRB) approaches. o The foundational approach, where banks estimate the one-year PD (probability of default) and a supervisor determines other risk determinants. o Or the Advanced approach where the bank determines PD, LGD, exposure at default (EAD) and maturity (M). In response to Basel II, banks increased lending to banks, governments and corporations with high credit ratings, allowing them to hold much less equity due to the low risk weightings of their assets. In turn leverage actually increased. Problems with a risk-adjusted capital ratio? o Banks can inflate ratios by § Investing in low risk weight assets § Shifting risk from the balance sheet (eyes of regulator) o At the same time, actual leverage (debt) might be increasing without anyone really noticing (see article “The leverage story banks want to hide” on wattle) § Headline capital ratios 10-12% but equity is 2-4%!!! Basel 3 Risk weighted capital-to-assets ratio v3.0 o The key change was to refocus on core equity capital, and a simple leverage ratio. 𝑇𝑖𝑒𝑟 1 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 ≥ 3% 𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑒𝑥𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑢𝑟𝑒 (𝑜𝑛 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑜𝑓𝑓 𝑏𝑎𝑙𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒 𝑠ℎ𝑒𝑒𝑡 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠) 𝐶𝑜𝑚𝑚𝑜𝑛 𝑒𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑡𝑖𝑒𝑟 1 𝐶𝐸𝑇1 = ≥ 4.5% 𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑘 𝑤𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡𝑒𝑑 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 (CET is common equity tier 1). (LR is leverage ratio) 𝐿𝑅 = Other risk-weighted ratios from Basel II remained, tier 1 capital was increased from 46% 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑘 𝑏𝑎𝑠𝑒𝑑 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜 = 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙/𝑐𝑟𝑒𝑑𝑖𝑡 𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑘 𝑎𝑑𝑗𝑢𝑠𝑡𝑒𝑑 𝑎𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 ≥ 8% 𝑇𝑖𝑒𝑟 1 (𝑐𝑜𝑟𝑒) 𝑐𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜 = 𝑻𝒊𝒆𝒓 𝟏 𝒄𝒐𝒓𝒆 𝒄𝒂𝒑𝒊𝒕𝒂𝒍/𝒄𝒓𝒆𝒅𝒊𝒕 𝒓𝒊𝒔𝒌 𝒂𝒅𝒋𝒖𝒔𝒕𝒆𝒅 𝒂𝒔𝒔𝒆𝒕𝒔 ≥ 𝟔% § § Other additions: 1. Capital conservation bu_er Common equity must be 4.5% of risk weighted assets, however, Basel III imposed an additional 2.5% bu_er. This meant that if banks had a pg. 48 CET1 ratio between 4.5% and 7% their distributions (i.e. dividends or bonuses) would be limited. - A bank can also increase equity by retaining earnings; that is, not paying dividends and other distributions, paying bonuses etc. - This idea shows up in Basel III under the capital bu_er idea - These retained earnings can be used for increasing provisions: bad loans, loan commitments, law suits, regulatory changes, future acquisitions etc. 2. Countercyclical bu_er This is an extension of the conservation bu_er in which the bu_er can be extended when excess aggregate credit growth is judged to be associated with a build-up of system-wide risk. This has not yet been implemented. (met with only tier 1 equity) 3. Add-ons for systematically important institutions Two concerns were the moral hazard associated with some banks being too big to fail, and the contagion which occurs with the failure of a large institution. Thus Basel III requires such banks to have a greater loss absorbency (higher equity capital). This will range from an additional 1% to 2.5% CET1 depending on the importance of the bank and determined through stress testing. To be considered systematically important the bank must have $250 billion in assets in the US. 4. Stress testing and recapitalisations Banks must go through stress testing, if they are deemed to not have the capital required to stay solvent in a worst case loss scenario they must raise capital and undergo recapitalisation to meet the requirements. Other than raising money, banks can retain earnings to increase equity. § § Regulatory harmonisation within a country is the last part of Basel III which is yet to be implemented. With this banks will face standard capital charge calculations, limiting the use of internal models. The banking industry is lobbying hard against this as it will force a lot of banks to raise more capital. Liquidity Coverage and Net Stable Funding ratios were also introduced. Topic 7 Securitisation Overview § Asset securitisation through the use of OBS subsidiaries played a significant role in the US Sub-prime Crisis pg. 49 § The securities so formed made it di_icult for investors to assess the risk for a few reasons: o The ratings on these securities were based on incorrect/inadequate information on credit worthiness o As the inherent risk in financial assets becomes more di_icult to understand investors tend to rely on ratings. o They also rely on regulators.... who in turn rely on ratings agencies… who relied on the originators… o This trust may have been misplaced. What is (loan) securitisation? § § § Securitization is the packaging and selling of loan assets and other assets backed by securities. o In principle, anything resembling a promise of future payment can be securitized § Even royalties on recordings (David Bowie, Rod Stewart). Original use was to enhance the liquidity of the residential mortgage market. Major forms of asset securitisation: o Asset backed securities (ABS),(POOL OF ASSETS) o Mortgaged backed securities (MBS). (POOL OF Mortgages) o Collateralised mortgage obligations (CMOs), Collateralised MBS o Collateralised debt obligations (CDOs), Di_erent risk collateralised CMO o Collateralised loan obligations (CLOs) (cmo but for company loans) § More diversified as often exposed to varying industries (uncorrelated risk) pg. 50 § § § o A collateralized mortgage obligation, or CMO, is a type of MBS in which mortgages are bundled together and sold as one investment, ordered by maturity and level of risk. o MBS can be CMO or pass throughs NOT evil o Collateralized mortgage obligations and mortgage-backed securities allow interested investors to financially benefit from the mortgage industry without having to buy or sell a home loan. o Allows for (credit) risk transfer and spreading of risk o Alternative source of funds since it expands the investor base o Securities created are tradeable (more liquid) than underlying assets (bank loans) so are more marketable o Cheaper financing since debt is secured against an asset (i.e. loan) US government policy initiatives to provide access to finance for the poor (after great depression, Many programs, example is housing finance: o Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA): The U.S. government backs bonds guaranteed by Ginnie Mae. GNMA does not purchase, package, or sell mortgages but does guarantee their principal and interest payments. o Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA): Fannie Mae purchases mortgages from lenders, then packages them into bonds and resells them to investors. These bonds are guaranteed solely by Fannie Mae and are not direct obligations of the U.S. government. FNMA products carry credit risk. o Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC): Freddie Mac purchases mortgages from lenders, then packages them into bonds and resells them to investors. These bonds are guaranteed solely by Freddie Mac and are not direct obligations of the U.S. government. FHLMC products carry credit risk. Freddie and Fannie are known as Government Sponsored Entities (GSE) Motivations § From a bank’s point of view pg. 51 Securitisation is similar to loans sales Securitisation gets loan of balance sheet and creates cash to use for more loans The motivation for this activity is similar to that of loan sales. Securitisation in an alternative way for a bank to fund its activities and manage risk. o In Australia securitisation accounts for around 2% of total bank funding Motives for FIs to securitise loans o Q: What happens to the risks faced by an FI when it sells securitized loans? o When loans are securitised and sold there are reductions in the risks faced by FIs. These, along with a straight profit, are motivations for the sale: § Profit § Reduction in level/concentration of credit risk (NPL) § Reduction in liquidity risk § Reduction in interest rate risk § Reduction in regulatory risk (reducing RWAs will help meet capital adequacy requirements)] Same motivations exist for loan sales o Banks sell big parts of their loan books to other banks to achieve similar goals § To raise funds and reduce credit risk (NPL), liquidity risk, interest rate risk, regulatory risk o Regulators can also force loan sales in extreme cases § Failure (e.g. FDIC) § Close to failure (e.g. Good Bank-Bad Bank) What will the FI do with the proceeds from securitisations purchased by investors? These answers also form part of the motivation: o originate new loans; § thereby diversifying credit risk by geography/industry; or § to then securitize (originate-to-sell business model) o improve capital adequacy (by altering the mix of assets and thereby changing the total RWAs). o Q: If a FI uses the originate-to-sell business model then what problem can you identify for purchasers? § The delegated monitoring breakdown § Banks pool money and invest, and allows the reduced monitoring costs, assuming they hold the asset, BUT § Screening for borrower risk diminishes as the bank doesn’t care, as they end up selling it tomorrow o o o o § § § pg. 52 The Originate and Sell Model: Moral Hazard § § § § The decoupling of risk from the lending activity allows the market to transfer risk across counterparties—however it also loosens incentives for proper loan processes. Failures in these processes include: poor or fraudulent documentation; poor collateral assessment and management; failure to monitor borrower activity. The loosening of these incentives is seen as an ingredient in the GFC. Banks were meant to initially do initiate and hold, now they sell Credit Default Swaps (CDS) § § § § Essentially insurance on loans CDS: OTC credit derivative CDS are the most widely used type of credit derivative First CDS contract was introduced by JP Morgan in 1997 A credit default swap (CDS) is a financial derivative that allows an investor to swap or oPset their credit risk with that of another investor. To swap the risk of default, the lender buys a CDS from another investor who agrees to reimburse them if the borrower defaults. § § § § § § By mid-2007, the value of the market had ballooned to an estimated $45 trillion Transfer risk from one party to another (similar to letter-of-credit (Example tutorial 8) or insurance) o Can also do a naked short sell CDS contracts CDS contracts are regularly traded Value of a contract fluctuates based on the increasing or decreasing probability that a reference entity will have a credit event. o Price is called the CDS spread Increased probability of such an event would make the contract worth more for the buyer of protection, and worth less for the seller. The market for CDS is OTC and unregulated, and the contracts often get traded so much that it is hard to know who stands at each end of a transaction OF Balance Sheet Subsidiaries § § Securitisation involves taking loans o_ the balance sheet and placing them in o_balance sheet subsidiaries (aka vehicles/entities). These vehicles come in two forms; pg. 53 § o SPV: special purpose vehicle. o SIV: structured investment vehicle. The key one for securitisation is an SPV but let’s look at each of these and see what’s going on The SPV – Special Purpose Vehicle § § § § § § § § § § § An SPV is created by a FI with the sole purpose of issuing new securities The loans (assets) are securitised and the cashflows (from the assets) paid accordingly The SPV has a limited lifespan, it ceases to exist when the last cashflow is paid. Prima facie, the SPV seems like a bank Q: can you see why and why not? The creation of an SPV separates the business decisions (e.g. credit risk and collateral management) and the financing decisions. The SPV is passive and has no purpose beyond the particular securitisation. The SPV is a limited liability ‘firm’ with no independent employees and no physical location. Services are run by a trustee that follows a set of rules. SPVs are not subject to bankruptcy risk/costs because, by design, they cannot fall bankrupt. Q: Why can’t an SPV go bankrupt? (collateral from note issue in trust) ..... Where has this risk gone? (investors) SIV – Structured Investment Vehicle § § § § § Like a SPV, a SIV is created by a FI with the purpose of issuing new securities & make investments Here the debt that finances the loans/securitized assets is commercial paper—and is backed by some of the vehicle’s assets (loans). It is usually very short-term. The SIV does not have a limited lifespan. It buys new assets as old ones mature. Often set-up in zero-tax location (Cayman Islands, Jersey) The SIV looks much more like a bank than an SPV pg. 54 § § § § § SIV isn’t securitisation, but part of shadow banking The SIV looks a lot like a bank but it doesn’t take deposits; it funds the loans through ABCP. o So is not regulated!!!! Unlike the SPV, the SIV does not pass through the loan repayments to the ABCP investors; ABCP investors only receive the cashflows as specified in the ABCP terms (like all debt instruments) The SIV must make the payments to ABCP investors whether the loan payments cover it or not. Q: What is happening here? The SIV may need to use a credit line or loan commitment from the sponsoring bank Vehicles and Rating Agencies § § § § § § § § § The value of a SPV or SIV for an investor depends on the quality of assets in the vehicle. o The less default, refinancing & liquidity risk the higher the quality. As complexity increases in the asset under consideration, investors tend to rely more on ratings. Institutional investors will not invest in low grade instruments The ratings agencies review all the documentation and conduct due diligence in order to generate a rating. There is an ongoing requirement for information on the vehicle in order for a current rating to be available…. And therefore an ongoing risk of inaccuracy. Securitization produces new debt instruments o Bonds are hard to sell (impossible) without a credit rating o Enter the ratings agencies Q: Who pays the rating agency?? Is there a problem here? Q: Does it matter if payment is conditional on the rating? Q: Can you identify the negative impacts of mortgage brokers, rating agencies, and the securitisation process for investors in such products? o See news story: https://www.reuters.com/article/idIN405044326320130206 pg. 55 Pass-through Security (Tutorial 9) § § § § Any one of the borrowers has the potential to default on their loan agreement, or, possibly pay it o_ faster than scheduled (pre-payment risk). Mortgage securitization is typically supported by government agencies who sponsor mortgage backed securities and provide guarantees on the interest and principal payments to security holders. MORTGAGE-BACKED SECURITY (MBS) This mortgage insurance comes at a price. Each security has the same risk-return profile (i.e. identical default and prepayment risk) Prepayment § § Why people prepay o Housing Turnover: decision to move houses. o Refinancing: § Falling interest rates mean existing borrowers have an incentive to refinance at lower rates. § Costs associated with refinancing: • Transaction costs, Recontracting costs, Penalty fees. E_ects of Prepayment o Good news e_ects § Lower market yields increase present value of cash flows. § Principal received sooner. pg. 56 § § o Bad news e_ects § Fewer interest payments in total. § Reinvestment at lower rates. Some investors have particular investment horizons How do you estimate prepayment? o Methods: § Public Securities Association (PSA) approach. • Assumes 0.2 percent per annum in first month, increasing by 0.2 percent per month for first 30 months, until annualized prepayment rate equals 6 percent • Actual outcomes a_ected by relative coupon level, age of mortgage pool, amortization, assumability, size of pool, conventional/non-conventional, location, and demographics of mortgagees. § Other empirical approaches. • FIs estimate prepayment function. • Conditional prepayment rates are modelled as functions of important economic variables. o Actual outcomes a_ected by relative coupon level, age of mortgage pool, amortization, assumability, size of pool, conventional/non-conventional, location, and demographics of mortgagees. • Model should account for idiosyncrasies. • Based on frequency distribution, FIs can calculate expected cash flows and estimate fair yield. § Option pricing approach 𝑃-.//0&123451 = 𝑃6073*8 − 𝑃-29:-.:;9*& 3-&!3* 𝑌-.//0&123451 = 𝑌6073*8 + 𝑌3-&!3* • Option-adjusted spread between pass-throughs and T-bonds should reflect the value of option. • Derivation of option-adjusted spread: ((=> ) ((=> ) ((=> ) & * + 𝑃 = (,@8 @A + (,@8 @A +. . . + (,@8 @A ) ) ) & ) * ) + ) Structuring of Payments by SPV § The SPV can tranche risk to create securities with di_ering characteristics o i.e., Di_ering risk-return profiles o Achieved through the structuring payments o How does it do this? pg. 57 o Remember these securities are just “pieces of paper” with words on them § Change the wording! o Many types of risk to tranche, we will consider prepayment risk and credit/default risk The Collateralized Mortgage Obligation (CMO) § § § § § § A collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) is a financial debt vehicle that was first created in June 1983 by the investment banks Salomon Brothers and First Boston for Freddie Mac. MORTGAGE BACKED SECURITY Legally, a CMO is a special purpose entity (SPE) that is wholly separate from the institution(s) that create it. CMOs are a mortgage-backed bond issued in multiple classes or tranches with di_ering PREPAYMENT RISK. Creation: o Packaging and securitizing whole mortgage loans, or o Placing existing pass-throughs in a trust (oP-balance sheet). Each class has a fixed coupon. Mortgage prepayment protection for di_erent classes (A, B and C): § Class C: high degree, § Class B: average degree, § Class A: low degree/none. o (Cumulative) default risk by class: § Class C: high, § Class B: average, pg. 58 § § § § § § § Class A: low. Class A: o Shortest average life, o Minimum prepayment protection o Potential buyers: savings banks & commercial banks. Class B: o Expected duration of 5–7 years, o Average prepayment protection, o Potential buyers: superannuation funds & life insurance companies. Class C: o Longest average life, o Maximum prepayment protection, o Potential buyers: superannuation funds & insurance companies. The use of three classes enables FIs to attract a wider range of investors. Class Z: o Accrual class, o Payment only occurs if preceding classes have been retired, o Stated coupon, o Has characteristics of zero-coupon bonds and regular bonds. Class R: o Residual CMO class, o Owner has right to residual collateral plus reinvestment income once all other classes have been retired. pg. 59 Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO’s) § § § § The first CDO was issued in 1987 by bankers at now-defunct Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc. for Imperial Savings Association A decade later, CDOs emerged as the fastest growing sector of the asset-backed synthetic securities market. CDOs are an asset-backed bonds issued in multiple classes or tranches with di_ering DEFAULT RISK. CDOs o_ered returns that were sometimes 2-3 percentage points higher than corporate bonds with the same credit rating. § Global CDO Issuance Volume USD billion o 2004 $157.4 o 2005 $251.3 o 2006 $520.6 o 2007 $481.6 o 2008 $61.9 o 2009 $4.2 § Cash CDOs involve a portfolio of cash assets, such as loans, corporate bonds, assetbacked securities or mortgage-backed securities. Ownership of the assets is transferred to the legal entity (known as a special purpose vehicle) issuing the CDOs tranches. Synthetic CDOs do not own cash assets like bonds or loans. Instead, synthetic CDOs gain credit exposure to a portfolio of fixed income assets without owning those assets through the use of credit default swaps § pg. 60 § Can be fully funded, unfunded, partially funded Mortgage-Backed Bond (MBB, Covered Bonds) § § MBBs are bonds collateralised by a pool of assets (Covered bonds). Special features: o On-balance sheet transactions, pg. 61 § § § § o Relationship between cash flows on underlying asset and cash flow on bond is one of collateralisation. MBB bondholders have first claim on FI’s mortgage assets in case of financial distress. Most MBB issues are backed with excess collateral. Problems: o Illiquidity, o Need for over-collateralisation, o Capital adequacy implications. There are significant diPerences between covered bonds and mortgage-backed securities: (i) a covered bond remains on the issuer’s balance sheet; (ii) an investor has recourse against both the issuer and the cover pool; (iii) principal and interest on the covered bond are paid from an issuer’s cash flow; (iv) non-performing assets in the cover pool can be replaced; and (v) guaranteed investment contracts limit the prepayment risk for covered bonds in the event of the issuer’s default Di_erence between covered bonds and mortgage-backed securities: (i) a covered bond remains on the issuer’s balance sheet; (ii) an investor has recourse against both the issuer and the cover pool; (iii) principal and interest on the covered bond are paid from an issuer’s cash flow; (iv) non-performing assets in the cover pool can be replaced; and (v) guaranteed investment contracts limit the prepayment risk for covered bonds in the event of the issuer’s default. Can be direct issuance or spv issuance Mortgage Pass-Through Strips § § § Cash transaction Special type of CMO IO Strips o Owner has claim to the PV of interest only payments: BA BA BA & * ,-. 𝑃BA = (,@:/,D) + (,@:/,D) +. . . + (,@:/,D) * ,-. pg. 62 • • § Discount e_ect. Prepayment e_ect PO Strips: o Bond sold to investors whose cash flows reflect monthly principal payments. EA EA EA & * ,-. 𝑃EA = (,@:/,D) + (,@:/,D) +. . . + (,@:/,D) * ,-. • • Discount e_ect. Prepayment e_ect The IO–PO strip is a classic example of financial engineering. From a given pass-through bond, two new bonds have been created: the first with an upward sloping price–yield curve over some range and the second with a steeply downward sloping price–yield curve over some range. Each class is attractive to di_erent investors and investor segments. The IO is attractive to non-bank FIs and banks as an on-balance-sheet hedging vehicle. The PO is attractive to those financial institutions that wish to increase the interest rate sensitivity of their portfolios, and to investors or traders who wish to take a naked or speculative position regarding the future course of interest rates. This high and complex interest sensitivity has resulted in major traders such as JP Morgan and Merrill Lynch su_ering considerable losses on their investments in these instruments when interest rates moved unexpectedly against them. Topic 8 Issues Covered § What were the causes of the crisis? 1. The sub-prime housing problems 2. Shadow banking and commercial paper markets 3. Securitized banking, interbank and repo markets 4. Liquidity problems Sub Prime Housing Problems Big Picture Causes § § The traditional banking model of originate and retain assets in books to implement a traditional carry trade has essentially disappeared for many reasons. In particular: pg. 63 o the flattening of the yield curve that we have seen in the last few years combined with o increased competition in the financial services industry § led to a reduction in the net interest margin of banks. § which in turn lead to a search for yield. § § § § § § § § In addition, traditional banks, such as Citibank, compete with traditional investment banks (Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers), which face lower regulatory hurdles as nondeposit institutions. Banks had deposit regulations, and tried to reduce risk on balance sheet with synthetic CDO’s to reduce the amount of regulatory capital This has led banks to imaginative solutions in order to bypass regulatory (that is, capital) constraints. o Synthetic CDOs were created to manage regulatory capital! Importantly, it is not that we have not seen this flattening before but This time it combined with a phenomenal real estate bubble o easy capture of yield. Massive expansion in sub-prime lending (How?) o Loan contracts adjusted to allow subprime access § Shorten duration § Refinancing is required • Easy in a rising market o Funded by § Securitized banking (investment banks) § Shadow banking (commercial banks) Lending standards fell! Fraud and predatory lending? pg. 64 Demise of “originate and hold” § § § § The demise of the “originate and hold” banking model led to a collapse in lending standards (Graphs below) This is not surprising: The expertise to do the evaluation, screening and monitoring of loans has been with banks for the last decades (centuries?) This collapse of the standards also came about because banks faced new competitors in many lines of business (not so new in some cases) such as mortgage originators. Did compensation contracts for loan o_icers exacerbate the problem? YES Shadow Banking and Commercial Paper Markets In search of yield and shadow banking § Banks were flush with cash and looking for investment opportunities o Deposits grew strongly at all major banks: Between 2002-2006 § Citi: 10.1%, JPM 14.8% and Bank of America 11.9% o There was a strong expansion of branches pg. 65 § § § § § § § o Remember the model has become one of origination and fee collections (as well as servicing loans.) § The more origination the better. What are banks to do given that they are limited in what they can do as they are regulated deposit institutions? One response: Bypass unpleasant regulation by “shadow banking” such as SIV and other conduits. Structured Investment Vehicles (SIV) o Invented by Citigroup in 1988 o Bankrupt remote SPV that purchased long-term assets and funded these purchases by selling short-term commercial paper or notes § Borrow short, lend long! § Weighted average life of liabilities = 1 year § Weighted average life of assets = 4 years § Highly levered with maturity/liquidity mismatch o Because of this structure, SIVs were considered to be part of the shadow banking system With a Structured Investment Vehicle (SIV), such as the ones Citi was associated with, one can issue paper of short maturity, say at LIBOR minus 20 bp and invest in long term “mortgages" (CDOs) yielding LIBOR plus 20-30 bp. o Then lever up to increases dollar profits. Essentially these SIVs where set up to allow exposure to subprime mortgages with minimal capital requirements. The catch is the SIV needs to refinance frequently. If liquidity in the ABCP dries up the SIV has typically a line of credit with the sponsoring bank that can be tapped if not an implicit (explicit) guarantee to put the assets back to the bank, say Citi, if refinancing proves impossible. SIVs § § It is instructive to look at some of the characteristics of SIVs Lets look at the assets and liabilities pg. 66 § The credit quality of assets was high as rated by the major rating agencies. However, they were holding a lot of real estate risk through CDOs, MBSs etc which wasn’t made extremely clear. Residential and real estate is also very hard to rate. § The reason this became so feasible was due to the explosion of money market funds that were thirsty for short-term high credit quality paper. Rating agencies obliged by assigning high credit ratings to the CDOs, backing this short term issue. § Liquidity Problems ABCP § § § § Many investors in the ABCP were unsophisticated ones who were buying “triple A" securities. o When they discover the nature of the assets held by SIVs they quickly withdrew financing, leaving SIVs tapping on the pre-agreed lines of credit, which further led to a deterioration of banks' balance sheets, already damaged by their direct exposure to real estate. In Summer and Fall (US, June through December) of 2007 the ABCP market collapsed due to growing fears about the US property market (Graph above) SIVs could not refinance themselves So how do you pay o_ your creditors? o Sell assets pg. 67 § o But markets are declining at the same time the banks are trying to sell leading to huge losses and insolvency. As result many of the banks, such as Citi, ended up bringing a lot of these o_-balancesheet liabilities into their balance sheets, which in turn led to a increased need for capital and worsened the adverse selection problem. Demise of Shadow Banks § § § SIVs and other institutions behaving in a similar fashion failed… Shadow banks came out of the shadows Collateral damage o Other healthy banks, fishing from the same pound as shadow banks saw the same downfall o Northern Rock was heavily reliant on the short-term money market for funding Traditional Vs Securitized Banking § Traditional banking o Traditional banking is the business of making and holding loans, with insured demand deposits as the main source of funds. o A traditional-banking run is driven by the withdrawal of deposits § Securitised Banking o Securitized banking is the business of packaging and reselling loans, with repo agreements as the main source of funds. o Securitized-banking run is driven by the withdrawal of repurchase (“repo”) agreements Securitized-banking activities were central to the operations of firms formerly known as “investment banks” (e.g. Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch), but they also play a role at commercial banks, as a supplement to traditional banking activities of firms like Citigroup, J.P. Morgan, and Bank of America § pg. 68 Repo Market § § § § If the bank defaults on the promise to repurchase, then the investor keeps the collateral. Overall size of the repo market may be about $12 trillion compared to the total assets in the U.S. banking system of $10 trillion Historically, collateral was in the form of high quality liquid assets e.g. short-term US treasury bills So…what were banking using as collateral in repo transactions leading into the crisis…??? (CDO etc) Liquidity Problems Interbank § § § § Soon the credit problems in the banking sector led to severe liquidity problems due to counterparty risk o Adverse selection also killed o_ the interbank market LIBOR spreads, a reflection of interbank liquidity fluctuations, widened considerably: Below you have the plot of the 3 month LIBOR over overnight index swap rates (OIS), a measure of future rates for: o US, (LIBOR, over overnight index swap rates) o Euro area (EONIA, Euro Overnight Index Average) and the o UK (SONIA, Sterling Overnight Interbank Average Rate). Or TED spread = LIBOR - T-bill At some point the banks were very reluctant to lend each other (i.e. the interbank market shutdown) as they suspected that some of them faced severe solvency issues: o In addition it soon became clear that some banks were misreporting LIBOR (to Reuters which collects the sample on behalf of the BBA), that is, they were reporting borrowing rates that were lower than the ones that they were actually charged for fear that it may leak and reflect poorly on their credit status. pg. 69 Repo § § § § Uncertain collateral values lead to big hair cuts How did problems in the subprime mortgages cause a systemic event? i.e. A run in the repo market. There were two main factors: o Increased counterpart risk/adverse selection (higher spreads) killed o_ the interbank market o Increased uncertainty about collateral value (higher haircuts/repo rates) killed o_ the repo market To see how the increase in haircuts can drive the banking system to insolvency: o Take as a benchmark a repo market size of, for example, $10 trillion. § With zero haircuts, this is the amount of financing that banks can achieve in the repo markets. § When the weighted average haircut reaches, say, 20 percent, then banks have a shortage of $2 trillion. Topic 9 Silicon Valley Bank – Interest rate risk Due to the large influx of deposits SVB bought long-term government bonds. However, this exposed SVB to an increase interest rate risk on the banking book. As inflation rose the Fed countered it with an increase in interest rates leading to the value of long-term bonds falling. Although SVB would have survived if they held these long-term bonds to maturity, the unrealised losses of the long-term bonds meant that losses would be incurred if they did have to sell them for a loss. In addition the number of uninsured deposits triggered a bank run when SVB announced they were raising equity due to the unrealised losses. pg. 70 Northern Rock – Liquidity Shock (i.e. Bank Run) Fast asset growth (particularly in mortgages), leading to fast liability growth. Northern was limited by number of depositors it could find so they originated securitised notes from their mortgages. Northern Rock generate cash very quickly if the years prior with securitisation (in September their securitised notes were oversubscribed by 2.2x). However, at the time of failure the demand for securitised notes dropped and Northern Rock couldn’t fund their assets. Their assets were short-term, so they had to go to market for financing regularly and went to market at the wrong time. From the diagram above, to balance the fall in securitisation, the best options were: 1. To increase securitised borrowings (Repo) 2. Increase non-secured borrowings (interbank borrowing) Both these options weren’t possible as the markets were shutting down. 3. Lender of last resort, in the end Northern Rock was nationalised despite deposits being insured by the Bank of England during the bank run. Northern Rock was ‘fishing in the same pond at a bad time.’ Continental Illinois – Concentration risk Continental Illinois was growing quickly by making commercial loans, largely to the energy sector and only if there were ‘proven reserves’ of oil other resources. However, regulators policies on loans changed to allowing loans to be given without proof of resources as collateral. pg. 71 Foreign wholesale funding grew. This funding had high interest costs and sacrificed interest margin to reduce branches taking deposits to reduce operating costs. The failure of Penn Square was triggered by economic conditions: oil prices fell, oil back loans fail, non-performing loans increase. Continental had lent $1.1 billion to Penn Square, 3% of continentals total lending and 17% of their energy loans. This accounted for 41% of continental’s losses in the following years. The credit problem of failing oil prices lead to liquidity problems on the liability side as foreign wholesale and uninsured deposits fell: Oil prices fell à non-performing loans à fall in wholesale funding à uninsured deposits fall à bank run. Washington Mutual Bank – Everything goes wrong. Washington largely in mortgage loans and wrote and securitised bad loans. Like Northern Rock, it faced a bad market, but also like Continental had bad assets. The high-risk lending strategies were largely done through the creation of new products. • Hybrid adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs): “interest only” loans – fixed period and then variable rate or refinance (same from as last week – loan-value ratio) • Pick-A-Payment or Option ARMs: “negative amortization” loans – paying o_ the loan is interest only and what is not paid o_ of the interest is added to the principal (so the principal is growing – only possible in growing housing market as the loan-value ratio isn’t growing). • Home Equity Loans: “” – if the value of your house goes up you can use the increase as collateral for more loans. Also to avoid fees for not being able to meet equity (downpayment) requirements on a loan you could take out a second mortgage for the portion or the entirely of the down payment. • Subprime Mortgages – Washington Mutual was targeting subprime mortgages (below 660 FICO score) down to 580. pg. 72 Washington Mutual originated prime loans (retail) and bought mortgages from brokers (wholesale) and from Long Beach Mortgage Company (subprime). Because banks were buy mortgages, brokers had incentives to give mortgages to anybody. In 2006: House prices dropped àMortgage brokers went bankrupt as banks stop buying mortgages à Subprime mortgages go bad à Non-performing loans increase àwholesale securitised funding falls à Bank run (deposits were largely uninsured) pg. 73