The Russian Endgame Handbook -- Ilya Rabinovich -- Revised ed , 2012 -- Mongoose Press -- 9781936277391 -- aaa45717a8033f5f98251d52ea1d2ee9 -- Anna’s Archive

advertisement

I. Rabinovich

THE RUSSIAN ENDGAME

HANDBOOK

Translated and Revised from the 1938 Edition

English translation© 20 1 2 Mongoose Press

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an

information storage and retrieval system, without written

permission from the Publisher.

Publisher: Mongoose Press

1 005 Boylston Street, Suite 324

Newton Highlands, MA 0246 1

info@mongoosepress.com

www. MongoosePress.com

ISBN 978- 1 -936277-39- 1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-936277-4 1 -4 (hardcover)

Library of Congress Control Number 20 1 2943803

Distributed to the trade by National Book Network

custserv@nbnbooks.com, 800-462-6420

For all other sales inquiries please contact the publisher.

Translated by: James Marfia

Editor: Jorge Amador

Layout: Andrey Elkov

Cover Design: Al Dianov

Printed in China

First English edition

098765432 1

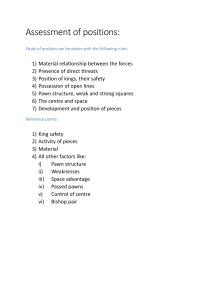

CONTENTS

Editor's Preface

Foreword

Introduction

7

9

11

..................................................................................................

.............................................................................................................

......................................................................................................

CHAPTER 1. The Simplest Mates

A. Mate with the rook

....................................................................

13

.......................................................................................

13

B. Mate with.the queen

18

C. Mate with two bishops . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 9

.....................................................................................

CHAPTER 2. King and Pawn vs. King

A. Winning without the king's help

22

22

B. Winning with the king's help . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

a ) Rook's pawns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

b) Non-rook's pawns

.

26

C. Addendum

.

34

...............................................................

.

.......................................... .........................

.......

...........................................................................

.......................................... ........................................................

CHAPTER 3. Queen vs. Pawn (or Pawns)

.

A. Queen vs. pawn on the seventh rank with the white king out of play

B. Queen vs. pawn o n the seventh rank with a n active white king

...........

..............................................

..

. ............

.......................

a) The rook's pawn

......................................................................................

b) The bishop's pawn

...................................................................................

C. Queen vs. pawn on the sixth

D. Queen vs. pawns

.........................................................................

..........................................................................................

CHAPTER 4. King, Minor Piece, and Pawn vs. King (or King and Pawn)

A. King+ minor piece+ pawn vs. king

a) Knight+ pawn

............

.............................................................

.

............................................................................... ........

b) Bishop+ rook's pawn

.

................................................ .............................

c) Bishop+ knight's pawn

.

................................... .......................................

B. King+ minor piece+ pawn vs. king+ pawn .

................................................

a) Knight+ pawn vs. pawn

........................................................ ............

b ) Bishop+ pawn vs. pawn

...............................................................

CIJ"

DTER 5 . Mate wi"th B1"shop + Kn1"ght

�·

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

CHAPTER 6 . Mate with Knights (vs. Pawns)

A Mate with two knights vs pawn

·

·

............. ........

.........

s: Mate with a single knigh� vs. p ���::::::::::::::::::::

a

.

· · · · · .......

.

.

.....

..........

. ... · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

.

. ....... .......................

· · · ·

.... · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

..............................

.............

37

37

40

40

42

43

44

48

48

48

52

54

54

55

58

71

76

77

91

.. . .

. .

.

96

.

. . ..

. .

96

B. Knight vs. two pawns .................................................................................... 99

C. Bishop vs. pawns

..

1 05

CHAPTER 7. Minor Piece vs. Pawns

A. Knight vs. pawn

.....

.

.............

............

...

.......................

.

...

.....

..

...

..........

.............................................

.

...................

..

...............

........................

.........................................

CHAPTER 8. Exploiting the Adwntage in Endings with a Large Nwnber of Pieces

Aggressively placed pieces

Queenside pawn majority

Open file

...............

.

.................

..............................

.

. .

..

.....

..

....

.

. .. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...................................

.

.

109

109

. 1 13

.....

.............

..........

..

115

Two connected passed pawns

.

117

The meaning of the pawn structure

. .

.

11 9

Mobile pawn center

.

.

. 122

Center vs. wings

.

.

.

. 1 24

Hemmed-in bishop

.

.

:................... 1 25

The exchange (rook vs. minor piece)

. . .

1 27

Extra piece (a piece for pawns)

.

. .

.

133

Rook on the seventh rank................................................................................ 1 36

Passed pawn

.

.

..

.

.

. 1 37

Kingside pawn majority

.

. . ..

1 40

Mobile pawn chain

. . .. . . . . .

141

Isolated d-pawn

.

1 46

Returning an extra pawn

.

.

1 48

Sacrifice of a piece or the exchange ................................................................. 1 50

Gradual siege . .. .

. . ..

.

.

. 1 52

Active defense

...

.

. ..

1 54

........................................................................................................

................................................. ...........

..................................

.......................

..........

.......................

......

........ . . . . . .......

.......

.....................................

. . . . .......

.........

.

..

...

..

...

......

. . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

..

..........

....

.....

CHAPTER 9. Pawn Endings . . .

.. .

. .

.

a) Connected pawns

.

.

....

...........

....

.................

.

.

............. . .

.........

.

. ..

..... .

.

... .

.....

.

..

......

........

...

..........

..

..

.......

.

..

.....

..

.

...

............

.......... . .

.

.

....

............

....

...

.

......

........

............

.

.............

....................

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

..

.

......

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . .

..

.

...................

.........

.

....

.................

.

...

. .

...

.........

........ ...........................

.

..... . . ................

........

.

.....

.

.

.

c) Connected pawns, one of them passed .. .. . ..

d) Connected pawns which are not passed, vs. an immobile pawn

..

1 57

1 57

1 57

1 58

1 59

.. 162

1 62

. 1 66

1 69

1 72

1 72

.................................

b) White's pawns are isolated, and one of them is passed

...

..

..... . ......................

...............

......

............

... . .

. .. . .

........................

................................

.......................

. . ... .

.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...

.................

. . .. .

..........

....

..

........

. ...............................

..........................

.

... . ...

...

..............

......

... . . .

.. . .

.

.

..

................................

.. . ..

.

. . ....

. .. . ..

..

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

c) Doubled pawns

.

B. King + pawn vs. king+ pawn .. ...

.

.

.

.

.

ns

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Passed

paw

a)

.

..

.

.

b) Pawns on the same file

.... . .

.

c) Pawns on neighboring files .

..

.

C. King + two pawns vs. king+ pawn. ...

.. . . .

.. .

a) Two passed pawns vs. one

.....

b) Disconnected pawns

................

........................ . ..............................

..

..

.....................................

.......................................

.............

..

.....................

. . . ............

....................................

. ...

A. King+ two pawns vs. king . . . . ..

....

.................

.........

........................................................

....................

.............

. . . . . ......................

...................................................

................................................

.............

..............

................................

.................... . .

...........

.....................................

.............................................

.................................

....

....

..... . . . .

.....

.

.....

.

...........

. 1 73

1 77

1 85

1 94

.

..............

...............

e) Connected non-passed pawns, vs. a mobile pawn

. ............... . . . .

...

. . . .. .

f) Isolated pawns (none of them passed)

o. Pawn endings with more than three pawns

.

..

..

...........................

......................

a) Making use of the king's active position

b) Exploiting an active pawn stance

.....................

.

...............

E. The king as a defensive piece

F. Stalemate combinations

..

...........

.

......

CHAPTER 10. Bishops of the Same Color

A. Bishop+ pawn vs. bishop

.

.....

.........

.

..........

.

..............

........................................

...............

..

.

..................... ........

...

..

................. . . ......

............

. .

B. Bishop+ two pawns vs. bishop

C. Bishop+ pawn vs. bishop+ pawn

.

D. Same-colored bishops with a large number of pawns

..

.

.. . .

..

.

.

..........

...................................

................

.......

.

.

......................

.

.........................

............................................

..............................

......

.................

.

......

..............

.........

.

....

.................

.......................

.

....

.

.....

.

.......

.

.................

...................................

CHAPTER 11. Bishops of Opposite Colors

.

A. Bishop+ pawn (or bishop+ doubled pawns) vs. bishop

214

220

220

229

237

239

245

245

255

257

260

272

272

B. Bishop+ two connected pawns vs. bishop

. .

273

a) Pawn on the sixth rank

.

.

.

273

b) One pawn on the sixth rank, the other on the fifth .................................. 27 5

c) Pawns on the fifth rank

.

.

.

. 277

d) One pawn on the fifth rank, the other on the fourth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 80

.. . .

e) Pawns on the fourth rank

28 3

f) Less-advanced pawns . .

.

28 5

C. Bishop+ two isolated pawns vs. bishop . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 8 6

D. Endings with more than two pawns . .

.

29 1

........

......................

.

......................

...........................

............................

......

......

.........

..

....... ....... . . ...............................

..

.............. . ....

.....

............... ....................................

..

...

...................................................

... . ...............................................

...

.

.................................

.

........

..

......

.............

......................

......................

CHAPTER 12. Knight Endings .

.

..

.

303

A. Knight+ pawn vs. knight.. . ......................................................................... 303

B. Knight endings with a large number of pawns .

.

. .

306

.............

.........................

..

.

......

..................

......................

..............

...

.... .

CHAPTER 13. Bishop vs. Knight

.

310

A. Endings with a small number of pawns ........................................................ 310

a) "Forcing" pawns

310

b) Exploiting a material advantage ............................................................. 3 1 2

c) Stalemate combinations ......................................................................... 3 1 9

. 323

B. Endings with a large number of pawns

.

. 323

a) Making use of the knight's power

.

.

.......................................... ... . .

....................

...................................................................................

.................................

..............

.....

...

..................

....................................

b) Making use of the bishop's power

.

328

.. . 334

................................................ .......... .

c) Bishop+ rook(s) vs. knight+ rook(s)

CHAPT ER 14. Rook Endings

....

A. Rook+ rook pawn vs. rook

.

.............

.

.................

.

. . .

... . ..

.....

......................

B. Rook + non-rook pawn vs. rook .

..

.

........

.

..................... ...........

.

...

. ..

.................

..

.

...

..

... . ...

......

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. . . .

.....

....

. . . ....

.....

. . . ..

...

....

.. . 337

. . 337

361

. .

.........

............

...

................

..

..

..

a) Black's king stands in front of the pawn

..................................................

b) Black's king is driven away from the pawn

........

.

.....................................

c) Black's king is behind the pawn

............................. .................................

C. Rook+ two pawns vs. pawn

a) Connected pawns

...................................................

b) Disconnected pawns

D. Rook vs. pawns

a) Single pawn

........................................................

..........

.

.

.

...............

.

..... ........................

...................................................................

.............................. ............................................................

...........................................................................................

b) Rook vs. two pawns

...............................................................................

c) Rook vs. three pawns

.

...... . .. . ..... ......... ....... . . ..... ..............

E. Rook+ pawn vs. rook+ pawn

F. Rook+ two pawns vs. rook+ pawn

........................

CHAPTER 15. Queen vs. Rook (or Rook + Pawns)

CHAPTER 16. Queen Endings

.......................

............................................................

G. Rook endings with a large number of pawns

A. Queen+ pawn vs. queen

.

...... ..............................................................

.

.......................

...... ....................................

........................................................................

.............................................................................

B. Queen endings with a large number of pawns

..............................................

CHAPTER 17. Rare Endings

.

362

369

393

404

404

409

417

417

426

436

44 1

447

453

47 1

482

482

484

D. Rook+ knight vs. rook

490

490

498

502

506

Solutions and Answers

509

...................................

A. Rook vs. bishop

...............................................

B. Rook+ bishop vs. rook

C. Rook vs. knight

.

.......................................

..........................................

...............................................................................

................

.

...........................

.

.....

..

......................................

...............................................................................

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . ................. ....................

Editor's Preface

[)ya Rabinovich's classic endgame manual was first published i n the Soviet Un­

n in 1927 and reissued in 1938 under the title of, The Endgame. We present here

io

translated and revised" edition, meaning that we gladly accepted Jim Marfia's

excellent translation of the 1938 Russian text and then made slight alterations to the

voice, to make the final result sound more natural to the mind's ear in our less formal

times, yet without changing the meaning of any statement.

a

"

Although this work was conceived as a teaching aid for group lessons, the indi­

vidual student can make good use of everything in it (except for the foreword). The

book you are holding truly constitutes a complete course on the endgame, assuming

little about the reader's knowledge of the final phase of the game but taking the stu­

dent to a high level of understanding.

For this edition, we have dispensed with the more complex aspects of the author's

discussion of the theory of "corresponding squares, " which we consider to be of

diminishing value in these times of increasingly fast time controls and sudden-death

play. On the other hand, for the reader's convenience we have added many new dia­

grams for the exercises and alternative positions.

7

Foreword

This work is conceived chiefly as a method for advising instructors and teachers

in group learning settings. Since the instructor must deal not only with skilled chess­

players but also with beginners, this book focuses on both elementary and complex

endings, as well as on endings with middlegame features. In laying out the elemen­

tary themes, special attention is paid to the methodical side of the question, and in

our treatment of more complex endings, to the illustration of the latest discoveries

and, where possible, to a fuller elaboration of the theme.

For group study, we recommend the study of separate endgame themes in the

following order. First, study the first five chapters. Then, proceeding to the following

chapters, we recommend that you rely on the "concentric" method of teaching them

- that is, first acquaint your audience only with the basic positions in each chapter,

delaying a deeper study of the given theme to the second ring. The toughest questions

(chapters 9 and 1 4

-

rook and pawn endings, for example) we recommend that you

divide up into three concentric rings.

In order to ensure that each theme is absorbed deeply enough, the instructor

should pay special attention from the very first exercises to the members of the class

learning to analyze independently the simplest positions and then generalizing from

their own experience. Only in these circumstances, "from the particular to the gen­

eral," can you avoid piling up a list of ready-made particular results with no way to

apply the techniques to other situations. T he present volume should present an argu­

ment against such a method of teaching.

This second edition differs from the first not only in eliminating the defects and

flaws that crept in, but chiefly in highlighting the achievements in endgame theory

of the past decade and the ever greater closeness to the needs of the practical game.

With this goal in mind, for example, chapters 8 and 1 4 were reworked and enlarged,

and many of the illustrative games were replaced by new ones, chiefly from interna­

tional practice over the last decade.

In putting together this book, the author also kept in mind those who study end­

ings on their own, and those wishing to refresh or touch up their endgame knowl­

edge. It is precisely for the sake of this rather large group of people, who seek to im­

prove their skills by self-instruction, that this book includes a considerable number

of examples as well as explanatory games.

9

The answers to the examples are given at the end of the book.

I wish to express my gratitude to M.M. Botvinnik, N. D. Grigoriev, G.Y. Lev­

enfish, M. M. Yudovich, A.A. Troitzky, and V.A. Chekhover, as well as to all those

people who, by their efforts and research, collaborated to prepare the second edition

of this work.

IO

Introduction

The most extensively examined part of the game is the endgame; the hardest to

analyze exactly is the opening, and the least comprehensively studied phase is the

middlegame. Endgame theory, in its accuracy, can aspire to bear comparison with

that most fully finished of sciences - mathematics. Opening theory has roughly the

same authenticity as the physical and chemical theories. Middlegame play is the

most complex part of the game, and therefore the least amenable to precise investi­

gation: here, creativity is given the greatest scope.

As we set forth to lay out the best-researched stage - that is, the endgame - we

consider our task to be primarily the connected, systematic presentation of all that

has been given, and to give that presentation the greatest possible level of clarity.

We consider it less important to require that checkmate be given in the fewest

possible moves. Therefore, we will not necessarily seek the shortest path to victory, as

much as the clearest and most easily remembered solution.

11

Chapter 1

The Simplest Mates

(Mate with the rook, the queen, and the two bishops)

The winning plan in all of these end­

ings is the same: The action of your own

pieces (including the king) should be

strengthened as much as possible , while

the enemy king must first be hemmed in,

and then driven into a corner or the edge

of the board. However, you should not

pursue this blindly: hemming in the op­

ponent must be done carefully so as to

avoid stalemate.

Below we see how this is all carried

out i n practice.

A. MATE WITH THE ROOK

Before

all else , you must have in

mind a clear idea of the goal. What is the

position that White wants to achieve?

Generally speaking, is mate possible?

Mate is possible only after the enemy

king has been forced to the edge (or, bet­

ter, to the corner) of the board

.

Such mates are only possible when the

enemy king is "in opposition" - that is,

standing directly opposite the king (on

the same file or rank) , with one square

between them.

In the top half of the diagram, mate

is delivered to the black king standing

in the corner. Here, we don 't need the

white king to be in opposition* such as

at h6. It is enough for the white king to

(See Diagram I)

In the bottom half of the diagram,

the white king has been checkmated in

the middle of the edge line of the board.

• T his kind of o ppos it io n -

tha t is , bot h

kings on t he same fi le , wit h o ne s quare be ­

twee n t hem - is a lso cal le d

"direct opposi­

tion."

13

Chapter 1

We now switch to the general case*.

be located on the sixth rank one knight's

move away from the black king.

3

Now we must answer another ques­

tion: how to drive the opponent's king in

the direction of the edge of the board?

For example, where must the white king

and rook be, in order to force the black

king from d6 to the next-to-last (sev­

enth) rank? Again, the white king must

be in "opposition" (that is, on d4) , and

the rook must give check on the sixth

rank.

2

Here the white pieces are not yet co­

ordinated, and the black king occupies

its best possible position - in the center.

The goal may be achieved in any one

of several different ways. First, we shall

show the "slow, but sure" method, which

works in all cases.

1 .�e8

In order to drive the black king from

the edge square a6 (or h6) to the seventh

rank, it's not necessary for the white

king to be in opposition (that is, on a4

or h4) ; instead, you can occupy the b4

square (or the g4 square) with your king,

a knight's move away from the enemy

king.

This move hems in the enemy king,

not allowing him to get to the right half

of the board - the e-, f-, g-, and h -files.

1 . .. )i;>dS

The black king maneuvers on the d­

file, preferring the center squares (d4, d5) .

2. � g2

To the second question, we can now

give a short answer: in order to drive

the king to the edge, it's enough to give

check at the moment when the kings are

in opposition.

White's first task is to force the black

king to go from the d-file to the c-file ; in

• Us uall y, we shall conside r White to be

the st ronge r side . Th is has noth in g to do with

the gene ral appl icabilit y of o ur con cl usions .

14

The Simplest Mates

order to achieve this, the white king must

approach.

Black's king aims for the center.

1 1 . <JiJe7

2 ... 'litd4 3. 'litf3 'litd5 4. 'ltff4 W d6!

After 4 . . . W d4 (opposition) 5 . l::t d 8+!

Black is driven off the d-file at once.

White places his king, not in opposi­

tion, but a knight 's move away from the

black king, letting his opponent take the

opposition with . . . W c 7 .

5. 'ltt f5 Wd7

ll . . . \t>c5 12. W e6 W c4 13. We5 Wc3

Careful!

Careful!

6. l:Ie l

14. l::td 8 W c4

The rook retreats to the opposite end

ofthe board, as there it is less vulnerable

to attacks.

6 <t>d6 7. l:e2

•••

A move typical in the endgame . The

problem is that the opposition does not

always favor White. It favors White only

when he has the move. (And if White

"took the opposition" with 7. W f6 , then

Black would immediately break the op­

position by 7 . . . W d5 . ) Therefore , White

makes a ''waiting move, " as if inviting

Black to take the opposition himself.

7

••.

W d7

If 1 4 . . . W c2 , White approaches with

the king by 1 5 . W e4; and if 14 . . . <JiJb4,

then White cuts him off from the c-file

by 1 5. I:tc8 .

1 5 . l::td 7!

A waiting move .

15 W c3 16. We4 <JiJc2 17. We3

@cl 18. W e2 Wb2 (or any other move)

19. l::tc7!

•..

Cutting off the c-file.

19 Wb3 20. W d2 Wb4 21. Wd3

<JiJb5 22. W d4 <t>b6

•.•

If 7 . . . W d5 , then 8 . l::td 2+ .

8. W f6 W d8 9. <JiJn

Now Black is forced to take the op­

position, or else go to the c-file himself.

Either way, White moves his rook to d2.

9 ... \t.>d7 10. l::td2+ ! W c6!

On 22 . . . W a6 , the simplest is 23.

\t> c5 ! , and mate next move.

23. l:Icl Wb7 24. Wd5 \t>b6 25. l:c2!

Wb7 26. <JiJd6 Wb8 27. Wd7 'litb7!

If 27 . . . \t.>a7, then instead of the rou­

tine continuation 28. l:b2 White could

play 28. Wc7! W a6 29. l:c5! , and mate

15

Chapter 1

next move. The closer we get to the end,

the more possibilities there are!

is frequently possible , and it shortens the

solution considerably.

1 . J:t e8 'it> dS

28. l::tb 2+

And here we could shorten the end

considerably by playing 28. l::t c6! ; on

Black's best reply, 28 . . . Wb8!, we have

mate on move 32.

The first moves are the same as be­

fore.

2. W g2 W d4 3. Wf3 W dS 4. W f4

W d6

I leave it to the reader to check this.

28 W a6 29. Wc7 @ as 30 . Wc6

W a4 3 1 . @ cs Wa3 32. l::tb 8 Wa2 (for

example) 33. W c4 Wa3 34. l::tb 7! Wa2

3S. W c3 Wal 36. Wc2

. •.

Of course not 36. l::t h 2? , stalemate.

36 W a2 37. l::ta7#

••.

The sole drawback of this system is

the fact that there are too many moves

(37 moves is not too far from 50

the

maximum number of moves for this type

of ending)* . Some notes to condense the

solution are given in the notes to moves

27 and 2 8 . However, we can take this a

step further.

-

For this, we return to the starting

position (WKh 1, WRa8, BKd4), and

try to get to the goal faster. In the above

solution, White irresistibly and steadily

forced Black from the right to the left

and gave mate on the far left file . How­

ever, we shall see that a "change offront"

Up to this point, White has driven

his opponent from right to left; Black

opposed this effort, preferring to leave

the center rather than be driven left onto

the c-file .

The outcome was dragged out in the

above example , because White decided

that, come what may, he was going to

checkmate his opponent on the left edge

of the board. However, with 4 . . W d6 ,

Black has come too close t o the " front"

edge , a8-h8 , and this circumstance

should be exploited immediately.

.

S. l::te S!

Change of front! Why should Black

be driven as before , when the enemy

must be knocked off four positions in all

(the d-, c - , b-, and a-files)? Isn't it bet­

ter to occupy the fifth rank, thereby giv­

ing the opponent only three ranks (the

sixth, seventh, and eighth), instead of

the four he had before?

S W c6 6. W e4

. ••

* Accord ing to t he la ws of chess , if - o ver

t he course of 50 mo ves - a p iece or pa wn has

not bee n capture d a nd no pa wns ha ve move d ,

t he game is a dra w if a player calls it .

16

White's king goes into opposition

with Black's, preparing to check him on

the sixth rank.

The Simplest Mates

6 ... W d6!

If 6 . . . Wb7?, then 7 . l:te6, cutting off

still another rank; while on 6 . . . W b6,

White replies 7. W d4, and if 7 . . . rJdc6,

then 8. l:te6 + , rapidly chasing Black's

king to the next-to-last line (either the

b-file or the seventh rank).

7. Wd4 \ti c6!

If 7 . . . W d7(c7), then 8. rJdcS ! , pre­

venting Black from getting off the next­

to-last line.

8. kte6+

White holds off on his check until

the moment the black king stands in op­

position, since in this position Black will

have to go to the next-to-last line.

10 . . . rJdd7

On 10 . . . rJdb7 , the quickest way to

reach the goal is 1 1 . I:Ic6! (compare the

note to move 28).

1 1 . l:th7+ W e8 12. 'liid 6! 'liif8 13.

'lite6 'litg8 14. llt7!

The strongest - it shortens the solu­

tion by one move.

14 W h8 15. Wf6 W g8 16. rJdg6

rJdh8 17. :C:f8#

•••

Thanks to a new method - the

"change of front" - the solution has

been cut in half! We could have reduced

it by one more move ; however, we think

that for the sake of one little move, it's

not worth burdening the reader's atten­

tion.

8 ... W d7

In reply to 8 . . . W bS , White once

again would rapidly drive Black back to

the left side by 9. l:th6! W b4 1 0. l:tb6 + .

Example 1

-

G. Fahrni :

9. W d5

Stronger than 9. l:th6, when Black

could stretch out the game with 9 . . .

We7!.

In general , the position of the rook,

protected by the king, is very strong, as it

cuts off the black king in two directions.

9 ... W c7 10. l:th6

White mates in 3 moves.

Show that in this position, any rook move

leads to the desired goal.

Now is the time . White offers to let

his opponent take the opposition.

17

Chapter 1

B. MATE WITH THE QUEEN

Like the rook, the queen can only

give checkmate after driving the oppo­

nent to the edge of the board. Of course,

it is easier for the queen to deliver mate,

since: l ) the number of checkmating

positions has grown ; and: 2) driving the

opponent to the edge of the board offers

no difficulties, as this may be achieved in

many different ways.

The first thing White needs to do is to

set his pieces in attacking formation. The

question of whether to move the queen or

the king first looks immaterial to us. Ifwe

need an extra move to achieve our goal,

this should not faze our reader. Only in so­

called "chess problems" are you required

to give mate in a certain number of moves.

In such cases, this requirement is justified

by the elegance of the author's solution.

1. �g3+ c;tie4 (for example)

Along with the previous mating po­

sitions analogous to the rook mates (for

example, WKdJ, Qgl, BKdl) , one may,

for example, point out the following:

WKdJ, Qd2, BKdl. In both positions,

the white king is located in opposition.

But even this circumstance (king in op­

position) is not required. The position

WKdl, BKeJ, Qd2 shows that one may

give mate also in the case where the

kings are a knight's move apart.

Theory shows us that even with the

unfavorable placement of the attacker's

pieces, only I O moves are needed to force

mate. However, and without getting

into all the "subtleties" of this ending,

anything beyond 1 2 moves will hardly be

necessary.

Black approaches the center.

2. @ g7 @ d4 3. @ f6

Now Black may either go to the c ­

file ( .. . <lftc4/c5 ) , or stay in the center

( . . . W d5/e4) .

We shall look at both of these varia­

tions separately (see Variations I and I I ) .

VARIATION/:

(Black leaves the center)

3 @ c4 (for example) 4. <lfte5

•••

White occupies a central position

willingly given up by his opponent.

4

4 ... 'it> c5

On 4 . . . W b4/b5, White increases the

pressure with 5. @ d5 .

5. � b3

Or 5. �c3 + , driving the king to the

next-to-last file (the b-file ) .

18

The Simplest Mates

5 ... W c6 6. �b4 W c7

If 6 . . . 'litd7, then 7. 'iHb7+ .

7. 'iHb5

The queen follows the retreating

king.

As we can see from the previous solution, we recommend that you give check

only as an exception. O n the whole, in the

endgame (in the great majority of cases)

the gradual siege is more important than

hand-to-hand combat. ( " It's more impor­

tant to cut him off than to attack him.")

Example 2:

7 W d8

•••

On 7 . . . W c 8 , White can give mate in

two moves after 8. '1td6.

8. Vi'b7 W e8 9. W e6 ,

and mate next.

VARIATION II:

(Black refuses to give up the center

without a fight)

In how many moves can White force

mate ?

3 W e4

•••

On 3 . . . c;it d 5 , White can reply with 4.

'iHc3 'lit e4 (or 4 ... W d6 5 . Vi'c4 'litd7 6 .

'iHc5 , etc. ) 5 . °iHd2! 'lit f3 6 . Wf5, etc.

4. °iHd6!

C. MATE WITH 'IWO BISHOPS

Two bishops on neighboring diago­

nals hem the opponent in very much.

In Diagram 5, the black king can only

move about in the triangle a4-a8-e8:

Forcing Black to give up the center.

5

4 W f3

..•

O r 4 . . . W e 3 5 . 'lii f5 W f3 6 . Vj'd2 ! ,

etc.

5. 'iHd4 W el (for example) 6. W f5

®f3 7. 'iHdl! W g3 8. 'iHel 'liih 3! 9. W f4,

and mate next.

19

Chapter 1

And so it is not difficult for White to

hem in the black king. How is he going

to be driven to the side of the board? The

bishops may be compared to two lines of

an army, herding the king in the direc­

tion of the c6-b7-a8 line. The first thing

to do is increase the range of activity of

the bishop standing in the rear - that

is, to try to transfer the bishop at a2 to

the a4-e8 diagonal. However, before we

transfer it, we have to secure the rear

- the a2-g8 diagonal , in other words.

This task is fulfilled by the king. There­

fore the first thing we do is to bring the

king from e l closer to a frontal position,

for example:

1. W d2 \t>b S 2. Wd3 W a4 3. � ill

W b 5 4. � b 3!

The rear gets moving.

4 ... W c6 s. \t>d4

Now White repeats the previous

maneuver.

9. @ e6 @ c7 10. � b S

A breather. White uses i t to place

the bishops in their most favorable po­

sitions - side-by-side.

10 . . . W b7

On 10 . . . @ d 8 , there would follow 11.

�b6 + .

l l . @ d7 @ b 8

Catastrophe draws nearer. Now

White can drop the gradual siege in fa­

vor of a finishing attack.

12. � a6!

After this move, Black has only two

squares at his disposal: b8 and a8.

It's not time for � a4+ yet.

12 . . . 'it> a8 13. @ c6!

5 ... W d7

5 . . . @bS would have simplified

White's task, for instance: 6. @ dS @ as

7. @c5 @ a6 8 . � a4!, etc.

6. @eS!

7. �a4+ is threatened.

" Careful with the turnabouts! " If 13.

@ c7 , then it's stalemate!

13 @ b 8 14. @ b6

•••

The white king has occupied the very

best position possible and freed the bishop on cS: king on b6 and bishop on a6

keep the black king trapped.

6 @e8 7. � cs W d7 8. � a4+!

•••

14 @ a8 15. �b7+ @ b 8 16. � d6#

•••

Black has to retreat. The "triangle "

narrows!

8 ... @d8

20

The Simplest Mates

&ample 3:

positions are as follows: the diagonals

a2-g8 and a3-f8. Black's king will be

driven back to the h l comer. From e7 ,

the bishop redeploys from the a3-f8 di­

agonal to the a l -h8 diagonal. The king

takes over guarding the a3-f8 diagonal

from the rear.

Note 1. If the kings on the board

have only one minor piece (with no

pawns) , then mate is not possible. Two

knights (and no pawns) also cannot force

a mate. On the other hand, knight and

bishop can force a win (see Chapter 5).

What's the strongest move in this

position? On which two adjoining di­

agonals should the bishops be placed?

Should we play 1. Jlb4, 1. .ta3 , 1. JlgS ,

1. .th4, 1. .ta4, 1. Jlb3 , l . Jlg4, or 1.

i.hS?

Answer:

The strongest is l . .tb3 ! . The white

king should be in the rear! The frontal

Note 2. In the presence of pawns

(even if they belong to the weaker side) ,

the note shown above may lose its force.

Thus, for example , two knights (or even

a single knight or bishop) can some­

times force mate if the opponent has a

pawn (or pawns) . For details on this, see

Chapter 6.

21

Chapter 2

King and Pawn vs. King

A. WINNING WITHOUT

THE KING'S HELP

In some positions, the pawn promotes

without the king's assistance.

6

Here, White simply advances his

pawn: I . a5 'it' t7 2. a6 'it' e 7 3 . a7 , and the

pawn promotes. Even if in the starting

position it's Black to move , he cannot

stop the pawn. For example , I . . . 'it't7 2.

a5 'it'e7 3 . a6 'it' d7 4. a7, and wins.

How do you know if the black king

can stop the pawn or not? For this, we

can use the "the rule of the square. "One

side of the square is the path over which

22

the pawn has to travel. Thus, in the ex­

ample above, the pawn must traverse the

path from a4 to a8, so on this side we

construct the square a4-a8-e8-e4. The

question now is whether Black's king

can get inside that square or not. In the

example given, Black's king cannot get

inside that square , even ifhe moves first,

so he loses.

Now let's look at the position WKh I,

pa3, BKg8. If it's White to move in this

position, he will advance the pawn: I .

a4. We now set up the square a4-a8-e8e4. Black can't get inside this square ,

so he loses. But if it's Black to move in

the same position ( WKh l, pa3, BKg8),

then he enters the necessary square

a3-a8-f8-f3 just in time , and draws. In

fact, after l ... W t7 2 . a4 'it' e7 3 . a5 'it' d7

4. a6 'it' c7 5. a7 'it' b 7 , Black picks up

the pawn.

In order to flawlessly make use of the

"rule of the square , " the rule must be

refined. The problem is that if the pawn

hasn't moved since the beginning of the

game (for example, a white pawn at a2

or a black pawn at c7) , it can move two

King and Pawn vs. King

squares on its first move (a2-a4 or ...c7c5) ; we establish the rule of the square

for those pawns that can only move one

5.

square at a time. In the examples given,

a pawn on a2 is just as valuable as a pawn

on a3, which can only advance one

square at a time, and a pawn on c7 is just

as valuable as a pawn on c6.

Therefore, if we need to apply the

rule of the square to a pawn that hasn 't

yet moved, the pawn must be moved (in

our minds) one square forward.

4:

6.

Black to move.

Can Black stop the pawn ?

7.

Since the pawn at a2 hasn't moved

yet, we have to construct, not the square

a2-a8-g8-g2, but the square a3-a8-f8-

f3. In this square Black cannot get in, so

he loses. And in fact, after l...'.tig7 2. a4!

\tiff) 3. a5 We6 4. a6 Wd7 5. a7 , Black

should resign.

Examples 5-12:

Use the rule of the square for the fol­

lowing positions:

23

Chapter 2

8.

11.

9.

12.

IO.

Look at each position separately, and

first assume that it's White to move, and

then with Black to move.

(The aforementioned rule

of the

square is set up for a "clean" board

- that is, if there is nothing else on the

board except both the kings and one

pawn. But if there is something else on

the board besides the kings and a pawn,

then this rule may tum out not to be ap­

plicable.)

For instance, in this position:

24

King and Pawn vs. King

squares, and the pawn is not subject to

immediate danger.

Thus, for example, in the position

below:

with Black to move, Black can reach the

square h3-h8-c8-c3 successfully, but he

still loses! On l . . .�c4, there follows 2. h4.

Now Black must get into the square h4h8-d8-d4. But after 3. h5, Black cannot

get inside the h5-h8-e8-e5 square, since

his own pawn gets in his way! So Black has

to play 3 . . . 'itl xe4, when h5-h6 follows, and

the pawn queens. (Nor does l . . .'itefc4 2. h4

'it>c5 help, since after these moves, Black's

king is outside the h4-h8-d8-d4 square.)

B. WINNING WITH

THE KING'S HELP

Now, let's tum to positions in which

the pawn cannot advance to the promotion

square without help from the king.

In order to give an exhaustive answer

to this question, first let's examine the

rookpawns that is, the a- and h-pawns

- and then tum our attention to the rest

(in other words, the b- , c- , d-, e - , f- ,

and g-pawns) .

-

a) ROOK'S PAWNS*

Here White only wins in those cases

where his king can get to the b7 or b8

White wins if he has the move . The

variation I . a4! 'itl c 5 2. a5 'it'b5 3. a6

shows that White manages to secure

his pawn without worsening the posi­

tion of the king (see Examples 1 3 and

14).

And ifthe b8 square i s inaccessible to

White's king (while, as noted above, the

pawn cannot queen by itself) , then the

game will be a draw. Prove this.

How can Black cut White's king off

from the b8 square? For this, his own king

must either be in the comer (on a8, a7,

b8, or b7), or maneuver on the squares c7

and c8. (With an h-pawn, the black king

should maneuver on the squares h8, h7,

g8, and g7 or on f8 and f7.)

*

In o rde r to simpl i fy the position , we

shall examine on ly the case of the white a ­

pawn ; ou r con clusions a re the same also for

a white h -pawn , and also for Bla ck's rook

pawns.

25

Chapter 2

not necessarily keep him from losing in

this case.

Draw

Draw

I n the diagram on the left, Black

draws easily by heading for the corner at

the first chance. For example:

1 . a4 W b8 2. Wb6 @a8 3. a5 (if 3 .

'3;c7?, then 3 . . . @ a7) 3 ... Wb8 4 . a6

W a8! 5. a7 - stalemate!

In the diagram on the right, Black

maneuvers along the squares fl and f8,

and at the first opportunity heads for the

corner. For example:

In this ending, a lot depends on the

placement of the kings - especially on

the placement of the attacking side's

king. This king should push forward:

it should pave the way for its pawn. As

Grigoriev keenly observed, the king

should not "push the pawn forward, so

much as carry it behind him. " The most

favorable king position is out in front of its

pawn. I n accordance with this, our state­

ment is once again divided into 2 cases:

1 ) the king is in front of its pawn; and 2)

the king is behind or next to its pawn.

1. The king is in front of its pawn

As we have already noted, you must

strive to place your king ahead of the pawn

- the further you can advance your king,

the better! It's not necessary to get too

caught up in this: you must only advance

the king as far as will not put the pawn in

danger. Thus, for example, in the position

1 . h6 'it>f8 2. 'it> h8 (if 2. Wg6, then

2 . . . Wg8!) 2 . . . @f7 3. h7 (or 3. Wh7 @f8)

3 W f8 , and White is stalemated!

••.

b) NON-ROOK'S PAWNS

These pawns - that is, the b-, c-,

d, e-, f-, or g-pawns - are consider­

ably stronger than the rook pawn (in

this ending) . Here the defense grows

more complicated, and in some posi­

tions defeat is unavoidable, even with

the best defense. The maneuver which

secures the draw with the rook pawn

(placing the king on one of the squares

in front of the opponent's pawn) does

26

you should not play 1 . 'iii f6 ? in view of

1 . . . W e 3 . I nstead of 1 . W f6? you need to

bring up the pawn by 1 . f4, and then in

reply to l . . .W d5 advance the king, this

King and Pawn vs. King

way restoring the previous distance of

two steps between king and pawn.

Generally speaking, we may state

that, "if the king is two steps ahead of

its pawn (and the pawn is not immedi­

ately threatened), then it's always a win,

regardless of where the enemy ki ng

stands. " For example, the position

If in this position it's Black to move,

then play proceeds something like this:

t . .. W g6

Black must give up the opposition.

2. W e5! @ f7

lf 2 . . . @ g5, then 3 . f4+ @ g6 4. W e6!

and wins.

3. <i!tf5

White takes the opposition.

3 ... W e7 4. W g6 Wf8

If4 ... @ e6, then 5 . f4.

5. @ f6 @ g8 6. f4

is winning for White, regardless of whose

move it is. Only in the case where the pawn

is captured, then of course the game ends

in a draw - for example, in the position

WKe4, pj2, BKe2, with Black to move. But

in the position WKd4, pj2, Bl(f4, the pawn

is lost even with White to move.

Now White brings his pawn closer,

since in between king and pawn he

maintains in all cases the required dis­

tance of two spaces. The continuation

6. W e 7 W g7 7. f4 W g6 8. W e6! Wg7

9. f5 , etc . , would have made the game

longer.

Let's look at that position more

closely.

6

8

Or 7 . . . 'it>e8 8 . )f;g7.

•••

<i!tf8 7.f5 <i!tg8

8.W e7

and the pawn goes through unmolested

to queen.

Let's return to Diagram 8 and sup­

pose that in this position it's White 's

move.

27

Chapter 2

I. f3

Once again, Black is forced to give up

the opposition, that he isforced to make

a move is fatal for him. If Black could

stand in place, White would achieve

nothing. Such a position, where one is

forced to make an unfavorable move , is

called Zugzwang.

1 . 'iti'e6 (for instance) 2. 'iti'g5! @f7

3. @f5, etc. as we showed above.

.•

Now we have to investigate the posi­

tions in which the king is only one square

ahead of the pawn.

9

Black to move - White wins;

White to move - it's a draw

White's king cannot penetrate for­

ward. So he has to advance the pawn.

4. f4

Now White's king is no longer in

front of the pawn, but next to it, and he

will be unable to go ahead of the pawn in

the future. As we show below (see "The

king is behind or next to its pawn " ) , the

game will end in a draw.

From this we may conclude that if

the king stands immediately (one square)

in front of its pawn, then the win is not

always assured. Here the opposition

plays a large role. In the example under

consideration, White wins only when his

opponent is forced to yield the opposition;

in those cases where it is White who has

to give up the opposition, the game will

end in a draw.

This rule has but one exception.

We'll examine this exceptional circum­

stance in greater detail, and then, after a

brief analysis of the position, "The king

is behind or next to its pawn, " we will

pick up where we left off above .

10

Here the only way White can win is if

it's Black's move, for example: l . . .'iti'g6

2. 'it/e5 @fl 3. @ f5 , etc. If it's White to

move in the starting position, the game

ends in a draw, for instance:

1. 'iti'e4 We6!

Black takes the opposition.

2. @f4 @f6 3. 'it/g4 'iti'g6

28

White wins

King and Pawn vs. King

Here , with the king on the sixth rank

in front of the pawn, the win is always

there, regardless of who's to move ( " re­

gardless of the opposition" ) . If it's Black

to move, he loses immediately, for exam­

ple: l . . .We8 2. Wg7, or l . . .Wg8 2. W e7 .

However, even i n the case where White is

to move in the starting position, the win

is there, regardless of the fact that it is he

who must give up the opposition.

The win is accomplished as follows:

1. W e6

White could also play 1 . �g6 @ g8 2 .

f6, etc.

White cannot win ifhe is to move (that is,

if it's White's move). For instance, if I .

W g5 �g7 2 . f5 � f7 3 , f6 , then 3 . . . W f8 !

(this move will b e explained below - see

Diagram 1 1 ) 4. Wg6 Wg8 5 . f7+ @ f8 ,

after which we have stalemate.

l. @e8 2 . f6!

..

2. The king is behind or next to its pawn

Here White secures the win regard­

less of the fact that his king is next to the

pawn.

2 @f8 3. rT

...

The pawn arrives at the seventh rank

without giving check!

3 ... '>t> g7

Here the winning chances decrease

again. If the king is behind or next to its

pawn, and cannot move out infront ofit, the

game nearly always will end in a draw.

Exceptions are possible only if the

white king is on the sixth rank.

For example, in the following posi­

tion:

Black must abandon the pawn's pro­

motion square.

4. '>t> e7 and White wins.

The combination we mentioned

works only if the king is already on the

sixth rank. In this position:

29

Chapter 2

White wins if it's Black to move: l . . . \ti f8

2. fl (the pawn reaches the seventh rank

without a check!) 2 . . .'tlg7 3. ® e7.

its pawn, then Black will always be able

to get a draw.

11

To give a second example, consider

the following position:

Draw

If it's Black to move in this position,

play proceeds as follows:

White to move (this position could

be reached from the position we just

saw) . Finally, we should remind you of

a position derived from the first two. In

the position below:

1 . '\t>f6!

••

The only move. On 1 . . .'\t>g7 , there

follows 2. 'lt>gS! , while on l . . . © fl , it's 2 .

'\t>f5! . In either case , the white king ends

up in front of its pawn, and Black will

be forced to give up the opposition - in

other words, he must allow the white

king even further forward . .

I f I . .:\it fl?, then 2. \t> f5 ( 2 . 'i!t hS will

also do) and then 3. 'lfte6.

2. rs

Moves by the king would only delay

the inevitable.

Black to move loses, despite the fact that

the white king i s behind the pawn.

But if White's king has not reached

the sixth rank, and cannot get in front of

30

2 'i!t f7

•.•

The simplest way for Black would be

to maneuver so that he has the possibil­

ity oftaking the opposition. Following this

King and Pawn vs. King

rule, Black achieves the draw without

any trouble.

7

••.

@f8 8. 'itif6, stalemate.

12

3 @ g5

.

On 3 , 'iti f4, the simplest is 3 . . . 'iti f6 .

3 'iti g7 !

•••

The only move. Now it is necessary

for Black to take the opposition.

4. f6+ 'itif7 5. wrs

Draw

A moment of great responsibility! Up

to this point, Black could allow himself

a few liberties; but now he has to abide

strictly by the rule, " maneuver so that

you have the chance to take the opposi­

tion."

5 Wf8!

...

Black has to move so that in response

to 6. W e6 , he has 6 . . . @ e 8 , and on 6 .

'it'g6, he can play 6 ... @g8.

Let's suppose that it's Black to move

in this position. He has to be able to an­

swer @g6 by taking the opposition with

. . . @g8. Consequently, the only correct

answer is, once again, l . . .W f8 ! . I nstead

l . . .Wg8 would be a mistake , in view of

2. W g6! W h8 (for instance) 3. W f7 ! ; the

same for l . . .W e 8 , because of 2. Wg6

'itif8 3 . f7 .

An d we need t o keep i n mind the fol­

lowing position:

The moves 5 ... W e8 and 5 ... �g8 lose,

for example 5 . . . W e8 6. W e6! (now it's

White who takes the opposition) 6 . W f8

7 . f7 @g7 8 . rt/e7 .

..

6. rt/e6

If 6. @ e s , then 6 . . . @ f7 ! is manda­

tory. " If the square in front of the pawn

is clear, then it must be occupied. "

6 rt/e8 7. f7+

•..

The pawn reaches the seventh rank

with check a good omen for Black.

-

Here, White wins independently of

whose move it is. For example, if it's

31

Chapter 2

White to move, then l . @ cs @ d8 2.

@ d6! @c8 3 . @ c6 @b8 4. b7.

Putting together all of the above, we

get the following rules:

l . The attacking side's king must

advance asfar as possible, since this goes

along with the pawn's safety.

2. The defending side's king must

strive to occupy a square located imme­

diately in front of the pawn (to cut off

the pawn or to stop it in its tracks) . If

possible, he should take the opposition.

And finally, if this is also not possible,

then the king must be maneuvered so

that he has the possibility of later taking

the opposition.

c.

If the white king is on the sixth,

seventh, or eighth rank in front of its

pawn.

d.

If the white king is located be­

hind or next to its pawn, and that pawn

gets to the seventh rank without a check.

e.

If the white king is located be­

hind the pawn, and the black king does

not manage to occupy one of the defensive

positions noted in point 2.

Examples 13-22:

13.

3. The a-pawn cannot win if: I )

Black's king succeeds in occupying the

a8 square ; 2) with the white king on a7,

the black king is on c8 or c7. Only when

the white king succeeds in occupying

the b8 or b7 square without risk to the

pawn, is it a win.

4. A pawn other than a rook pawn

which is secure from extinction may

force the win only in the following

cases:

Black to move draws.

14.

a.

If the white king is more than

one square ahead of its pawn.

b.

If the king is one square ahead

of its pawn, and the opponent isforced to

give up the opposition.

• These rules a re set up for those cases

when the pawn cannot p romote on its own .

32

Black to move; White wins.

King and Pawn vs. King

15.

Draw. ( "Doubled " o r "tripled "pawns,

and also rook pawns, don 't win!)

17.

1 8.

In Examples 1 6-22 the position must

be evaluated (with White to move, and

with Black to move):

16.

19.

33

Chapter 2

20.

I nvestigate how Black wins in No. 16

after l . . .'itif f3 ? 2. 'ifif h2 ! .

C. ADDENDUM

21.

22.

The positions and examples given

above illustrate well the great importance

of the concept of the "opposition. " This

concept will help you considerably to

orient yourself in pawn endings, and will

decrease to a minimum the amount of

time needed to find the right move. An

especially important concept is the di­

rect (or vertical) opposition. I n addition

to this, we have already seen the horizon­

tal opposition. Some other expressions

are also used, such as simple or distant

opposition.

We can establish more precise defini­

tions of these concepts. Under the gen­

eral concept of the opposition, we shall

include the placement of the kings when

between them there is an odd number of

squares in a single line. As examples, we

point out the following mutual king po­

sitions: f3/f5 , f3/d 3 , f3/d5, f2/f6, f2/b2,

f2/b6, g l jg7, g l /a7, g l /a l , etc. From

this, it is clear that kings in opposition

always stand on squares of the same

color.

If there is just one square between

the kings, then we have simple opposi­

tion; if there are three or five squares

between them, then the opposition is

called distant.

Kings located in direct (vertical) op­

position stand on a line parallel to a l -a8.

Direct horizontal opposition connects

the kings along a line parallel to a l -h l .

34

King and Pawn vs. King

Finally, the opposition is termed diago­

nal if there is an odd number of squares

between the kings on a diagonal line .

In the first of the aforementioned

king positions, the kings stand in "sim­

ple direct" opposition; while in the sec­

ond, they stand in " simple horizontal"

opposition. After that, we have "simple

diagonal, " "distant direct, " " distant di­

agonal, " etc . , opposition. What is seen

most often is "simple direct" opposi­

tion; and this is what we have in mind

when formulating the rules for the sim­

plest of pawn endings (see above) .

Now let us examine a position in

which the kings stand in distant direct

opposition, with White's king placed

next to the pawn.

possible , but erroneous would be either

I . . .'it' d6 (because of 2 . 'it' d4) or l . . .'it' e6

(because of 2. 'it' e4 'it' d6 3 . 'it' d4 'it' c6

4. W c4, after which White 's king gets to

the fifth rank) .

It would be more interesting, ifin the

position presented it were Black to move.

As it turns out, only one move here leads

to Black's goal. In order to discover it,

Black must follow this line of reason­

ing: Where does the white king threaten

to move? To d4 or c4. Consequently, it

follows that Black must play such that

on 2. c;!i d4 he can occupy the d6 square ,

and on 2 . W c4 he can play 2 . . . W c6. This

means that right now he must go to a

square from which he can move to either

d6 or c6 - that is, it's necessary to play

I . . . 'it' c7.

Every other move loses. For example,

if l . . .'it' c6, then 2 . 'it' c4; and if l . . .'it' d6,

there is 2 . 'it' d4; while on 1 . . .'it> e7 , White

answers 2. 'it' c4! followed by 'it'bS.

13

The old proverb, "You should

maneuver so as to retain the possibility

of taking the opposition, " is confirmed

by the example we have just seen.

Draw

Moving the white king forward ac­

complishes nothing: if I . 'it' d4, then

l . . .'it> d6, and on I . 'it' c4 there comes

l . . .'it> c6. And if I . 'it' c2? or I . 'it' d2?,

then Black even has a choice. Black

has to show a little alertness only after

I . 'it> e 3 . The simplest reply to I . 'it' e 3

i s I . . .'it' c6 ; I . . . 'it' c7 o r I . . .'it'e 7 are also

In conclusion, let's look at a position

for whose evaluation these rules are in­

sufficient.

(See Diagram 14)

Here the kings are quite distant from

one another, and their positions make it

impossible to bring the situation under

the heading of any sort of "opposition. "

The most natural move i s 1 . 'it' t2 ,

which i s answered by I . . .'it' e7 . I f now 2 .

35

Chapter 2

23. G . Lolli, 1 763 .

14

White to move

White to move - draw; Black to move loses.

'it> f3 or 2. @ e 3 , then Black replies 2 . . .

W f7 ! and gets a draw as shown i n Dia­

gram 1 3 .

24.

Perhaps some readers will be in­

clined, on the basis of the variations we

have presented, to rate the position in

Diagram 14 as drawn. However, before

aflixing so categorical a stamp, we should

see if there are no other winning tries. It

turns out that, if White does not play so

straightforwardly, then he can win. White

should play I . 'it> g2! 'it>e7 2. 'it>h3! 'it>f6 3 .

'it> h4! , after which Black can resign.

We shall put off the explanation of

such an apparently strange outcome for

a little while. The point is that the expla­

nation of the " mechanism" of this end­

game requires more than the aforemen­

tioned rules: for that one must acquaint

oneself with the "theory of corresponding

squares " (see Chapter 9), which will

help illuminate not only the given, rath­

er simple ending, but also considerably

more complex situations.

Examples 23-25:

36

Evaluate this position.

25.

White to move wins.

Chapter 3

Queen vs . Pawn ( or Pawns )

The queen does not always win

against a pawn. A pawn which has ad­

vanced to the seventh rank often forces

the draw. I n some positions, even a pawn

taking the sixth rank can save the game

even if the opponent has the move .

A. QUEEN vs. PAWN ON THE

SEVENTH RANK, WITH THE

WHITE KING OUT O F PIAY

If the stronger side 's king is far away,

and the pawn has already reached the

seventh rank and does not have to worry

about an immediate death (that is, if it

is supported by its own king) , then the

a - , c-, f-, and h -pawns (the rook's and

bishop's pawns) can force a draw; the

rest of the pawns will lose in the major­

ity of cases.

We begin with the center pawns.

(See Diagram 15)

Here, White manages to paralyze the

opponent's threat ( . . . d2-d l � ) : he can

drive the black king to d 1 .

t . �es+

White to move wins

White could also play I . �b2, para­

lyzing the pawn.

I. .. W d3

Or l . . .W fl (f2) 2. �d4! W e2 3 . �e4+

W f2(fl ) 4. �d3! W e l 5. �e3+.

2. �d5+ W c2

Nor does 2 . . . We2 change things. I f

2 . . . W c3/e 3, Black threatens nothing,

so White can bring his king one square

closer.

3. �c4+ Wb2(bl) 4. �d3!

37

Chapter 3

Slowly but surely, the queen ap­

proaches her goal.

4 ... 'iil c l 5. �c3+ 'iil d l

Forced. Now White brings the king

closer, since nothing threatens it.

In the example we have examined,

White makes it his tum to move. In many

positions, the win is achieved by the op­

posite method: giving the opponent the

move. For example , look at this posi­

tion:

6. 'iil b 7 ! 'iil e2

Once again, Black gets aggressive .

Once again, White must defend himself

against . . . d2-d l � .

7 . �c2

Tying up the pawn. 7 . �e5+ and

7 . � c4+ are also good.

White to move

7 . . . 'iil e l !

If the king retreats to e 3 , then with 8 .

� d l! White effectively stops the pawn,

and may approach with his king unhin­

dered.

8 . . . � e 4 + 'iil fl (fl ) 9 . �d3 'iil e l

1 0 . � e3+ 'iil d l I I. 'iil b 6, etc.

I n the example just presented, it is

not difficult to indicate the basic win­

ning idea: by a system of checks, tied in

with close attacks on the pawn, White

forces his opponent to occupy the square

in front of the pawn, thereby gaining the

time needed to bring his king closer. Such

a gain of time is commonly referred to as

winning a tempo. The opponent's threats

are temporarily paralyzed, and White

makes use of this pause to bring up his

reserves.

38

Here White quickly achieves his

goal by means of a waiting move: l .

!la8 , for example. He gives his oppo­

nent the move, making him run into the

jaws of death. Black has to make a move

which is not good for him, as he is in

Zugzwang. White does not win directly

with I . :as, rather he loses a move in

order to create the most favorable situa­

tion for himself.

As we can see from the above , the

winning methods in these two compara­

ble positions are completely different. In

the first method, we have "won" a tem­

po, while the second method involves

" losing" a move. We also call this latter

method a waiting move, with the aim of

giving the opponent the move.

Returning to queen vs. pawn end­

ings, it's not difficult to see that the

Queen vs. Pawn (or Pawns)

knight pawn ( b- or g-) is just as helpless

in the ending cited as a center pawn. For

instance, in the following position:

With a bishop pawn, Black has a dif­

ferent stalemate combination. For example, in this position:

with 'i+'c3+ White can force Black to

guard the pawn, winning a tempo to

bring up the king.

Black can retreat into the comer without

fearing the loss ofthe pawn.

Rook and bishop pawns enable Black

to save himself by stalemate. For in­

stance, in the position below:

White to move. Draw

after I . . . @a I White cannot have his king

approach, because of stalemate. White

has no other plan, since forcing Black to

head for the comer can only be accom­

plished with the check at b 3 , which we

have already examined.

Even in the position in Diagram 1 6 ,

Black gets a draw, i n spite o f the fact

that his king goes to a less favorable

position. For instance, I . ©b7 'it> d2

2 . 'i+'b2 © d i (of course not 2 . . . 'it> d3 ?

because of 3 . 'i+' c l ) 3 . °i¥d4+ © e2 4.

�c3! (or 4. � f4 © d i ) 4 ... © d l 5.

�d3+ © c l (White now wins a tempo ,

which, however, proves insufficient to

win the game) 6 . W b6 'it> b2 7 . �d2

39

Chapter 3

'it> b l 8 . �b4+ 'it> a2 9. �c3 'it> b l 1 0 .

� b 3 + 'it> a l ! , etc .

And so, if the white king does not suc­

ceed in participating in play, then a pawn

(supported by the king) which has reached

the seventh rank can force a draw if it is

on the a-, c-, f-, or h-files; whereas the b-,

d-, e-, and g-pawns lose.

B. QUEEN vs. PAWN ON THE

SEVENTH RANK WITH AN ACTIVE

WHITE KING

Moving on to positions in which the

white king is closer to the action (and

the black pawn stands, as before, on

the seventh rank) , we need to point out

right away that in some cases the king's

role could be a negative one. An exam­

ple could be the following position by B.

Guretsky- Komitz:

Leaving aside such exceptions, the

white king's increased activity can only

improve his winning chances. Even

in the fight against rook's or bishop's

pawns (on the seventh rank) , a small

improvement in the king's position will

pay dividends.

For greater clarity, we examine each

of these types of pawns separately.

a) THE ROOK'S PAWN

Place the black king on b l , and its

pawn on b2. Let the white queen take

the g2 square. Now the question arises:

where to place the white king, so he can

force the win? For example, we show

that with the white king on aS or on e4,

it's a win with White to move ( Diagrams

1 8 and 19).

18

White to move and win

White to move. Draw

Here , White's king just gets in the

way of giving check on the e-file; nor

can White pin the pawn, either. The

game will end in a draw, despite the fact

that the black pawn is neither a rook's

nor a bishop's pawn!

40

To achieve his goal , White need only

bring his king to b3.

1 . 'it> a4!

The less effective move l . 'it> b4 is just

as strong.

Queen vs. Pawn (or Pawns)

1. .. al�+

Forced, since after l . . .'iit> c l the pawn

is lost, and after l . . .'iit> a l White mates in

two moves.

G. Lolli, 1763

20

2. 'it>b3!

Despite the complete equality of

forces, Black must resign.

D. Ponziani, 1782

White to move and win!

19

Here the white king arrives just in

time to get to the fifth rank with

1. 'it> b6!

The king is already active! Block­

ing the queen, it acquires the ability to

close .

White to move and win

Here, White cannot reach b3, but he

has a more effective combination at his

disposal. Playing l . 'iit> d3 forces mate!

( l ...a l � 2. �c2#).

Now we can give an exhaustive an­

swer to that question: where should the

white king stand in the starting position

to win? It must be where it can reach b3

in two moves, or d3 in one . That means

that White wins with his king on the

following squares: a5, b5 , c 5 , e4, e3 or

e2, not to mention closer squares. Even

with the king at e l it's a win, since after

l . '>t d l 'iit> a l (forced), White mates in

two with 2. � d2 .

1 . .. 'iit> b2 2. 'it> a5 +

Also strong is 2 . W c 5 + .

2 'it' c l

•..

If 2 . . . 'iit> c2, then 3 . �g2 + ; while on

2 . . . W a l , White could repeat the combi­

nation by 3. 'it> b4.

3. � h t + 'it> b2 4. � g2+ Wbl

If4 ... 'iit> b 3(a3 ) , then 5. �g7! followed

by 6. � a l ; or if 4 . . . 'iit> a l , then 5. 'iit> b 4.

5. 'it> a4

Or 5 . Wb4, as in Diagram 1 8 .

41

Chapter 3

Lolli's study shows the following: if the black king stands in front of

the pawn, or is in check, it will have to

lose time on moves that do not make

progress. In Lolli's study, Black must

waste an extra two moves, which White