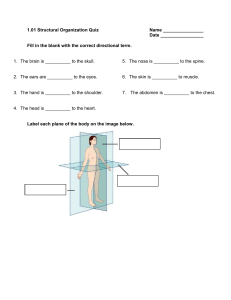

46 CHAPTER Acute Abdomen Alessandra Landmann, Morgan Bonds, Russell Postier OUTLINE Anatomy and Physiology History Physical Examination Laboratory Studies Diagnostic Imaging Diagnostic Laparoscopy Intraabdominal Pressure Monitoring Differential Diagnosis Preparation for Emergency Operation Special Patient Populations Pregnancy Pediatrics Critical Illness Immunocompromised Cardiac Patients Morbidly Obese Elderly Advanced Disease Summary The term acute abdomen refers to the signs and symptoms of abdominal pain and tenderness. This situation often represents an underlying surgical problem that requires prompt diagnosis and surgical treatment. While the ready availability of diagnostic studies such as computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has added greatly to our ability to accurately diagnose most of the conditions responsible for the acute abdomen, the mainstay for diagnosis remains a good history and physical exam complemented by laboratory and radiologic studies as appropriate. In addition, many conditions that are not surgical or even centered in the abdomen can also cause this presentation.1 A prompt and accurate diagnosis is necessary in order to select the appropriate therapy, which may be a laparoscopy or laparotomy. Age, gender, and a history of prior abdominal surgical procedures are associated with different problems causing the acute abdomen. Certain diseases like appendicitis and mesenteric adenitis are more common in the young while biliary tract disease, diverticulitis, and intestinal ischemia are more common in older populations.2 Chapter 67 deals with abdominal pain in children. Numerous problems that are not surgical may also present as an acute abdomen. These include endocrine and metabolic issues, hematologic problems, and disorders caused by toxins or drugs (Box 46.1).3,4 Endocrine and metabolic diagnoses include uremia, diabetic or Addisonian crisis, acute intermittent porphyria, hyperlipoproteinemia, and hereditary Mediterranean fever. Hematologic disorders include sickle cell crisis and acute leukemia. Toxins and drugs that can cause acute abdominal pain are lead and other heavy metal intoxications, narcotic withdrawal, and black widow spider bites. All of these need to be considered when evaluating a patient with sudden onset abdominal pain. The need for prompt surgical treatment of those causes of the acute abdomen that require operation mandates an expeditious evaluation so that the proper therapy can be carried out (Box 46.2). A focused history and physical examination and indicated laboratory and imaging studies will then allow for the correct diagnosis and guide appropriate therapy. While imaging studies have added greatly to the accuracy of the diagnosis of causes of the acute abdomen, a thorough history and careful physical examination remain the mainstays of evaluation. 1134 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY Abdominal pain is visceral, parietal, or referred. The presentation for each helps determine the source of the pain. Visceral pain is vague and localized to the epigastrium, periumbilical region, or lower abdomen, depending on whether it originates from the foregut, midgut, or hindgut. Visceral pain is usually due to the distention of a hollow viscus. Parietal pain is sharper and better localized than visceral pain and corresponds to the nerve roots that supply the peritoneum. Referred pain is perceived at a site distant from the source of the pain. Common sites of referred pain and their sources are listed in Box 46.3. Determining whether the pain is visceral, parietal, or referred can usually be accomplished with a careful history. Whenever bacteria or visceral contents from a perforation are introduced into the peritoneal cavity, an outpouring of fluid from the peritoneal surface ensues. The peritoneum responds to such insults by increasing blood flow, increasing permeability, and forming a fibrinous exudate on its surface. A generalized or localized loss of intestinal motility usually results. Adhesions between loops or bowel, bowl and omentum, or bowel and abdominal wall then occur, which help to localize the inflammatory insult. As a result, an abscess may cause sharp, localized pain but with normal peristalsis whereas a diffuse process such as a duodenal perforation generally results in generalized abdominal pain with absent bowel sounds. CHAPTER 46 Acute Abdomen BOX 46.1 abdomen. Nonsurgical causes of the acute Endocrine and Metabolic Causes Acute intermittent porphyria Addisonian crisis Diabetic crisis Hereditary Mediterranean fever Uremia Hematologic Causes Acute leukemia Sickle cell crisis Toxins and Drugs Black widow spider poisoning Lead poisoning Other heavy metal poisoning Narcotic withdrawal Peritonitis is recognized on physical examination by severe tenderness, with or without rebound tenderness, and guarding. It is due to peritoneal inflammation of any cause. It is usually due to an inflammatory insult, commonly gram-negative infection with either an enteric organism or anaerobe.5 It can also be caused by inflammation that is not due to infection, such as pancreatitis. Another form of peritonitis that occurs in children and is caused by Pneumococcus or hemolytic Streptococcal species and occurs in adults on peritoneal dialysis is called primary peritonitis. The organisms most often seen in the adult, peritoneal dialysis population are Escherichia coli and Klebsiella. HISTORY Despite advances in laboratory studies and imaging, a detailed and focused history is essential to formulating an accurate differential diagnosis in the patient with an acute abdomen. The history should focus on the onset and nature of the pain, any associated symptoms such as nausea or anorexia, whether they began before or after the pain, and the progression of the pain. A history of inflammatory bowel disease, prior abdominal procedures, either open or laparoscopic is important in constructing a differential diagnosis. Often, additional information may be obtained by observing how the patient describes the pain that is experienced. Pain identified with one finger is more localized and typical of parietal innervation or peritoneal inflammation as compared to indicating the area of discomfort with the palm of the hand, which is more typical of the visceral discomfort of bowel or solid organ disease. The intensity and severity of the pain are related to the underlying tissue damage. Sudden onset of excruciating pain suggests conditions such as intestinal perforation or arterial embolization with ischemia, although other conditions, such as biliary colic, can present suddenly as well. Pain that develops and worsens over several hours is typical of conditions of progressive inflammation or infection such as cholecystitis, colitis, or bowel obstruction. The history of progressive worsening versus intermittent pain can help differentiate infectious process from the spasmodic colicky pain associated with bowel obstruction, biliary colic from cystic duct obstruction, or genitourinary obstruction (Fig. 46.1). The location, character, and radiation of the pain are important to elicit. Tissue injury or inflammation can result in visceral and BOX 46.2 conditions. 1135 Surgical acute abdominal Hemorrhage Aortoduodenal fistula after aortic vascular graft Arteriovenous malformation of the gastrointestinal tract Bleeding gastrointestinal diverticulum Hemorrhagic pancreatitis Intestinal ulceration Leaking or ruptured arterial aneurysm Mallory-Weiss syndrome Ruptured ectopic pregnancy Solid organ trauma Spontaneous splenic rupture Infection Appendicitis Cholecystitis Diverticulitis Hepatic abscess Meckel diverticulitis Psoas abscess Ischemia Buerger disease Ischemic colitis Mesenteric thrombosis or embolism Ovarian torsion Strangulated hernia Testicular torsion Obstruction Cecal volvulus Gastrointestinal malignancy Incarcerated hernias Inflammatory bowel disease Intussusception Sigmoid volvulus Small bowel obstruction Perforation Boerhaave syndrome Perforated diverticulum Perforated gastrointestinal cancer Perforated gastrointestinal ulcer somatic pain. Solid organ visceral pain in the abdomen is generalized in the quadrant of the involved organ, such as liver pain across the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Small bowel pain is perceived as poorly localized periumbilical pain, whereas pain from a colonic origin is centered between the umbilicus and pubic symphysis. As inflammation expands to involve the peritoneal surface, parietal nerve fibers from the spine allow for a focal and intense sensation. This combination of innervation is responsible for the classic diffuse periumbilical pain of early appendicitis that later shifts to become an intense focal pain in the right lower abdomen at McBurney point. Further, the pain may also extend well beyond the diseased site. For example, the liver shares some of its innervation with the diaphragm. Thus, liver inflammation may create referred pain to the right shoulder from the C3–C5 nerve roots. Also, genitourinary pain commonly has a radiating pattern. 1136 SECTION X Abdomen Symptoms are primarily in the flank region, originating from the splanchnic nerves of T11–L1, but the pain often radiates to the scrotum or labia via the hypogastric plexus of S2–S4. Determining what factors, if any, worsen or lessen the pain is important. Eating will often worsen the pain of bowel obstruction, biliary colic, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, or bowel perforation. Food can lessen the pain from peptic ulcer disease or gastritis. Patients with peritonitis will avoid any activity that stretches or moves the abdomen. Those patients will describe worsening of the pain with any sudden body movement and realize that there is less pain if their knees are flexed. Anything that causes movement of the abdomen, such as the car ride to the hospital, can be agonizing. Associated symptoms and their timing are important diagnostic clues. Nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, pruritus, melena, hematochezia, and hematuria are all helpful symptoms if present. Vomiting may occur because of severe abdominal pain of any cause or as a result of either mechanical bowel obstruction or ileus. Vomiting is more likely to precede the onset of significant abdominal pain in many nonsurgical conditions, whereas in the Locations and causes of referred pain. BOX 46.3 Left Shoulder Heart Left hemidiaphragm Spleen Tail of pancreas Right Shoulder Gallbladder Liver Right hemidiaphragm Scrotum and Testicles Ureter VISCUS Esophagus, trachea, bronchi Heart and aortic arch SEGMENTAL INNERVATIONS Vagus T1-T3 or T4 NERVES C1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 T1 Sup. cardiac* Middle cardiac Inf. cardiac Stomach T5-T7 Biliary tract T6-T8 Small intestine T8-T10 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kidney T10-L1 9 10 Maj. splanchnic Colon T10-L1 11 Min. splanchnic Uterine fundus T10-L1 12 Least splanchnic Bladder Rectum Thoracic cardiac L1 2 3 4 5 Uterine cervix S2-S4 S1 2 3 4 5 PLEXUSES Sacral Parasympathetic Bladder Cervix Rectum * No known sensory fibers in sympathetic rami. FIG. 46.1 Sensory innervation for viscera. Cardiac Pulmonary* Celiac and adrenal* Renal Spermatic* Ovarian* Preaortic Inf. mesenteric Sup. hypogastric Bladder* Prostate* Uterus CHAPTER 46 Acute Abdomen pain of an acute abdomen with an underlying surgical cause, the pain will precede the vomiting. Constipation or obstipation can be the result of mechanical obstruction or decreased peristalsis. It may either be the primary problem and can be treated with laxatives or prokinetic agents or it may be merely a symptom of an underlying more serious condition. Knowing whether or not the patient continues to pass flatus or have bowel movements is thus important. A complete obstruction, with the absence of flatus or bowel movements is more likely to be associated with subsequent bowel ischemia or perforation caused by the significant distention that can occur. Diarrhea is associated with several conditions that are not treated with operations. These include infectious enteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, or parasitic infections. Bloody diarrhea can be seen in these medical conditions as well as in colonic ischemia. A careful past history can be exceedingly helpful in making the correct diagnosis of the patient with acute abdominal pain. Previous illness or diagnoses can greatly increase or decrease the likelihood of certain conditions that may not otherwise be thought of. For example, patients may report that the current pain is similar to the pain experienced during the passage of a renal stone several years previously. A prior history of appendectomy, pelvic inflammatory disease, or cholecystectomy can significantly limit the differential diagnosis. Any abdominal scars present on the abdomen during the physical exam need to be accounted for in the history that is obtained. Certain medications can both create and mask the symptoms of an acute abdominal condition. High dose narcotics can interfere with bowel motility and lead to obstipation and obstruction. Narcotics can also contribute to spasm of the sphincter of Oddi and exacerbate biliary or pancreatic pain. They can also suppress pain sensations and alter mental status. Both of these impair the ability of the surgeon to diagnose the condition accurately. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs are associated with upper gastrointestinal inflammation and perforation. Steroids can block protective gastric mucous production by chief cells and reduce the inflammatory reaction to infection, including significant peritonitis. The class of agents that are immunosuppressive increase a patient’s risk of acquiring various bacterial or viral illnesses and also blunt the inflammatory response, diminishing the pain that should be present and limiting the overall physiologic response. Anticoagulant drugs use is common in our elderly population and may be the cause of gastrointestinal bleeding, retroperitoneal hemorrhage, or rectus sheath hematomas. They can also complicate the preoperative preparation of the patient and be the cause of substantial morbidity if their use goes unrecognized. Finally, recreational drugs can also be the cause of acute abdominal pain. Cocaine and methamphetamine use can create an intense vasospasm that can cause life-threatening cardiac or intestinal ischemia as well as severe hypertension. The differential diagnosis of the acute abdomen in women includes many more conditions than are found in the male population. In the past, the negative laparotomy or laparoscopy rate in women with acute abdominal pain was significant and substantially higher than that seen in men. Improvements in, and the widespread availability of, advanced imaging such as MRI and CT scans have improved the diagnostic accuracy of the evaluation of acute abdominal pain in this population. A careful gynecologic history remains important in the evaluation of abdominal pain in young women. The likelihood of ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, mittelschmerz, and severe endometriosis are all dependent upon the details elicited in the gynecologic history. 1137 PHYSICAL EXAMINATION The physical examination remains an essential component in the evaluation of the acute abdomen. You will be able to garner valuable information from this step to better inform the next steps in the diagnostic pathway. Physical examination will generate a more precise differential diagnosis, and this will allow for the initiation of necessary therapy in a timely manner. Despite wider availability of advanced diagnostic imaging, it cannot replace an organized and thorough physical examination. The initial evaluation of all patients should begin with general inspection. Information regarding the severity of the illness can quickly be assessed upon walking into the room. Symptoms such as diaphoresis, pallor, dyspnea, and decreased alertness can be assessed rapidly and will forewarn the examiner that a serious issue is at hand. For an acute abdomen, the general inspection will be the first evidence of whether the patient has peritoneal inflammation. These patients tend to be very still as movement aggravates their abdominal pain. In contrast, patients with abdominal pain without peritoneal inflammation will fidget in attempts to find a comfortable position. Inspection of the abdomen is the next step. Attention is focused on the contour of the abdomen and skin abnormalities. Abdominal wall distension occurs in several abdominal processes such as intestinal obstruction, development of ascites, or presence of a growing mass. Surgical scars should be identified and correlated to the history taken prior to the physical examination. Other skin findings, such as erythema or blistering, can alert the examiner to the possibility of soft tissue infections that may require immediate debridement. Ecchymosis can also be an indication of a fascial necrotizing infection; additionally, it may alert the examiner to accidental or nonaccidental trauma and may warrant further social investigation. Historically, the next step in evaluation is auscultation. This maneuver should be done prior to percussion or palpation as bowel activity can be affected by manual manipulation. Vascular abnormalities, such as arterial stenosis or arteriovenous fistulas, can be detected by auscultating bruits within the abdomen. Auscultation for bowel activity is controversial. It has been taught that the quantity and quality of bowel sounds heard correlate with the motility of the bowel. Ileus is associated with hearing fewer than one bowel sounds every 15 seconds per quadrant. Conversely, high-pitched tinkling sounds are associated with mechanical bowel obstruction. Many argue that history of flatus and bowel movements are more accurate at determining whether the patient is having a bowel motility issue than auscultation. A recent review article cited low sensitivity and positive predictive values for auscultating bowel sounds in normal volunteers, patients with bowel obstruction, and patients with postoperative ileus. They also noted poor interobserver reliability for bowel auscultation, recording it at 54%.6 Auscultation can be useful but must be correlated with history and other exam findings. Percussion is capable of eliciting a wealth of information. Dull resonance in the right upper quadrant identifies the liver; measuring the superior-inferior range of this dullness will give the examiner a rough estimate of liver size. Percussion is useful in determining whether abdominal distension is due to excess air or fluid. The presence of localized dullness elsewhere in the abdomen should raise concern for an intraabdominal mass. Tympany, or hyperresonance, is consistent with gas-filled structure deep to the abdominal wall. If tympany is heard in the right upper quadrant, where the liver is located, this indicates there is air between 1138 SECTION X Abdomen Right upper quadrant Liver Gallbladder Duodenum Right kidney Right ureter Right lung/pleura Left upper quadrant Stomach Spleen Pancreas Left kidney Left ureter Left lung/pleura Right lower quadrant Appendix Ileum Right colon Right ureter Bladder Right ovary or testicle Left lower quadrant Sigmoid colon Rectum Left ureter Bladder Left ovary or testicle FIG. 46.2 Abdominal structures by palpations quadrants. the abdominal wall and liver, and intraperitoneal free air should be suspected. Diffuse dullness to percussion raises suspicion for a fluid-filled abdomen. A fluid wave can be created by a quick firm compression of the lateral abdominal wall; a wave should then travel medially across the abdominal wall. Percussion can also be useful identifying the presence of peritonitis. A patient with peritonitis will have exquisite tenderness during percussion of the abdomen and may not be able to withstand the maneuver. Jostling the abdominal viscera by percussing the flank, iliac crest, or the heel of an extended lower extremity will illicit the characteristic signs of peritonitis. These maneuvers are more reliable for detecting inflammation of the peritoneal lining than the historical technique of deep palpation followed by quick withdrawal of pressure and asking whether the pressure or release was most painful. This can be very painful, regardless of the presence of peritonitis, and leaves room for subjective interpretation by the patient. The final portion of the abdominal exam is palpation. Generally, this is the most informative portion of the examination. It provides details that help you localize the source of pain as well as abnormalities within the abdomen. The examiner should begin with superficial palpation away from the area with the most significant pain; superficial palpation allows for assessment of masses or fluid collections anterior to the abdominal wall and whether the pain is associated with these abnormalities. More pressure should then be applied to perform deep palpation. Deep palpation allows the examiner to assess pain from an intraabdominal source as well as the presence of any intraabdominal masses or organomegaly. Diffuse tenderness to palpation suggests extensive inflammation or delayed presentation of an ongoing disease process. Identifying the region of maximum tenderness will give the examiner the likely source of abdominal pain. By identifying the quadrant causing the pain, a differential diagnosis can be developed based on the structures within that quadrant (Fig. 46.2). Guarding can be encountered while performing abdominal palpation. It is necessary to differentiate between voluntary and involuntary guarding. Voluntary guarding occurs when the patient anticipates painful stimuli and tenses their abdominal wall muscles. To prevent this, have the patient lie supine on the exam table and bend his or her legs to place the soles of their feet flat on the bed. Instruct them to take a deep breath while you palpate. These maneuvers result in relaxation of the abdominal wall as well as distracting the attention of the patient, preventing voluntary guarding. If the abdominal wall tenses despite the above techniques, the patient has involuntary guarding which is a sign of peritonitis. There are several named exam maneuvers associated with different disease processes. These can be seen in Table 46.1. Murphy sign for acute cholecystitis which involves deeply palpating the right subcostal region while the patient inspires deeply. If cholecystitis is present, the inspiration will be cut short due to pain as the gallbladder encounters the anterior abdominal wall. The obturator and psoas signs can be useful identifying the relative position of an inflamed appendix. Rovsing sign suggests right lower quadrant peritonitis. CHAPTER 46 Acute Abdomen 1139 TABLE 46.1 Abdominal examination signs. History Danforth sign Shoulder pain on inspiration Hemoperitoneum Inspection Cruveilhier sign Cullen sign Grey Turner sign Ransohoff sign Varicose veins at umbilicus Periumbilical bruising Local areas of discoloration near umbilicus and flanks Yellow discoloration of umbilical region Portal hypertension Hemoperitoneum Acute pancreatitis Ruptured common bile duct Acute appendicitis Bassler sign Blumberg sign Carnett sign Chandelier sign Courvoisier sign Fothergill sign Iliopsoas sign Murphy sign Obturator sign Pain or pressure in epigastrium or anterior chest with persistent firm pressure applied to McBurney point Sharp pain created by compressing appendix between abdominal wall and iliacus Transient abdominal wall rebound tenderness Loss of abdominal tenderness when abdominal wall muscles contracted Extreme pelvic pain with movement of the cervix Palpable gallbladder when jaundice is present Abdominal wall mass that does not cross midline and is palpable when rectus is contracted Elevation of extended leg against resistance is painful Pain caused by inspiration while applying pressure to right upper abdomen Flexion and external rotation of right thigh creates hypogastric pain Rovsing sign ten Horn sign Pain at McBurney point when palpating the left lower quadrant Pain caused by gentle traction of right testicle Palpation Aaron sign Additional exams often provide useful information. Digital rectal exam provides information about hollow viscus bleeding and sources of distal obstruction causing constipation and obstipation. In women, results of pelvic exam will help include or exclude gynecologic sources of lower abdominal pain. A 2014 study found that of 290 women of reproductive age with right lower quadrant pain thought to have acute appendicitis 37 (12.8%) had gynecologic pathology with a normal appendix.7 Pelvic examination may identify this pathology earlier and allow for appropriate counseling prior to surgery. LABORATORY STUDIES Laboratory studies can narrow the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain. Box 46.4 contains a complete list of laboratory tests that can assist the workup an acute abdomen. A complete blood count gives several important data points. The white blood cell count can be elevated or decreased in the setting of an acute abdomen. The best evidence of an acute infection is an elevated absolute number or percentage of band cells, so it is ideal to send for a complete blood cell count with a white blood cell differential. Low hemoglobin and hematocrit alert the care team to a source of bleeding that may be associated with the source of abdominal pain. If the hemoglobin and hematocrit are higher than normal, one should evaluate the patient for signs of dehydration. Patients with abdominal pain should also have a complete metabolic panel sent. Electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, and calcium are evaluated as well as renal function tests such as blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Alterations in these values will alert the physician to fluid losses from diarrhea or vomiting as well as possible endocrine sources of abdominal pain (i.e., hyperparathyroidism). The complete metabolic panel contains “liver function tests” that, when elevated, should lead to further assessment of the hepatic and biliary systems. Viral hepatitis panels should be BOX 46.4 pain. Chronic appendicitis Peritoneal inflammation Intraabdominal source of abdominal pain Pelvic inflammatory disease Periampullary mass Rectus muscle hematoma Retrocecal acute appendicitis Acute cholecystitis Pelvic abscess or inflammatory mass (appendicitis) Acute appendicitis Acute appendicitis Laboratory tests for abdominal • White blood cell count with differential • Hemoglobin • Platelets • Electrolytes • Creatinine and blood urea nitrogen • Amylase and lipase • Total and fractionated serum bilirubin • Serum lactate levels • Viral hepatitis panel • Urinalysis • Urine human chorionic gonadotropin • Clostridium difficile culture and toxin assay sent when a source for elevated liver enzymes cannot be identified. Amylase and lipase are indicated when pancreatitis is a suspected source of abdominal pain. Arterial blood gas with serum lactate measurements are valuable tests when evaluating any severely ill patient. In the setting of the acute abdomen, lactic acidemia is a sign of hypoperfusion and depending on the circumstances raises the concern for mesenteric ischemia. Mesenteric ischemia is a serious condition with significant mortality despite improvements in critical care and can be tricky to diagnose in some patients. Attempts to identify additional markers specific to mesenteric ischemia are underway but not yet available for clinical use.8 Urine studies should be a standard laboratory test sent in a patient with abdominal pain. A urinalysis can give several points of information. The presence of bacteria, white blood cells, and leukocyte esterase in the sample raises concern for a urinary tract 1140 SECTION X Abdomen infection and possibly pyelonephritis; this would account for suprapubic pain or flank pain, respectively. Nephrolithiasis and nephritic syndromes can be detected by noting red blood cells in urine. Casts within the urine should also raise concern for a renal source of abdominal pain. Finally, in women of childbearing age, a urine human chorionic gonadotropin level should be sent as her symptoms may be due to complications of pregnancy. Additional tests should be sent in select cases. Patients with diarrhea should have stool samples sent for culture and ova assessment. Importantly, Clostridium difficile culture and toxin measurements should be performed as the incidence of this infection is increasing within the community.9 Women in the third trimester of pregnancy with right upper quadrant pain, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets should be assessed for HELLP syndrome; expedient diagnosis is necessary to get the patient lifesaving plasma exchange therapy.10 DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING Diagnostic imaging should be the final step in the work up of a patient with an acute abdomen. It is imperative that, prior to ordering any diagnostic imaging, a working differential diagnosis has been formulated so that the appropriate modality is chosen. There is a wide range of options. Many are expensive and can expose patients to ionizing radiation, so it is important to choose the most useful modality for the patient being worked up. Ultrasound is a relatively cheap and expedient imaging modality that can be very useful in evaluating the acute abdomen. It remains the best modality for evaluating right upper quadrant pain, especially pain that is suspected to emanate from the gallbladder. Ultrasound sensitivity and specificity are high for detecting pericholecystic fluid, gallbladder wall thickening, and gallstones.11 It is also a useful modality for diagnosing appendicitis in patients where avoiding ionizing radiation is desired, such as the pediatric population and early pregnancy.12,13 When ruling out gynecologic sources of acute abdominal pain, transvaginal ultrasound should be utilized as it is more accurate than transabdominal ultrasound. Ultrasonography can have limitations with visualization due to abdominal wall thickness, bowel gas contents and operator experience. Plain films of the abdomen can provide useful information in certain patients. When concerned for hollow viscus perforation, an upright plain film taken at the level of the diaphragm will reveal free air under the diaphragm which is diagnostic and should prompt surgical exploration (Fig. 46.3). It has been shown that time to surgical consultation and time to the operating room is shorter if diagnosis can be made with plain film as opposed to CT. However, CT can provide more information regarding location of perforation and specific cause.14 Historically, upright and supine radiographs of the abdomen have been used to diagnosis bowel obstructions. Small bowel obstruction is suspected on plain film when air-fluid levels are seen in the upright position and paucity of gas in the distal colon with distended bowel loops in the supine position. Haustral markings from the teniae coli will help differentiate small bowel gas from colonic gas (Fig. 46.4). However, the diagnostic accuracy of plain films to diagnose mechanical bowel obstruction or paralytic ileus in a patient with abdominal pain is low.15 Colonic volvulus can be diagnosed on plain films as well. Cecal volvulus typically appears as a comma shape loop of bowel with the concavity facing inferiorly and to the right. Sigmoid volvulus presents as the “bent inner tube” or “coffee bean” sign, where the apex of the dilated colon points into the right upper quadrant (Fig. 46.5). FIG. 46.3 Upright plain abdominal film demonstrating pneumoperitoneum, a finding consistent with perforated hollow viscus. FIG. 46.4 An abdominal film of a patient with large bowel obstruction. The dilated loop of bowel can be identified as transverse colon by the haustral markings. CT has become the primary diagnostic tool in patients with abdominal pain over the past decades. It is readily available, provides detailed information about the entire abdomen and pelvis, and can be performed relatively quickly. The quality of the CT images is less dependent on operator skill than ultrasound and provides more detail than plain films. A differential diagnosis will guide the CT technique needed. For example, if nephrolithiasis is suspected the imaging will be done without contrast but if a small bowel obstruction is suspected the CT should be ordered with CHAPTER 46 Acute Abdomen 1141 Diagnostic Laparoscopy Diagnostic laparoscopy can be used as a final diagnostic adjunct should other tests prove equivocal; the advantage is that it may also prove therapeutic. A study of patients over 70 years old compared laparoscopic versus open exploration and intervention for the acute abdomen. The laparoscopic group showed no difference in morbidity or mortality.20 Laparoscopy can be safely used in patients with sepsis if measures to reduce the negative hemodynamic effects of pneumoperitoneum are employed; these include keeping the intraabdominal pressure under 12 mm Hg and making sure appropriate antibiotics have been given prior to insufflation. Diagnostic laparoscopy should not be used when irreversible sepsis is present or if the operator is uncomfortable with laparoscopy. An emergency situation is not the appropriate time to learn new skills. A relative contraindication to diagnostic laparoscopy is extremely dilated bowel as visualization can limit complete exploration, but this would depend on the surgeon’s comfort with laparoscopy.21 While it should not be used routinely, diagnostic laparoscopy can assist determining the cause of the acute abdomen in select cases. INTRAABDOMINAL PRESSURE MONITORING FIG. 46.5 Abdominal plain film showing sigmoid volvulus. Note the distended sigmoid colon in the right upper quadrant; this is the classic “coffee bean” or “bent inner tube” sign. oral and intravenous contrast. These considerations are essential to provide the most diagnostic images. Many studies have shown the improved diagnostic accuracy of CT over other imaging modalities. It has been shown that using CT as part of an imaging pathway will result in earlier diagnosis, though it will not decrease hospital stay or morbidity.16 This is particularly true for appendicitis (Fig. 46.6). A recent evidencebased review reported that the sensitivity and specificity of CT for identifying appendicitis were 98.5% and 98%, respectively. Several studies included in this review showed a decrease in the negative appendectomy rate with the use of CT.17 A retrospective study sought to determine the effect of CT imaging on diagnosis and disposition in patients over age 80. They found that their diagnosis changed in 43% of patients after obtaining a CT; this difficulty with diagnosis was particularly prominent in the presence of small bowel obstruction, colonic obstruction, and diverticulitis. Clinically, the findings on CT resulted in a statistically significant change in disposition.18 These findings demonstrate the usefulness of CT. Due to the radiation exposure associated with CT, studies have sought whether low-dose imaging retains diagnostic accuracy. In one recent study, two radiologists compared high-dose and lowdose CT images in patients with nontraumatic abdominal pain. They reported high confidence in their interpretation for both radiation doses despite there being slightly more image noise in the low-dose images. Diagnostic accuracy was not statistically significant between radiation doses; the low-dose CT had a sensitivity and specificity of 93.7% and 88.2%, respectively, while the highdose CT had a sensitivity and specificity of 95.8% and 94.1%, respectively.19 Low-dose CT should be considered in children and patients who undergo frequent imaging. The acute abdomen can either cause or be due to increased intraabdominal pressure. If the intraabdominal pressure is sustained above 20 mm Hg it is defined as abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). This is a life-threatening condition as the elevated pressure results in decreased venous return and tidal volumes from elevated inspiratory pressures. It can also lead to visceral ischemia due to poor perfusion. Normal intraabdominal pressure should be between 5 to 7 mm Hg. Abdominal obesity, accessory muscle respiration, and upright positioning will all artificially increase intraabdominal pressure. Bladder catheter pressure monitoring is used to measure intraabdominal pressures. The World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (WSACS) recommends measuring bladder pressures after instilling 25 mL of room temperature saline into the bladder. The patient should be supine with the transducer at zeroed at the midaxillary line. Pressure measurements should be taken at the end of expiration or with the patient paralyzed with the ventilator paused if unable to participate in exam.22 Grades of intraabdominal hypertension can be seen in Table 46.2. Treatment of intraabdominal hypertension and ACS depends on the cause and severity. Primary ACS is due to a disease process within the abdomen that is best treated with decompressive laparotomy and correction of the inciting disease process. Abdominal closure may not be possible without causing recurrent ACS which should prompt use of a temporary abdominal closure maneuvers. Secondary ACS is a condition that arises from a condition not located in the abdomen or pelvis. Initial management of secondary ACS without evidence of end organ damage should be treated medically. Medical management includes correcting a positive fluid balance, evacuating intraluminal contents via a nasogastric tube, Foley and enemas, relaxing the abdominal wall with adequate sedation and pain control, and drainage of peritoneal fluid.22 A low threshold should be held for decompressive laparotomy to limit morbidity and mortality from this condition. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Formulation of the differential diagnosis for an acute abdomen should be a continuous process throughout every step of evaluation. The list developed after history and physical examination 1142 SECTION X Abdomen A A B FIG. 46.6 (A) Computed tomography demonstrating a dilated retrocecal appendix (arrow) with periappendiceal stranding. (B) This image represents a pelvic abscess (A) caused by perforated appendicitis. The arrow shows the inflammatory process extending into subcutaneous tissues. TABLE 46.2 Abdominal hypertension and treatment by grade. INTRAABDOMINAL PRESSURE Normal pressure Grade 1 hypertension Grade 2 hypertension Grade 3 hypertension Grade 4 hypertension 5–7 mm Hg 12–15 mm Hg 16–20 mm Hg 21–25 mm Hg >25 mm Hg should guide the laboratory and imaging tests you order. By the end of the evaluation, the list of potential diagnoses should be narrowed to one or two processes. The art of refining differential diagnoses requires extensive knowledge of the medical and surgical causes of acute abdominal pain. This knowledge must then be integrated with the demographics of the patient being evaluated. It is imperative to determine early whether the disease process causing acute abdominal pain requires urgent surgical intervention. Many present with sepsis which must be managed expediently, even without a specific diagnosis. Box 46.5 presents examination, laboratory, and imaging findings associated with surgical disease. However, in real world situations, the patient may not be stable enough to be transported to another department for some of these tests. One option is to consider a test that can be performed at bedside such as ultrasonography or abdominal plain films. Another option is diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Using local anesthetic, a small incision is made in the midline near the umbilicus. A catheter is placed into the peritoneal cavity to infuse 1 L of normal saline, which is then siphoned out of the abdomen. The siphoned fluid is sent for cellular and biochemical analysis. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage can be used to detect hemoperitoneum and/or hollow viscous perforation. Delays in surgical intervention should be avoided. Once you have diagnosed a patient with a surgical abdomen, there is no advantage to waiting for further diagnostic tests. Morbidity and mortality increase with unwarranted delays. Fluid resuscitation and stabilization of vital signs can continue in the operating room through multidisciplinary approach with anesthesia and nursing. Laparoscopy can assist in guiding placement of the laparotomy incision if forced to proceed to the operating room without a definitive diagnosis. TREATMENT None Maintain euvolemia Nonsurgical decompression (diuresis, etc.) Surgical decompression via laparotomy Surgical decompression; explore for cause Findings that suggest need for surgical intervention. BOX 46.5 Physical Exam Findings Abdominal compartment pressure >25 mm Hg Involuntary guarding Rebound tenderness Pain out of proportion to exam Unexplained systemic sepsis Transabdominal penetrating trauma Laboratory Findings Anemia from gastrointestinal hemorrhage requiring >4 units of blood transfusion Evidence of hypoperfusion (acidosis, rising creatinine, rising liver function tests) Diagnostic Imaging Findings Pneumoperitoneum Progressive dilatation of stationary loop of intestine (sentinel loop) Evidence of bowel perforation (air or contrast near loop of bowel) Fat stranding or thickened bowel wall with systemic sepsis Bowel wall pneumatosis Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage Findings Presence of feculent or particulate matter >250 white blood cells per milliliter >300,000 red blood cells per milliliter Peritoneal bilirubin > serum bilirubin (bile leak) Peritoneal creatinine > serum creatinine (urine leak) CHAPTER 46 Acute Abdomen Some patients are diagnosed with a medical cause of acute abdominal pain. This does not mean that a surgical process will not develop. These patients need close, careful observation in a monitored setting. Serial examinations and laboratories should be scheduled to ensure the patient is improving with medical therapy. Ideally, examinations are performed by the same examiner to avoid missing significant changes in the patient’s condition or development of complications. PREPARATION FOR EMERGENCY OPERATION Patients with an acute abdomen vary greatly in their overall state of health at the time the decision to operate is made. Regardless of the patient’s severity of illness, all patients require some degree of preoperative preparation. Intravenous access should be obtained, and any fluid or electrolyte abnormalities corrected. Nearly all patients will require antibiotic infusions. The bacteria common in acute abdominal emergencies are gram-negative enteric organisms and anaerobes. Infusions of antibiotics to cover these organisms should be begun once a presumptive diagnosis is made. Patients with generalized paralytic ileus or vomiting benefit from nasogastric tube placement to decrease the likelihood of vomiting and aspiration. Foley catheter bladder drainage to assess urine output, a measure of adequacy of fluid resuscitation, is indicated in most patients. Acidosis due to intestinal ischemia or infarction may be refractory to preoperative therapy. Significant anemia is uncommon, and preoperative blood transfusions are usually unnecessary, however cross-matched blood should be available at operation. The need for preoperative stabilization of patients must be weighed against the increased morbidity and mortality associated with a delay in the treatment. The underlying nature of the disease process, such as infarcted bowel, may require surgical correction before stabilization of the patient’s vital signs and restoration of acid-base balance can occur. Resuscitation should be viewed as an ongoing process and continued after the surgery is completed. Deciding when the maximum benefit of preoperative therapy in these patients has been achieved requires good surgical judgment. SPECIAL PATIENT POPULATIONS Pregnancy The workup and treatment of acute abdominal pain in the pregnant patient creates several unique diagnostic challenges. Providers often rely on imaging to differentiate between an urgent surgical problem from a nonsurgical or obstetric cause.23 However, the greatest threat facing the pregnant patient with acute abdominal pain is the potential for delayed diagnosis and which have been proven to be far more morbid than the operations themselves.24,25 Delays occur for several reasons: symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting are often attributed to the underlying pregnancy, pregnancy can alter the presentation of some disease processes and make the physical examination more challenging because of the enlarging uterus, and fear of exposure of a fetus to radiation or unnecessary procedures.26 Laboratory studies such as white blood cell counts and other chemistries are also altered in pregnancy, making recognition of disease processes more difficult. These differences cause extra emphasis to be placed on other modalities, such as vital signs and laboratory studies, which can confuse or underestimate the extent of intraabdominal disease. Finally, physicians naturally tend to be more conservative in treating pregnant patients, especially in regard to imaging and surgical intervention. 1143 Ultrasound is the initial imaging study of choice in the pregnant patient.26,27 In addition to diagnosing the most common abdominal pathologies, appendicitis and cholelithiasis, this modality also adds the benefit of assessment of the fetus and evaluating for obstetrical pathology.27 Radiation exposure should be avoided whenever possible, especially during the first trimester during organogenesis, and the next study of choice should be MRI.26,27 If CT is the only imaging study available, risks and benefits should be weighed as a delay in diagnosis is often more morbid than a single imaging study. Studies have shown that up to 50 mGy of ionizing radiation, the equivalent of five abdominal plains films or one abdominal CT scan, results in no significant increase in teratogenic effects of radiation.27 Whenever possible, such as during imaging of the brain, cervical spine, or chest x-ray, the fetus should be shielded with lead. It is important to remember that pregnancy is a highly controlled process that involves almost every organ system in a selfregulated environment that is extremely sensitive to maternal volume loss and catecholamine response.26 Maternal hemorrhage is often compensated by decreased uterine flow, and marked fetal distress is often the first manifestation of an acute surgical pathology, even before maternal hypotension or tachycardia is identified.26 The presence of peritoneal signs is not a normal finding in pregnancy, and the development of peritonitis can often be delayed by abdominal laxity and an enlarged uterus. Its presence should prompt an immediate search for its cause to avoid additional morbidity and mortality.28 The differential diagnosis of acute abdomen in pregnancy can be broad; however, the presentation does not differ much from that of the adult patient if one pays special attention to patient symptomatology and history. The most common pathologies and the recommended screening imaging studies are listed in Table 46.3. In addition to gastrointestinal pathology, it is important to include gynecologic and obstetrical causes of acute abdomen in the patient’s workup, including uterine rupture, ectopic pregnancy, ruptured corpus luteum cyst, adnexal torsion, placenta percreta, among others.27 Ovarian torsion can often be distinguished from other abdominal pathology with its characteristic presentation of waxing and waning abdominal pain.28 Acute appendicitis is the most common nonobstetric abdominal emergency requiring surgery with an overall incidence of 101 cases per 100,000 pregnancies.23 Diagnostic findings on ultrasound are a dilated, blind-ending, thickened, tubular, and noncompressible structure 6 mm or larger in size.29 Ultrasound can have its limitations and should be followed by advanced imaging if the diagnosis is in question. MRI and CT findings are similar to ultrasound and also include periappendiceal inflammation, presence of an appendicolith, or the presence of an established abscess.29 Twenty percent of patients will have peritonitis or established intraabdominal abscess at presentation, with an associated higher risk of complications including a 20% to 35% rate of fetal loss for perforated appendicitis.23 The added difficulties in evaluating the pregnant patient with right lower quadrant abdominal pain have resulted in significantly higher negative appendectomy rate compared with nonpregnant patients in the past. Although this diagnostic error rate would be unacceptable in a typically young healthy woman, it is widely accepted because of the fetal mortality risk when appendicitis progresses to perforation before surgery. General anesthesia is considered safe in all stages of pregnancy and patients should be considered a high aspiration risk for induction. Pregnant women should be treated as though they have 1144 SECTION X Abdomen TABLE 46.3 Differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in pregnancy and recommended imaging studies. SITE PREFERRED IMAGING MODALITY FOR DIAGNOSIS Gallbladder disease Hepatitis Pancreatitis Bowel obstruction Perforated ulcer Appendicitis Nephrolithiasis Inflammatory bowel disease Gynecologic causes Diverticulitis Trauma US > MRI US > MRI US > MRI > CT US > MRI > CT Plain films > CT US > MRI > CT US > MRI > CT MRI > CT US > MRI MRI > CT US > CT> MRI Adapted from Baheti AD, Nicola R, Bennett GL, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of abdominal and pelvic pain in the pregnant patient. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2016;24:403–417. CT, Computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasound. a full stomach whenever intubation is planned.28 Intraoperative care during pregnancy is focused on optimal care of the mother. If the fetus is previable, fetal heart tones should be measured before and after the surgery. If the fetus is viable, fetal heart tones should be measured throughout the surgery with a provider capable of performing an intervention available. The safety of laparoscopic surgery in pregnancy has been extensively studied and established. Laparoscopy allows for decreased manipulation of the uterus, and as a result, less uterine irritability with lower risk of contractions, spontaneous abortions, preterm labor, and premature delivery.30 In order to safely enter the abdomen, the open Hassen technique is considered standard, with care to avoid injury to the enlarging uterus.31 Additional causes of acute abdomen include biliary disease, bowel obstruction, and pancreatitis, among others. Biliary disease is common, as sex steroids interfere with gallbladder emptying resulting in bile stasis.28 Ultrasound is the diagnostic test of choice. Treatment is recommended in the second trimester to avoid complications of biliary disease as the pregnancy progresses. Gallstone pancreatitis and acute cholecystitis should be managed more carefully. Gallstone pancreatitis has been associated with a fetal loss as high as 60%. If a woman does not respond quickly to conservative treatment with hydration, bowel rest, analgesia, and judicious use of antibiotics, further evaluation should be performed as surgical intervention may be indicated. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is considered safe and low radiation risk to the fetus, should the patient present with cholangitis or choledocholithiasis. Small bowel obstruction is often confused with the normal nausea and vomiting associated with pregnancy. It is important to remember that peritoneal signs in the presence of nausea and vomiting is never considered normal and should prompt further workup.28 Abdominal distention with colic should key the clinician to the diagnosis. Pediatrics Evaluating a child with an acute abdomen can be difficult for the clinician not accustomed to performing an abdominal exam in children. In contrast to performing an examination on an adult who is able to communicate with the clinician and give feedback when abdominal pain is elicited, much of the examination on a child occurs through observation. Children can be poor historians because of their age, being afraid of the situation, and being unable to verbalize their symptoms. Clues to the extent of peritoneal irritation include a child’s willingness or unwillingness to stand or move about the hospital bed freely. Children with peritonitis will demonstrate abdominal pain with standing, jumping, or coughing.3 The abdominal exam should be performed thoughtfully and only to the extent to identify the presence of abdominal wall spasm in response to intraabdominal pathology. The most common cause of acute surgical abdomen in the pediatric population remains acute appendicitis and occurs most commonly in older children and adolescents with a presentation of anorexia, low-grade fever, and right-lower quadrant pain similar to adult patients.32 Younger children may present differently and pose a challenge to the clinician with reports from parents of a vague onset of symptoms. Their inability to characterize their pain, nonspecific signs, and difficulty in eliciting a physical exam results in imaging playing a crucial role in diagnosis. Almost all children, 99% in some reports, with appendicitis will have preoperative imaging before surgical intervention.32–34 Ultrasound often demonstrates pathologic concordance when performed in the hands of an experience ultrasonographer, especially those performed at a free-standing children’s hospital.34 Children presenting to a nonchildren’s hospital are more likely to have a CT scan diagnosis of appendicitis, despite the recommendations from multiple pediatric societies on the risks of radiation.34 Additional causes of acute abdomen are broken down by age and listed in Table 46.4. Intussusception should be considered in the differential of abdominal pain in children less than 3 years old. Gastroenteritis, Meckel diverticulitis, and C. difficile colitis are among other causes of abdominal pain, and presentation is similar to adult patients. Inconsolable crying and lethargy in small infants can be ominous. Any history of emesis in a newborn should prompt careful questioning regarding the character and timing of emesis episodes; bilious emesis is a surgical emergency and prompts urgent evaluation for midgut volvulus. A history of fever, passage of currant jelly stools, and lower gastrointestinal track bleeding should prompt further workup.35 Critical Illness Establishing a diagnosis of an acute abdomen in the critically ill can be challenging. The clinician must navigate an environment of deep-sedation, multiple etiologies of sepsis, multiorgan failure, CHAPTER 46 Acute Abdomen 1145 TABLE 46.4 Differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in children by age. < 2-YEARS OLD 2- TO 5-YEARS OLD 5- TO 12-YEARS OLD >12-YEARS OLD Intussusception Gastroenteritis Constipation Infantile colic Malrotation with midgut volvulus Incarcerated inguinal hernia Obstruction due to Hirschsprung disease UTI Meckel diverticulum Intussusception Appendicitis Gastroenteritis Constipation Mesenteric adenitis Malrotation with midgut volvulus Sickle cell crisis Appendicitis Gastroenteritis Constipation Mesenteric adenitis Functional abdominal pain Pneumonia Sickle cell crisis Appendicitis Gastroenteritis Constipation Ovarian/testicular torsion Dysmenorrhea Pelvic inflammatory disease Ectopic pregnancy Henoch-Schonlein purpura UTI Trauma Meckel diverticulum Henoch-Schonlein purpura UTI Trauma Adapted from Yang WC, Chen CY, Wu HP. Etiology of non-traumatic acute abdomen in pediatric emergency departments. World J Clin Cases. 2013;1:276–284. UTI, Urinary tract infection. TABLE 46.5 Differential diagnosis of acute abdomen in transplant patients. LIVER37 LUNG38 HEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELL39 Biliary complications of transplant Vascular complications of transplant Small bowel obstruction Acute appendicitis Urinary tract infection Acute diverticulitis Acute pancreatitis Gastroesophageal reflux Infectious enterocolitis Peptic ulcer disease Gastroparesis Diverticulitis Pancreatitis Gastrointestinal bleed Acute graft versus host disease Cholangitis Neutropenic enterocolitis Infectious enterocolitis Pneumatosis and absent or subtle clinical exam findings. Unrecognized abdominal pathology can cause patients to persist in their critical state or even progress to their demise. Critically ill patients may not be able to demonstrate the typical signs and symptoms of acute abdomen due to narcotic analgesia, blunting of the inflammatory response due to antibiotics or immunosuppression, and nutritional deficiency. Imaging is often necessary to establish a diagnosis as multiple causes for abdominal distention, sepsis, or organ failure may be at play in the intensive care unit (ICU) patient.36 Some patients, will be unstable for transport and the clinician will be challenged with the risks and benefits of obtaining advancing imaging, such as CT, versus operative exploration with the potential of a nontherapeutic laparotomy. Determining which patients are stable enough to survive an operation, potentially a nontherapeutic intervention, can be unpredictable.37 A small cohort of clinicians advocate for diagnostic laparoscopy in the ICU as a mode of both diagnosis and treatment of the acute abdomen in the critically ill patient. However, this is coupled with the difficulties of performing bedside laparoscopic surgery, the invasive nature of procedure, and the costs of the equipment and anesthesia.37 As technology continues to advance, this is an area where change is likely to occur. Immunocompromised Transplant patients often present to the emergency room with abdominal complaints. In one study, researchers found that 33% to 60% of transplant patients sought care in the emergency room after their procedure.38 Inflammation is necessary in the pathophysiology of abdominal pain and peritonitis, and this may be blunted in the transplant patient. This can result in unreliable leukocytosis, delayed development of fever, and subjectively decreased abdominal symptoms. They may also present in a delayed fashion, which may be very quickly followed by overwhelming systemic collapse. As a result, although the abdominal pathology is similar to that seen in healthy adult patients, the immunosuppressed may have atypical presentations with very minimal symptoms. In one study of over 70,000 transplant patients, the incidence of emergency surgery was found to be 2.5%. The indications for surgical intervention were biliary disease (80%), gastrointestinal perforation (9%), complicated diverticulitis (6%), small bowel obstruction (2%), and appendicitis (2%). Overall mortality in this patient cohort was 5.5%.38 A differential diagnosis of abdominal pathology is listed in Table 46.5 broken down by type of transplant. Routine blood work should be performed in addition to checking serum levels of immunosuppressive drugs. These medications can cause many side effects that may cloud the presentation of acute abdomen, including loss of gastrointestinal mucosal integrity and regeneration, alterations in gastric acidity, and impaired immune response to illness. This often presents as diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss.38 Transplant patients may not mount an inflammatory response to illness, and serum markers may not be elevated despite ongoing abdominal pathology. Pseudomembranous colitis has increasingly been seen in the immunocompromised patient, independent of a recent association with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Typical presentations 1146 SECTION X Abdomen include diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, and leukocytosis; however, this may not be seen in this patient cohort. A high index of suspicion, reliance on CT imaging and stool assays should be considered early. Cytomegalovirus infection is another important pathogen to consider in the transplant patient. The presentation can vary, including diarrhea, dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, and intestinal perforation. Cytomegalovirus is diagnosed by biopsy demonstrating virus in the gastric or intestinal mucosa and is treated with antivirals. Atypical infections, including peritoneal tuberculosis, fungal infections, and endemic mycoses, can also be seen in this group. Due to the decreased inflammatory response, an abdominal infection may not present with a typically walled off abscess and CT scan imaging may not demonstrate classic findings.39 Immunosuppressed patients with suspicious abdominal pathology should have inpatient monitoring with a low threshold for operative intervention if an atypical infection that is not improving despite adequate therapy. Cardiac Patients Risk factors for the development of gastrointestinal complications after cardiothoracic surgery. BOX 46.6 • Age >70 • Low cardiac output • Peripheral vascular disease • Need for reoperation due to hemorrhage • Acute/chronic renal failure • Cardiopulmonary bypass time >150 minutes • Intraaortic balloon pump • Preoperative inotropic support • Active smoker • Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease • Prolonged ventilation • Valve surgery • Sepsis/sternal wound infections • Liver failure • Myocardial infarction Abdominal emergencies in the cardiac patient can be easily masked by their postoperative recovery, ongoing management of their cardiac dysfunction, mechanical ventilation, arrhythmias, hemodynamic instability, and sedation.40 Risk factors are associated with the procedure performed, such as length of cardiopulmonary bypass, interventions on valvular heart disease, and need for intraaortic balloon pump. In addition, the patient’s preoperative physiology also has some effect, such as arrhythmias, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, renal disease, and need for preoperative inotropic support.41 Patients undergoing an open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair have the highest incidence, especially those repaired through a transabdominal approach. The highest mortality is seen in patients with intestinal ischemia and in those patients who required a valve repair.40 The pathophysiology of gastrointestinal complications is thought to be associated with disturbances in the superior mesenteric artery blood flow during cardiopulmonary bypass.42 The most common gastrointestinal diagnoses are ileus, pancreatitis, mesenteric ischemia, bowel obstruction, acute cholecystitis, and perforation.41 Risk factors for development of an abdominal complication after cardiothoracic surgery are listed in Box 46.6. From Buczacki SJA, Davies J. The acute abdomen in cardiac intensive care unit. In: Valchanov K, Jones N, Hogue CW, eds. Core topics in cardiothoracic critical care. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018:294–300. Morbidly Obese may require multiple films to image the entire abdomen. CT may be limited due to weight restrictions on the examination table, although this is increasingly becoming less of an issue due to the increasing numbers of morbidly obese patients. Early laparoscopy, especially in the postoperative bariatric patient, is often used for both diagnosis and treatment. Examples of concerning CT imaging findings are listed in Box 46.7. The classic presentation of an acute abdomen is not a reliable indicator of intraabdominal pathology in the morbidly obese. The presentation is often subtle, leading to rapid progression to sepsis, organ failure, and death.42 In contrast to normal weight patients, the morbidly obese can mask the signs of peritonitis, even in the setting of abdominal catastrophes, such as anastomotic leaks, until very late in the disease process, leading to a high incidence of complications and increased mortality.42 Physical examination findings are difficult to interpret. Abdominal sepsis may only be associated with malaise, shoulder pain, hiccups, and shortness of breath.43 Severe abdominal pain is uncommon. Appreciation of abdominal distention or a mass is difficult because of their increased abdominal girth. The presence of anorexia is also highly unpredictable, and their reported symptoms or abdominal complaints can be exceedingly vague. With an unreliable physical exam, clinicians must rely on laboratory exams, tachycardia, x-ray imaging findings, and subtle clinical symptoms to make the diagnosis of an abdominal problem.42 Abdominal x-rays have reduced clarity and Concerning CT imaging findings in the postbariatric surgery patient. BOX 46.7 • Dilated alimentary limb • Dilated excluded stomach • Dilated biliopancreatic limb • Transition between dilated and nondilated bowel • Mesenteric swirl sign • Cluster of small bowel loops • Horizontal position of the superior mesenteric artery From Karila-Cohen P, Cuccioli F, Tammaro P, et al. Contribution of computed tomographic imaging to the management of acute abdominal pain after gastric bypass: correlation between radiological and surgical findings. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1961–1972. CT, Computed tomography. Elderly The diagnosis of an acute abdomen in the elderly patient is no different from that of the adult patient. This patient population, however, is unique in that they often suffer from delay in surgical treatment as a result of their age due to biases regarding the morbidity of the proposed intervention. This often occurs despite data to suggest that increased age does not independently affect mortality, morbidity, or length of hospital stay.44 With an aging population, surgeons and clinicians are now challenged with how to care for this patient cohort, and they must let go of their strong-held beliefs that patients can be “too old,” “too high risk,” CHAPTER 46 Acute Abdomen BOX 46.8 Differential diagnosis of acute abdomen in the elderly patient. BOX 46.9 • Peptic ulcer disease • Gastrointestinal bleed • Biliary disease • Pancreatitis • Bowel obstruction (large and small) • Volvulus • Diverticulitis • Appendicitis • Abdominal aortic aneurysm • Mesenteric ischemia • Tumor infiltration • Gastrointestinal bleed • Bowel obstruction • Biliary disease • Appendicitis • Neutropenic enterocolitis • Invasive aspergillosis • Digestive tract graft versus host disease • Mesenteric ischemia • Diverticulitis From Rubinfeld I, Thomas C, Berry S, et al. Octogenarian abdominal surgical emergencies: not so grim a problem with the acute care surgery model? J Trauma. 2009;67:983–989; and Magidson PD, Martinez JP. Abdominal pain in the geriatric patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2016;34:559–574. or “nonsurvivable.”45 Approaching these patients with a “damagecontrol” mentality of aggressive resuscitation and careful attention to hypothermia, coagulopathy, acidosis, or hypotension and returning after adequate resuscitation are suggested to improve outcomes.45 Box 46.8 lists the most common indications for surgical intervention in the elderly patient population. Advanced Disease Surgery in patients with advanced or disseminated cancer can be fraught with complications with little chance of prolonging their survival. Emergency procedures, such as for perforation or obstruction, are performed in this patient population with grave risks, as their disseminated disease has little chance of cure. One study demonstrated that those that undergo an operation for perforation have an approximate 1 in 3 chance of mortality; this is only slightly improved to 1 in 6 for those undergoing an operation for obstruction.46 These complications may occur as a side effect of cancer treatment or it may represent disease progression. Regardless the cause, frank discussion with patients and their families are fundamental, and decisions regarding the patient’s goals of care, overall survival, and prolonged institutionalization should be discussed with respect to the patient’s wishes.46 Emergency surgery in patients with advanced disease often heralds an inflection point in their care and these patients are unlikely to obtain their goal of discharge home.46 Box 46.9 lists the differential diagnosis of acute abdomen in the oncologic patient. SUMMARY Despite improvements in laboratory examinations and imaging, the evaluation and management of the patient with acute abdominal pain remains a challenging part of a surgeon’s practice. However, a careful history and thorough physical examination continue to remain the most important part of the evaluation of the patient with acute abdominal pain. The surgeon continues to be required to make the decision to perform laparoscopy or laparotomy with some degree of uncertainty as to the expected findings. The increased morbidity and mortality associated with a delay in the treatment of many of the surgical causes of the acute abdomen argue for an aggressive and expeditious surgical approach. 1147 Differential diagnosis of acute abdomen in the oncology patient. From Mokart D, Penalver M, Chow-Chine L, et al. Surgical treatment of acute abdominal complications in hematology patients: outcomes and prognostic factors. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:2395–2402; and Cauley CE, Panizales MT, Reznor G, et al. Outcomes after emergency abdominal surgery in patients with advanced cancer: Opportunities to reduce complications and improve palliative care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:399–406. SELECTED REFERENCES Bouyou J, Gaujoux S, Marcellin L, et al. Abdominal emergencies during pregnancy. J Visc Surg. 2015;152:S105–115. This paper reviews the presentations of abdominal emergencies in pregnant patients as well as the best way to approach these conditions. de Burlet KJ, Ing AJ, Larsen PD, et al. Systematic review of diagnostic pathways for patients presenting with acute abdominal pain. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30:678–683. An excellent resource for systematic evaluation and diagnosis in a patient with an acute abdomen. Malbrain ML, Cheatham ML, Kirkpatrick A, et al. Results from the international conference of experts on intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. I. Definitions. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1722–1732. A consensus statement that defines abdominal compartment syndrome and provides evidence-based algorithm on its diagnosis and treatment. Navez B, Navez J. Laparoscopy in the acute abdomen. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:3–17. This paper highlights the usefulness of minimally invasive surgery in approaching the acute abdomen. Steinheber FU. Medical conditions mimicking the acute surgical abdomen. Med Clin North Am. 1973;57:1559–1567. This classic article nicely reviews the various medical conditions that can manifest as an acute abdomen. It is well written and remains pertinent to the evaluation of these patients.