Financial Accounting & Reporting: A Global Perspective Textbook

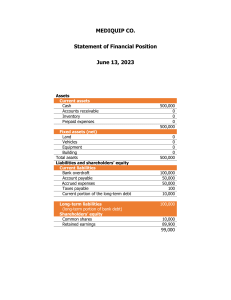

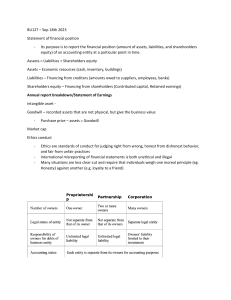

advertisement