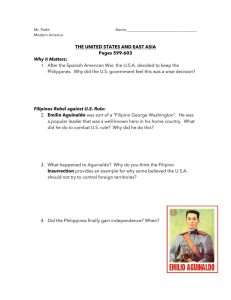

UNIT III PHILIPPINE WRITING DURING THE PERIOD OF EMERGING NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS THE PHILIPPINES IN THE 19TH CENTURY Major forces were at work in the 19th century which were to eventually lead to the cretion of national conciousness among the Filipino people and culminate in the separation of the colony from spain. With the opening of its ports to international trade in 1834 and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the Philippines was plunged into an era of significant socio-economic changes. The foreign markets' interest in the archipelago's export products such as abaca, copra, sugar, and tobacco opened up vast tracts of land for cultivation. Attracted by the islands' economic potentials, foreign firms moved in to engage in commercial agriculture, stepping up production through improved machines and scientific methods of cultivation. Banking and other credit facilities were opened. The increase in international trade brought in more revenues and on the whole, improved the colony's economic conditions. Relative prosperity was especially enjoyed by a small group of indios and mestizos engaged in agriculture and trade. This group became the nucleus of an emerging middle class. With their wealth, they inevitably acquired social prestige and rose to positions of prominence in their communities. They sent their children to good schools in Europe as well as in Manila. By then university education in the country had been opened to the natives following the pas- sage of the Educational Degree of 1863. Those who went abroad stepped right into the liberal atmosphere of the European continent. The experience awekened them to the urgent need for governmental reforms in the colony. The opening of the Philippines to world trade also allowed a steady flow into the country of liberal ideas and of information regarding political and economic developments abroad. Emboldened by developments in Europe and by the appoinment in 1869 of a sympathetic and liberal governor-general, Carlos Ma. de la Torre,, the middle class spearheaded a movement for reforms. Hitting at the abuses and discriminating practices of the Spanish civil and religious authorities they agitated for equal political rights with the Spanish nationals. At the same time, the Filipino clergy was carrying on its movement for the secularization of the parishes. Leading the movement was Fr. Pedro Pelaez who wrote letters and articles defending the native priests' ability to administer parishes and their loyalty to Spain. After his death, his young disciple, Fr. Jose Burgos, continued the stuggle by writing articles and pamphlets in be- half of the native clergy. The movement for reforms grew until stringent measures were taken to suppress it by Dela Torre's successor, Rafael de Izquierdo. The execution of the three priests, Frs. Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora at Bagumbayan in 1872 and the widespread imprisonment, exile and execution of other patriots put a temporary halt to the movement locally. But it also forced a number of Filipinos to escape to European, particularly to Spain, to continue the work along with other idealistic natives pursuing their studies there. The last few decades of the century were thus a period of growing social conscious- ness and restlessness, marked specially by the appearance of two major movements: The Propaganda movement and, when it failed, the Revolutionary Movement. THE PROPAGANDA MOVEMENT AND THE LITERATURE OF PROTEST The organized movement which was to be labeled the "Propaganda Movement" was launched in Spain by a group of young college students and graduates, among whom were Jose Rizal, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Graciano Lopez- Jaena Mariano Ponce, Juan Luna, Felix Resurrection Hidalgo, Jose Ma. Panganiban, and Fernando Canon. The Propagandists were not out to work for the independence of the colony, but for its assimilation to Spain as a province and, consequently, for the treatment of the Filipinos as Spanish citizens, enjoying the same rights as the Spanish nationals. The writings of this period cannot be could literature, strictly speaking, except perhaps for the novels and poems of Rizal. Nevertheless, they are important to consider because of their role in developing a sense of nation- hood among the Filipinos. Published as occasional articles in various Madrid publications and in the propagandists, own newspaper. La solidaridad, they were mostly essays and tracts protesting against the denial of certain political rights to the Filipino people, belying the claims of some Spanish writers that the natives were recially and culturally inferior to the Spaniards and that the Philippines had no boast of before it became a Spanish colony. The most prolific writer among the propagandists was Rizal. Playwright, essayist, poet, and novelist, he wrote two plays, Junto al Pasig and El consejo de los dioses: an annotated edition of Morga's Sucesos de las islad filipinas; a number of essys, among which are "sobre la indolencia de los Filipinos" and "Filipino dentro de cien anos" around forty poems; and two novels, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo. His "Ultimo Adios" is con- sidered by critics as his poetical masterpiece. A much longer poem, however is "Mi Retiro," which we have included in this unit. Written in response to his mother's request, it is regarded as Rizal's profoundest noblest poem. Marcelo H. del Pilar, who used "Dolores Manapat" and "Plaridel" as pen names, was the Spanish authorities in the Philipines. His works were many and varied, among which were La Soberania monacal en filipinas and La frailocracia filipina, both of which exposed the abuses of the friars and their oppression of the indios; Caiigat Cayo, an indictmnet of Fr. Jose Rodriguez's critique of Rizal's Noli: and Dasalan at Toksohan, an antifriar satire written in parody of the cathechism and prayer book. His "Sagot ng Espanya sa Hibik ng Pilipinas" is a second of a triad of poems, the first having been written by Hermenegildo Flores, Del Pilar's teacher, and entitled "Hibik ng Pilipinas sa Ynang Espanya." Del Pilar's poem caused Andres Bonitacio to write a responce, completing the triad - "Katapusang Hibik nang Pilipinas. Graciano Lopez-Jaena founded La Solidaridad and was its editor until Del Pilar took over the editorships. Jaena wrote a novelette in Hiligaynon, Fray Botod, a satire about a potbellied, abusive, and immoral frair. To escape persecution by the friars whom he angered with his work, he fled to Spain THE REVOLUTIONARY PERIOD AND ITS WRITERS The Revolutionary Period had two phases. The first phase, the revolution against Spain, produced writings mostly in Tagalog and the literary field was dominated by the key men of the Katipunan, Andres Bonifacio and Emilio Jacinto. Bonifacio has two outstanding poems in Tagalog aside from his "Katapusang Hibik": "Pag-ibig sa Tinubuang Bayan" and "Pahimakas," a translation of Rizal's farewell poem. He also wrote Ang Dapat Mabatid nang mga Tagalog and Katungkulang Gagawin ng Mga Anak ng Bayan. An ardent revolutionary, Jacinto edited and contributed many articles to Kalayaan, the organ of the Katipunan. He wrote a series of articles on human rights, liberty, government, and love of country under the title "Liwanag at Dilim." Proficient in both Tagalog and Spanish, he is also known for "A la patria," written in the style of Rizal's "Ultimo Adios", "A mi madre”, a touching ode, and Kartilla ng Katipunan. The second phase of the Revolution was the Philippine-American War. It was marked by the appearance of serious essays and political discourses, mostly written by Apolinario Mabini, the "Brains of the Revolution." Mabini's most important literary work is El Verdadero Decalogo. REPRESENTATIVE WORKS MI RETIRO (A mi madre) - Jose Rizal Addition: Mi Retiro (“My Retreat”) was written by Rizal while in exile in Dapitan. From his mother’s prodding, Rizal revived his writing of poems where he expressed his serene life and his acceptance of his destiny and whatever justice will be given him. FRIAR BOTOD – by Garciano Lopes Jaena translated by Phyllis Tiongco Addition: The story of Fray Botod by Graciano Lopez Jaena portrayed an early Spanish priest from the colonial era of the Philippines as greedy, corrupt, hypocrite, gluttonous, and lustful. As a form of propaganda and protestation, his work aimed to expose these horrendous characteristics of these abusive priests. MY RETREAT – Traslated by Charles Derbyrshire Addition: (also known as “Mi Retiro” in Spanish) is a poignant poem written by Jose Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines. In this piece, Rizal reflects on his life during exile in Dapitan from 1892 to 1896. In “My Retreat,” Rizal celebrates the beauty of nature, the simplicity of existence, and the profound connection between humanity and the elements. His exile becomes a canvas for poetic reflection, reminding us that even in solitude, life can be abundant and meaningful. DASALAN AT TOCSOHAN (Excerpts) – Marcelo H. del Pilar Addition: The work criticizes the abuses committed by the friars against Filipinos during that time. It takes the form of a prayer booklet or pamphlet and features several parodies of prayers related to the friars’ greed, misconduct, and malpractices. In this biting satire, the friars are portrayed as replacing God, imposing their rules on the Filipino population. The work sheds light on the oppressive practices of the religious authorities and serves as a powerful commentary on the social and political climate of the period Amain Namin - a parody of the “Our Father” prayer. It humorously reimagines the traditional prayer, criticizing the friars and their hypocrisy. In this version, Marcelo Del Pilar uses biting language to expose their abuses of power. Aba Guinoong Baria - a satirical parody of the Catholic prayer “Hail Mary” (also known as “Ave Maria”). In this humorous version, the traditional phrases are replaced with irreverent lines that criticize the friars and their corrupt practices. HIBIK NG PILIPINAS SA YNANG ESPANA – by G.Herminigildo Flores Addition: “Hibik ng Pilipinas sa Inang Espanya” is a poignant Filipino poem written by Hermenegildo Flores in 1888. It expresses the Philippines’ lamentations and grievances toward Spain, its colonial motherland. The poem reflects the struggles and abuses faced by Filipinos during the Spanish colonial period. The poem highlights the exploitation by the clergy, excessive taxation, and the hardships endured by the Filipino people. Despite the suffering, the poem also emphasizes the Filipinos’ unwavering love for their homeland. The poem serves as a powerful critique of the oppressive Spanish rule and resonates with the sentiments of many Filipinos during that era. It stands as a testament to the resilience and longing for justice among the Filipino people. SAGOT NG ESPANA SA HIBIK NANG PILIPINAS – by Marcelo H. del Pilar Addition: The answer to the Spanish Cry of the Philippines is a famous poem by Marcelo H. del Pilar. It was written in response to Hermenegildo Flores' famous poem, "Cry of the Philippines to Mother Spain" in 1888. In the famous poem of Flores, the suffering of the Philippines under the Spanish is described. Del Pilar, on the other hand, responded to this popularity, in which he expressed the Philippines' grievances to Spain. Del Pilar's poem shows love for the country and opposition to the abuses committed by the invaders. It is an important part of Philippine literature that shows feelings of patriotism and resistance to colonialism. KATAPUSANG HIBIK NG PILIPINAS – by Andres Bonifacio Addition: (poem) It is a sign of hatred and threats to those who have taken over our country. In the poem, the Tagalogs express their deep feelings at the hands of their conqueror. PAG-IBIG SA TINUBOANG BAYAN – by Andres Bonifacio Addition: A compelling poem about one’s love for the nation -an ideology at the very heart of the revolution. FROM LIWANAG AT DILIM (Excerpts) – by Emilio Jacinto Addition: Liwanag at Dilim” (translated as “Light and Darkness”) is a thought-provoking essay written by Emilio Jacinto, a prominent figure in Philippine history. In this work, Jacinto delves into profound themes related to freedom, political authority, and the responsibilities of leaders. Kalayaan - The publication of the first issue of the Kalayaan helped swell the ranks of the Katipunan and win more adherents to its side. Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Jacinto, and Dr. Pio Valenzuela created Kalayaan, an all-Tagalog newspaper, to advocate for complete Philippine independence.