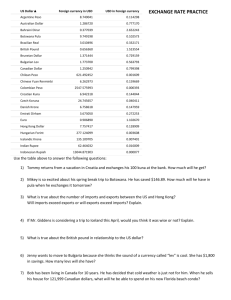

The International Monetary System What is the International Monetary System? • The institutional framework within which ▫ International payments are made ▫ Movements of capital are accommodated ▫ Exchange rates among currencies are determined Evolution of the International Monetary System • Bimetallism: Before 1875 • Classical Gold Standard: 1875-1914 • Interwar Period: 1915-1944 • Bretton Woods System: 1945-1972 • The Flexible Exchange Rate Regime: 1973Present Bimetallism: Before 1875 • Bimetallism was a “double standard” in the sense that both gold and silver were used as money. • Some countries were on the gold standard, some on the silver standard, and some on both. • Both gold and silver were used as an international means of payment, and the exchange rates among currencies were determined by either their gold or silver contents. Classical Gold Standard: 1875-1914 • During this period in most major countries: ▫ Gold alone was assured of unrestricted coinage. ▫ There was two-way convertibility between gold and national currencies at a stable ratio. ▫ Gold could be freely exported or imported. • In order to support convertibility into gold, banknotes needed to be backed by a gold reserve of a minimum stated ratio • The exchange rate between two country’s currencies would be determined by their relative gold contents. Classical Gold Standard: 1875-1914 • For example, if the dollar is pegged to gold at U.S. $30 = 1 ounce of gold, and the British pound is pegged to gold at £6 = 1 ounce of gold, it must be the case that the exchange rate is determined by the relative gold contents: $30 = 1 ounce of gold = £6 $30 = £6 $5 = £1 • Highly stable exchange rates under the classical gold standard provided an environment that was beneficial to international trade and investment Collapse of the Gold Standard • World War I ended the classical gold standard in August 1914 • Great Britain, France, Germany and Russia suspended redemption of banknotes in gold and imposed embargoes on gold exports Interwar Period: 1915-1944 • Exchange rates fluctuated as countries widely used “predatory” depreciations of their currencies as a means of gaining advantage in the world export market. • Attempts were made to restore the gold standard, but participants lacked the political will to “follow the rules of the game.” • The result for international trade and investment was profoundly detrimental. Bretton Woods System: 1945-1972 • Named for a 1944 meeting of 44 nations at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. • The purpose was to design a postwar international monetary system. • The goal was exchange rate stability without the gold standard. • The result was the creation of the IMF and the World Bank. Bretton Woods System: 1945-1972 British pound • • The U.S. dollar was pegged to gold at $35/ounce and other currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar. Each country was responsible for maintaining its exchange rate within +-1% of par value German mark French franc Par Value U.S. dollar Pegged at $35/oz. Gold Gold-exchange standard: U.S. dollar the only currency fully convertible to gold Collapse of the gold exchange standard • Professor Robert Triffin warned that the goldexchange system was programmed to collapse in the long run. • To satisfy the growing need for reserves, the United States had to run balance-of-payments deficits continuously, thereby supplying the dollar to the rest of the world. • But if the U.S. did just that, eventually the world will lose confidence in the dollar— Triffin Paradox • That indeed happened in the early 1970s. ▫ In August 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon announced the "temporary" suspension of the dollar's convertibility into gold The Flexible Exchange Rate Regime: 1973-Present • Flexible exchange rates were declared acceptable to the IMF members. ▫ Central banks were allowed to intervene in the exchange rate markets to resolve unwarranted volatilities. • Gold was abandoned as an international reserve asset. Current Exchange Rate Arrangements • No separate legal tender: • Currency of another country circulates as the sole legal tender (for example, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Panama). • Currency board: • An extreme form of the fixed exchange rate regime under which local currency is fully backed by a foreign currency at a fixed exchange rate leaving little room for discretionary monetary policy (for example, Hong Kong, Bulgaria, and Brunei). • Conventional peg: • Country formally pegs its currency at a fixed rate to another currency or basket of currencies (for example, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Nepal). • Stabilized arrangement: • Entails a spot market exchange rate that remains within a margin of 2% for 6 months or more (for example, Vietnam, Nigeria, and Lebanon). 1 3 Current Exchange Rate Arrangements • Crawling peg: • The currency is adjusted in small amounts at a fixed rate or in response to changes in selected indicators (for example, Honduras and Nicaragua). • Crawl–like arrangement: • Exchange rate must remain within a narrow margin of 2% relative to a statistically identified trend for 6 months or more, and the exchange rate cannot be considered floating (for example, Singapore, Romania, and Tunisia). • Pegged exchange rate with horizontal bands: • Value of the currency is maintained within certain margins of fluctuation of at least +/− 1% around a fixed central rate, or the margin between the maximum and minimum value of the exchange rate exceeds 2%. 1 4 Current Exchange Rate Arrangements 3 • Other managed arrangement: • Residual category used when the exchange rate arrangement does not meet the criteria for any of the other categories (for example, China, Argentina, and Kuwait). • Floating: • Exchange rate is largely market determined, without an ascertainable or predictable path for the rate (for example, Brazil, Korea, Turkey, India, South Africa, and Thailand). • Free floating: • Intervention occurs only exceptionally and aims to address disorderly market conditions; intervention has been limited to at most 3 instances in the previous 6 months, each lasting no more than 3 business days (for example, Australia, Canada, Mexico, Japan, U.K., U.S., and euro zone). 1 5 The Trade–Weighted Value of the U.S. Dollar since 1964 • The value of the U.S. dollar represents the nominal exchange rate index (2010 = 100) with weights derived from trade among 27 industrialized countries. • Source: Bank for International Settlements. 16 Value of the Euro in U.S. Dollars 1.5 1.4 1.3 1.2 1.1 1 0.9 0.8 1999 2000 2001 20022003200420052006200720082009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 China Renminbi’s Exchange Rate CHINESE RENMINBI TO US $ EXCHANGE RATE 8.5 8 7.5 7 6.5 6 5.5 ▫ China maintained a fixed exchange rate between the renminbi (RMB) yuan and the U.S. dollar for a long time. ▫ Beijing dropped an explicit peg to the US dollar in 2005 and switched to the current “managed floating exchange rate regime” ▫ The RMB floated between 2005 and 2008 and then again starting in 2010 ▫ The RMB has been included in the basket of currencies used by the IMF (reserve currency) in 2016. Currency crises: The Mexican Peso 1994 • On December 20, 1994, the Mexican government announced a plan to devalue the peso against the dollar by 14 percent. • This decision changed currency trader’s expectations about the future value of the peso, and they rushed for the exits. • International mutual funds had invested $45 billion in Mexican securities in the three years prior to the peso crisis • In their rush to get out, the peso fell by as much as 40 percent. Currency crises: The Mexican Peso 1994 • The Mexican Peso crisis is unique in that it represents the first serious international financial crisis touched off by cross-border flight of portfolio capital. ▫ As the world’s financial markets are becoming more integrated, contagious financial crisis are more likely to happen • Two lessons emerge: ▫ It is essential to have a multinational safety net in place to safeguard the world financial system from such crises. ▫ An influx of foreign capital can lead to an overvaluation in the first place. The Asian Currency Crisis: 1997 • The Asian currency crisis of 1997 turned out to be far more serious than the Mexican peso crisis in terms of the extent of the contagion and the severity of the resultant economic and social costs. • Many firms with foreign currency bonds were forced into bankruptcy. • The region experienced a deep, widespread recession. The Asian Currency Crisis Origins of the Asian Currency Crisis • As capital markets were opened, large inflows of private capital resulted in a credit boom in the Asian countries. ▫ The credit boom was often directed to speculation in real estate and stock markets • Fixed or stable exchange rates also encouraged unhedged financial transactions and excessive risk-taking by both borrowers and lenders. • The real exchange rate rose, which led to a slowdown in export growth. • Also, Japan’s recession (and yen depreciation) hurt. • As asset prices declined in part due to government’s effort to control overheated economy, the quality of bank loans also declined as the same assets were held as collateral The Asian Currency Crisis • If the Asian currencies had been allowed to depreciate in real terms (not possible due to the fixed exchange rates), the sudden and catastrophic changes in exchange rates observed in 1997 might have been avoided • Eventually something had to give—it was the Thai baht: ▫ The Thai central bank initially injected liquidity to the domestic financial system and tried to defend the exchange rate by using its foreign reserves ▫ With its foreign reserves declining rapidly, the central bank eventually decided to devalue the baht • The sudden collapse of the baht touched off a panicky flight of capital from other Asian countries. • The IMF came to rescue the three hardest-hit Asian countries: Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand. Lessons from the Asian Currency Crisis • Liberalization of financial markets when combined with a weak, underdeveloped domestic financial system tends to create an environment susceptible to currency and financial crisis • A fixed but adjustable exchange rate is problematic in the face of integrated international financial markets. ▫ A country can attain only two the of three conditions: 1. 2. 3. A fixed exchange rate. Free international flows of capital. Independent monetary policy. The Argentinean Peso Crisis: 2002 • In 1991 the Argentine government passed a convertibility law that linked the peso to the U.S. dollar at parity. • The initial economic effects were positive: ▫ Argentina’s chronic inflation was reduced. ▫ Foreign investment poured in. • As the U.S. dollar appreciated on the world market the Argentine peso became stronger as well. The Argentinean Peso Crisis: 2002 • However, the strong peso hurt exports from Argentina and caused a protracted economic downturn that led to the abandonment of peso– dollar parity in January 2002. ▫ The unemployment rate rose above 20 percent. ▫ The inflation rate reached a monthly rate of 20 percent. The Argentinean Peso Crisis: 2002 • There are at least three factors that are related to the collapse of the currency board arrangement and the ensuing economic crisis: ▫ Lack of fiscal discipline. ▫ Labor market inflexibility. ▫ Contagion from the financial crises in Brazil and Russia. • Competing claims on economic resources by different groups were accommodated by increasing public sector indebtedness • The government borrowed heavily in dollars, when the economy entered into recession, the government eventually defaulted on its internal and external debt: the largest sovereign default in history • 2018: back to the crisis The Argentinean Peso Crisis: 2018 • For years, governments printed money to finance wide budget deficits, causing consumer prices and inflation rate to spike • Economists had long argued that Argentina’s peso currency was overvalued • the peso plunged against the dollar in April, due to investor concerns about the government’s ability to control inflation and interest rate hikes by the U.S. Federal Reserve, which strengthened the dollar worldwide • The depreciation made Argentina’s dollar debts more expensive for the government, prompting it to turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a $50 billion loan. The Argentinean Peso Crisis: 2018 The Turkish Lira Crisis in 2018 • It looks like a classic emerging-market meltdown: • a rapidly growing economy funded by shortterm, dollar-denominated liabilities • In 2017 43% of total foreign direct investment flowed into Turkey's real estate sector • Turkish banks were heavily dependent on FX wholesale funding The Turkish Lira Crisis in 2018 Russian Ruble 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Currency Crisis Explanations • In theory, a currency’s value mirrors the fundamental strength of its underlying economy, relative to other economies, in the long run. • In the short run, currency trader expectations play a much more important role. • In today’s environment, traders and lenders, using the most modern communications, act on fight-or-flight instincts. For example, if they expect others are about to sell Brazilian reals for U.S. dollars, they want to “get to the exits first.” • Thus, fears of depreciation become self-fulfilling prophecies. Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes • Suppose the exchange rate is $1.40/€ today. • In the next slide, we see that demand for the euro far exceeds supply at this exchange rate (or the supply of U.S. dollars exceeds demand). • The United States experiences trade deficits. • Under a flexible exchange rate regime, the dollar will simply depreciate to $1.60/€, the price at which supply equals demand and the trade deficit disappears. Dollar price per € (exchange rate) Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes $1.60 $1.40 Supply (S) Dollar depreciates (flexible regime) Demand (D) Trade deficit QS QD = QS QD Q of € Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes • Instead, suppose the exchange rate is “fixed” at $1.40/€, and thus the imbalance between supply and demand cannot be eliminated by a price change. • The government would have to shift the demand curve from D to D*. ▫ In this example, this shift corresponds to contractionary monetary and fiscal policies. Dollar price per € (exchange rate) Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes Supply (S) Contractionary policies (fixed regime) $1.40 Demand (D) Demand (D*) QD* = QS Q of € Balance of Payments Accounts • The balance of payments accounts are those that record all transactions between the residents of a country and residents of all foreign nations. • They are composed of the following: ▫ The Current Account ▫ The Capital Account ▫ The Official Reserves Account ▫ Statistical Discrepancy The Current Account • Includes all imports and exports of goods and services. • If the debits exceed the credits, then a country is running a trade deficit. • If the credits exceed the debits, then a country is running a trade surplus. Balance of Payments Example • Suppose that Maplewood Bicycle in Maplewood, Missouri, USA imports $100,000 worth of bicycle frames from Mercian Bicycles in Darby, England. • There will exist a $100,000 credit recorded by Mercian that offsets a $100,000 debit at Maplewood’s bank account. • This will lead to a rise in the supply of dollars and the demand for British pounds. 341 The Capital Account • The capital account measures the difference between sales of assets to foreigners and purchases of foreign assets. • Sales of assets results in capital inflow; purchase of assets results in capital outflow • The capital account is composed of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), portfolio investments, and other investments. The Official Reserves Account • Official reserves assets include gold, foreign currencies, and reserve positions in the IMF. The Balance of Payments Identity BCA + BKA + BRA = 0 where BCA = balance on current account BKA = balance on capital account BRA = balance on the reserves account Under a pure flexible exchange rate regime, BCA + BKA = 0 Required reading • Eun C.S. and Resnik B.G. (2021) “International Financial Management”, Mc Graw Hill, Ch. 2 and Ch. 3 (read only)