FINANCIAL STATEMENTS,

DEPRECIATION, AND

CASH FLOW

III

Describe the purpose and basic components of the stockholders' report.

IIJ

Review the format and key components of the income statement and the balance sheet, and

interpret these statements.

II

Identify the purpose and basic content of the statement of retained earnings, the statement of

cash Rows, and the procedures for consolidating international financial statements.

III

Understand the effect of depreciation and other noncash charges on the firm's cash flows.

II

Determine the depreciable value of an asset, its depreciable life, and the amount of deprecia­

tion allowed each year for tax purposes using the modified accelerated cost recovery system

(MACRS) .

Analyze the firm's cash flows, and develop and interpret the statement of cash flows.

ACROSS tlte

DISCIPLINES

CHAPTER 3 IS IMPORTANT TO

• accounting personnel who calculate MACRS depreciation for tax

•

•

•

•

16

purposes and determine the best depreciation method for

tinancial reporting purposes.

information systems analysts who will design the financial infor­

mation system necessary to prepare the financial statements.

management, because it will maintain a dual focus on the com­

pany's cash Rows and profit and loss..

the marketing department, because its decisions will have signifi­

cant effects on the firm's cash flows and financial statements.

operations, whose actions will significantly impact the compa­

ny's cash Rows and profit and loss.

O

DAVID A. RANE

Vice President and Chief Financial Officer

Calloway Golf

Carlsbad, California

veryone in business , regardless of

position , needs to understand the

four key fi nancia l statements: the

income statement, balance sheet, statement

of reta ined earn ings, statement of cash

flows, and their footnotes. These statements

are the quickest woy to get a basic under­

sta nding of a company. Within genera lly

accepted accounting principles (GAAP),

compan ies have flexibility to choose meth­

ods and principles that best represen t the

operating resu lts and fin ancia l position of

the company. Therefore, the footnotes are

cri tica l to proper interpretation, provid ing

va luable information about the methods a

company uses to prepa re its fi nancia l state­

ments.

M ost compa nies use reports or models

other than basic fin ancia l statements, pre­

pa red at different levels of deta il and/or

focus, to manage their business. Ca lloway

G olf, a rapidly growing manufactu rer of

golf equipment, including Big Bertha golf

clubs, uses manageria l financia l reports

that include on ly the costs for wh ich a par­

ticular person is responsible. Our monthly

budgetary reports exclude depreciation or

overhead but include an interest charge fo r

use of capita l. Beca use these reports are

based on GAAP, our managers know how

the numbers were developed . So under­

stand ing basic fi nancia l statements gives

philosoph ies that reduce the amount of net

cash flow over the short term. For example,

Callaway has extended longer payment

terms to customers during the fall, our slow

season, so that they will purchase more

product, a nd lowered product prices to

increase market share-even though both

of these tactics may have a negative shortterm impact.

The statement of

cash flows is very valu­

able for management

and investors.

Measuring the sources

and uses of cash over

a given period pro­

The .four key

.financial

statements .

vides insight into how

are the quickest

well the company is

managing financ ially

way to get a basic

and identifies potential

problems. If you look at

C a llaway Golf's state­

ment of cash flows for

understanding of a

company.

1995 , you'd see that

we generated over

$95 mill ion positive cash flow from opera­

tions. This is important because, ultimately,

positive cash flow from operations pays the

bi lls.

you a head start wi th other fin ancia l

reports.

The ulti mate purpose of any business is

to generate cash flow over the long term.

This may req uire adoptin g management

David A. Rane, Vice President and Chief Rnancial Officer of

Calloway Golf, received his B.S. in Accounting. from Brigham

Young University.

77

78

PART 1

Introduction to Managerial Finance

II

generally accepted

accounting principles

(GAAPI

The practice and procedure guide­

lines used to prepare and main­

tain financial records and reports;

authorized by the Financial

Accounting Standards Board

(FASB).

Financial Accounting

Standards Board (FASBI

The accounting profession's rule­

setting body, which authorizes

generallyacceptedaccounting

principles (GAAP).

publicly held corpora­

tions

Corporations whose stock is

tradedon either an organized

securities exchange or the over­

the-counter exchange and/or

those with more than 55 million

in assets and 500 or more stock­

holders.

THE STOCKHOLDERS' REPORT

Every corporation has many and varied uses for the standardized records and

reports of its financial activities. Periodically, reports must be prepared for regu­

lators, creditors (lenders), owners, and management. Regulators, such as federal

and state securities commissions, enforce the proper and accurate disclosure of

corporate financial data. Creditors use financial data to evaluate the firm's abili­

ty to meet scheduled debt payments. Owners use corporate financial data to

assess the firm's financial condition and to decide whether to buy, sell, or hold its

stock. Management is concerned with regulatory compliance, satisfying creditors

and owners, and monitoring the firm's performance.

The guidelines used to prepare and maintain financial records and reports

are known as generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). These account­

ing practices and procedures are authorized by the accounting profession's rule­

setting body, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). Publicly held

corporations are those whose stock is traded on either an organized securities

exchange or the over-the-counter exchange and/or those with more than $5 mil­

lion in assets and 500 or more stockholders. ' These corporations are required by

the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC}-the federal regulatory body

that governs the sale and listing of securities-and by state securities commis­

sions to provide their stockholders with an annual stockholders' report. This

report, which summarizes and documents the firm's financial activities during

the past year, begins with a letter to the stockholders from the firm's president

and/or chairman of the board followed by the key financial statements . In addi ­

tion, other information about the firm is often included.

Securities and Exchange

Commission (SEC)

THE LETTER TO STOCKHOLDERS

The federa lregulatory body that

governs the sale and listing of

securities.

The letter to stockholders is the primary communication from management to

the firm 's owners. Typically, the first element of the annual stockholders' report,

it describes the events that are considered to have had the greatest impact on the

firm during the year. In addition, the letter generally discusses management phi­

losophy, strategies, and actions as well as plans for the coming year and their

anticipated effects on the firm's financial condition. Figure 3.1 includes the letter

to the stockholders of Intel Corporation, a major supplier (1995 sales of about

$16.2 billion) to the personal computing industry of chips, boards, systems, and

software that are the "ingredients" of the most popular computing architecture.

About 75 percent of the personal computers in use around the world today are

based on Intel-architecture microprocessors. The letter appears in Intel's 1995

annual stockholders' report. It discusses the firm's 1995 results, basic strategies,

business focus, competitive position, and challenges at the close of its fiscal yea r

ended December 30, 1995.

stockholders' report

Ann ual report required of publicly

held corporations that summa­

rizes and documents for stock­

holders the firm's fina ncial

activities during the past year.

letter to stockholders

Typically, the first element of the

annual stockholders' report and

the primary communication from

management to the firm's

owners.

'Although the Securities a nd Exchange Commission (SEC ) does nor have an official definition of

"publicly held, " thes e financial measures mark the cutoff point it uses to require informational

reporting, rega rdless of whether the firm publicl y sells its securities. Firms that do not meet these

requirements are commonly called "closely held" firms.

CHAPTER 3

FIGURE 3.1

Financia l Statements, Depreciation, and Cash Flow

Letter to Stockholders

Intel Corporation's 1995 letter to stockholders

to report our S·xt

ear of both record

Revenues totaled S16.2 billion, up 41 percent from $11.5 billion in

1994. Earnings per share rose 54 percent over last year, to S4.03.

Our strong performance in 1995 was rooted in growing demand

for PCs based on our Pentium' processors. The PC market continued its remarkable growth, with approximately 60 mi I! ion

PCs sold worldwide this year, up about 25 percent from 1994.

We were pleased to see the increased popularity of the Internet

and other communications applications this year. In particular, we

are very excited by the opportunities represented by the booming

World Wide Web. Witb more than 180 million units in use world·

wide, PCs are the predominant gate",ay to the World Wide Web.

We believe that this easy-ta-use, graphicaI!y based Internet interface will continue to attract new users and investments in the

PC communications world, helping to expand the PC's role as a

consumer communications device and driving future PC sales.

At Intel, our most important job is to make high-performance

microprocessors for the computing industry. To do this, we follow four basic strategies:

3. Remove barriers to technology flow. We believe

that if computers work better, do more and are easier to use,

more PCs will be sold and more Intel processors wiI! be needed.

We therefore work with other industry leaders to develop new

PC technologies, such as the PCl "bus;' which has been widely

adopted. This technology removes bottlenecks to provide greatly

enhanced graphics capabilities. We incorporate our chips into

PCI building blocks, such as PC motherboards, to help com­

puter manufacturers bring their products to market faster. We

also work closely with software developers to help create rich

applications, such as PC video conferencing and animated 3D

Web sites, that make the most of the power of Intel processors.

4. Promote the Intel brandw We continue to invest in

education and marketing programs that describe the benefits of

genuine Intel technology. Our Intel Inside* program expanded

in 1995 to include broadcast advertising. Hundreds of OEMs

worldwide are participating to let users know that there are

genuine Intel microprocessors inside their PCs.

New PC communications applications and emerging markets

1. Develop products quickly. We try to bring new tech­

nology to the market as quickly as possible. In 1995, we intro­

duced the new high-end Pentium" Pro processor. This came less

than three years after the introduction of the Pentium processor,

which is now the processor of choice in the mainstream PC

market. Together, these products provide computer buyers with

a wide spectrum of computing choices.

2. Invest in manufacturing. We believe Intel's state­

of-the·art chip manufacturing facilities are the best in the

industry. We spent 53.6 billion on capital in 1995, up 45 per­

cent from 1994. These heavy investments are paying off: in

1995, " 'e were able to bring our new 0.35-micron manufacturing

process into production months earlier than originally planned.

Our newest facility, the most advanced in the microprocessor

industry, makes our highest speed Pentium and Pentium Pro

processors. In the end, these investments benefit PC buyers

directly in the form of more powerful, less expensive com­

puting options.

Beyond our primary task of making microprocessors, we

invest in a range of computing and communications applications

that support our core business. Our supercomputer and network

server efforts take advantage of the flex.ibility and power of the

Intel architecture, whi le our f1asb memory business supports

booming communications applications such as cellular phones.

These product areas are detai led on the following pages.

Overall, our focused strategies have kept us on the right track.

Of course, we continue to attract competition, both from makers

of software-compatible microprocessors and from makers of

alternative-architecture ch.ips. We will try to stay nimble to

maintain our position in the industry.

This is a particularly exciting time to be in the computing

industry. New applications like the Internet are driving increased

demand for computers, and emerging markets around the world

are quickly adopting the latest computer technology. We look

forward to meeting the challenges of this business as the com­

puter's role continues to expand.

G OROOI'lo' E . M OORE

A N DR EW S. GROVE

CR AIG R . B AR RETT

Chairman

Presidenl and

Chief b ec:u[j\,c Officer

Exel;1Jli.."e Vicc Presidenl and

Chief Opcmting Officer

Source: Intel Corporation, 1995 Annual Report, p. 2. Reprinted by permission.

79

80

PART 1

Introduction to Managerial Finance

CPRACTICE

Picture Perfect

Don't underestimate the significance of a company's annual report to stock­

holders. In a study by Yankelovich Partners Inc., institutional and individual

investors ranked various sources of corporate information on a scale of 1 to 6.

Annual reports scored 4.7, second only to quarterly reports at 4.8. Well down

the list were news stories (4.2) and newsletters (3.3). Sixty-six percent of port­

folio managers and 54 percent of security analysts consider annual reports the

most important of all company documents.

T he presentation of the report also carries weight, contributing to the com­

pany's image with investors. You'll lose credibility if individual investors per­

ceive that the report is made of poor-quality materials; it's considered a sign

that company performance is declining. Leaving out pictures is another bad

move; 60 percent of respondents termed such reports as boring. •

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

Following the letter to stockholders will be, at minimum, the four key financial

statements required by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). These

statements are (1) the income statement, (2) the balance sheet, (3) the statement

of retained earnings, and (4) the statement of cash flows. 2 The annual corporate

report must contain these statements for at least the three most recent years of

operation (2 years for balance sheets). Following the financial statements are

N otes to Financial Statements-an important source of information on the

accounting policies, procedures, calculations, and transactions underlying entries

in the financial statements. H istorical summaries of key operating statistics and

ratios for the past 5 to 10 years are also commonly included with the financial

statements. (Financial ratios are discussed in Chapter 4.)

OTHER FEATURES

T he stockholders' reports of most widely held corporations also include discus­

sions of the firm's activities, new products, research and development, and the

like. M ost companies view the annual report not only as a requirement, but also

as an important vehicle for influencing owners' perceptions of the company and

its future o utlook. Because of the information it contains, the stockholders'

report may affect expected risk, return, stock price, and ultimately the viability

of the firm.

R e\'irw Qut'stions

3-1 W hat are generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)? Who autho­

rizes GAAP ? What role does the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

play in the financial reporting activities of corporations?

'Whereas these statement titles are consistently used throughout this text, it is important to recognize

that in practice, companies frequently use different statement titles. For example, General Electric

uses "Statement of Earnings" rather than "Income Statement" and "Statement of Financial Position"

rather th an " Bala nce Sheet"; Bristol Myers Squibb uses " Statement of Earnings and Retained

Earnings" rather than " Income Statement"; and Pfizer uses "Statement of Shareholders' Equity"

rather than "Statement of Retained Earnings. "

CHA PTER 3

Financial Statements, Depreciation, and Cash Flow

81

3-2 Describe the basic contents, including the key financial statements, of the

stockholders' reports of publicly held corporations.

II.

BASIC FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

Our chief concern in this section is to understand the factual information pre­

sented in the four required corporate financial statements. The financial state­

ments from the 1997 stockholders' report of a hypothetical firm, Baker

Corporation, are presented and briefly discussed in what follows. In addition,

the procedures for consolidating international financial statements are briefly

described.

INCOME STATEMENT

income statement

The income statement provides a financial summary of the firm's operating

Provides a financial summaryof

results during a specified period. M ost common are income statements covering

the firm's operating resultsduring a I-year period ending at a specified date, ordinarily December 31 of the calen­

a specified period.

dar year. (Many large firms, hmvever, operate on a 12-month financial cycle, or

fiscal year, that ends at a time other than December 31. ) Monthly statements are

typically prepared for use by management, and quarterly statements must be

made available to the stockholders of publicly held corporations.

Table 3.1 presents Baker Corporation's income statement for the year ended

December 31, 1997. The statement begins with sales revenue-the total dollar

amount of sales during the period-from which the cost of goods sold is de­

ducted. The resulting gross profits of $700,000 represent the amount remaining

to satisfy operating, financial, and tax costs after meeting the costs of producing

or purchasing the products sold. Next, operating expenses, which include selling

expense, general and administrative expense, and depreciation expense, are

deducted from gross profits. 3 The resulting operating profits of $370,000 repre­

sent the profits earned from producing and selling products; this amount does

not consider financial and tax costs. (Operating profit is often called earnings

before interest and taxes, or EBIT.) Next, the financial cost-interest expense­

is subtracted from operating profits to find net profits (or earnings) before taxes.

After subtracting $70,000 in 1997 interest, Baker Corporation had $300,000 of

net profits before taxes.

After the appropriate tax rates have been applied to before-tax profits, taxes

are calculated and deducted to determine net profits (or earnings) after taxes.

Baker Corporation's net profits after taxes for 1997 were $180,000. Next, any

preferred stock dividends must be subtracted from net profits after taxes to

arrive at earnings available for common stockholders. This is the amount earned

by the firm on behalf of the common stockholders during the period. Dividing

earnings available for common stockholders by the number of shares of common

stock outstanding results in earnings per share (EPS). EPS represents the amount

' Depreciation expense can be, and frequentl y is, included in manufacturing costs---cost of goods

sold-to calculate gross profits. Depreciation is shown as an expense in this text to isolate its impact

on cash flows.

82

PART 1

Introd uction to M anagerial Finance

,

TABLE 3.1

Baker Corporation Income Statement ($000) for the Year

Ended December 31, 1997

Sales revenue

$1 ,700

Less: Cost of goods sold

1,000

Gross profits

$ 700

Less; Operating expenses

Selling expense

General and administrati ve expense

Depreciation expense

$ 80

150

100

330

Total operating expense

Operating profits

$ 370

Less: Interest expense

70

Net profits before taxes

$ 300

Less; Taxes (ra te =40 % )

120

Less; Preferred srock dividends

$ 180

10

Earnings available for common stockholders

$ 170

Earnings per share (EPS)b

$ 1.70

Net profits after taxes

aInterest expense incl udes the interest compon ent of the annua l fin ancial lease payment as specified by the

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB ).

bCalcul ated by dividing the earnings available for common stockholders by t he number of shares of

common stock outsta nd ing ($ 170,000 .;.100,000 sha res = $1.70 per share) .

earned during the period on each outstanding share of common stock. In 1997,

Baker Corpora tion earned $1 70,000 for its common stockholders, which rep re­

sents $1.70 for each outstanding share. (The earnings per share amount rarely

equals the amount, if any, of common stock dividend s paid to shareholders.)

BALANCE SHEET

balance sheet

Summary statement of the firm!s

financial position at a given point

in time.

current assets

Short-term assets! expectedto be

converted intocash within 1year

or less.

current liabilities

Short-term liabilities! expectedto

be converted intocash within 1

year or less.

The balance sheet presents a summary statement of the firm's financial position

at a given point in time. T he statement balances the firm's assets (wha t it owns)

against its financing, wh ich can be either debt (what it owes ) or equity (what was

prov ided by owners). Baker Corpo ra tion 's bala nce sheets on Decem ber 31 of

1997 and 1996 are presented in Table 3.2. They show a variety of asset, liability

(debt ), and equity accounts. An important distinction is made between short­

term and long-term assets and liabil ities. The current assets and current liabilities

are short-term assets an d liabilities _T his means that t hey are expected to be con­

verted into cash within 1 year or less. All other assets and liabilities, along with

stockholders' equity, which is assumed to have an infinite life, are considered

long-term, or fixed, because they are expected to remain on the fi rm' s books for

1 year or more.

A few points about Baker Corporation's ba lance sheets need to be highlight­

ed. As is customary, the assets are listed beginning with the most liquid down to

CHAPTER 3

TABLE 3.2

83

Financial Statements, Depreciation, and Cash Flow

Baker Corporation Balance Sheets (SOOO)

December 31

Assets

1997

1996

$ 400

$ 300

Current assets

Cash

Marketable sec urities

600

200

Acco unts receiva ble

400

500

Inventories

Total current assets

600

900

$2,000

$1,900

$1,200

$1,050

Gross fixed assets (at cost)

Land and buildings

Machinery and equipment

850

800

Furniture and fixtures

300

220

Ve hicles

100

80

Other (includes certain leases )

50

50

---

$2,500

$2,200

1,300

1,200

$1,200

$1,000

$3,200

$2,900

$ 700

$ 500

Total gross fixed assets (at cost)

Less: Accumulated depreciation

et fixed assets

T ota I assets

Liabilities and stockholders ' equity

Current liabilities

Accounts payable

Notes payable

600

700

Accruals

100

200

Total current liabili ties

Long-term debt

Tota l liabilities

$1,400

$1,400

$ 600

$ 400

$2,000

$1,800

$ 100

$ 100

120

120

Stockholders' equ ity

Preferred stock

Common stock- $1.20 par, 100,000 shares outstanding

in 1997 and 1996

Paid-in capita l in excess of pa r on commo n stock

380

380

Retained earnings

600

500

$1,200

$1,100

$3,200

$2,900

Total stock holders' equity

Total liabilities and stockholders ' equity

the least liquid. Current assets therefore precede fixed assets. Marketable securi­

ties represent very liquid short-term investments, such as U.S. Treasury bills or

certificates of deposit, held by the firm. Because of their highly liquid nature,

84

PART 1

Introduction to Managerial Finance

par value

Per-share value arbitrarily

assignedto an issue of common

stock primarily for accounting

purposes.

paid-in capital in excess

of par

The amount of proceeds in excess

of the par value received from

the original sale of common

stock.

retained earnings

The cumulative total of all earn­

ings, net of dividends, that have

been retained and reinvestedin

the firm since its inception.

statement of retained

earnings

Reconciles the net income earned

during a given year, andany cash

dividends paid, with the change in

retained earnings between the

start and end of that year.

marketable securities are frequently viewed as a form of cash. Accounts receiv­

able represent the total monies owed the firm by its customers on credit sales

made to them. Inventories include raw materials, work in process (partially fin­

ished goods ), and finished goods held by the firm. The entry for gross fixed assets

is the original cost of all fixed (long-term) assets owned by the firm.4 Net fixed

assets represent the difference between gross fixed assets and accumulated depre­

ciation-the total expense recorded for the depreciation of fixed assets. (The net

value of fixed assets is called their book value.)

Like assets, the liabilities and equity accounts are listed on the balance sheet

from short-term to long-term. Current liabilities include accounts payable,

amounts owed for credit purchases by the ~i,m; notes payable, outstanding

short-term loans, typically from commercial banks; and accruals, amounts owed

for services for which a bill may not or will not be received. (Examples of accru­

als include taxes due the government and wages due employees.) Long-term debt

represents debt for which payment is not due in the current year. Stockholders'

equity represents the owners' claims on the firm. The preferred stock entry shows

the historic proceeds from the sale of preferred stock ($100,000 for Baker

Corporation) . Next, the amount paid in by the original purchasers of common

stock is shown by two entries--common stock and paid-in capital in excess of

par on common stock. The common stock entry is the par value of common

stock, an arbitrarily assigned per-share value used primarily for accounting pur­

poses. Paid-in capital in excess of par represents the amount of proceeds in

excess of the par val ue received from the original sale of common stock. The sum

of the common stock and paid-in capital accounts divided by the num ber of

shares outstanding represents the original price per share received by the firm on

a single issue of common stock. Baker Corporation therefore received $5.00 per

share [($120,000 par + $380,000 paid-in capital in excess of par) + 100,000

shares] from the sale of its common stock. Finally, retained earnings represent

the cumulative total of all earnings, net of dividends, that have been retained and

reinvested in the firm since its inception. It is important to recognize that retained

earnings are not cash but rather have been utilized to finance the firm's assets.

Baker Corporation's balance sheets in Table 3.2 show that the firm's total

assets increased from $2,900,000 in 1996 to $3,200,000 in 1997. The $300,000

increase was due primarily to the $200,000 increase in net fixed assets. The asset

increase in turn appears to have been financed primarily by an increase of

$200,000 in long-term debt. Better insight into these changes can be derived

from the statement of cash flows, which we will discuss shortly.

STATEMENT OF RETAINED EARNINGS

T he statement of retained earnings reconciles the net income earned during a

given year, and any cash dividends paid, with the change in retained earnings

between the start and end of that year. Table 3.3 presents this statement for

Baker Corporation for the year ended December 31, 1997. A review of the state­

ment shows that the company began the year with $500,000 in retained earnings

and had net profits after taxes of $180,000, from which it paid a total of

' For convenience the term fixe d assets is used throughout thi s text to refer to wh at, in a st rict

accounting sense, is captioned "property, plant, and equipment." This simplification of terminol ogy

permits certain financial concepts to be more easily devel oped.

CHAPTER 3

TABLE 3.3

8S

Financial Statements, Depreciation, and Cash Flow

Baker Corporation Statement of Retained Earnings 1$000) for

the Year Ended December 31/ 1997

Retained earnings balance (January 1, 1997)

$500

Plus: Net profits after taxes (for 1997)

180

Less: Cash dividends (paid during 1997)

Preferred srock

($10 )

Common stock

( 70 )

(80)

T otal di vidends paid

Retained earnings balance (December 31,1997)

$600

$80,000 in dividends, resulting in year-end retained earnings of $600,000. Thus,

the net increase for Baker Corporation was $100,000 ($180,000 net profits after

taxes minus $80,000 in dividends) during 1997.

STATEMENT OF {ASH FLOWS

statement of cash flows

Provides asummary of the firm's

operating, investment, and

financing cash flows and recon·

ciles them with changes in its cash

and marketable securities during

the period of concern.

The statement of cash flows provides a summary of the cash flows over the

period of concern, typically, the year just ended. The statement, which is some­

times called a "source and use statement," provides insight into the firm 's oper­

ating, investment, and financing cash flows and reconciles them with changes in

its cash and marketable securities during the period of concern. Baker

Corporation's statement of cash flows for the year ended December 31, 1997, is

presented in Table 3.10 on page 99. However, before we look at the preparation

of this statement, it is helpful to understand various aspects of depreciation.

CPRACTICE

What's Value Really Worth?

When Mitsubishi Motor Sales of America based its 1990 decision to acquire

Value Rent-A-Car on financial reports certified by Coopers & Lybrand, it

assumed that the statements presented Value's financial performance fairly.

Soon after, however, Mitsubishi dis covered that Value was worth negative $10

million, not the negative $5.9 million shown on its 1989 balance sheet.

Mitsubishi and Value's former owners settled their dispute, but in 1994,

Mitsubishi sued the Big Six accounting firm, charging that it allowed Value to

hide its poor financial condition. Mitsubishi said Coopers changed audit work

papers-long considered proof of an outside auditor's independence-a year

after the audit to protect against possible negligence charges. Mitsubishi

claimed it would not have purchased Value had it seen the revised work papers.

Coopers countered that only insignificant changes were made to the work

papers and that Mitsubishi should have focused instead on the audit report,

which questioned the rental company's value as a going concern . •

86

PART 1

Introduction to Ma nagerial Finance

CONSOLIDATING INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

Financial Accounting

Standards Board (FASB)

Standard No. 52

Ruling by FASB-the policy-set­

ting body of the U.S. accounting

profession-that mandates that

U.S.-based companies must trans­

late their foreign-currency­

denominated assets and liabilities

into dollars using the current rate

(translation) method.

current rate (translation)

method

Technique used by U.S.-based

companies to translate their for­

eign-currency-denominated assets

and liabilities into dollars (for

consolidation with the parent

company's fin ancial statements).

cumulative translation

adjustment

Equity reserve account on parent

company's books in which trans­

lation gains and losses ore accu­

mulated.

Example

So far, this chapter has discussed financia l statements involving only one curren­

cy, the U.S. dollar. How do we interpret the financial statements of companies

that have significant operations in other countries and cash flows denominated

in one or more foreign currencies? As it happens, the issue of how to handle con­

solidation of a company's foreign and domestic financial statements has bedev­

iled the accounting profession for many years, and the current policy is described

in Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB ) Standard No. 52. This ruling

by the policy-setting body of the accounting profession mandates that U.S.-based

companies must translate their foreign-currency-denominated assets and liabili­

ties into dollars (for consolidation with tl~ e parent company's financial state­

ments ) using a technique called the current rate (tr.ans lation) method.

Under the current rate (translation) method, all of a U.S. parent company's

foreign-currency-denominated ass ets and liabilities are converted into dollar

values using the exchange rate prevailing at the fiscal year ending date (the cur­

rent rate). Income statement items are treated similarly, although they can also

be translated by using an average exchange rate for the accounting period in

question. Equity accounts, on the other hand, are translated into dollars by using

the exchange rate that prevailed when the parent's equity investment was made

(the historical rate). Retained earnings are adjusted to reflect each year's operat­

ing profits or losses, but this account does not reflect gains or losses resulting

from currency movements. Instead, translation gains and losses are accumulated

in an equity reserve account on the parent company's books labeled cumulative

translation adjustment. Translation gains increase this account balance, and

tra nslation losses decrease it and can even result in a negative balance. H owever,

the gains and losses are not "realized " (run thro ugh the income statement and

consolidated to retained earnings) until the parent company sells or shuts down

its foreign subsidiary or its assets. Although international accounting rules and

managerial issues will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 20, an example can

be used to briefl y describe how translation gains and losses occur.

Suppose that an American company owns a subsidiary operating in Germany.

(The German currency is Deutsche marks, noted DM .) Suppose the subsidiary

has total assets worth DM 10,000,000, total liabilities of DM 5,000,000, and

DM 5,000,000 in equity. Suppose further that the exchange rate at the beginning

of the fiscal year was DM 2.00/U5$, which also equals the reciprocal of this,

US$.5 0IDM . Therefore, at the beginning of the period, the dollar value of the

subsidiary's assets, liab ilities, and equity is $5,000,000, $2,500 ,000, a nd

$2,500,000, respectively.

Now suppose that by the end of the fiscal year the German mark had depre­

ciated to a val ue o f DM 2.50/U5 $ , or US$ .40/D M. When the subsidiary's

accounts are then trans lated into dollars, the assets will have declined in va lue by

$1 ,000,000 to $4,000,000 (DM 10,000,000 x US$.40IDM). The subsidiary's lia­

bilities w ill also have declined in dollar valu e, but only by $500,000 to

$2,000,000 (DM 5,000,000 x US$.40IDM), and the dollar va lue of the equity

accounts remains unchanged at $2,500,000 . Because the parent company experi­

enced a decline in the dollar value of its foreign assets that exceeded the decline

in the dollar value of its li abilities, it has experienced a translation loss of

$500,000 ($1,000,000 decline in asset value minus $500,000 decline in the value

CHAPTER 3

Financial Statements, Depreciation, and Cash Flow

87

of liabilities). This $500,000 translation loss is recorded as a deficit in the parent

company's cumulative translation adjustment account.

R e\' iew Questions

3-3 What basic information is contained in: a. income statement; h. balance

sheet; and c. statement of retained earnings? Briefly describe each.

3-4 What role does Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Standard

No. 52 play in the consolidation of a company's foreign and domestic financial

statements? W hat is the current rate (translation) method and the cumulative

translation adjustment?

DEPRECIATION

11111

depreciation

The systematic charging of a por­

tion of the costs of fixed assets

against annual revenues over

time.

modified accelerated

cost recovery system

(MACRS)

System used to determine the

depreciation of assets for tax pur­

poses.

noncash charges

Expenses deducted on the income

statement that do not involve an

actual outlayof cash during the

period.

Business firms are permitted to systematically charge a portion of the costs of

fixed assets against annual revenues. This allocation of historic cost over time is

called depreciation. For tax purposes, the depreciation of business assets is regu­

lated by the Internal Revenue Code, which experienced major changes under the

Tax Reform Act of 1986. Because the objectives of financial reporting are some­

times different from those of tax legislation, a firm often will use different depre­

ciation methods for financial reporting than those required for tax purposes. (An

observer should therefore not jump to the conclusion that a company is attempt­

ing to "cook the books" simply because it keeps two different sets of records.)

Tax laws are used to accomplish economic goals such as providing incentives for

business investment in certain types of assets, whereas the objectives of financial

reporting are of course quite different.

Depreciation for tax purposes is determined by using the modified accelerated

cost recovery system (MACRS),s whereas for financial reporting purposes, a vari­

ety of depreciation methods are available. Before discussing the methods of depre­

ciating an asset, we must understand the relationship between depreciation and

cash flows, the depreciable value of an asset, and the depreciable life of an asset.

DEPRECIATION AND CASH FLOWS

The financial manager is concerned with cash flows rather than net profits as

reported on the income statement. To adjust the income statement to show cash

flow from operations, all noncash charges must be added back to the firm's net

profits after taxes. Noncash charges are expenses that are deducted on the income

statement but do not involve an actual outlay of cash during the period.

Depreciation, amortization, and depletion allowances are examples. Because

'This system, which was first established in 1981 with passage of the Economic Recovery Tax Act,

was initially called the "accelerated cost recovery system (ACRS)." As a result of modifications to

this system in the Tax Reform Act of 1986, it is now commonly called the "modified accelerated cost

recovery system (MACRS)." Although some people continue to refer to this system as " ACRS, " we

correctly call it "MACRS" throughout this text.

88

PART 1

Introduction to Managerial Finance

depreciation expenses are the most common noncash charges, we shall focus on

their treatment; amortization and depletion charges are treated in a similar fashion.

The general rule for adjusting net profits after taxes by adding back all non­

cash charges is expressed as follows:

Cash flow frolll operati()m = net pr()fits after taxes + noncash charges

(3 .1)

Applying Equation 3. 1 to the 1997, income statement for Baker Corporation

presented in Table 3.1 yields a cash flow from operations of $280,000 due to the

noncash nature of depreciation:

N et profits after taxes

Plus: Deprecia tion expense

Cash flo w fro m operations

$180,000

100,000

$280,000

(This value is only approximate, because not all sales are made for cash and not

all expenses are paid when they are incurred. )

Depreciation and other noncash charges shield the fi rm from taxes by lower­

ing taxa ble income. Some people do not define depreciation as a source of funds;

however, it is a source of funds in the sense that it represents a "nonuse" of funds.

Table 3.4 shows the Baker Corporation's income state~ent prepared on a cash

basis as an illustration of how depreciation shields income and acts as a nonu se of

funds. Ignoring depreciation, except in determining the firm's taxes, res ults in

cash flow fro m operations of $280,000-the value obtained before. Adjustment

of the firm's net profits after taxes by add ing back noncash charges such as depre­

ciation will be used on man y occasions in this text to estimate cash flo w.

TABLE 3.4

Baker Corporation Income Statement Calculated on a Cash

Basis ($000) for the Year Ended December 31 1 1997

Sales revenue

$1,700

Less: Cost of goods sold

1,000

Gross profits

$ 700

Less: Opera ting expenses

Selling expense

$ 80

General a nd administrative expense

150

Depreciation expense (no nca sh charge)

0

Total opera ting expense

230

Less: Interest expense

$ 470

70

Net profits before ta xes

$ 400

Operating profits

Less: Taxes (fro m T able 3.1 )

Cash flow from opera ti ons

120

$ 280

CHAPTER 3

Financial Statements, Depreciation , and Cash Flow

89

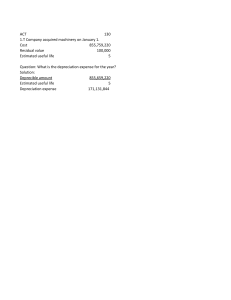

DEPRECIABLE VALUE OF AN ASSET

Under the basic MA CRS procedu res the depreciable value of an asset (the

amount to be depreciated) is its full cost, including outlays for installation. 6 N o

adjustment is required for expected salvage value.

Example

Baker Corporation acquired a new machine at a cost of $38,000, with installa­

tion costs of $2,000. Regardless of its expected salvage va lue, the depreciable

value of the machine is $40,000: $38,000 cost + $2,000 installation cost.

DEPRECIABLE LIFE OF AN ASSET

depreciable life

Time period over which an asset is

depreciated.

recovery period

The appropriate depreciable life

of a particular asset as deter­

mined by MACRS.

T he time period over which an asset is depreciated-its depreciable life-can sig­

nificantly affect the pattern of cash flows. The shorter the depreciable life, the

more quickly the cash flow created by the depreciation write-off will be received.

Given the financial manager's preference for faster receipt of cash flows, a short­

er depreciable life is preferred to a longer one. However, t!1e firm must abide by

certain Internal Revenue Service (IRS) req uirements for determining depreciable

life. T hese MACRS standards, which apply to both new and used assets, require

the taxpa yer to use as an asset's depreciable life the appropriate MACRS recov­

ery period, except in the case of certain assets depreciated under the alternative

depreciation system. 7 There are six MACRS recovery periods-3, 5, 7, 10, 15,

and 20 years-excludi ng real estate. As is cus tomary, the property classes

(excluding real estate) are referred to, in accordance with their recovery periods,

as 3-, 5-, 7-, 10-, 15-, and 20-year property. The first four property classes­

those routinely used by business- are defined in Table 3.5.

TABLE 3.5

Property class

(recovery period )

First Four Property Classes Under MACRS

Definition

3 years

Research and expe rimenr equ ipment and certain special tools.

5 yea rs

Co mputers, typewriters, copiers, duplicating equipment, cars,

light-duty trucks, qualified technologica l equipment, and simila r

assets.

7 yea rs

Office furniture, fixtures, most manufacturing equ ipment, railroad

track, and single-purpose agricul tu ral and horticu ltural struc­

tures .

10 years

Equipmenr used in petro leum refining or in the manufacture of

tobacco products and certain food products.

' Land va lues are not depreciable. Th erefore, to determine the depreciable va lue of real estate, the

value of the land is subtracted from the cost o f the real estate. In other words, only buildings and

other improvements are deprecia ble.

' For convenience, the deprec iation of assets under the alternative depreciation system is ignored in

this text.

90

PART 1

Introd uction to M anagerial Finance

CPRACTICE

Depreciation Counts When Buying a Car

If you understand how depreciation relates to car prices you can get a better

deal on your next car. The average new car depreciates 28 percent as soon as

you drive it away from the dealer. So, if you want a new car but can't afford the

model you love, consider buying it "nearly new" instead-12 to 24 months old.

With the increasing popularity of short-term car leases, you'll find a good

supply of well-maintained late-model used cars, and you won't pay for the high

depreciation in the early years.

Depreciation also plays a key role in the leasing process. When you lease a

car, the payment is based on the amount the car depreciates in the time covered

by the lease. To calculate your monthly lease payment, start with the cost of the

car (which you negotiate as you would for a straight cash purchase). Then sub­

tract the residual value, the estimated (depreciated) value of the car at the end

of the lease period, to get the depreciation . Your total lease payments will equal

the depreciation plus an interest factor. So with a higher residual value, you pay

for less depreciation. •

DEPRECIATION METHODS

For tax purposes, using MACRS recovery periods, assets in the first four proper­

ty classes are depreciated by the double-declining balance (200 percent) method

using the half-year convention and switching to straight-line when advantageous.

Although tables of depreciation percentages are not provided by law, the approx­

imate percentages (i.e., rounded to nearest whole percent) written off each year

for the first four property classes are given in Table 3.6. Rather than using the

percentages in the table the firm can either use straight-line depreciation over the

asset's recovery period with the half-year convention or use the alternative depre­

ciation system. For purposes of this text we will use the MACRS depreciation

percentages given in Table 3.6, because they generally provide for the fastest

write-off and therefore the best cash flow effects for the profitable firm.

Because MACRS requires use of the half-year convention, assets are assumed

to be acquired in the middle of the year, and therefore only one-half of the first

year's depreciation is recovered in the first year. As a result, the final half-year of

depreciation is recovered in the year immediately following the asset's stated

recovery period. In Table 3.6, the depreciation percentages for an n-year class

asset are given for n + 1 years. For example, a 5-year asset is depreciated over 6

recovery years. (Note: The percentages in Table 3.6 have been rounded to the

nearest whole percentage to simplify calculations while retaining realism.)

For financial reporting purposes a variety of depreciation methods-straight­

line, double-declining balance, and sum-of-the-years'-digits S-can be used.

Because primary concern in managerial finance centers on cash flows, only tax

depreciation methods will be utilized throughout this textbook. The application

of the tax depreciation percentages given in Table 3.6 can be demonstrated by a

simple example.

' For a review of these depreciation methods as well as other aspects of financial reporting, see any

recently published financial accounting text.

CHAPTER 3

TABLE 3.6

91

Fi nancial Statements, Depreciation, and Cash Flow

Rounded Depreciation Percentages by Recovery Year Using

MACRS for First Four Property Classes

Percentage by recovery year"

Recovery year

3 years

5 years

7 years

10 years

1

33%

20%

14%

10%

2

45

32

25

18

3

4

15

7

19

18

14

12

12

12

5

12

9

9

6

7

5

9

8

7

9

8

4

6

9

6

10

6

4

11

Totals

100%

100%

100%

100%

"These percentages have been rounded to the nearest whole percent to simplify calculations while retaining

rea lism. To calculate the actual depreciation for tax purposes, be sure to apply the actual unrounded per­

centages or directly apply double-declining balance (200 %) depreciation using the half-year convention.

Example

Baker Corporation acquired, for an installed cost of $40,000, a machine having

a recovery period of 5 years. By using the applicable percentages from Table 3.6,

the depreciation in each year is calculated as follows:

Year

Cost

(1)

Percentages

(from Table 3.6)

(2)

Depreciation

[(1) x (2)]

(3)

$40,000

20%

$ 8,000

2

40,000

32

12,800

3

4

40,000

19

7,600

40,000

12

4,800

5

40,000

12

4,800

6

40,000

5

2,000

100%

$40,000

Totals

Column 3 shows that the full cost of the asset is written off over 6 recovery

years.

92

PA RT 1

Introduction to Managerial Finance

I n · iew Questions

3-5 In what sense does depreciation act as cash inflow? How can a firm's after­

tax profits be adjusted to determine cash (low from operations?

3-6 Briefly describe the first four modified acce lerated cost recovery system

(MACRS) property classes and recovery periods. Explain how the depreciation

percentages are determined by using the MACRS recovery periods.

ANALYZING THE FIRM'S CASH FLOW

II

The statement of cash (lows, briefly described earlier, summarizes the firm's cash

flow over a given period of time. Because it can be used to capture histo ric cash

flow, the statement is developed in this section. First, however, we need to dis­

cuss cash flow through the fi rm and the classification of sources and uses.

THE FIRM'S CASH FLOWS

operating flows

Cash flowsdirectly related to pro­

duction and sale of the firm 's

products and services.

investment flows

Cash flows associated with pur­

chase and sale of both fixed

assets and business interests.

financing flows

Cashflows that result from debt

and equity financing transactions;

includes incurrence and repay­

ment of debt, cash inflowfrom

the sale of stock, andcash out­

flows to repurchase stock or pay

cash dividends.

Figure 3.2 illustrates the firm 's cash flows. N ote th at both cash and marketable

securities, which, because of their highly liquid nature, are considered the same

as cas h, represent a reservoir of liquidity th at is increased by cash inflows and

decreased by cash outflows. Also note tha t the firm's cash flo ws have been d ivid­

ed into (1) operating flows, (2) investment flows, and (3) financing fl ows. The

operating flows are cash flows- inflows and outflows-directly related to pro­

duction and sale of the firm's products and services. These flows capture the

income statement and current account transactions (excl uding notes paya ble)

occurring during the period. Investment flows are cash flows associated with

purchase and sale of both fixed assets and business interests. Clearly, purchase

transactio ns would resu lt in cash ou tflo ws, whereas sales transactions would

generate cash inflows. The financing flows result from debt and equity financing

tra nsacti ons. Incurring and repaying either short-term debt (notes payable) or

long-term debt would resu lt in a correspond ing cash inflow or outflow .

Similarly, the sale of stock wo uld result in a cash inflow, whereas the repurchase

of stock or payment of cash dividends would result in a financing outflow. In

combination, the fi rm's operating, investment, and financing cash flows during a

given period will increase, decrease, or leave unchanged the firm's cash and mar­

ketable securities balances.

CLASSIFYING SOURCES AND USES OF CASH

The statement of cash flows in effect summarizes the sources and uses of cash

during a given period . (Table 3.7 on page 94 classifies the basic sources and uses

of cash. ) For example, if a firm's accounts payable increased by $1,000 during

the year, this change would be a source of cash. If the firm's inventory increased

CHA PTER 3

FIGURE 3.2

93

Fi nan cial Sta te me nts, Depreciation, a nd Cash Flow

Cash Flows

The firm's cash flows

(1 ) Operating Flows

(2) Investment Flows

,------------------------------------,------------------------------------­I

.....

Accrued

Wages

~.. ..

labor

Payment af Accruals

~.........................~

Payment ~

of Credit

j'urchases ~

1

Raw

~.... Accounts

Payable ................ : :

Materials .....

~ ~

Depreciation

I .........

Purchase

!........................................................

~.~!~...... .......................

F" ed A

ssets

IX

1 :

:

~

Work in

Process

Overhead

Expenses

~..··..

Business

Interests

' ::

:.1::

,""ho~

Fi nished

Goods

i

• • •• ••••••• •• ••••• ••••• ••••• •• • •••• ••••• ••••• •• •• ••• •• ••••••• 1

Sale

.................................................................

,~

~

O perating (incl.

Depreciation) and

Interest Expense

--------------------------------~

~....... ;

Cash

~............................................... Ma~:~able

(3) Financing Flows

Securities

Borrowing

..............................................

Repayment

..............................................

~

...............................................

..................................................

~

Taxes

t

Sales

Payment

~

· · : I ~:~: "·~ · · · ·J 1

~ .

: :

l l....................................................

:

~

Sale of Stock

Repurchase of Stock

...................................................

..

Payment of Cash Dividends

,....................................................... .

~

Accounts

Rece ivable

Debt

(Short-Term and

long-Term)

:

Equity

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I ____________________________________ J• ____________________________________ _I

........................................................... ,

by $2,500, the change would be a use of cash, meaning that an additional $2,500

was tied up in inventory.

A few additional points shou ld be made with respect to the classification

scheme in Ta ble 3.7:

1. A decrease in an asset, such as the firm's cash balance, is a source of cash

flow because cash that has been tied up in the asset is released and can be

used for some other purpose , such as repaying a loan. O n the other hand, an

94

PART 1

Introduction to Managerial Fi nance

TABLE 3.7

The Sources and Uses of Cash

Sources

Uses

Decrease in any asset

Increase in any lia bility

Decrease in any liability

Increase in any asset

Net profits after taxes

Net loss

Depreciation and other noncash charges

Dividends paid

Sale of stock

Repurchase or retirement of stock

increase in the firm's cash balance is a use of cash flow, because additional

cash is being tied up in the firm's cash balance.

2. Earlier, Equation 3.1 and the related discussion explained why depreciation

and other noncash charges are considered cash inflows, or sources of cash.

Adding noncash charges back to the firm's net profits after taxes gives cash

flow from operations:

Cash flow from operat ions = net profits after taxes + noncas h charge s

Note that a firm can have a net loss (negative net profits after taxes) and still

have positive cash flo w from operations when noncash charges (typically

depreciation) during the period are greater than the net loss. In the statement

of cash flows, net profits after taxes (or net losses) and noncash charges are

therefore treated as separate entries.

3. Because depreciation is treated as a separate source of cash, only gross rather

than net changes in fixed assets appear on the statement of cash flows. This

treatment avoids the potential double counting of depreciation.

4. Direct entries of changes in retained earnings are not included on the state­

ment of cash flows. Instead, entries for items that affect retained earnings

appear as net profits or losses after taxes and dividends paid.

DEVELOPING THE STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS

The statement of cash flows can be developed in five steps: (1,2, and 3) prepare

a statement of sources and uses of cash, (4) obtain needed income statement

data, and (5 ) properly classify and present relevant data from Steps 1 through 4.

With this five-step procedure we can use th e financial statements for Baker

Corporation presented in Tables 3.1 and 3.2 to demonstrate the preparation of

its December 31, 1997, statement of cash flows.

PREPARING THE STATEMENT OF SOURCES AND U SES OF :::ASH (STEPS 1, 2,

AND 3)

The first three steps in the statement of cash flow preparation process guide the

preparation of the statement of sources and uses of cash.

Step 1 Calculate the balance sheet changes in assets, liabilities, and stockhold­

ers' equity over the period of concern. (N ote: Calculate the gross fixed

CHA PTER 3

Fi nancial Statements, Depreciation, and Cash Flow

95

asset change for the fixed asset account along with any change in accu­

mulated depreciation.)

Step 2 Using the classification scheme in Ta ble 3.7, classify each change calcu­

lated in Step 1 as either a source (S) or a use (U). (N ote: An increase in

accumulated depreciation would be classified as a source, whereas a

decrease in accumulated depreciation would be a use. Changes in stock­

holders' equity accounts are classified in t he same way as changes in lia­

bilities-increases are sources, and decreases are uses.)

Step 3 Separately sum all sources and all uses found in Steps 1 and 2. If this

statement is prepared correctly, total sources should equal total uses.

Example

Baker Corporation's balance sheets in Table 3.2 can be used to develop its state­

ment of sources and uses of cash for the year ended December 31, 1997.

Step 1 The key entries from Baker Corporation's balance sheets in Table 3.2

are listed in a stacked format in Table 3.8. Column 1 lists the account

name, and columns 2 and 3 give the December 3 1, 1997 and 1996

values, respectively, fo r each account. In column 4, the change in the

balance sheet account between December 31, 1996, and December 31,

1997, is calculated. N ote that for fixed assets, both the gross fi xed asset

change of +$300,000 and the accum ulate d depreciat io n change of

+$100,000 are calculated.

Step 2

Based on the classification scheme from Table 3.7 and recognizing that

changes in stockholders' equity are classified in the same way as changes

in liabilities, each change in colu mn 4 of Ta ble 3.8 is classified as either a

source in column 5 or a use in col umn 6.

Step 3 The sources and uses in columns 5 and 6, respectively, of Table 3.8 are

totaled at the bottom. Because total sources of $1,000,000 equal total

uses of $1,000,000, it appears that the statement has been correctly pre­

pared.

OBTAINING INCOME STATEMENT D ATA (STEP 4)

Step 4 involves obtaining three important inputs to the statement of cash flows

from an income statement for the period of concern. These inputs are (1) net

profits after taxes, (2) depreciation and any other noncash charges, and (3) cash

dividends paid on both preferred and common stock.

Step 4

Net profits after taxes and depreciation typically can be taken directly

from the income statement. Dividends may have to be calculated by

using the following equation:

Dividends = net profits after taxes - change in retained earnings

(3 .2 )

PART 1

96

TABLE 3.8

Introduction to M anagerial Finance

Baker Corporation Statement of Sources and Uses of Cash ($000) for the Year Ended

December 31, 1997

Account balance

December 31

(from Table 3.2)

Change

Classification

(1)

1997

(2)

1996

(3)

[(2) - (3)]

(4)

Assets

Cash

$ 400

$ 300

+$100

200

Accounts receiva ble

600

400

500

+ 400

- 100

$ 100

Inventories

600

900

- 300

300

2,500

2,200

+ 300

1,300

1,200

+ 100

100

Accounts payable

700

600

500

700

+ 200

- 100

200

Notes payable

Accruals

100

200

- 100

Long-term debt

600

400

+ 200

100

100

120

120

Account

Marketable securities

Gross fixed assets

Accumulated depreciation

a

Source

Use

(5)

(6)

$ 100

400

300

Liabilities

100

100

200

Stockholders' equity

Paid-in capital in excess of par

380

380

a

a

a

Retained earnings

600

500

+ 100

100

Totals

$1,000

Preferred stock

Common stock at par

aBecause accum ulated depreciation is treated as a deduction from gross fixed assers , a n increase in it is classified as a sou rce; any decrease would

be c1assi fied as a use.

The value of net profits after taxes can be obtained from the income

statement, and the change in retained earnings can be found in the state­

ment of sources and uses of cash or can be calculated by using the begin­

ni!1g- and end-of-period balance sheets. T he dividend value could be

obtained directiy from the statement of retained earnings, if available.

Example

Baker Corporation's net profits after taxes, depreciation, and dividends can be

found in its financial statements.

Step 4

Baker Corporation's net profits after taxes and depreciation for 1997

can be found on its income statement presented in Table 3.1:

Net profits after taxes ($000)

Depreciation ($000)

$180

$100

CHA PTER 3

Financial Statements, Depreciction, and Cash Flow

97

Substitu ting the net profits after taxes value of $1 80,000 and th e

increase in retained earnings of $1 00,000 from Baker Corporation's

statement of sources and uses of cash for the year ended December 31,

1997, given in Table 3.8, into Equation 3.2, we find the 1997 cash divi­

dends to be

Dividends ($000) = $180 - $100 = $80

Note that the $80,000 of dividends just calculated could have been drawn

directly from Baker's statement of retained earnings, given in Table 3.3.

CLASSIFYING AND PRESENTING RELEVANT D ATA (STEP 5)

The relevant data from the statement of sources and uses of cash (prepared in

Steps 1, 2, and 3) along with the net profit, depreciation, and dividend data

(obtained in Step 4) from the income statement can be used to prepare the state­

ment of cash flows.

Step 5

Classify relevant data into one of three categories:

1. Cash flow from operating activities

2. Cash flow from investment activities

3. Cash flow from financing activities

These three categories are consistent with the operating, investment, and

financing cash flows depicted in Figure 3.2. Table 3.9 lists the items that

TABLE 3.9

Categories and Sources of Data Included in the Statement of

Cash Flows

Data source

Categories and data items

S/U =Statement of sources

and uses of cash

IJS =Income statement

Cash Flow from Operating Activities

Net profits (losses) after taxes

Depreciation and other noncash charges

Changes in all current assets other than cash and

marketa ble securities

Cha nges in all current liabilities other than notes pa ya ble

IIS

IIS

SfU

SfU

Cash Flow from Investment Activities

Changes in gross fixed assets

Changes in business interests

SfU

SfU

Cash Flow from Financing Activities

Changes in long-term debt

SfU

SfU

Changes in stockholders' equity other than retained

earnings

SfU

Dividends paid

IIS

Changes in notes payable

98

PART 1

Introduction to Ma nagerial Finance

would be included in each category on the statement of cash flows . In

addition the source of each data item is noted. By reviewing Ta ble 3.9, it

can be seen that all current asset changes other than cash and mar­

ketable securities and all current liab ility changes other than accounts

payable are included under "Cash Flow from Operating Activities." The

cash and marketable securities changes are excluded because they repre­

sent the period's net cash flow to which the statement is reconciled.

N otes payable are included in "Cash Flow from Financing Activities"

because they reflect deliberate financing actions rather than the sponta­

neous financing that resu lts from o t her current liabil ities such as

accounts payable and accruals.

Relevant data shou ld be listed in a fa shion consistent with the order

of the categories and data items given in Tab le 3.9. All sources as well as

net profits after taxes and depreciation would be treated as positive

values-cash inflows-whereas all uses, any losses, and dividends paid

would be treated as negative va lues-cash outfl ows. The items in each

category-operating, investment, and fina ncing-should be totaled, and

these three totals should be added to get the "net increase (decrease) in

cash and marketable securities" for the period. As a check, this value

should reconcile with the actual change in cash and marketa ble securi­

ties for the year, which can be obtained from either the beginning- and

end-oF-period ba la nce sheets or the statement of so urces and uses of cash

for the period.

Example

T he relevant data developed for Baker Corporation for 1997 can be combined by

using the proced ure described before to create its statement of cash flows.

Step 5

Classifying and listing the relevant data from earlier steps in a fashion

consistent with Ta ble 3 .9 result in Baker Corporation's Statement of

Cash Flows, presented in Table 3. 10. On the basis of this statement, the

firm experienced a $500,000 increase in cash and marketable securities

duri ng 1997. Looking at Baker Corporation's Decem ber 31, 1996 and

1997 balance sheets in Ta ble 3.2 or its sta tement of sources and uses of

cash in Tab le 3.8, we can see that the fir m' s cash increased by $1 00,000

and its marketa ble securities increased by $400,000 between December

31, 1996, and December 31, 1997. The $500,000 net increase in cash

and marketable securities from the statement of cash flows therefore rec­

onciles with the total change of $5 00,000 in these accounts during 1997.

The statement is therefore believed to have been correctly prepared.

INTERPRETING THE STATEMENT

The statement of cash flows allows the financia l manager and other interested

parties to analyze the firm's past and possibly future cash fl ow. The manager

should pay special attention to both the major categories of cash flow and the

individual items of cash inflow and outflow to assess w hether any developments

have occurred that are contrary to the company's financial po licies. In addition,

the statement ca n be used to evaluate the fu lfill ment of projected goals . Specific

links between cash infl ows and outflows cannot be made by using this statement,

but the statement can be used to isolate inefficiencies. For example, increases in

CHAPTER 3

TABLE 3.10

Fina ncial Statements, Depreciation, and Cash Flow

99

Baker Corporation Statement of Cash Flows 1$000) for the

Year Ended December 31, 1997

Cash Flow from Operating Activities

Increase in acco unts payable

$180

100

100

300

200

Decrease in accruals

(100 )a

Net profits after taxes

Deprecia tion

Decrease in accounts rece iva ble

Decrease in inventories

$780

Cash provi ded by operating activities

Cash Flow from Investmen t Activities

Increase in gross fixed assets

($300)

Changes in business interests

o

(3 00 )

Cash provided by in vestment activi ties

Cash Flow from Financing Activities

Decrease in notes payable

Increase in long-term debts

Changes in stockho lders' equi tyb

Dividends pa id

Cash provided by financing activities

Net increase in cash and marketable securities

($1 00 )

200

o

~

20

$500

aAs is customa ry, parentheses arc used to denote a negative number, which in this case is a cash outflow.

bConsistent with this data item in Table 3.9, retained earn ings are excluded here, because their change is

actually reflected in the combination of the net profi ts after taxes and dividend entries.

accounts receivable and invento ries resulting in major cash outflows ma y signal

cred it or inventory problems, respectively.

In addition, the financia l manager can prepa re and analyze a statement of

cash flo ws developed fro m projected, or pro forma, financial statements. This

approach can be used to determine whether planned actions are desirable in view

of the res ulting cash flows.

Example

Analysis of Baker Corporation'S statement of cash flows in T able 3.10 does not

seem to indicate the existence of any majo r problems for the company. Its

$780,000 of cash provided by operating activities plus the $20,000 provided by

fi na ncing activities were used to invest an additional $300,000 in fixed assets

and to increase cash and marketable securities by $500,000. The individual items

of cash inflow and outflow seem to be distributed in a fashion consistent with

prudent financial management. The firm seems to be growing, because (1) less

than half of its earnings ($ 80,000 out of $ 180,000) was paid to owners as divi­

dends and (2) gross fixed assets increased by three times the amount of historic

cost written off through depreciation expense ($300,000 increase in gross fixed

100

PART 1

Introduction to Manageria l Fi nance

assets versus $1 00,000 in depreciation expense). M aj or cash inflows were real­

ized by decreasing inventories and increasing accounts payable. The major,)Ut­

flow of cash was to increase cash and marketable securities by $500,000 and

thereby improve liquidity. Other inflows and outflows of Baker Corporation

tend to support the fact that the firm was well managed financially during the

period. An understanding of the basic financial principles presented throughout

this text is a prerequisite to the effective interpretation of the statement of cash

{lows.

R eliew Questions

3-7 Describe the overall cash flow through the fi rm in terms of: a. operating

flows; b. investment flows; and c. financing flows.

3-8 List and describe sources of cash and uses of cash. Discuss why a decrease

in cash is a source and an increase in cash is a use.

3-9 Describe the procedure (the first three steps for developing the statement

of cash flows) used to prepare the statement of sources and uses of cash. How

are changes in fixed assets and accumulated depreciation treated on this state­

ment?

3-10 What three inputs to the statement of cash flows are typically obtained (in

Step 4) from an income statement for the period of concern? Explain how the

income statement and statement of sources and uses of cash can be used to deter­

mine dividends for the period of concern. What other methods can be used to

obtain the value of dividends?

3 -11 Describe the general format of the statement of cash fl ows. W hy are

cash and marketable securities the only current assets and notes payable the

only current liability excluded from the "Cash Flow from Operating

Activities" ?

3-12 Review the final step (Step 5) involved in preparing the statement of cash

flows. How can the accuracy of the final statement balance, "net increase

(decrease) in cash and marketable securities," be conveniently verified?

3-13 How is the statement of cash flows interpreted and used by the financial

manager and other interested parties?

SUMMARY

III

Describe the purpose and basic components

of the stockholders' report. The annual stock­

holders' report, which publicly traded corporations

are required to provide to their stockholders, sum­

marizes and documents the firm's financial activi­

ties during the past year. It includes, in addition to